-

Podcast - How much is Greece getting out of the RRF?

Podcast - How much is Greece getting out of the RRF?

-

Podcast - Between investment grade and rule of law: Greece's contrasting images

Podcast - Between investment grade and rule of law: Greece's contrasting images

-

Where is Greek growth coming from?

Where is Greek growth coming from?

-

Bravo, Bank of Greece

Bravo, Bank of Greece

-

Podcast - A year on from Tempe train crash, trust fades as questions mount

Podcast - A year on from Tempe train crash, trust fades as questions mount

-

Podcast - SYRIZA embraces the chaos

Podcast - SYRIZA embraces the chaos

What in the world will we do without barbarians?

Just as the five-year anniversary of Greece’s first EU/IMF programme approaches - and despite marked procrastination in a number of other fronts - Greece’s coalition set up a parliamentary committee to investigate the country’s bankruptcy and the signing of its two memorandums with the troika.

Paradoxically, the committee will investigate the period from October 2009, which is effectively the phase when the country’s insolvency was managed rather than created. This adds to the plethora of indications to date that the country’s political personnel refuses to face reality. It also raises serious issues about the capacity of the same people to take Greece out of the economic and social catastrophe the last five years have brought.

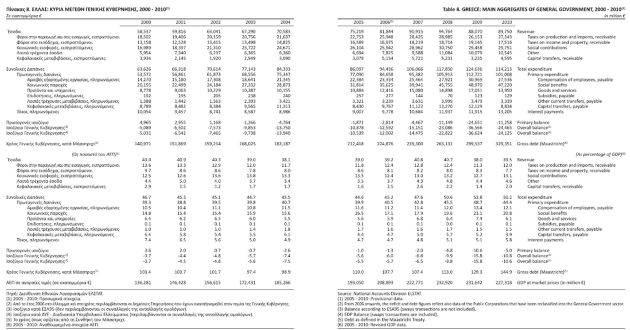

A good starting point for the committee would be a regular publication of the Hellenic Statistics Authority, which contains extensive macro, and fiscal data of the Greek economy, including this table with the main aggregates of the general government accounts since 2000.

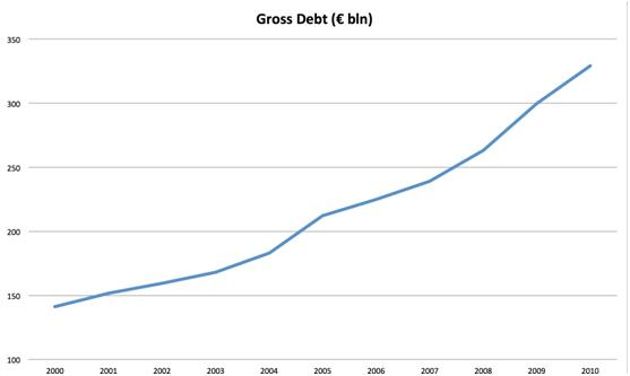

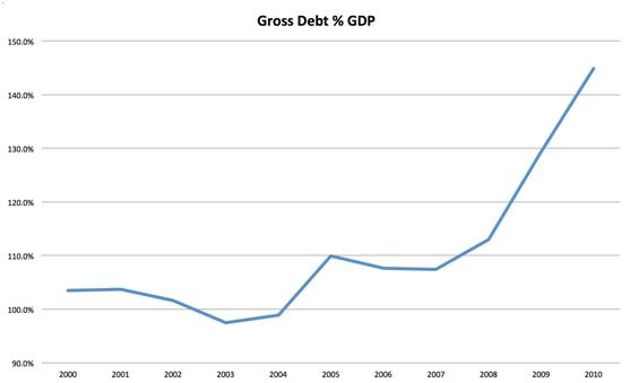

Greece entered the new millennium and the euro era with a debt of circa 141 billion euros, or just over 103 percent of its economy. To service that debt Greece needed about 10 billion euros per year, which in 2000 and 2001 represented approximately 7 percent of GDP.

With the effective interest rate - interest payments over the stock of debt – at just under 7 percent, the equation of the debt dynamics was pretty straightforward: Unless Greece was growing at phenomenal speeds and running consistent primary surpluses, it would soon find itself in trouble.

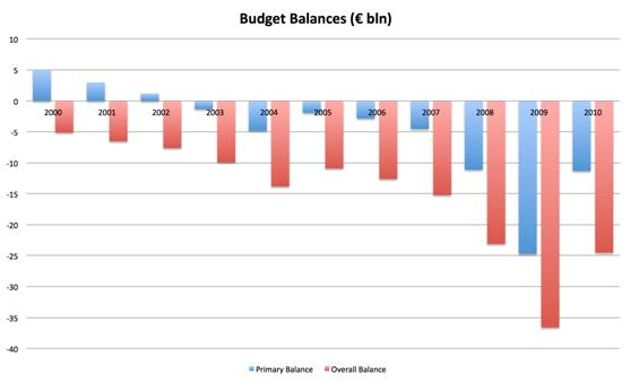

Greece’s political class soon started wasting the opportunities they were presented with. Greece became one of the fastest growing economies in the eurozone and membership of the single currency created the kind of euphoria that allowed Greece to start borrowing at a cost comparable to Germany, which brought total interest payments to 8.6 billion euros in 2003. In that year the primary surpluses of the previous three years disappeared and the overall budget deficit shot up to 5.7 percent of GDP.

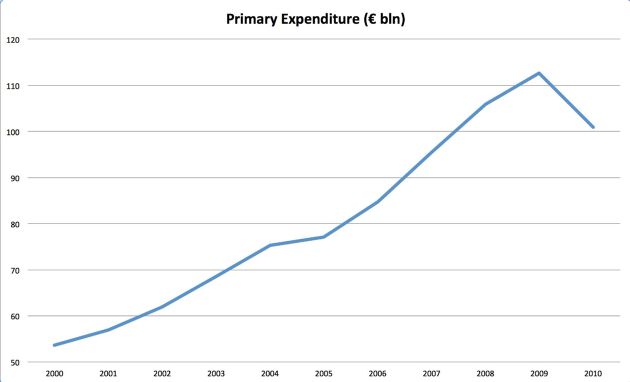

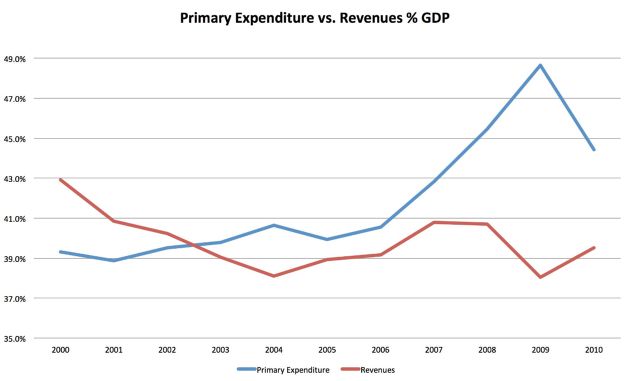

Primary expenditure – spending before interest payments – rose rapidly throughout the decade, doubling from circa 53 billion euros in 2000 to 113 billion euros in 2009.

Expenses before interest payments went from just over 39 percent of GDP to 49 percent in 2009, while revenues failed to keep up in spite of the economic boom.

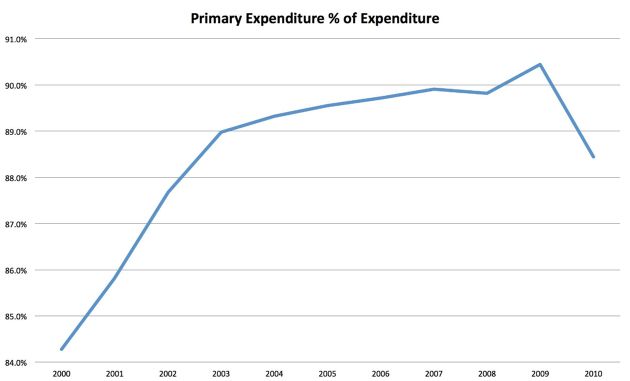

Aggravating Greece’s fiscal position, primary expenditure edged up to 89 percent in the early years of euro adoption and exceeded 90 percent of total expenditure by 2009.

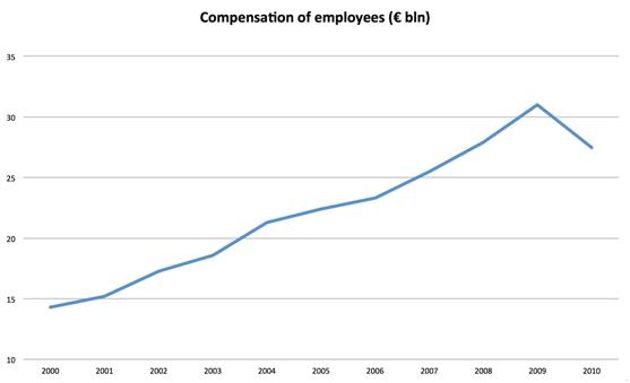

When Greece entered the euro it had a wage bill below 15 billion euros. By 2009 this figure had doubled.

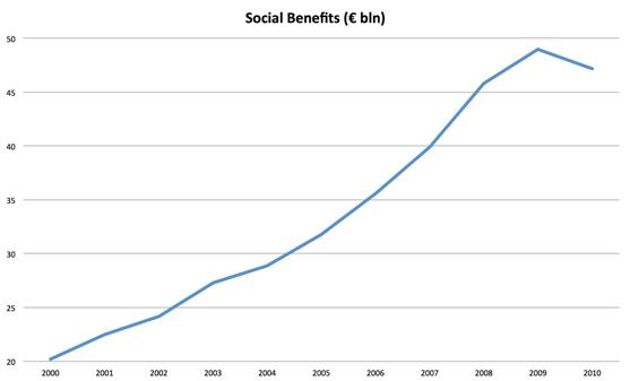

The social benefits bill shot up from 20 billion euros in 2000 to 49 billion in 2009.

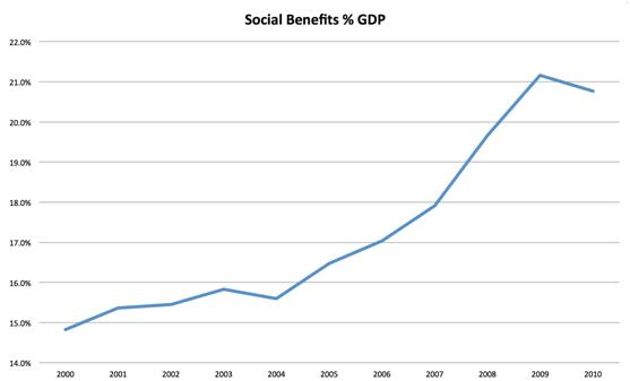

This increase meant that social benefits represented more than 21 percent of GDP by 2009 from less than 15 percent in 2000.

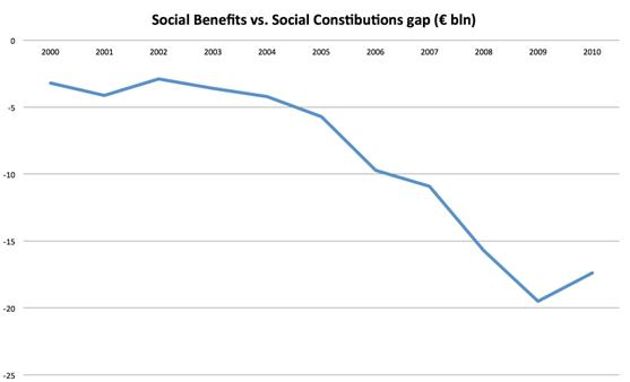

At the same time, the gap between social contributions and the payments of social benefits widened, putting serious strain on Greece’s fiscal position, which those in charge chose to ignore.

Greece began consistently running deficits that exceeded 10 billion euros and failed to record a surplus before interest payments from 2003 onwards. The global financial storm of 2008 found Greece in a precarious fiscal position - from 2007, the deficit had exceeded 15 billion euros and in 2008 the primary deficit was well above 10 billion. A global liquidity drain was approaching for a country that needed well over 20 billion euros in financing to keep it solvent.

Adding this volume of debt each year, it was not surprise that Greece’s political establishment managed to double the country’s public debt between 2000 and 2009. In 2009 alone Greece issued 66 billion euros (equivalent to 28 percent of the economy) to roll over existing and deficit financing.

After 2004, Greece’s debt as a percentage of GDP rose above 110 percent and shot up to 129 in 2009, effectively sealing the country’s fate and insolvency.

The drama that surrounds Greece even to this day and the degree of the economic and social devastation that this crisis has caused often lead to conspiracy theories. But looking at the numbers tends to concentrate minds and lead to reality checks.

Without a shred of doubt Greece needs to have a thorough introspection for the reasons that it ended up being a global pariah, going cap in hand to others. Narrowing this internal search to the last five years is the typical response of a political establishment that does not know what to do without barbarians.

Follow Yiannis on Twitter: @YiannisMouzakis

Great analysis from Macropolis. Thanks.