-

Podcast - How much is Greece getting out of the RRF?

Podcast - How much is Greece getting out of the RRF?

-

Podcast - Between investment grade and rule of law: Greece's contrasting images

Podcast - Between investment grade and rule of law: Greece's contrasting images

-

Where is Greek growth coming from?

Where is Greek growth coming from?

-

Bravo, Bank of Greece

Bravo, Bank of Greece

-

Podcast - A year on from Tempe train crash, trust fades as questions mount

Podcast - A year on from Tempe train crash, trust fades as questions mount

-

Podcast - SYRIZA embraces the chaos

Podcast - SYRIZA embraces the chaos

An impossible choice

As this article was being written a few days ago, various European governments and international funding institutions were discussing the consequences of the expiration of Greece’s current financial assistance programme. Equally, ministries across the euro area were considering the Tsipras government’s last minute requests to extend for a short period of time the former programme while simultaneously beginning negotiations on a third, new financial assistance framework.

In the meantime, deadlines have expired, Greece as a eurozone member is in payment default with an international creditor and the government in Athens is redrawing its red lines by the day. Letters from the prime minister have reached the troika of institutions too late for any reconsideration of their own demands.

If the reader feels confused about all these developments, you are in good company. The twists and turns of the past couple of weeks between Athens and its international creditors are indeed mind boggling and unprecedented. Six meetings of eurozone finance ministers, one extraordinary EU summit in Brussels, countless teleconferences and the relentless exchange of proposals, non-papers as well as deliberate leaks.

Sandwiched in between this past fortnight are the Greek citizens. They are at the receiving end of all these erratic developments. They have to digest the call for a referendum on Sunday 5 July, after waking up on Monday to closed banks across the country and the introduction of capital controls.

Furthermore, on Wednesday this week the public in Greece had to come to terms with the fact that the government’s non-payment to the IMF puts their country in a league of its own in Europe. Greece is now on course to become a financial pariah inside the eurozone.

Another payment deadline, of much larger proportions to the ECB, lies just around the corner on 20 July. Within the next 17 days, the political authorities in Athens are at risk of defaulting to a second international creditor and member of the troika of institutions.

The introduction of capital controls was not unexpected for Greek citizens. In light of the massive deposit outflows in recent months, speculation was rife that they were on their way. Indeed, MPs from the governing and opposition parties in parliament frequently spiced them up as a viable option.

What rather shocked Greeks were the long queues of desperate elderly citizens unable to collect their pensions. They rely on cash transactions because they do not use or own a debit card and therefore were unable to withdraw the new limit of 60 euros from ATMs.

These citizens felt insulted at having to stand in the July heat, depending on the first letter of their surname, in order to access their account. For a government that proclaimed the word “dignity” in capital letters in recent months, this treatment of senior citizens was an outright scandal and disgrace.

Supply shortages and frustration are now starting to appear not only at ATMs but also in supermarkets, pharmacies, public hospitals or petrol stations. Cash is quickly becoming the only mode of payment accepted by domestic suppliers, public institutions and foreign companies.

If we needed to understand how almost overnight a domestic economy changes its modus operandi when banks are closed and cash is king, then the past five days have been a huge learning curve. But that may only be the start of our experience, and possibly the easier part of the journey ahead.

The Greek people’s resilience and patience in these challenging times has been remarkable and stands in stark contrast to the behaviour of politicians from the governing and opposition parties. It took the two mayors from Athens and Thessaloniki to inject the appropriate level of reasoning into the referendum debate. They addressed civil society on Syntagma Square in a respectful and measured manner that is so blatantly lacking in the mainstream politicians from the radical left to the conservative fold in Athens.

From the international creditor’s perspective, two competing pressures with regard to the referendum are at play. The first is their concern of a No prevailing in Sunday’s vote. The troika of institutions understands that Tsipras can use such a result as leverage in any subsequent negotiation process. But reopening the expired terms of reference of the second financial assistance programme for Greece appears a rather unlikely strategy.

The eurozone finance ministers, IMF, ECB and European Commission are reluctant to do just that. Instead, they have taken the line of argument to accept holding the referendum and emphasising that the democratic process is in play in Greece. The political calculation of the institutions is rather straightforward, but constitutes a high-risk strategy: They hope for a Yes vote and expect that either a cabinet reshuffle or an outright change of government (coalition) may follow Sunday’s vote.

Thus their embrace of the referendum is not a sudden re-evaluation of the merits of Athenian grassroots democracy. Rather, it is a means towards other ends that should be called by its name clearly: regime change. The institutions’ belief is that a majority of Greeks will vote Yes on Sunday and thus force Tsipras into major concessions during subsequent negotiations with the creditors, provided he manages to stay in office.

But it will primarily be the Greek citizens and businesses that have to face the damage created and chart a course towards a careful rebuilding process. They have suffered during the past five years. They, younger and older generations alike across the country, are angry and confused. Humanitarian aid, as some foreign “experts” and politicians are starting to propose, will not alleviate, let alone solve, this misery and disillusionment.

Included in this endeavour is the necessary repair work concerning Greece’s standing in the international arena. Rebranding efforts by marketing strategists will not suffice. The matter goes deeper and requires a long-term effort.

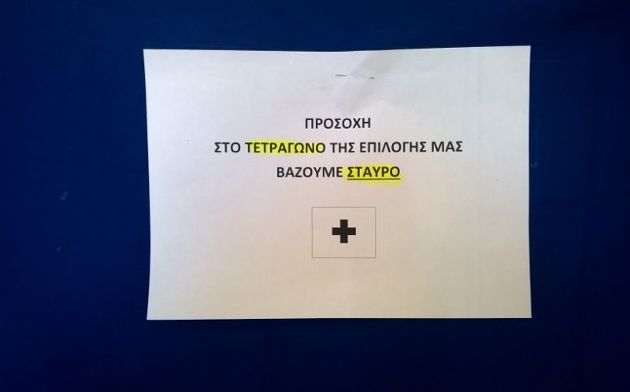

Thus, on Sunday voters will face a political and very personal decision when they take the ballot into their hands. They will have to make a decision based on a misleading question. The underlying consequences involved in this challenge will shape the country for years to come. Those voting for the first time face an impossible choice under these circumstances. They will be literally holding their future in their own hands while participating in the democratic process for the first time.

The past weeks have exposed fundamental flaws of governance in Athens and major deficits in the architecture defining membership of the single currency. Whatever the outcome of Sunday’s referendum, neither Greece nor the eurozone will ever be the same when we wake up for the start of a new week.

*You can follow Jens on Twitter: @Jens_Bastian. This article appeared in Friday's e-newsletter, which is available to subscribers online or via our free mobile apps (App Store and Google Play).

Great article Jens! Definitely clears up a good deal of confusion around the referendum question and shows that the yes or no outcome fails to address some key structural issues facing Greece and Europe. All the best, Matteo