-

Podcast - How much is Greece getting out of the RRF?

Podcast - How much is Greece getting out of the RRF?

-

Podcast - Between investment grade and rule of law: Greece's contrasting images

Podcast - Between investment grade and rule of law: Greece's contrasting images

-

Where is Greek growth coming from?

Where is Greek growth coming from?

-

Bravo, Bank of Greece

Bravo, Bank of Greece

-

Podcast - A year on from Tempe train crash, trust fades as questions mount

Podcast - A year on from Tempe train crash, trust fades as questions mount

-

Podcast - SYRIZA embraces the chaos

Podcast - SYRIZA embraces the chaos

Greece's labour market is austerity's biggest casualty

Greece has the potential to attain by 2020 a GDP in the region of 330 billion euros and a place in the G20, wrote the editor of a popular weekly newspaper in Greece over the weekend. This would require Greece to miraculously add 150 billion euros to its economy by the end of the decade at the same time as the 20th economy in the G20 experiences a depression similar to the one Greece has gone through in recent years. Leaving this unlikely scenario aside, the tone of the editorial captures the efforts during the festive period to change the narrative of the country’s future prospects.

Prime Minister Samaras and Finance Minister Stournaras, seem to have placed all their chips on the gradual improvement in sentiment towards and, most importantly, within the country as “drachmophobia” and “Grexit” fade away. They both expect a slow recovery of economic activity in the second half of the year, while on the fiscal side – assuming there are no accidents on the political front – the majority of the 2013 measures are on the expenditure side (as long as measures are implemented as planned and the recession does not exceed the finance ministry’s estimates) and the revenue side of the budget should be executed without any unexpected challenges. Greece next year could have a primary surplus of approximately 700 million euros and for the first time in over a decade spend less than it actually collects, excluding interest payments.

As much as it is essential to end the misery and finally have every participant in the public debate working to create a national plan that will eventually get the country out of this crisis, hopeful editorials and changing sentiment alone are not enough for the country to alter course and address the biggest casualty of the policies subscribed over the last three years, the labour market.

Between the last quarter of 2009 and the third quarter of 2012 – the last available quarterly data from ELSTAT – the Greek economy has lost 738,000 jobs, a 16.5% reduction in the number of employed. Three industries lead the losses with a combined 424,000 jobs. The lion’s share comes from construction that has lost 159,000 jobs, a staggering 43.8% drop in employment, followed by manufacturing with 137,000 job losses, a 28% reduction, and then wholesale and retail trade with 127,000, a 16% drop.

The fourth and first quarters of each year are traditionally the ones with lower employment due to the seasonality of economic activity. Compared to the third quarter, the fourth quarters during the crisis years have seen job losses as follows: 49,300 jobs in 2009, 90,200 jobs in 2010 and 147,600 jobs in 2011. Equally on a quarterly basis, the first quarter of 2010 had another 72,400 jobs lost, 80,500 jobs in 2011 and 94,200 during the first quarter of 2012.

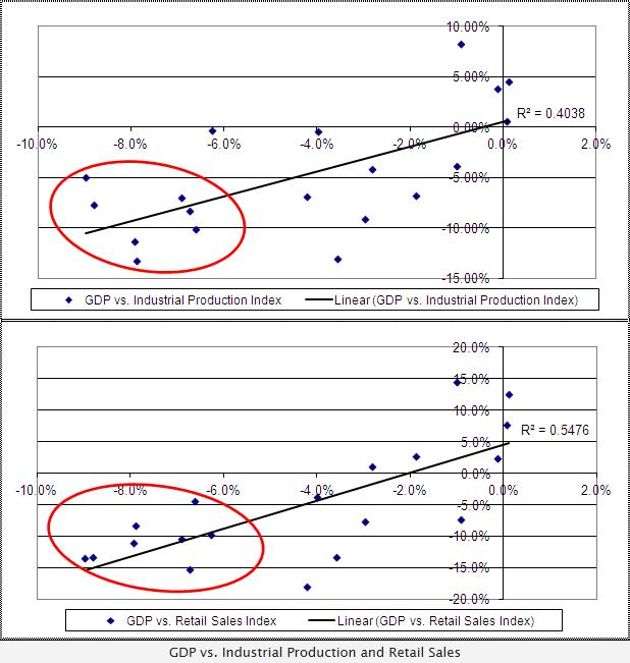

When plotting the annual changes of the GDP against the equivalent changes in industrial production and retail sale indices, the correlation is evident and since the crisis began there is a roughly 1 for just over 1 percentage impact between GDP drop and industrial production and 1 for 1.5 relationship between GDP and retail sales (circled in red). Today, Industrial Production for November of last year reported another fall of 2.9% on an annual basis.

Plotting the retail sales index against the wholesale and retail jobs, during 2012 there is a relationship of approximately 8,000 jobs lost for every point drop of the index. The equivalent relationship when plotting the industrial production index against manufacturing jobs is approximately 10,000 jobs for every point drop of the index.

While keeping in mind the relatively brief period observed, if the relationships between GDP, industrial production, retail sales, manufacturing and wholesale/retail trade jobs follow the pattern of the last few quarters – and there is an absence of any significant developments in the short-term to change the current course – there is a probability that by the end of the first quarter of 2013 an extra 40,000 jobs might have been lost in the retail and wholesale sector and 30,000 jobs lost in manufacturing. If jobs in the construction sector follow the recent trend and hold their relationship with the collapsing construction activity, the industry could see a further 10,000 jobs lost. Adding a conservative estimate of 20,000 job losses in the accommodation and food service activities, the Greek economy could see 100,000 jobs lost from just four industries. If the rest of the sectors continue their current trend, the end of the first quarter of this year could find Greece with 1.4 million unemployed and an unemployment rate of 28% even if the pace of job losses slows down.

The domestic debate is full of references to jobs but no one, the government included, has presented a comprehensive plan to address the issue of unemployment.

The construction sector saw its peak in employment in the last quarter of 2007 when the production index in construction stood at 158.5, building activity was 79.5 million cubic metres and building permits at 77,400. In the third quarter of 2012 the index was 41.4, building activity was 2.4 million cubic metres and the building permits 3,663. With 197,000 jobs lost, an estimated 200,000 properties in stock, the state repeatedly reducing the public investment budget, falling property prices, tight credit conditions and a heavily taxed property ownership in the country, the chances of the industry even in the long term absorbing back these jobs seem slim.

Manufacturing had its employment peak in Q4 2006. During that quarter, household consumption was growing at an annual rate of 6% and banks were calling customers to sweet-talk them into accepting their “low rate” credit cards and loans. With domestic disposable incomes reduced on average by 25%, even if exports substitute some of the domestic demand, there seems to be no clear vision how the manufacturing industry and which sectors will absorb the 208,000 jobs that have been lost.

In a similar fashion, the peak in the wholesale and retail sectors was 837,000 jobs in Q1 2009. In Q3 2012, it was 664,600. Aside from the favourable conditions in domestic demand and credit, in 2007 and 2008 Greece was importing on average 16 billion euros worth of goods each quarter. The quarterly average for 2012 is 9 billion euros. Much of this peak in employment was coming from small and medium-sized retailers and professions revolving around the car industry, sectors that have been hit severely by the crisis or businesses that simply do not exist anymore.

When one looks deeper into the latest quarterly labour survey the signs are even more alarming.

Out of the 1.23 million unemployed in September last year, 62.6% of them are unemployed for over one year, which makes it even more difficult for them to be re-hired, gradually losing touch with the labour market. One in four, 24.7%, of the unemployed population are new entrants in the labour market. Unemployment for women is already at 28.9% and 13% of those women that are highly educated with a postgraduate degree still cannot find a job – the equivalent rate for men is 12.3%.

Youth unemployment catches the press headlines but more alarming for a society that wants to exit a crisis is that the 25-29 group, that recently finished its education and sets the foundations for a future career cannot find a job at a rate of 38%, the unemployment rate for women in that age group is 41.4%.

At regional level, there are regions like Western Macedonia in the north that have passed or are close to the 30% unemployment mark. Spinning factories were major employers in those regions, factories that started closing down even before the crisis.

These are devastating figures that indicate deep and structural unemployment issues further complicated by the fact that are they tightly linked with the old economic model in Greece. A model where the state was a major employer and business generator and cheap credit was readily available after the adoption of the euro, credit that boosted consumption, state borrowing and spending, creating a wealth effect.

Changing the economic model built up over decades does not happen overnight and while Greece could start performing fiscally, reporting modest growth rates, the economy would have established a natural rate of unemployment above 15%. Compounding the issue is the fact that Greeks by the thousands are leaving for countries that offer employment opportunities for the unemployed or better career prospects for those already employed but who have seen their wages and disposable income repeatedly reduced. In Germany alone, according to the Federal Employment Agency more than 123,000 Greeks found employment in 2012, an 11% increase compared to 2011.

Greece could find itself in such a situation that when the economy picks up, the labour market will not have the required skills for growth in value-added sectors, unable to attract the required skills for new industries and facing the risk of ending up in a labour intensive, low value-added economy status.

Irrespective of the timeframe and from any angle you look at it, unemployment is by far the biggest problem in Greece today and should be the government’s main focus. Even a government with the best of intentions will not be able to count on society’s support for an extensive reform process and a heavy fiscal consolidation when close to one in three of the active population will end up being out of a job or underemployed. For a political establishment whose credibility is repeatedly battered, the task is close to impossible.

Optimism and positive attitude are important when dealing with a crisis but they certainly do not get people back to work. It is time for a real plan.