-

Podcast - How much is Greece getting out of the RRF?

Podcast - How much is Greece getting out of the RRF?

-

Podcast - Between investment grade and rule of law: Greece's contrasting images

Podcast - Between investment grade and rule of law: Greece's contrasting images

-

Where is Greek growth coming from?

Where is Greek growth coming from?

-

Bravo, Bank of Greece

Bravo, Bank of Greece

-

Podcast - A year on from Tempe train crash, trust fades as questions mount

Podcast - A year on from Tempe train crash, trust fades as questions mount

-

Podcast - SYRIZA embraces the chaos

Podcast - SYRIZA embraces the chaos

Holding out for a (reformist) hero

Since the start of the Greek crisis, many international commentators (as well as locals) have been holding out hope that a reformist white knight would emerge from the political morass and ride to Greece’s rescue. Reality, though, has been equally consistent in shattering their illusions.

In the beginning, George Papandreou, with his foreign upbringing and diplomatic skills, appeared the right man to lead Greece out of the fiscal mess left by his predecessor. However, it gradually became apparent that a good command of English and feeling comfortable on the international stage were not sufficient qualities to confront the complexities of Greece’s demanding political and economic situation.

Papandreou proved as poor at managing Greece’s problems at home as he was at communicating them abroad. However, his relationship with European counterparts did not break down irreparably until 31 October 2011, when he announced plans to hold a referendum on the second bailout package.

After the announcement, Papandreou’s feet barely touched the floor as he was removed from power and replaced by Lucas Papademos, the former European Central Bank vice-president.

Papademos, with his years of experience in Frankfurt and at the Bank of Greece, was the next figure to carry the hopes of European decision makers. To a certain extent, though, his hands were tied from the start as New Democracy leader Antonis Samaras only agreed to be part of the three-party coalition government on the proviso that snap elections would be held as soon as possible.

Nevertheless, beyond the smooth execution of the PSI, the first restructuring of Greek public debt, the Papademos government proved a bit of a damp squib. While the former central banker ticked many of the boxes, he carried little political weight within Greece and the burst of structural reforms that some outsiders expected and many locals hoped for never materialised.

The next figure in which many outside Greece invested was Samaras himself. Having antagonised Greece’s lenders by vehemently opposing the first bailout, Samaras softened his position as he got closer to power and, after winning the June 2012 elections and heading a new three-party government, performed a political triple Salchow by deciding to implement the second bailout.

“Nobody is without sin,” Samaras told journalists in Berlin during a visit to German Chancellor Angela Merkel when he was questioned about his earlier stance. And with that, the slate was wiped clean and Samaras’s government started to deliver, on the fiscal front at least.

With the anxiety triggered by Papandreou’s referendum plans and the tight elections in the summer of 2012 dying down, many international commentators felt that Greece was back on track by early 2013 and that Samaras had gone from being the eurozone’s bête noire to its great white hope.

However, by the summer of 2014, Samaras too was on the way to dashing hopes that he would be a champion of reforms in Greece. His government’s appetite started to wane as the European Parliament elections of May 2014 approached and it did not look like the promise of debt relief from the country’s lenders would be fulfilled soon.

After losing to SYRIZA in the May vote, as well as performing poorly in the local elections held at the same time, Samaras abandoned all pretences and packed his cabinet full of party hacks that could engage in a political battle with the leftist party rather than implement the measures being demanded by the troika.

As it became apparent that Samaras would not be in power for much longer, new murmurings of hope emanated from European capitals: Maybe Alexis Tsipras would be prepared to do a deal with PASOK and the newly formed centrist Potami party, transforming him into the Greek version of Brazil’s Lula, rather than Venezuela’s Hugo Chavez.

However, this bubble also burst when Tsipras decided to form a government in January 2015 with the staunchly anti-bailout (in rhetoric at least) Independent Greeks. In the ensuing months, Tsipras became the enfant terrible that many European policymakers had dreaded. However, his decision to sign up to a third bailout and his political durability despite making that choice means that Greece’s lenders have no option but to deal with him and his often erratic administration.

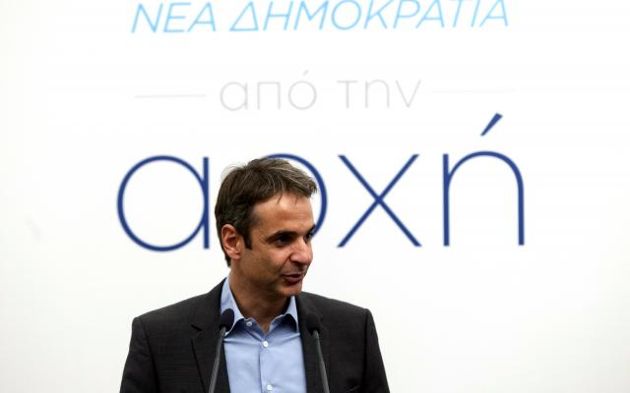

Nevertheless – and despite numerous false dawns – the desire outside Greece for a reformist hero to emerge and fix the country’s problems remains. The latest candidate for this position is former administrative reform minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis, who caused an upset by winning New Democracy’s leadership vote on Sunday.

Ahead of Sunday’s election, several articles appeared in the German and English-language media casting the former administrative reform minister as a new potential miracle worker, or “Harvard-educated free-market reformer”, as the Wall Street Journal describes him. Incidentally, the term “Harvard-educated” also appeared before Mitsotakis’s name in the Financial Times, the Agence France-Presse and other international media outlets. While his education is a point of reference for an international audience, it is also something that occurred almost 30 years ago. The frequency with which it is used suggests a certain degree of orientalism in the coverage.

Reformer?

The scramble to constantly find someone’s cause to champion appears to have blinded some commentators to reality. While Mitsotakis is affable, forward-looking and appeared to work well with the country’s lenders, this does not necessarily qualify him as an accomplished reformer. It is one thing to favour reforms and quite another to carry them out, especially in a country like Greece where an obstacle course of determined interest groups, non-cooperative civil servants, serpentine bureaucracy and weak political will have to be overcome.

The Wall Street Journal writes that Mitsotakis won “respect from Greece’s creditors for his efforts to streamline the dysfunctional public administration and introduce new concepts such as promotion on merit”. However, the figures show that by far the biggest reduction in civil servant numbers (down by around 160,000 from 2010 to 2014) took place during the premiership of Papandreou, the one-time reformist knight now regarded as failure. Also, the WSJ’s assessment does not seem to tally up with the International Monetary Fund’s assessment in its most recent review (summer 2014, more than a year after Mitsotakis was appointed administrative reform minister), in which it lamented that exits from the public sector had mostly been limited to “narrow groups” and “have not been based on performance”.

While Mitsotakis presided over the departure of hundreds of school guards and Finance Ministry cleaners, as well as the entry of university administrative staff and municipal police into a mobility scheme, this seems a scant evidence on which to declare him capable of seeing through structural reforms. Perhaps given more time (he was in office for 19 months) and more backing from his prime minister and colleagues he could have achieved more. For now, though, there seems little basis for heaping praise on him and it would be best to reserve judgment.

History unfavourable

Beyond Mitsotakis’s record, though, there are several reasons to believe that those hoping for the emergence of an inspirational progressive figure will be disappointed. Firstly, recent history is against them. Their hopes have been repeatedly dashed over the last few years largely due to a fundamental misunderstanding of Greek politics, particularly the qualities needed to appeal to a range of constituents rather than the urban and business elite, as well as the way in which the notion of reforms have become so intertwined with the politically poisonous process of fiscal adjustment.

Indeed, the first task that Mitsotakis faces is to convince his own party that his belief in liberal economic reforms is the way forward. New Democracy is a party of many factions and the liberal, reformist wing is by no means the dominant one, despite Mitsotakis’s win on Sunday, which was helped by a dollop of incompetence from those who opposed him.

“Do we want a [Margaret] Thatcher-style party obsessed with the euro or a New Democracy of radical liberalism with a social face that will not just represent the economic elite?” said veteran New Democracy MP Nikitas Kaklamanis recently of the choice between Mitsotakis and rival candidate Evangelos Meimarakis. This is the kind of scepticism that the new conservative party leader, whose candidacy had limited support from New Democracy lawmakers, will have to overcome. Mitsotakis also stands in a minority within his socially conservative party when it comes to non-economic issues. He was one of only 19 out of 75 New Democracy MPs to vote in December for a law allowing same-sex civil partnerships.

Ensuring that liberal thought takes root within his party when it also has limited appeal among Greek voters (the local political landscape is littered with liberal parties that have tried and failed), will also be a big test.

It is also worth noting that a Mitsotakis-led New Democracy will provide a much clearer ideological opponent to SYRIZA. This could work to the new leader’s advantage but it could also make it much easier for Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras to paint Mitsotakis, the son of former party leader and ex-prime minister Konstantinos Mitsotakis, as representing the elites. The former minister is likely to be particularly tested when it comes to the government’s negotiations with Greece’s lenders. If he is seen taking positions that are more economically liberal than those advocated by the institutions, Tsipras will use this against Mitsotakis as ardently as possible.

Political ruins

Secondly, Greece is in the process of a political transition that has undermined traditional parties as well as blown a hole in the political centre. To expect one man or woman to come along and rectify this devastation is unrealistic. Like other eurozone countries where the traditional political forces have been deemed to have failed and the impact of austerity has eroded patience, uneasy and weak alliances seem to be what lies ahead in Greece’s short-term political future. In this environment, the skills that are most in demand are not necessarily how to overhaul the country but how to build the political alliances that can create the conditions for such change. There is no reason to believe that someone cannot do both but it should be clear that each requires a different skill set.

Finally, the belief that someone (especially a figure that has been part of the political scene for more than a decade and who is the member of a political dynasty) can magically re-energise Greek politics overlooks the overwhelming lack of trust among voters. Since the start of the crisis, support has swung from PASOK to New Democracy and then to SYRIZA, while also fragmenting into many smaller pieces along the way. Each time, voters have been disappointed, each time voter turnout has dropped and each government’s life has been cut short.

Mitsotakis has to be applauded for an energetic, positive campaign that attracted support from non-traditional New Democracy voters but in the post-election enthusiasm we should not overlook the fact that his win was surprising but not overwhelming (52.4 vs 47.6 percent), which means that around 175,000 people voted for him. To put it into perspective, this is about how many people voted for anti-bailout Popular Unity in the September 2015 elections, while ex-finance minister Yanis Varoufakis won 142,046 votes in last January’s elections.

If you add the fact that New Democracy has suffered four consecutive election defeats (European Parliament vote in May 2014, general elections in January and September 2014 and the bailout referendum in July 2014), while losing some 200,000 voters between January and September last year despite Alexis Tsipras’s manic time in office, it is clear that Mitsotakis has much work ahead of him. Some expect that he will immediately begin attracting voters from centrist To Potami. This may the case, meaning Potami’s days could be numbered. But it should be highlighted that just 222,000 Greeks voted for the fledgling party in the September elections, which does not represent a bottomless reservoir from which the former minister can draw support.

Mitsotakis’s victory undoubtedly gives Greek politics a shot in the arm after a dismal period. It also provides hope that New Democracy might go through a period of renewal, transforming it into a modern centre-right party that shares European values. There is also the potential that a dynamic opposition will prevent the current coalition from acting with impunity. However, the simple fact of the matter is that in a country that continues to be in recession seven years after its economic crisis began, remains saddled with an unsustainable public debt and continues to operate within the constraints of an adjustment program that is entering its sixth year, no single person can be transformative. There is no figure in Greece at the moment that carries that much political weight and personal charisma.

*An earlier version of this article appeared in Friday's e-newsletter, which is available to subscribers. To find out more about subscriptions, click here.

You can follow Nick on Twitter: @NickMalkoutzis

Reforms imposed by the german occupation regime are not true reforms. Mitsotakis is the best the conservative camp has at the moment. There is not even a close second.