The men who would be prime ministers

There has been much consternation in Greece over the last few years about the economy’s inability to grow and produce sectors that can flourish. The country’s politicians have come up with a unique way of tackling this problem by creating a growth industry of their own: founding new political parties.

Since Greece signed its first bailout agreement in May 2010, nearly 40 new political parties have been launched. Most have withered and died. Some, like Independent Greeks and Potami, have managed to survive. The drive for this churn of personalities, slogans, banners and logos is provided by elections, of which there has also been no shortage in recent years.

During the “memorandum era”, Greece has had four national elections, building on a rich tradition of governments not seeing out their four-year terms. The last time a Greek administration stayed in power for its full term was in 1989, the year that the Berlin Wall fell. Since then, there have been 12 general elections.

The frequency of polls has undermined the stability that any country’s economy needs to grow. With each change, or return, of government, key public sector personnel has changed, policies have been rethought and legislation rewritten. Each time, the economy has had the rug pulled out from under it.

Maybe this is the price Greece has to pay to ensure that its citizens’ democratic right is safeguarded. It is an argument that would make for an interesting debate.

What is less open to discussion, though, is the folly of opposition leaders (especially over the last decade) who have pushed and pulled incessantly for snap elections just so they can inherit a terrible state of affairs they are totally unprepared to deal with.

This pattern has been repeated a number of times recently. PASOK’s George Papandreou began calling for new elections almost from the day that his party lost to New Democracy in March 2004. He was undeterred by the fact that when the snap polls came in 2007 his party was beaten again. Despite the economy entering recession, Greece being monitored for its oversized public deficit and state finances heading off the rails, Papandreou continued to sue for snap polls. He got them in October 2009 and found himself at the country’s helm as it rammed into the iceberg.

Not content with having seen Papandreou being forced to deal with Greece’s biggest economic crisis of recent times and to adopt a harsh austerity programme as part of the biggest international bailout in history, the then New Democracy leader Antonis Samaras felt it would be a good idea to try to force elections as soon as possible.

Having refused to vote for the first bailout and then proposed an illusory exit from the programme through his Zappeio I and II economic plans, Samaras agreed in 2011 to join a three-party coalition with PASOK and the Popular Orthodox Rally (LAOS) on the condition that the administration would be disbanded as soon as possible and new elections held.

This happened just a few months after the interim government led by ex-central banker Lucas Papademos signed Greece’s second bailout. Samaras won the May and June elections in 2012 on the promise of renegotiating the deal that Papademos had accepted. His resistance lasted only a matter of days and soon he too was implementing an agreement similar to the one he had chased Papandreou out of town for.

Within two years, Samaras had lost one of his coalition partners, suffered a defeat in the European Parliament elections and seen his relationship with Greece’s creditors deteriorate to the point that he could not clinch an agreement to conclude the bailout review at the end of 2014 that would have seen him stumble over the line and take Greece out of the adjustment programme.

Despite seeing Papandreou and Samaras fall flat on their faces, SYRIZA leader Alexis Tsipras somehow thought it would be a good idea to press for snap elections in the same way they had. His chance eventually came in December 2014, when he triggered a national ballot after refusing to support Samaras’s candidate for Greek president.

In just the matter of a few months, Tsipras also had to eat his words. Vows to tear up the existing bailout agreement and never sign a new one soon dissolved to dust and the leftist politician found himself in the same embarrassing position as his predecessors, signing Greece’s third rescue package and adopting the very measures that he had campaigned against.

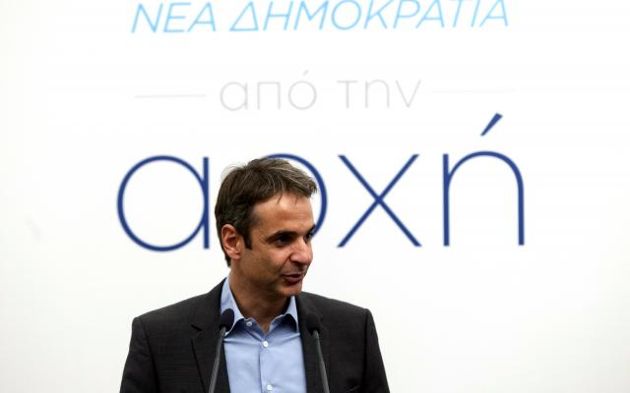

So, it was astonishing last week that New Democracy leader Kyriakos Mitsotakis, a politician who presents himself as being more thoughtful and urbane than his colleagues, should call for Tsipras to resign and snap elections to be held.

It came as a surprise primarily because of what has gone before, when cocky opposition leaders accused the government of making a mess of things only to find that they could not do much better when they took over. Why would Mitsotakis even want to flirt with the idea of snap polls when the bailout review has not been completed and the refugee crisis is in full flow? Being put in charge of these twin crises would snuff out even the ablest politician’s career.

It is also not clear exactly what alternative Mitsotakis would be offering at this stage. He would still have to close the review, maybe by changing some of the measures, and implement the EU–Turkey agreement with regards to the refugee crisis. During his admittedly brief leadership of the party, Mitsotakis has not yet given any indication of having a substantial alternative to offer. His pledge, for instance, of a comprehensive and costed pension reform plan was reduced to a few bullet points.

Urging for snap polls just six months after the last ones were held also raises questions about his credibility. Apart from the fact that it seems unbelievably early to be calling for yet another round of voting, at the beginning of February Mitsotakis indicated that he had no intention of pushing for early elections. “I am not in a rush to become prime minister,” he told Skai TV.

Greeks have paid dearly for the headstrong rush to power made by its last few prime ministers. If Mitsotakis genuinely wants to represent a different, new breed of Greek politician, perhaps a good point to start from would be to show that, unlike those that have gone before him, he has more than the same single string to his bow.

*This article first appeared in last week's e-newsletter, which is available to subscribers. More information in subscriptions can be found here.

You can follow Nick on Twitter: @NickMalkoutzis

Podcast - Whose property? Greece’s housing challenges

Podcast - Whose property? Greece’s housing challenges Can the Green Transition be just?

Can the Green Transition be just? Where is Greek growth coming from?

Where is Greek growth coming from? Bravo, Bank of Greece

Bravo, Bank of Greece