-

Podcast - How much is Greece getting out of the RRF?

Podcast - How much is Greece getting out of the RRF?

-

Podcast - Between investment grade and rule of law: Greece's contrasting images

Podcast - Between investment grade and rule of law: Greece's contrasting images

-

Where is Greek growth coming from?

Where is Greek growth coming from?

-

Bravo, Bank of Greece

Bravo, Bank of Greece

-

Podcast - A year on from Tempe train crash, trust fades as questions mount

Podcast - A year on from Tempe train crash, trust fades as questions mount

-

Podcast - SYRIZA embraces the chaos

Podcast - SYRIZA embraces the chaos

Could reforms have prevented Greece's economic collapse?

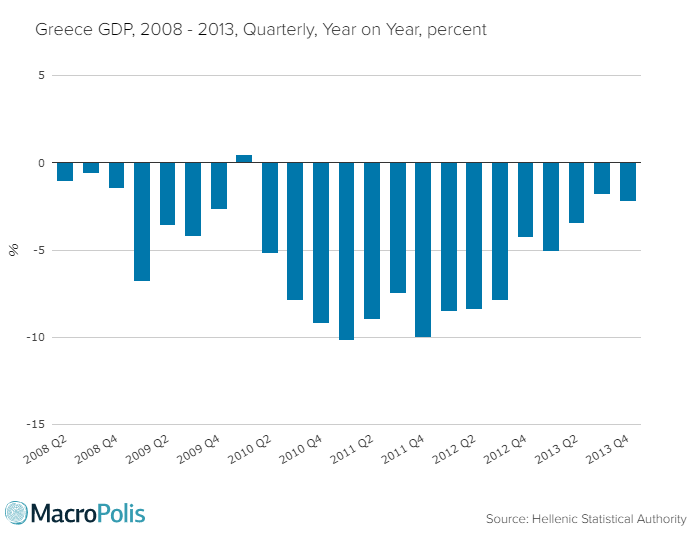

The Greek economy’s collapse in the 2010-2013 period has become legendary. Greece had already been hit hard by the global financial crisis in 2009, when it posted a sharp GDP drop of -4.3 percent. This set the stage for what would become the deepest economic contraction of a developed country in history and would draw frequent comparisons with the Great Depression.

In 2010, the year in which the country’s fate was sealed and it began the first of three successive adjustment programmes, contraction accelerated to -5.5 percent before reaching the depths of -9.1 percent in 2011, followed by a -7.3 percent shrinkage in 2012 and a more modest -3.2 percent in 2013.

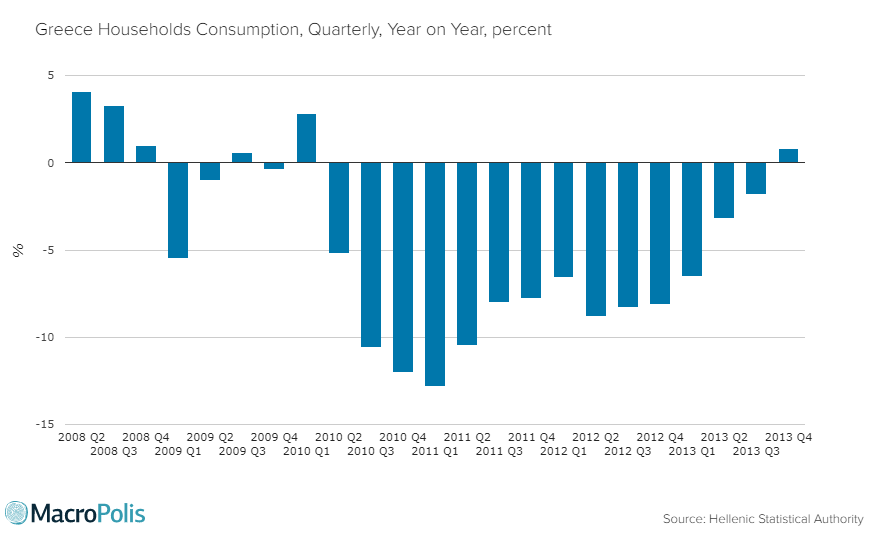

Private consumption went into freefall, posting accelerating double-digit decreases in the range of -10.6 and -12.8 percent between Q3 2010 and Q1 2011. The cumulative drop of private consumption in the 2010-2013 period was close to 27 percent.

Government spending was significantly curtailed in the effort to correct a primary deficit of 24 billion euros in 2009, with reductions in government expenditure reaching as much as -14.6 percent in Q3 2012.

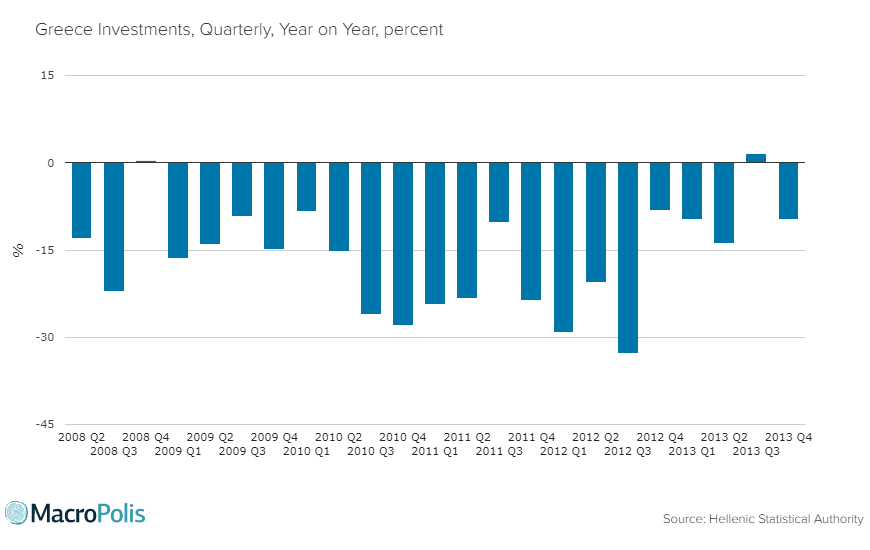

Investments tanked each quarter, dropping by around 25 percent between Q3 2010 and Q2 2011. The deepest drop was posted in Q3 2012, when it fell by 32.8 percent.

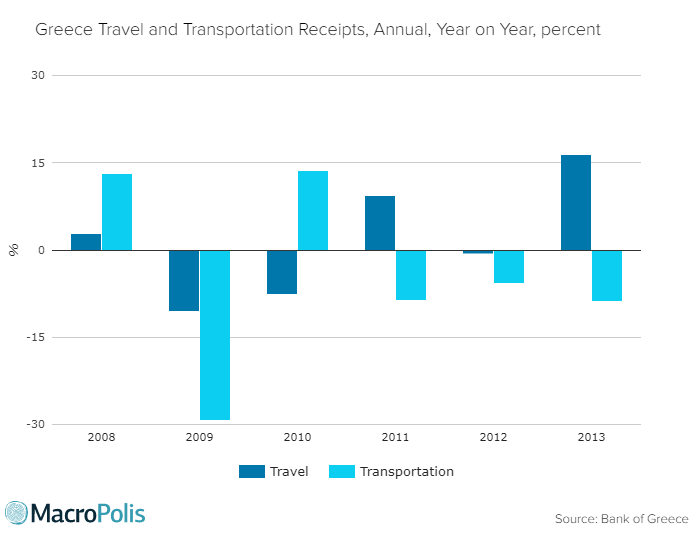

Greece’s exports felt the pain and even receipts from services, which are considered one of the country’s strong features due to tourism and shipping, experienced sharp drops in 2011 and 2012. The trade deficit did improve, though, via the sharp drops in imports as domestic demand collapsed across the board.

Receipts from services dropped from 34.2 billion euros in 2009 to 28 billion in 2013, having lost almost 7 billion euros from transport receipts.

Together, all these factors combined to shrink the Greek economy by a quarter between 2010 and 2013.

Greece’s lenders, who had a leading role in setting and authorising policy over the 2010-2013 period via the programme conditionality for loan disbursements, argue that one of the main reasons for this unprecedented loss of output was poor implementation of structural reforms. The theory is that reforms would have offset the contraction via supply side response and gains, if appropriately owned and implemented.

In the document following Greece’s latest request for a precautionary Stand-By Agreement, the IMF argues its rather conservative case on Greece’s long-term growth potential by looking at historical evidence of reform efforts and their economic payoffs. Indirectly, the Fund sheds light on the question of whether structural reforms could have taken hold quickly and had the kind of impact that could have prevented Greece suffering an economic catastrophe.

The Fund draws evidence from the extensive work on reforms that were published in Chapter 3 of the IMF’s April 2016 World Economic Outlook (WEO) and from an internal research paper that examines six prior cases of reforms in product and labour markets.

Both pieces of research highlight that reform gains are hard to quantify and measurement techniques find it difficult to attribute gains solely on reforms and how other factors interact and influence economic outcomes. However, there is enough evidence to indicate that reforming product and labour markets generate GDP benefits but that “the gains from reforms are somewhat modest and transitory,” as the IMF concludes.

More specifically, WEO 2016 examines reform cases from the 1970-2013 period, looking at a wide range of structural interventions in product and services markets, opening closed professions, labour market policies, collective bargaining, privatisations. These are essentially similar to the efforts to deliver competitiveness gains that Greece has been asked to implement. The wide time horizon gives an opportunity to assess reforms outcomes under various macroeconomic and monetary conditions.

Evidence suggests that reforms generate GDP gains that average 3 percent over an eight-year period after which their impact on growth fizzles out, averaging an 0.4 percent annual gain.

The IMF finds that economic conditions matter to a large degree, as undertaking reforms in a contractionary macro environment and with monetary policy constrained lead to loss of economic output, since productivity gains need time to take hold. Meanwhile, making it easier to fire people often translates into firms letting go of employees and higher unemployment.

The internal research paper, which examines the reforms efforts of six advanced economies to ensure that it is comparing countries with similar characteristics for more robust results, comes up with very similar findings. The average impact of the changes is 0.6 percentage points annually over a period of five years, while in two of the six cases the gains were not significant.

It is undisputed that reform implementation in Greece fell short of any acceptable standards. It is also clear that if the country wants to have any chance of achieving the IMF’s modest growth projections and tackle the huge demographic challenges it will face in the coming decades, it needs to take ownership of structural changes that will enhance its growth prospects.

At the same time, as the IMF argues in its own assessment of the first Greek programme by the Independent Evaluation Office (IEO), “To be sure, even if structural reforms had been transformative, a quick supply response was unlikely.”

Even full implementation of reforms with a theoretical maximum impact in the high range of 0.6 percentage points would have gone up against economic contraction of between roughly 7.5 and 9 points the first two years of the programme.

Greece found itself in a position where formidable forces were interacting to drag the country down towards an economic depression. It needed to sharply correct a massive deficit in a short period of time due to eurozone loans being mostly purposed to service debt obligations, a collapse in liquidity for firms of all sizes that impeded productive investments, severe loss of disposable income and huge pressures in domestic demand as unemployment skyrocketed each month, the introduction of redenomination risk as member state and eurozone officials repeatedly questioning the country’s place in the euro.

These formed the perfect storm that battered into submission anyone that attempted to deal with it - from Greek governments fighting an uphill implementation battle to the troika itself, which conceded that the whole strategy needed a re-think as early as the beginning of 2011.

Simply claiming that all this calamity could have easily been avoided by the push of a single button is too facile a response and is not the answer deserved by those who saw their lives collapse over the last decade.

*You can follow Yiannis on Twitter: @YiannisMouzakis