-

Podcast - How much is Greece getting out of the RRF?

Podcast - How much is Greece getting out of the RRF?

-

Podcast - Between investment grade and rule of law: Greece's contrasting images

Podcast - Between investment grade and rule of law: Greece's contrasting images

-

Where is Greek growth coming from?

Where is Greek growth coming from?

-

Bravo, Bank of Greece

Bravo, Bank of Greece

-

Podcast - A year on from Tempe train crash, trust fades as questions mount

Podcast - A year on from Tempe train crash, trust fades as questions mount

-

Podcast - SYRIZA embraces the chaos

Podcast - SYRIZA embraces the chaos

Debt relief or debt restructuring for Greece?

The two economic adjustment programmes for Greece from 2010 and 2012 as well as the sovereign debt restructuring from April 2012 and the debt buyback initiative in December of the same year have had a significant impact on the debt profile of Greece as a sovereign debtor. Greece’s creditor structure in 2013 compared to the point of departure in 2010 hardly bears any resemblance.

Prior to the conclusion of the first economic adjustment programme more than 85 percent of Greece’s sovereign debt was held by private institutions. By contrast, following the twin debt restructuring and buyback exercise during 2012 over 80 percent of Greece’s sovereign debt now rests in the portfolio’s and budgets of the eurozone’s member states, the ECB’s and the IMF’s vaults as well as on the balance sheet of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM).

Turning the profile of Greece’s creditors entirely on its head has major implications for the political economy of the country’s debt overhang. This “drastic case of “credit migration” from the private into official hands” (Zettelmeyer et al. 2013, p. 35) is without precedent in the history of a sovereign debt restructuring exercise.[1]

Put otherwise, while in 2010 Greek sovereign debt was primarily held by German[2], French, Italian, Swiss and Japanese banks, the combination of two rescue programmes and debt restructuring have fundamentally altered the ownership structure of and accountability for the accumulated sovereign debt of Greece from the private to the official sector. Greece’s public creditors in Europe and Washington together now own roughly 84 percent of the country’s 320 billion euros in debt.

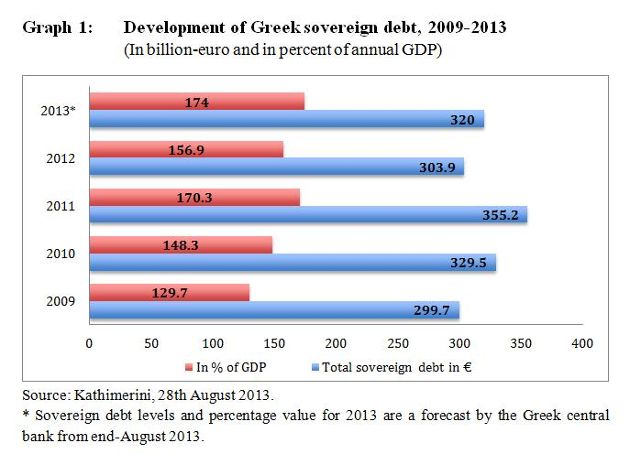

But what are the policy implications today of the aforementioned debt migration? The momentum from the private to the official sector has now firmly put on the agenda the follow-up issue of restructuring migration, i.e. from private sector involvement to official sector participation in debt restructuring. Given Greece’s current sovereign debt dynamics (see graph 1 below) it is a matter of time until this secondary migration process becomes a top priority on the political agenda of policy makers in Washington, Brussels and Frankfurt.

Against the background of this structural transition in Greece’s sovereign debt profile one has to interpret the emerging discussions about the eventuality of a third adjustment programme and/or further debt restructuring. The first two adjustment programmes for Greece from 2010 and 2012 have a combined volume of 240 billion euro. The current programme expires in mid-2014.

1. Who will blink first?

The negative comments from government representatives in Berlin arguing against a further (third) sovereign debt restructuring of Greece must primarily be viewed in the context of the recent federal elections in Germany. They were articulated by Chancellor Angela Merkel and her Finance Minister Wolfgang Schaeuble for the purpose of domestic political consumption. But that does not make the issue go away. The restructuring migration argument formulated in this article sheds light on a number of complex questions searching for clear-[er] answers:

-

Has this secondary migration process tied the hands of Greece as a sovereign debtor and created a prisoner dilemma for the Troika of international creditors? Who will blink first in the OSI debate? Who will continue to defend his privileged senior creditor status and insist on 100 percent payback?

-

Do the reasons that created the debt buyback in December 2012 only nine months after the debt restructuring still exist today? Put otherwise, are the structural factors in the debt dynamics of Greece still in play today that recently gave rise to the IMF breaking the taboo and calling for OSI at the European level.

-

The alternative to avoiding OSI is the continued ‘band-aid’ solution of maturity extensions on the time scale and further reductions in the already low 2.5 percent average interest rate on Greek debt. But how much does such a twin option constitute an attempt to kick the proverbial can down the road?

In the material assessment of the subject matter almost all sovereign debt experts and newly-established analysts of Greece are of the same opinion: The sustainability of Greece’s sovereign debt, which is rising again in 2013 in terms of debt-to-GDP ratios, is neither established today, nor guaranteed in the medium- to long-term.

It took no less than European Commissioner for Employment Laszlo Andor of Hungary to get to the heart of the matter. While he argued that Greece did not need a third bailout, Andor was honest to say that what Athens really needed was to be given debt relief.

“What Greece needs today is not a third bailout, but a proper reconstruction plan, which inevitably starts with a significant (emphasis added) debt relief and continues with programmes that bring fresh investments” (Kathimerini 2013).

Commissioner Andor’s debt relief assessment for Greece constitutes a substantial departure from the publicly articulated positions in Brussels and Frankfurt. Its merit is backed up by the current dynamics of Greece’s sovereign debt development with an economy continuing to shrink in its fifth year of recession. As graph 1 below illustrates, Greece’s debt-to-GDP ratio in 2013 is forecast to surpass 170 percent.

In absolute terms, according to the IMF and the Bank of Greece such a ratio corresponds to a total projected debt volume of 322 billion euro end-2013. The debt burden as a percentage of annual output in 2013 would surpass by more than 20 percent where Greece’s debt-to-GDP ratio stood in 2010, i.e. before the first economic adjustment programme and prior to the two debt restructuring exercises that took place in 2012.

With a debt-to-GDP ratio that is above 170 percent Greece would again reach the level of 2011, i.e. prior to the combined sovereign debt restructuring and buyback of 2012. In absolute terms both measures reduced the country’s sovereign debt load by 64 billion euros. This corresponds to a ratio of roughly 65 percent of Greek GDP.

This overall volume and ratio are unprecedented in the history of sovereign debt restructuring. Without both the debt restructuring and buyback operations from 2012 – totalling 126 billion euros or 65 percent of GDP - Greece’s total would today reach approximately 380 billion euro and correspond to a debt-to-GDP ratio of 208 percent!

2. The politics of debt sustainability

As a distressed sovereign, Greece is today not in a position to service its accumulated debt. Greece can only come closer to debt sustainability - and it is currently a stretch to speak of achieving it – if the reduction in the face value of accumulated debt is not offset by an increase in the price (yield) of servicing the remaining debt.

In order to accomplish this Greece will have to convince the troika of international creditors and market traders that it remains committed to a long-term structural reform process that also has the support of a majority of the population. Any change in this outlook – the fragility of coalition government, continued underperformance in the privatisation process, underachievement in tax revenue collection, a declining political will in favour of administrative reform – risks adversely impacting on debt sustainability and external creditors’ assessment of Greece’s performance.

The agreed sovereign debt objectives between the Greek authorities and the troika – 124 percent of GDP by 2020 and “considerably below” 110 percent by 2022 – will hardly be within reach if the structural dynamics of Greece’s sovereign indebtedness continues to grow as a result of the sustained economic recession.

It is equally noteworthy to underline that the definition of Greece’s debt sustainability is subject to a political designation and therefore does not constitute an exact science. In this observation are reflected the experiences of the past three years when it was not at all given that the three institutional members of the troika would apply the same measuring rod to the calculation of Greece’s sovereign debt and its medium-term sustainability.

More specifically, the IMF has been the most proactive troika member to repeatedly draw attention to the lingering issue of debt sustainability. The public controversies among the troika representatives about the critical issue and its implications in the case of Greece’s underachievement over time have given rise to the Washington institution pondering potential exit scenarios.

3. The international dimension of debt restructuring

It is also necessary to underline the international dimension of Greece’s debt restructuring arrangement and the outlook for its debt sustainability. Argentina’s sovereign debt restructurings over a decade ago have failed to reopen access to international debt markets. Ongoing litigation against Argentina highlights the leverage of holdout creditors.

-

Will Greece also have to wait that long? 12 years after Argentina’s original USD 100 billion default, the country is still a financial pariah on the international stage. Greece cannot afford to wait that long.

-

Nor can a eurozone member state be excluded from international capital markets for such an extended period of time and expect financial assistance from its international creditors. The rather generous treatment of holdout creditors in the Greek case, as Zettelmeyer argues (2013) may in fact enable Greece’s return to international bond markets sooner.

-

The decade-long unresolved situation with holdout creditors in Argentina, the experience with the twin sovereign debt restructuring exercises in Greece in 2012 as well as more recent developments in Belize and Jamaica (both in 2013) have prompted the IMF to launch a comprehensive internal review of the Fund’s policies and practices on sovereign debt restructuring arrangements. The Fund’s existing framework is incomplete, in particular when promoting an orderly sovereign debt restructuring mechanism (SDRM).

There was severe collateral damage from the exercise on Greece’s neighbour in the Mediterranean. The knock-on effects on Cypriot banks were immediate, and exploded into a full-blown crisis in April 2013.

-

The Cypriot example of forced burden sharing on account holders in excess of 100,000 euros is a debt exchange that sought to avoid the Greek route, including compensation for banks. Instead, the material result was the implosion of the banking sector and the first-time introduction of capital controls for a member of the euro area. These controls have now been in place for nine months and show no signs of being fully lifted, even if they have been somewhat reduced.

-

Another noteworthy issue concerns the question who knew about the Cypriot banks’ exposure to GGBs prior to the PSI agreement in April 2012? The answer is all the more relevant in light of the magnitude of negative consequences affecting the lenders on the island, ultimately resulting in a fifth member of the euro area needing a financial assistance package and the formation of a further troika of international lenders in April 2013.

-

Surely the Bank of Cyprus as supervisory and regulatory authority must have known the state of play. Equally, it would constitute gross negligence, if the Ministry of Finance was not aware of developments and contemplating plan B scenarios post-PSI in Greece. Moreover, Greek banks themselves, with an extensive branch and subsidiary network on the island and deep cross cutting cooperation with Cypriot banks have had at least knowledge of their rivals’ situation.

-

Finally, the Russian authorities understood that something must have been amiss, to say the least. In September 2011 they extended an emergency loan totalling 2.5 billion euros to Cyprus to cover a widening budget deficit and refinance maturing debt. The five-year loan carried an interest rate priced at a rather generous 4.5 percent at the time. The loan was restructured two years later by mutual agreement. It now enables Cyprus to make eight biannual instalments between 2018 and 2021 instead of having to make a full, one-off repayment in 2016. The interest coupon on the loan was also reduced from the initial 4.5 percent to 2.5 percent.

4. Uneven distributional costs – Unbalanced availability of compensation

Let me offer some reflections on the uneven distribution of costs and unbalanced availability of compensation. There are at least four domestic stakeholders that suffered considerable collateral damage, i.e. incurred costs. In three of these cases the costs were not compensated for by either the Greek authorities or the availability of additional financial assistance from international creditors.

a. In the decade leading up to 2010, Greek social security funds were next to domestic banks among the largest investors in the country’s sovereign debt. But the parallels stop there. Whereas four systemic banks were recapitalised following the two debt restructuring exercises of 2012, the social security funds were left to their own devices. They incurred losses totalling 12 billion euros on the write down of their Greek government debt portfolio. This had a direct impact on their ability to pay pensions on time. Furthermore, the regular budgetary adjustments resulting from financing gaps in the social securities’ balance sheet are a recurring bone of contention between the government and the troika of international lenders.

b. The Greek sovereign accumulated in excess of 10 billion euros of payment arrears during 2000-10. One stakeholder affected by this is pharmacists and pharmaceutical companies operating in Greece. These private sector creditors of the government received Greek Government Bonds (GGBs) in lieu of cash payments to cover for some of these accumulated arrears in 2010/11. But when the GGBs were restructured in 2012 there was no compensation available for these holders of sovereign debt. The net effects were company closures and job losses in the sector.

c. A third constituency directly and adversely affected were the more than 15,000 private retail investors in Greece. These citizens, many of whom are pensioners, had decided to invest part or all of their life’s savings in Greek government bonds right up to early 2010. Being told by their bank’s branch manager and receiving reassurances from media coverage that this was a safe investment with regular coupon payments, these investors are today aggrieved, poorer and hold a bag of resentment.

-

Some of these angry private bondholders are former employees of the Greek flagship carrier Olympic Airlines (OA). With the help of their union (OSPA) that are suing National Bank of Greece (NBG). The leading domestic lender was responsible for structuring severance packages for former OA staff. The value of these packages was based on the provision of GGBs that constituted 70 percent of the total severance agreement. After the private sector involvement the value of these packages declined by more than 65 percent.

-

More than 6.000 domestic retail investors in GGBs have formed the Association of Bondholders in Greece. They have teamed up with Greek and international investor rights law firms (e.g. the U.S. based Grant & Eisenhofer (G&E) and Kyros Law to explore the litigation chances of investors pursuing cases both within Greece and abroad (e.g. when the Greek citizen has dual citizenship, see Osborne 2013).

-

These investor disputes will take time to work their way through the judicial complexities of domestic and foreign litigation. But in the meantime, the most precious resource that has been lost for many of these retail investors is the element of a citizen’s trust in public authorities and state institutions. How you regain the invaluable commodity of trust in the state and its financial affairs from these aggrieved citizens turned investors is anybody’s guess.

d. The fourth stakeholder to be added to the cost-benefit analysis of debt restructuring concerns the banks themselves. The need to recapitalise four of the systemically relevant domestic lenders arose from the PSI-related losses and write-offs that banks incurred. Post PSI they had negative capital on their balance sheets. In stark contrast to Ireland, Greek banks did not create the problem (a sovereign debt crisis), but now they owned the problem and its adverse consequences.

-

The major difference to the aforementioned stakeholders incurring sizeable and painful costs rests in the fact that the four banks in question were compensated for these losses.

The issue of burden sharing will continue to take centre stage in any future financial rescue programmes that involves the members of the troika. In particular the IMF is using the lessons learned from the Greek and Cypriot experiences to internally evaluate how bond investors can be brought to share the pain in any future eurozone rescue programme. One option being considered is to impose upfront losses on such investors. However, the Fund itself is quick to underline that its status as a preferred creditor is not affected by such considerations of burden sharing. Put otherwise, its own money as a lender in Europe today is not at stake.

* Jens Bastian is an independent economic and investment analyst for southeast Europe. From 2011 to 2013 he was a member of the European Commission Task Force for Greece in Athens.

[1] See Zettlemeyer, Jeromin, Trebesh, Christoph and Gulati, Mitu: ‘The Greek Debt Restructuring: An Autopsy’, July 2013.

[2] Some inconvenient truths about the German and French crisis narrative on Greece deserve to be remembered, even if revisiting them provides some uncomfortable reading for various banking executives in both countries. In the second quarter of 2010, with the Greek sovereign debt crisis taking center stage in international capital markets French and German banks had more assets invested in Greece than banks from any other country in the eurozone.

The critical question is whether the Greek government has funds to invest and foster growth. This matters more than the math of how high a debt ratio is too high.

The discussion reminds me of the 1980s debt crises starting in Latin America, and the insights provided by Krugman and others then:

http://cliffeconomics.blogspot.com/2013/10/a-second-greek-debt-restructuring-2.html