-

Podcast - How much is Greece getting out of the RRF?

Podcast - How much is Greece getting out of the RRF?

-

Podcast - Between investment grade and rule of law: Greece's contrasting images

Podcast - Between investment grade and rule of law: Greece's contrasting images

-

Where is Greek growth coming from?

Where is Greek growth coming from?

-

Bravo, Bank of Greece

Bravo, Bank of Greece

-

Podcast - A year on from Tempe train crash, trust fades as questions mount

Podcast - A year on from Tempe train crash, trust fades as questions mount

-

Podcast - SYRIZA embraces the chaos

Podcast - SYRIZA embraces the chaos

Which way to the exit?

Kastelorizo had a distinguished guest last week, when Alexis Tsipras became the first prime minister to visit the remote and picturesque Greek island since George Papandreou announced from the same spot almost eight years earlier that he had formally requested the activation of the ad hoc support mechanism the eurozone put together for Greece.

At the time, nobody could have even imagined the dramatic years that followed. Even the most informed participants and organisations involved from the eurozone’s very first programme have been way off the mark throughout a multi-faceted crisis that laid bare all the country’s weaknesses.

Worryingly, as this tumultuous period seems to be coming to an end, with Greece in the final stretch of completing its third programme, the country’s political system remains none the wiser. The same reasons that prevented Greek politicians from identifying the causes that led to the country’s downfall have prompted them to drag the country’s programme exit into the domestic political bear pit.

Alexis Tsipras has every reason to be concerned about ensuring his main legacy will not be what happened in the first half of 2015, when he promised Greeks so much and nearly delivered Grexit.

It is, therefore, crucial for him to get Greece out of the programme and shape a narrative that is based on him delivering on his promise to end the period of strict oversight by the lenders, even with a delay. This is important for his own political survival but also for SYRIZA itself. He is still young and unchallenged within the party and even if SYRIZA loses the next elections, as is most likely, it will probably remain the second main pillar in Greek politics with New Democracy.

Opposition leader Kyriakos Mitsotakis understands that a successful completion of the programme by SYRIZA will allow Tsipras to argue with conviction that it was New Democracy and PASOK that led country into the crisis, while he was the one who took Greece out of it.

This means that an issue which should be entirely technocratic is being approached by the two key players in Greek politics as a deeply political matter, creating unnecessary confusion. The two parties that contributed to undermining any serious debate about the initial causes of the crisis are now having trouble dealing with its conclusion.

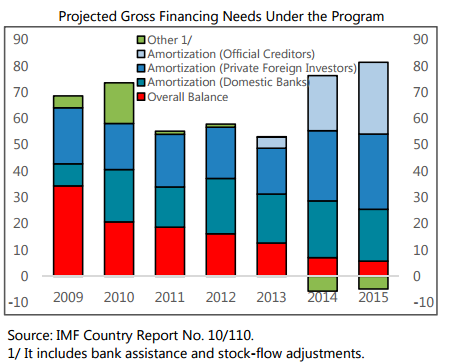

Greece found itself in a desperate situation nearly a decade ago because the New Democracy government in 2009 was caught having lied about the true state of the country’s finances, it was in a nirvana-like state during the 2008 global financial crisis and, in a complete absence of prudent liability management, had allowed debt maturities to pile up during the most turbulent period of recent times in international markets,. Greece needed a total of 170 billion euros over a period of three years to avoid default. Of course, it was shut out of the markets.

It was believed that Greece would be able to stand on its own, without the need of official financing to cover debt servicing and maturities, firstly in 2012, then again in 2015. None of this materialised because the first programme mainly served as a holding operation for the eurozone to firewall Greece and put in place solutions for the sweeping euro crisis. In 2015, Tsipras came to power with a confrontational attitude and the Europeans had failed to deliver on the commitment of debt relief once Greece delivered a fiscal primary surplus.

Returning to its current situation, where Greece is heading after the programme ends will only be decided by the extent to which it can remain solvent without the need for eurozone financing.

Greece cannot be in a programme for ever and there is little desire in any eurozone country to discuss another bailout. The solution devised by Greece and its official creditors in June last summer was to create a safety net of cash large enough to appease the markets and cover Greece’s financing needs for a couple of years after the programme ends.

In an apparent shift of approach to disbursements, which were always released if specific conditions had been met, Greece’s eurozone lenders are disbursing funds for the current programme to cover financing needs beyond August 2018.

Combined with Greece’s own resources from modest bond issues, primary surpluses and privatisations (roughly 1.8 billion in 2018), Greece is expected to accumulate between 17 and 20 billion euros that would allow it to be fully financed until the end of 2019, according to the European Commission’s latest estimates.

If you add to this the latest reforms in centrally managing cash reserves from general government bodies, which stand at 20 billion euros based on the latest data, there is added liquidity to see Greece through well into 2020.

The rationale is that Greece will be conducting bond issues for as long as market conditions remain favourable and rolling over debt maturities. But in the event of market turbulence, the cash buffer will be used to repay debt obligations.

Aside from the mechanics of the post-programme plan, a key factor is how much market access Greece will need.

After nearly a decade of official financing, the PSI in 2012, a debt buyback towards the end of 2012, a swap of the PSI bonds at the end of last year and the short-term debt relief measures that the European Stability Mechanism implemented last year, the market access that Greece needs soon after the programme ends is low.

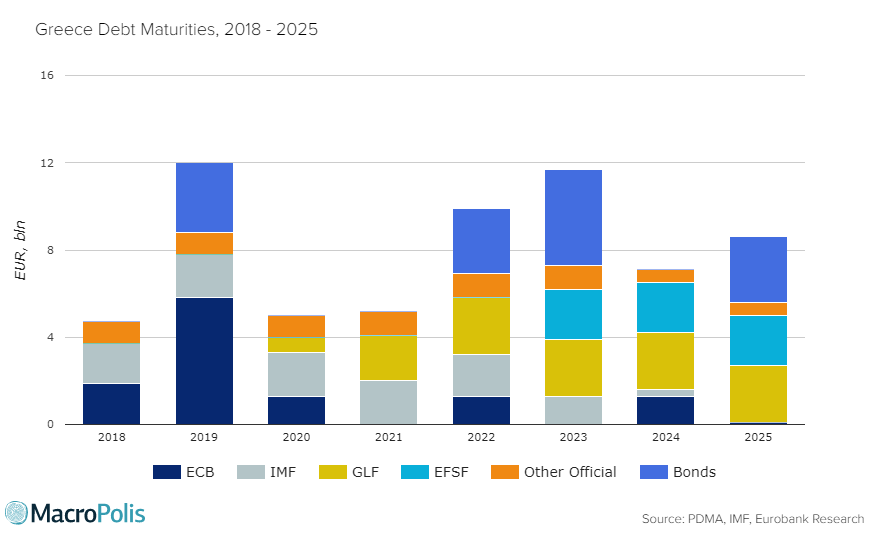

In fact, in 2019 and 2020 it is mostly debt in the hands of the official sector (bonds held by the Eurosystem and IMF loans) that is due to mature.

In 2019, out of 12 billion euros of debt maturities, only 3.2 billion is held by the private sector, mostly from a bond that was issued in 2014 and was partly swapped. It is not until 2022 that the next privately-held debt matures in the form a 3-billion-euro bond issued last summer.

In 2020, on top of the Eurosystem and IMF debt obligations, the repayments of bilateral loans from the first programme start kicking in. The repayment triples in 2021 from 700 million to 2.1 billion.

Out of the total of nearly 44 billion euros of debt maturities in the first five years just 10.6 billion is held by the private sector. As things stand, total financing needs for debt between 2019 and 2021 are just over 22 billion.

Despite that, even according to the current debt profile, Greece is adequately cushioned if there is any market turbulence. Financing needs can be reduced even further, stretching the capacity of the cash buffer.

For the first time at the Eurogroup of May 2016, then re-affirmed at last June’s Eurogroup, it was agreed that programme financing could be used for liability management to prepay other more expensive official creditors, with the IMF being a prime candidate.

The IMF is one of the primary official creditors between 2019 and 2024, with loan repayments amounting to almost 10 billion euros.

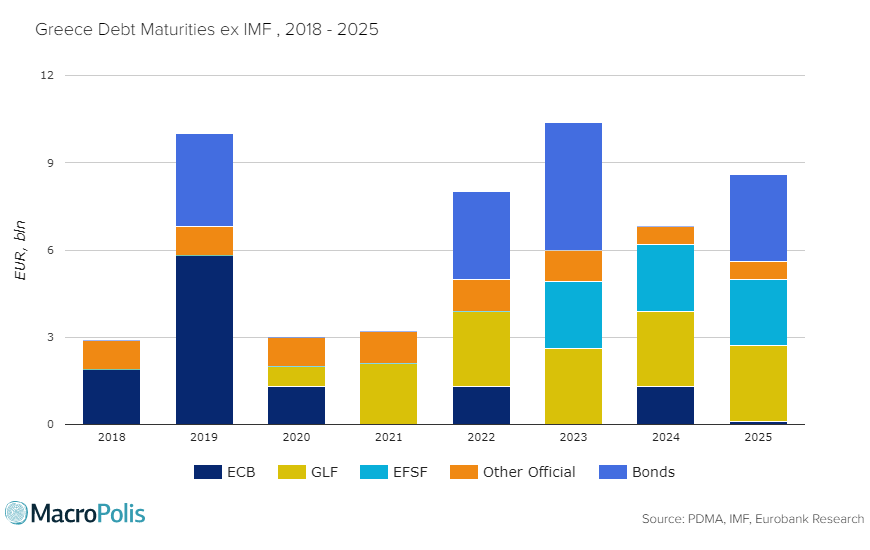

There is ample funding available in the current programme to prepay these loans, all or in part. According to the latest compliance report, it is assumed that 27.4 billion will be unused. If the IMF is removed from the picture, debt maturities up to 2025 barely exceed 10 billion euros annually, with the figure in 2020 and 2021 as low as 3 billion euros.

It worth noting that Greece has committed to significantly high primary surpluses of 3.5 percent up to 2022, which translate into a figure of over 6 billion euros that comfortably covers interest payments.

Without the IMF, Greece’s cash buffer would last as far as the summer of 2022, almost 4 years since the programme’s conclusion forming a rather strong safety net that gives a vote of confidence to the post-programme strategy.

Clearly, after nearly a decade that has been so emotionally charged it is not easy to switch to a pragmatic outlook, a quality that is in short supply in the Greek public discourse at the best of times. However, when the politics and each party’s motivations are stripped away, for the first time there is a clear path that allows Greece to finally stand on its feet again rather than face another false dawn.

*You can follow Yiannis on Twitter: @YiannisMouzakis

If Greece borrows 20 BEUR in order to build up a cushion of 20 BEUR, it pays interest on the borrowing and earns interest on the cushion. My guess is that the difference will be a negative spread of at least 2%. 2% negative spread on 20 BEUR corresponds to a 'cushion-cost' of 400 MEUR annually.

If, instead, Greece were to continue to "rely on its European partners", it would only borrow and pay interest on that borrowing when it needs the money. And the interest would be at least 2% less than what Greece would be paying in the cushion alternative. The political price for saving 400 MEUR annually each year would, of course, be a 4th program.

It may be dumb politically, but personally I would rather negotiate excellent terms for a 4th program and save 400 MEUR annually to spend them on more meaningful things than interest. Particularly in view of the fact that, 4th program or not, there will be some form of EU supervision as long as the EU has loans out to Greece (a century ago, the International Financial Control, the IFC, which was established in 1897, stayed in Greece for almost 40 years, until 1936, and it was finally abolished only in 1975). This gives an idea how long the EU will 'control' Greece.