-

Podcast - How much is Greece getting out of the RRF?

Podcast - How much is Greece getting out of the RRF?

-

Podcast - Between investment grade and rule of law: Greece's contrasting images

Podcast - Between investment grade and rule of law: Greece's contrasting images

-

Where is Greek growth coming from?

Where is Greek growth coming from?

-

Bravo, Bank of Greece

Bravo, Bank of Greece

-

Podcast - A year on from Tempe train crash, trust fades as questions mount

Podcast - A year on from Tempe train crash, trust fades as questions mount

-

Podcast - SYRIZA embraces the chaos

Podcast - SYRIZA embraces the chaos

Going for Growth: What next for Greece's economy and banks?

A decade on from the global financial crisis that led to Greece enduring painful austerity and an asset base collapse, the country is on a gradual road to recovery. This was reflected by record tourism numbers in 2018 - some 30 million visitors who between them spent 16.1 billion euros[1]. And yet with 18.6 percent unemployment[2], millions of Greeks still don’t have work or a path to a better life.

To give a clearer idea of what the country has been through, GDP in 2007 was 318.9 billion dollars and the GDP per capita was 28,900 dollars[3]. In Q4 2018, those figures stood at 218 billion dollars and 20,311 dollars - entailing declines of 33 percent and 29.7 percent respectively – according to figures published by the IMF[4].

In the same figures, the IMF foresees increasing growth for the economy over the coming two years, but nothing like the numbers of the past. Indeed, residential property trades at a -46.3 percent real terms discount from its peak[5] and the sector can only recover in the coming years, which is a source for optimism.

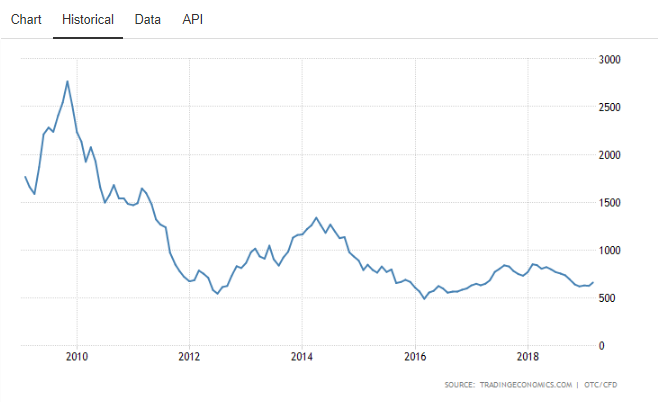

But all those numbers crucially hide changes in the cost of living, equity values falling off of a cliff, and a national brain drain of emigrating young Greeks – damaging outcomes. Listed and unlisted firms have also been particularly hit, with a series of capital market suspensions and a stock market that has contracted by 83 pct (figure 1), a staggering figure.

Figure 1: Greek Stock Market Capitalisation

Few will shed a tear for the plight of businesses and their values, but the ability to grow an economy out of a crisis - especially when the currency isn’t controlled at a domestic level – is made so much harder when the intrinsic value of listed firms is diminished.

Furthermore, when the Greek government took the step to close financial markets and banks in 2015[6] an additional spotlight was shone not just on the impact of equity income - important for pension funds – and personal wealth, but on the reliance on small group of firms at the top, particularly banks[7].

However, there are of course sources of optimism and opportunity, and in many senses the story of Greece, and its economy, have gotten lost in a decade of economic negativity, fears on currency default, and political risk. But it is the future of the Greek economy which is far more interesting and exciting to people of Greece, international investors, and businesses in the country.

Growth and Internationalisation: The Path Forward

As an economy, Greece’s is pretty easy to understand with agriculture, tourism, shipping, petroleum exports, and services dominating. And despite a Financial Times article in 2018[8] that stated that some 40 percent of firms have failed to innovate, grow, and are effectively in “zombie” status since the crisis, the remainder where on a much better footing. In terms of inward foreign direct investment (FDI), record inflows of capital have entered the country (figure 2) which is a positive sign of encouraging growth, with money going into tourism, tourism schemes[9], logistics, financial services, and real estate.

Figure 2: Source: Bank of Greece

FDI investment isn’t surprising considering the cheap price of various assets, lack of domestic liquidity for financing investment, and a successful start-up and tech scene which has raised 250 million euros of venture capital and witnessed a number of exits[10]. That said, however, outward FDI – investments made by Greek firms abroad – have been miniscule by comparison, as disclosed by the OECD[11], and this is one the clearest problems for the country, it’s economy, and its banks.

If Greece is to turn its economy around, grow, and still be owned by Greek investors and companies that are domiciled in the country at the end of it, then international expansion and growth is vital not only for balance of payments and foreign exchange – i.e. bringing profits homes - but to increase output, the size of firms, and ensure economic diversification occurs.

Perhaps the services sector is the ripest opportunity for expansion and growth, not just through M&A, but via less expensive joint ventures and partnerships – when was the last time you heard of a Greek management consultancy firm or insurance company beyond regional operations (sorry Hellas Direct)? And yet a bank like Santander has global operations and reputation, despite its fledgling beginnings.

Moreover, if the country put its mind to it, then it could develop successful private banking and asset management sectors, both underdeveloped at present when one considers that Greece presently has 52 asset management firms compared to over 1,000 for the UK and 120 for the fairer comparable of Malta[12].

If growth is the medicine to end austerity and improve wealth, then how can Greece be so amazing at marketing itself to tourists to visit/fall in love with it, and yet only have one decent sized domestic airline Aegean Airlines, and one realistic emerging challenger in Ellinair? Further, for all those marketing skills and branding capabilities, communications and marketing agencies could be better at exporting what they do and how they do it to other European and Middle Eastern markets.

Equally, Greece could without too much thought, conceivably become a global player in renewable energy – with 130 wind firms in development - environmental technology, the experience economy, eco-tourism, and yacht building – all areas that play to geographical, cultural, environmental, and sectoral strengths. Green energy would also move the country away from expensive oil imports and a reliance on coal.

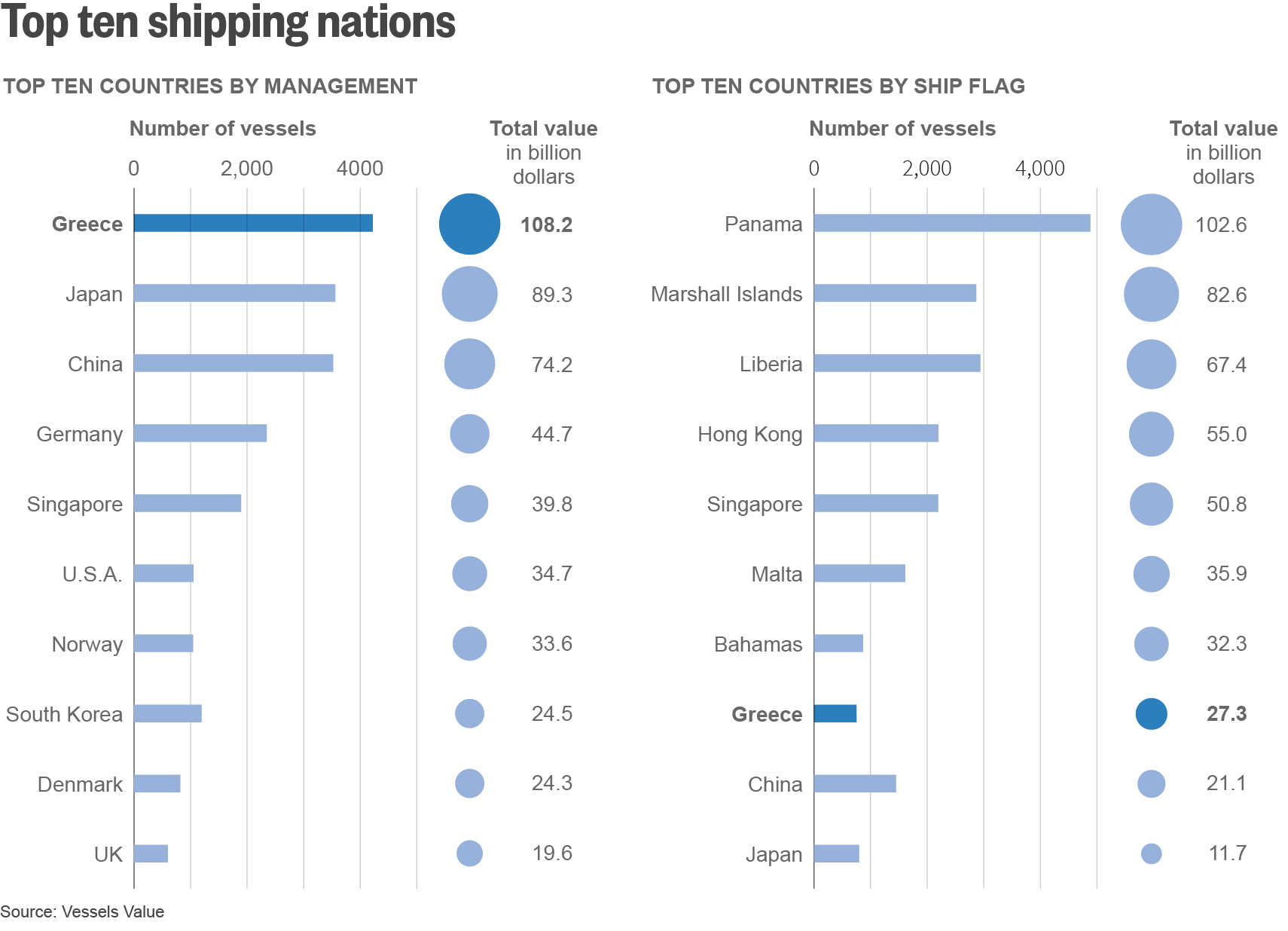

Even in merchant shipping, a sector dominated by Greece, opportunities for growth are being missed. Firstly, Greek shipping firms pay no direct tax to the public purse. Secondly, despite the largest fleet by tonnage in the world (figure 3), so called ‘flags of convenience’ ensure that Greece isn’t benefiting from the international aspect of the global positon it holds, when it should be viewed in the same way English football and American tech firms are: as international flag bearers.

In addition, there is a notable absence, in that for all of the merchant shipping that Greece is directly and indirectly involved with, it doesn’t have a single standalone merchant bank – let that sink in.

As Tom Bergin’s Reuters article The Greek Shipping Myth[13] establishes, the shipping sector is not contributing as much as in reality as it proclaims to be. But reshoring the sector, and the shipping families that run it, need not be an adversarial process, instead a way to take the industry forward for the good of Greece, in spite of slowing trade of goods, and the lease of ports to the Chinese.

Figure 3: Originally Published by Bloomberg

Banks have a vital role to play

Despite the desire of Greek banks to deleverage their books and rid themselves of bad loans, there is a need to facilitate the international expansion of Greek firms and take on debt elsewhere. In that respect, Greece needs to utilise the banks that dominate the economy - Alpha Bank, Eurobank Ergasias, National Bank of Greece, and Piraeus Bank - as well as smaller banks including: Attica and Praxia, to make this happen.

Yes, Greek banks have been burnt by non-performing loans, over-exposure, and loose fractional reserve lending, but so have Italian banks, and if you look deep enough so are other banks in the eurozone, which is catching up with them as shed thousands of jobs, peel back operations, and divest from countries and offerings.

To that end, and with Greece in mind, it is also fair to say that countries have to move on and become ambitious again – look at post-war Germany and Japan, and South Korea’s development in the decades following the Korean War; Britain in the 1990s and 2000s. Greece has do the same because although the domestic economy will get stronger and grow larger, the opportunities outside of Greece are numerous.

Naturally, doing this to an economy is not without risk, but doing too little or nothing to encourage international expansion and growth, is just as risky in a world where disruption and M&A are key components of strategy that risks leaving some countries and their economies behind.

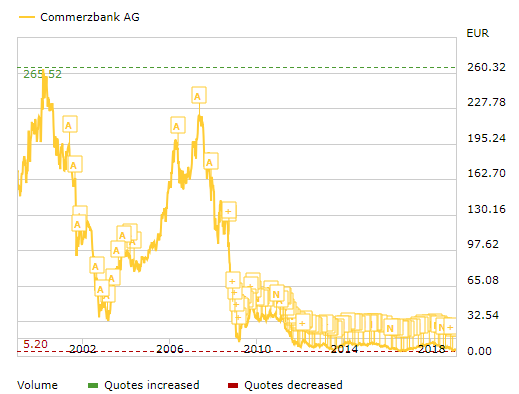

Equally, for humbled Greek banks operating in a post-crisis world, they can take stock that even in an export-led, fiscally abundant, and saver-led economy such as Germany, its two biggest banks - Deutsch and Commerzbank – are constantly encircled by problems.

Deutsch’s woes stem from growing too large, and for too often being in the news for wrong reasons – scandal, management changes, layoffs, and strategic change – as the Financial Times covered so fantastically in 2017 article[14] How Deutsche Bank’s high-stakes gamble went wrong - the problems are the same now as they were then. In fact, Deutsch’s share price was 112 euros per share in May 2007, at the end of February those same shares were worth 7.78 euros – horrible numbers.

Commerzbank’s numbers are even worse, with its share price in May 2007 being 215 euros per share, yet that number stands at 6.78 as recently as February 26 (figure 4)[15].

Figure 4: Commerzbank Share Price

And because Greece’s banks have experienced the same fall from grace, they, and the government which should utilise them for newer ends, should know that they are not alone.

The point is that, that firms like Anek Lines SA (passenger shipping) and J&P-Avax SA (construction), as just two examples, need to increase the amount of business they do abroad, in particular, where they do it. Greek banks need to offer that finance, aid those expansion, and grow themselves.

The Greek economy, and the Greek government which leads, diversification, expansion, and opportunity are there for the taking as long as it is undertaken in a meaningful, measured, and planned way. The path forward can be great for Greece, its economy, companies, and people, as well those investors that back them, so taking a leap is a natural step ahead as the fundamentals and the opportunities are there.

*Robert is an investment and strategy consultant, and a trade consultant to Export Action Global. He writes about business strategy, international finance, and geopolitics.You can follow him on Twitter: @RobertQJaneiro

[1] https://greece.greekreporter.com/2019/02/22/tourism-sees-record-year-as-over-30-million-visit-greece-in-2018/

[2] https://neoskosmos.com/en/128549/greece-noted-the-biggest-drop-in-unemployment-but-still-highest-in-europe/

[4] https://en.portal.santandertrade.com/analyse-markets/greece/economic-political-outline?&actualiser_id_banque=oui&id_banque=44&memoriser_choix=memoriser

[6] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-07-07/greek-stock-market-suspended-for-two-more-days-amid-bank-closure

[9] https://www.hospitalityireland.com/greece-gives-green-light-three-tourism-investment-schemes/71411