-

Podcast - How much is Greece getting out of the RRF?

Podcast - How much is Greece getting out of the RRF?

-

Podcast - Between investment grade and rule of law: Greece's contrasting images

Podcast - Between investment grade and rule of law: Greece's contrasting images

-

Where is Greek growth coming from?

Where is Greek growth coming from?

-

Bravo, Bank of Greece

Bravo, Bank of Greece

-

Podcast - A year on from Tempe train crash, trust fades as questions mount

Podcast - A year on from Tempe train crash, trust fades as questions mount

-

Podcast - SYRIZA embraces the chaos

Podcast - SYRIZA embraces the chaos

Losing game: Another doomed effort to revive Greek football?

Greek football, as a sporting spectacle or cultural experience, died many years ago. But its lifeless body is being dragged through the streets of Athens, Piraeus and Thessaloniki again.

The Greek government signed this week an accord with European football’s governing body, UEFA, aiming to restore a semblance of respectability to the sport. This is not the first time Greek authorities have turned to outsiders for help. New Democracy’s predecessors did the same and there were others before that.

Each time it has resulted in little more than lip service and some cosmetic changes. The rotten core of Greek football has remained untouched because nobody has the guts to change anything or feels there is enough to gain from disturbing the status quo.

Too many football club owners in Greece see the sport as a vehicle for wielding power and advancing their business or political interests. Too many politicians are content to kowtow to these strongmen in the hope that their influence over hardcore groups of fanatical supporters, loyal armies essentially, can serve political ends or at least not be turned against parties or governments.

This nexus has become harder to break as the years have rolled by and fans have deserted the game due to the lack of quality on the pitch, decent conditions off the field and any sense of fair competition in general. Between 2010 and 2017, average attendance in the Greek Super League almost halved to around 3,500. There was a slight increase last year, possibly boosted by the title-clinching run by Thessaloniki club PAOK, which became the first team outside of Athens to win the championship since 1988, which was, incidentally, the last time that average attendances in Greece reached five figures (11,256).

“The number of people making their way to football stadiums to support their team remains an important indicator of the health of club football,” says UEFA in the latest version of its annual benchmarking report. In Greece, attendance figures show that club football is flatlining. The absence of fans has also removed any possibility of a grassroots revolution against the sport’s debasement.

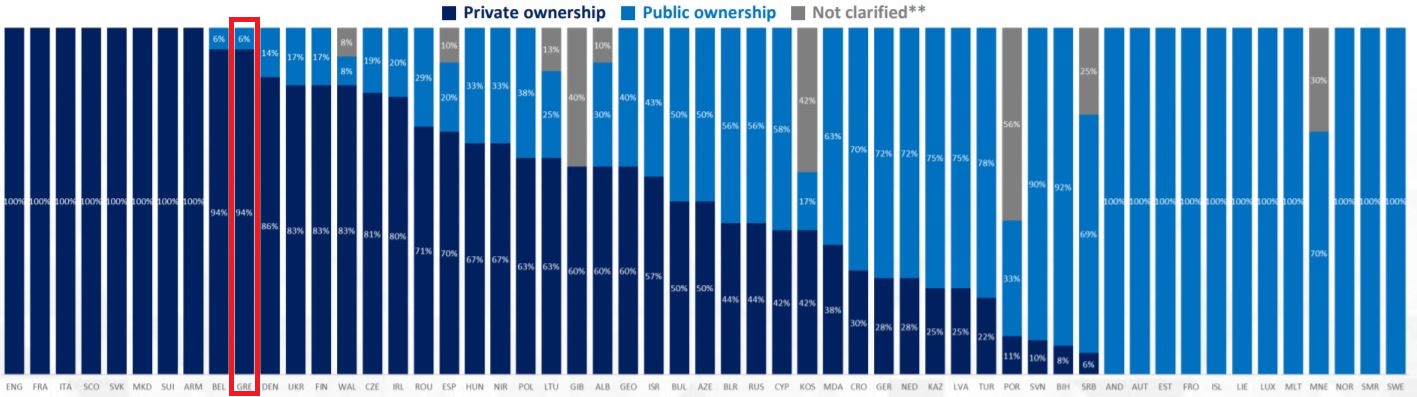

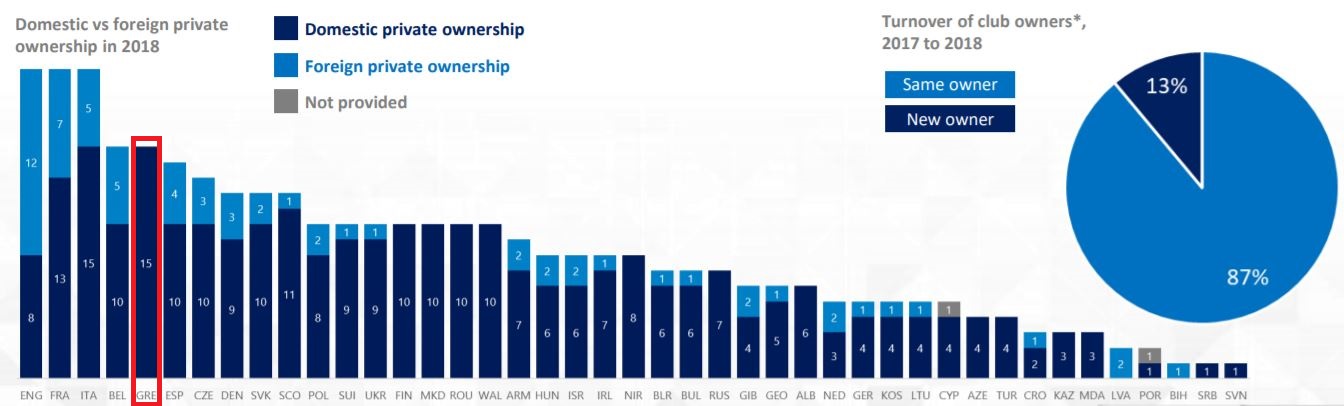

The departing supporters have left politicians and tycoons to their playthings – Greece’s leading clubs are, on average, 94 percent privately owned, bucking the trend in Europe, where last year there were 28 countries in which at least half of all top division clubs were owned by private entities or individuals, and eight where all clubs were privately owned.

Greece also has one of the few top-flight leagues in Europe where there is no foreign ownership of clubs, underlining that it is a closed shop. Introducing best practices from abroad would be an annoyance for all those involved in Greek football, but equally no investor in their right mind would consider a local club to be an attractive option.

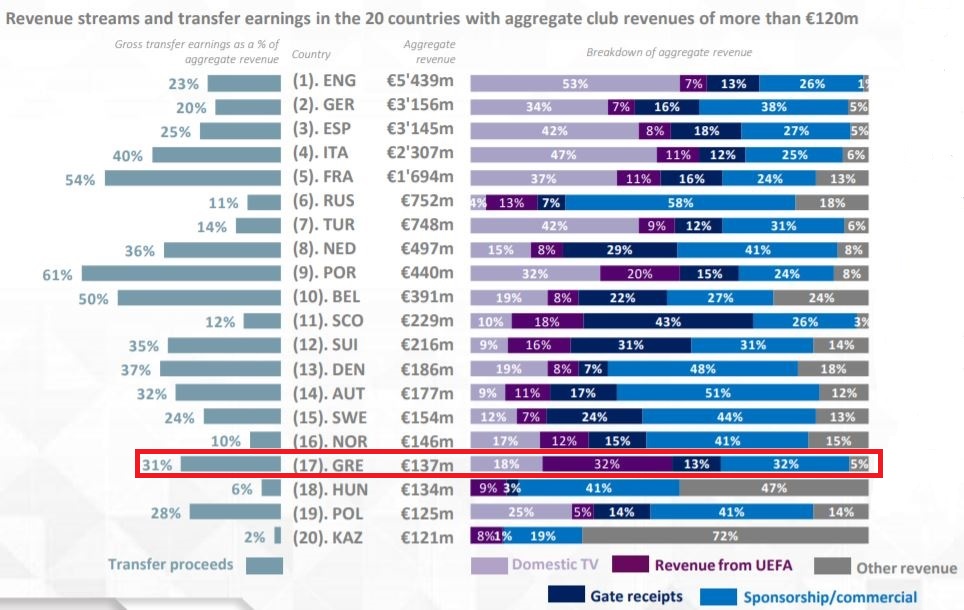

According to UEFA, Greece’s top division clubs generated 137 million euros in revenue in 2018, which was on a par with Poland and Hungary but below countries like Norway, Sweden, Denmark and Austria. Notably, it was less than a third of the 440 million euros generated by Portugal’s first division teams.

For Greek clubs, 13 percent of this income came from gate receipts, which is one of the lowest proportions in the top 20 revenue-earning European leagues. The Greek league is also more reliant than any other from this group on revenue from UEFA.

In terms of sponsorship and commercial revenue, Greek clubs earned an average of 2.8 million euros in 2019, which was 19th out of the top 20 leagues, highlighting the difficulties they have in convincing businesses to associate themselves with the sport.

Eighteen percent of the revenue earned by Greek clubs comes from TV rights. But the fare being served up is so poor the previous government had to step in two years ago to offer seven Super League clubs that had no TV deal a two-year contract with public broadcaster ERT. Soon after coming to power, New Democracy announced that it would reduce the money being paid for the clubs’ games because ERT could not afford it.

In short, Greek football clubs tend to be poorly run as businesses, offering meagre entertainment to fans and viewers, and often rely on the state to prop them up. It is no wonder fans are turning their backs and few in Greece, and nobody outside the country, sees a reason to invest in the sport.

Bleak history

“I hope Greece becomes again one of the top countries, like in 2004 when it won the Euro,” UEFA President Aleksander Ceferin told Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis this week when they met to agree that the European governing body would draw up a roadmap for Greek football over the next three months.

It is understandable that Ceferin would want to inject some optimism into the situation, but the Greek national team’s Euro 2004 victory, when it upset all the odds and far more powerful rivals to lift the trophy in Portugal, was an anomaly in more than just footballing terms.

A foreign coach, Otto Rehhagel, who was impervious to the poison flowing in the Greek game galvanised a squad of players, a third of whom were playing abroad, for one glorious push after mustering all his experience, nous and a dose of good fortune. Had Greece’s domestic football been in a respectable state, Rehhagel’s team would not have been given odds of as much as 150-1 to lift the trophy, making it one of the biggest sporting upsets of all time.

One could debate whether Greek football is in a worse state now than in 2004 due to the presence of more, and brasher, oligarchs, but we would only be musing over the levels of rot. A new book called Sports and Social Resistance written by journalist Nassos Bratsos traces how football has been dogged by political interference and exploitation since the 1930s, when dictator Ioannis Metaxas ruled Greece.

“The popularity of sport was a magnet for political intervention, often by authoritarian regimes, and its mass appeal created the possibility for there to be resistance to these choices,” Bratsos told Greek investigative new website Inside Story recently.

The appetite for resistance no longer seems to exist, though. The chairmen of big clubs in Greece are often media owners as well, using their outlets to cultivate blind fanaticism rather than a love of the game. Anyone who genuinely loves football wants nothing to do with this diseased environment, turning instead to the amateur version of the sport, which is not free of problems but can at least provide a sense of connection and where some academies and coaches are doing admirable work in trying to instil values in young players as an antidote to the toxicity in the professional game.

The other option for football lovers is to follow the foreign leagues. Today, Greek children are far likelier to know more details about teams and players abroad than they do about those on their own doorsteps.

Shifting the goalposts

The lifeblood of the game is being cut off but few of those involved seem particularly bothered about what this bodes for the future. The government will point to its efforts to draft in UEFA’s assistance to draw up a “memorandum” to fix Greek football. As mentioned, we have been down this road before and little changed. Also, this appeal to a higher (and foreign) power rings hollow after the centre-right administration recently surrendered an opportunity to impose order in the game.

New Democracy passed through Parliament in January a hastily drafted amendment to prevent two clubs, PAOK and Xanthi, from being relegated after the Professional Sports Committee deemed that the two teams had ownership links, which are not permitted. Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis said his administration stepped in to prevent “social cohesion” in Greece being disrupted after PAOK fans reacted angrily to the panel’s verdict, attacking the offices of some conservative MPs and threatening further protests.

The government’s amendment sparked an angry reaction from Olympiakos fans and officials, putting the government at the centre of a public clash between the Piraeus club and its fierce rival, PAOK. Many in Greece saw this dispute as a proxy war between the club’s two owners.

It is telling that the government, like many of its predecessors, feared that social cohesion in Greece was more at risk from angry fans than the absence of a clear set of rules for participants and penalties for anyone who breaks them.

It was confirmation that nothing has changed in the last decades. In 1988, supporters of Thessaly club Larissa took to the streets and cut off traffic on the Athens-Thessaloniki highway, to protest the decision to deduct four points from their team after one of its players failed a doping test. At that point, Larissa were on their way to a first, and most unlikely, title win in Greece’s top division. Following the uproar, the then PASOK government changed the law to ensure that the club from Greece’s rural heartland would not be docked points.

The government's decision this January further undermined people's trust in the game, its ruling bodies and the state's ability to create a level playing field, compounding the lack of trust in decision makers and institutions that is endemic in Greek society. The rushed amendment had not even passed through Parliament when fans of other clubs that had been penalised in the past called for those decisions to be overturned.

The irony is that in changing the rules, the government did exactly what New Democracy MEP, former PAOK player and chairman, Theodoros Zagorakis had demanded a few days earlier. Zagorakis, who showed that his allegiance to his former club was stronger than to his political party or to the country's laws, decried the sports commission's verdict and suggested foul play by PAOK's rivals was involved. He was summarily ousted from New Democracy for his outspoken reaction, but the centre-right government ended up satisfying the demands he, and thousands of PAOK fans, made just days later.

“Power, authority, threats and violence have acquired squads, built stadiums and ordained results,” writes David Goldblatt in "The Ball is Round," his authoritative history of football around the world. “Football has served the greater glories and fed on the brute power of every imaginable political institution; all to borrow or steal their share of glory.”

It is a reminder that the afflictions undermining Greek football have been encountered elsewhere, and are still causing problems in some parts of the world. But when one looks at the state of the Greek game today and compares it to most places in Europe, it seems that while others may be suffering, football in Greece has long succumbed to its illness.

*You can follow Nick on Twitter: @NickMalkoutzis