-

Another crisis chapter closes, triggering final round of debt relief measures

Another crisis chapter closes, triggering final round of debt relief measures

-

Exit from enhanced surveillance nears, but fiscal commitments bind Greece until 2060

Exit from enhanced surveillance nears, but fiscal commitments bind Greece until 2060

-

Enhanced surveillance concludes, but more reforms and tougher fiscal targets lie ahead

Enhanced surveillance concludes, but more reforms and tougher fiscal targets lie ahead

-

Some tasks, risks left as Greece takes another step to exit from post-bailout surveillance

Some tasks, risks left as Greece takes another step to exit from post-bailout surveillance

-

Latest EC review clears path towards end of enhanced surveillance process in 2022

Latest EC review clears path towards end of enhanced surveillance process in 2022

-

Creditors give thumbs up for 10th post-MoU review, underline pandemic legacy

Creditors give thumbs up for 10th post-MoU review, underline pandemic legacy

IMF sets out why it stands apart from eurozone on long-term growth prospects

Greece’s long-term growth potential was one of the main points of contention as the International Monetary Fund and the Greece’s eurozone creditors were attempting to bridge their differences on debt sustainability to ensure the conclusion of the review and the Fund’s participation in the programme.

In the official document setting out the Precautionary Stand-By Arrangement that was finally agreed at the June 15 Eurogroup, the Fund dedicates a section in which it outlines in detail its rationale for its conservative projections regarding Greece’s long-term growth prospects.

The country’s demographics and its productivity record lead to a rather pessimistic outlook with limited scope for growth, which the IMF does not see exceeding 1 percent over the next half-century even if structural reforms deliver payoffs in areas of weakness.

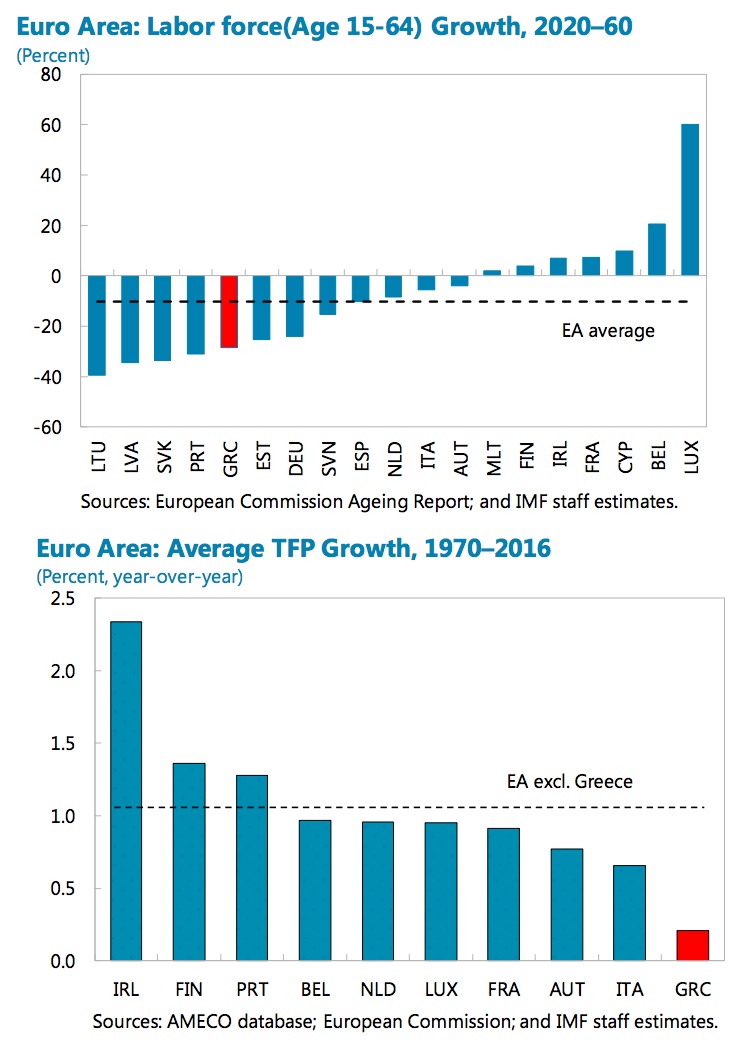

Over the next decades, which form the timeframe that the IMF and the Eurozone have to agree the sustainability of Greece’s debt, Greece is expected to experience dramatic population ageing. The European Commission in its 2015 Ageing Report foresees Greece’s working age population falling by about 30 percent due to a shrinking and rapidly ageing population. The IMF notes that the outward migration of working age population observed during the crisis has the potential to exacerbate those dynamics if the current trend is not reversed.

This anticipated working age population decline is amongst the highest in the euro area and three times the average, which implies an annual reduction of Greece’s labour force just short of 1 percent (0.9 percent) each year over the next five decades.

Greece’s historical productivity growth record amplifies the Fund’s conservative stance on the country’s long-term growth capacity as the low openness of the economy and a large allocation of labour in non-tradable sectors led to an average productivity growth of just 0.2 percent in the last 45 years, by far the lowest in the euroarea and less than 1/5 of the region’s average.

Given this historical record the IMF estimates in steady state a 0.4 percent total factor productivity growth.

Investments are seen giving Greece a short-term boost as they recover from their highly depressed levels but their impact will wane once the stock of capital reaches its long-run level. The investment recovery will lead to real growth rates of over 2 percent, but once this transition is completed the factors that will determine Greece’s growth trajectory will be restricted productivity growth and the highly problematic demographics.

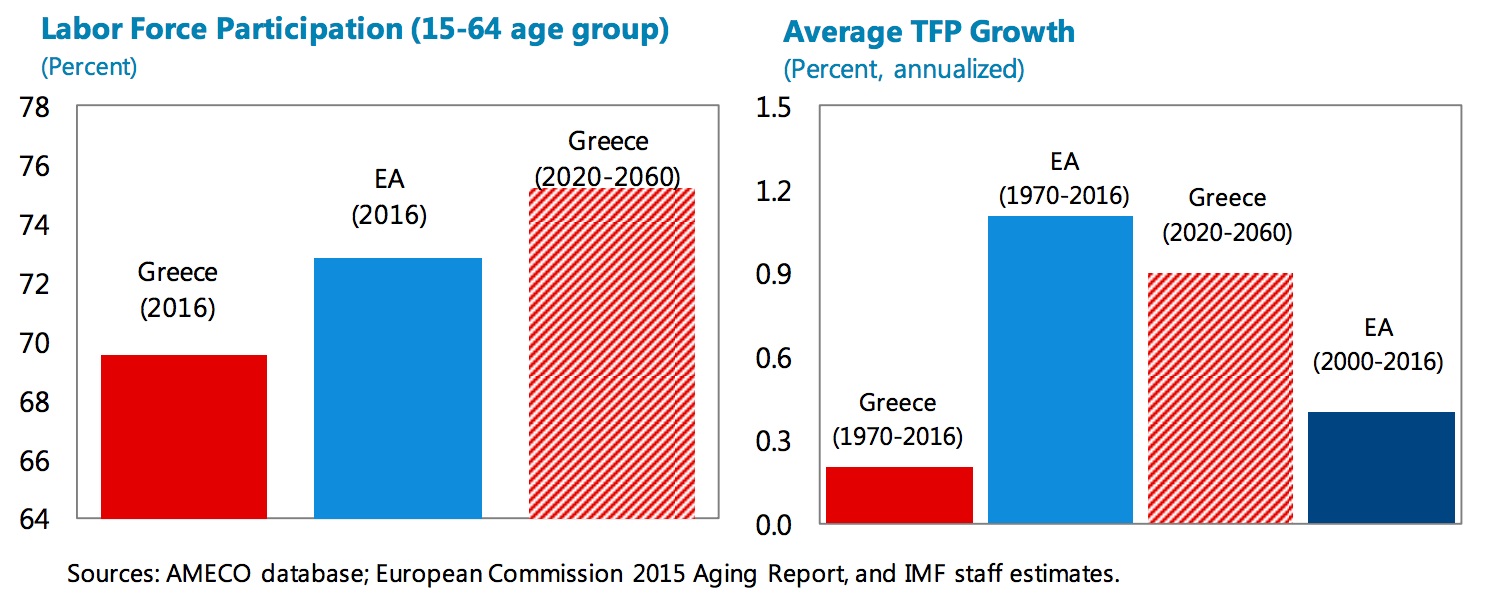

The starting point of the Fund’s assessment of Greece’s long-term growth is a negative 0.5 percent from the combination of 0.4 percent output per worker and the -0.9 percent annual decline of working age population. According to the IMF, recent findings in the literature support its view with the baseline growth rate for Greece, before the effect of reforms, at -0.4 percent during 2024-2043.

Greece will need to rely heavily on reforms that will enhance productivity and employment to reverse this negative trend. However, even in the event of structural reforms endorsement and implementation by the Greek authorities, historical evidence presented by the Fund shows that although reforms in labour and product markets can impact output levels during the initial decade, their effects on growth wane afterwards, Even in the short-term, successful reformers do not have to show growth gains of more than 0.6 percent.

Combining all factors, the impact of structural reforms for Greece will need to reach 1.5 percent annually to offset the -0.5 starting point and achieve even the modest 1 percent growth that the IMF estimates for the next half century.

Estimates by the OECD and in the literature presented in the IMF’s documentation suggest that full reform implementation can enhance annual growth by as much as 1.3 percent but only for the first decade.

The Fund concludes that its 1 percent annual growth assumption requires a profound reform drive both by the authorities and the population that will push Greece’s labour force participation to levels that exceed euro area average and thus offset the significant decline in the working age population. Equally, it will require Greece to generate productivity growth that will enhance its historical record by a substantial margin.

The Fund urges for “rapid and decisive action on the part of the authorities to tackle the many bottlenecks that constrain growth and limit the country’s ability to prosper in the euro area.”

IMF downgrades Greek GDP and unemployment forecasts

IMF downgrades Greek GDP and unemployment forecasts  IMF revises fiscal estimates upward, sees debt ratio at 162.8 pct in 2022

IMF revises fiscal estimates upward, sees debt ratio at 162.8 pct in 2022  IMF approves programme "in principle," repeats position on debt and reforms

IMF approves programme "in principle," repeats position on debt and reforms