-

Inequality rises marginally in 2023, with 1.9 mln Greeks at risk of poverty

Inequality rises marginally in 2023, with 1.9 mln Greeks at risk of poverty

-

Workers lost almost 9 pct of real income last year, research shows

Workers lost almost 9 pct of real income last year, research shows

-

Latest census data shows demographic challenge is here as population shrinks, ages

Latest census data shows demographic challenge is here as population shrinks, ages

-

Risk of poverty drops to 26.3 pct, reflecting post-Covid rebound

Risk of poverty drops to 26.3 pct, reflecting post-Covid rebound

-

Poverty rate rises in 2021; even after social transfers 1 in 4 children are at risk

Poverty rate rises in 2021; even after social transfers 1 in 4 children are at risk

-

From the National Energy and Climate Plan to COP26: What has Greek climate policy learned?

From the National Energy and Climate Plan to COP26: What has Greek climate policy learned?

Could Greece's immigration reforms have an impact on upcoming elections?

Debate around a recent amendment to Greece’s Citizenship Code has prompted a flurry of claims linking the granting of Greek citizenship to upcoming electoral contests.

The right-wing press and the opposition have accused the government of seeking to change the composition of the electorate in key districts by easing the path to citizenship for foreign nationals at a key time in the election cycle.

While these citizenship-for-votes claims have been categorically denied by the government, they strike a chord with a Greek public that has become increasingly xenophobic and suspicious of immigrants in recent years. As Greece enters a prolonged campaigning period, with local and European elections coming in May and national elections sometime before the end of the year, issues that touch on national identity are shaping up to become the focus of intense and acrimonious debate.

Accusations and rebuttals

On the eve of new legislation on the granting of Greek citizenship, several pointed questions were raised by opposition MPs around the number of new citizenships and their implications for the electoral map.

In a parliamentary question, New Democracy’s shadow defence spokesman Vassilis Kikilias cited a front-page article in right-wing Estia newspaper, claiming that “the government has added 43,000 foreign voters to the electoral register for the Athens A’ district, while it steadfastly refuses to give the vote to expatriate Greeks.” The article linked forthcoming legislation to promote so-called “express citizenship procedures” to the upcoming local, European and national elections, pointing out that SYRIZA had gained 78,431 votes in the district in question in the last general election, a very narrow lead over New Democracy’s 77,630 votes.

Another New Democracy MP, immigration spokesman Miltiadis Varvitsiotis, queried the 136.9 percent increase in successful citizenship applications in the three years to 2017. Varvitsiotis noted that the largest increase was recorded between 2015 and 2016, near the start of SYRIZA’s term in government, when the number of citizenships granted “skyrocketed” from 14,178 to 33,487.

Interior Minister Alexis Haritsis responded by describing the claims as a “far-right conspiracy theory, entirely constructed out of fake news, xenophobia and racism”. He cited ministry figures showing that 12,841 foreign nationals acquired Greek citizenship in the Athens A’ district between 2015 and 2018 by meeting the legal requirements.

The minister noted that the majority of those cases relate to second-generation immigrants born in Greece and attending Greek schools, as a result of legislation introduced by his government in 2015.

New Democracy are not the only mainstream political party to express alarm over the recent increase in successful citizenship applications. Earlier last year, Giorgos Tsaousis, an immigration lawyer and migration spokesman for centrist party To Potami, had criticised the discretionary nature of citizenship panels, which he blamed for an unaccountable increase in citizenships granted to naturalised foreign-born applicants. These increased from 1,487 in 2015 to 3,483 in 2017.

Some of the accusations levelled at the SYRIZA government, meanwhile, stray into more sinister territory.

In a much-discussed recent tweet, Niki Tzavella, a New Democracy candidate for the European Parliament, claimed that “her Afghan greengrocer” was receiving text “in Afghan” (sic) telling him to vote for SYRIZA, and that “the Pakistanis are receiving similar messages in Pakistani” (sic). “Very interesting elections!!”, she concluded.

In a similar vein, commenting on a video of a meeting between Migration Policy minister Dimitris Vitsas and representatives of the Pakistani community in Athens, New Democracy’s Varvitsiotis accused Vitsas of “shamelessly bragging in front of the Pakistani community of legislation voted in by his government which allows anyone, with any kind of paper, even a letter, to apply for a three-year residence permit.”

Paraphrasing a SYRIZA slogan used by the minister, “dreams don’t have borders”, Varvitsiotis rejoindered that, “sadly, the dreams of SYRIZA are proving a nightmare for Greeks.”

The long-standing accusation that the governing party maintains an “open door” policy to migrants looks likely to gain greater urgency in view of the forthcoming elections, so it is worth examining whether there is any substance to this latest wave of allegations.

Recent changes

There have been two major changes to immigration law since SYRIZA came to power in 2015. Law 4332/2015, passed in July 2015, eased the path for children of foreign parents born and/or educated in Greece to become citizens. This law revived, in slightly amended form, legislation previously passed in 2010 by the PASOK government of George Papandreou (law 3838/2010, the so-called “Ragousis law”), which had been overturned on constitutional grounds by the Council of State. The successful implementation of the law marked a major change, which opened a new path to citizenship for large numbers of long-term foreign residents of Greece.

The most recent legislation, law 4604/2019, passed on March 20, contains a series of amendments to the Greek Citizenship Code designed primarily to meet Greece’s obligations as a signatory of the UN Convention on Human Rights. These include designating paths to citizenship for older applicants and the disabled, as well as for stateless Roma who have a historical presence in the country. It also replaces the citizenship interview with a standardised citizenship test, shortens the process, and reduces the fees for the citizenship application from 700 to 550 euros.

In addition to the legislation currently in place, SYRIZA is proposing, as part of the ongoing debate on constitutional reform, to allow foreign nationals permanently resident in Greece to vote and stand for office in local elections.

What the numbers say

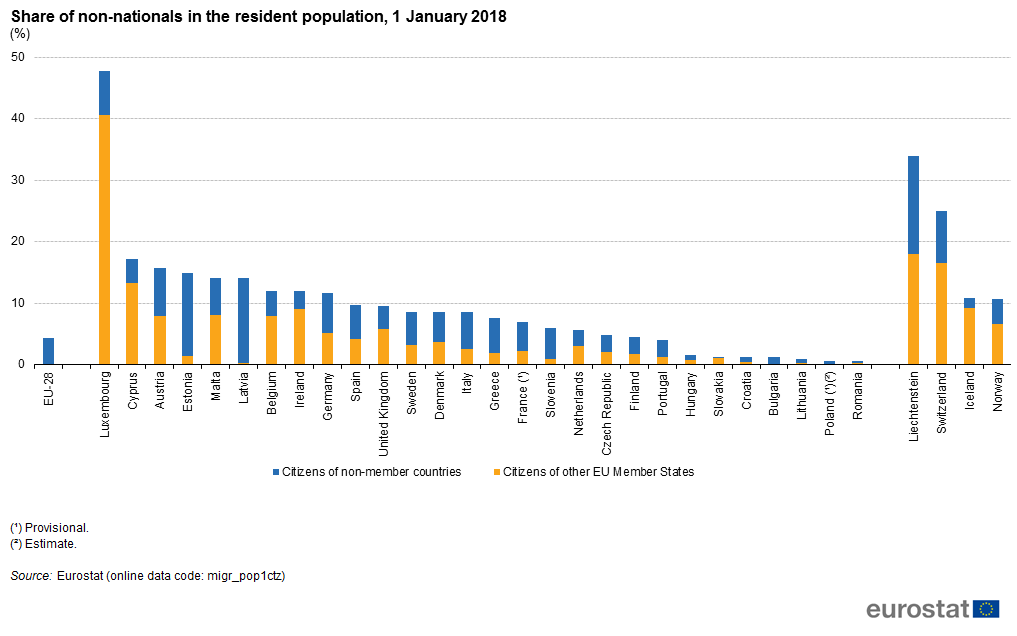

The potential pool of new citizens was and is substantial. The 2011 census counted 912,000 foreign nationals permanently residing in Greece , close to 8.5 percent of the total resident population at the time. More than half were Albanian citizens (52.7 percent, followed by Bulgarians at 8.3 percent and Romanians at 5.1 percent). The portion of non-citizens in the general population has remained fairly stable. Eurostat figures show that Greece is currently home to around twice the European average of resident foreign citizens relative to the total population, however it ranks below most member-states including similarly sized countries like Austria and Belgium. The majority foreign nationals in Greece originate in non-EU states.

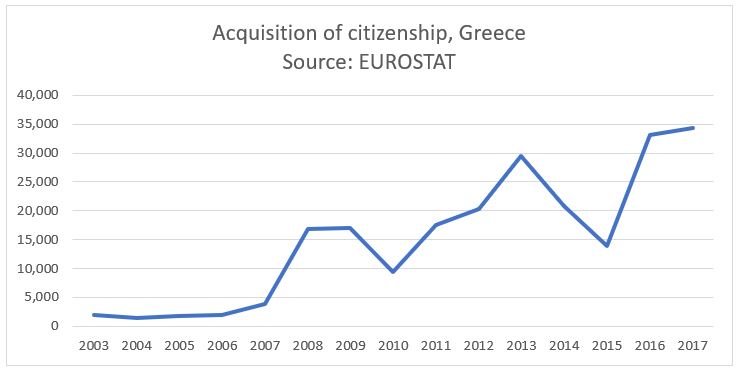

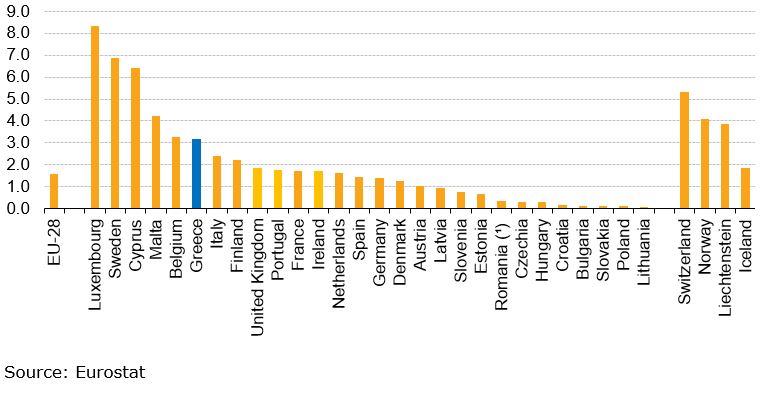

Greece has been slow to offer reliable paths to citizenship for foreign nationals. As a result, the number of citizenships granted has been low until relatively recently, in both absolute and relative terms. In 2003, when continuous reporting began, Greece ranked near the bottom among European member-states for the number of citizenships acquired by foreign nationals, granting only 1,896 citizenships, less than 0.2 per 1,000 inhabitants.

A major increase came in 2008-2009, with most of the beneficiaries being Albanian nationals. The numbers increased again, coinciding with the major immigration policy reforms in 2010 and 2015.

Today Greece is well above the EU-28 average for citizenships granted relative to the total population and ranks sixth among EU member-states with 3.2 citizenships granted for every 1,000 inhabitants in 2017.

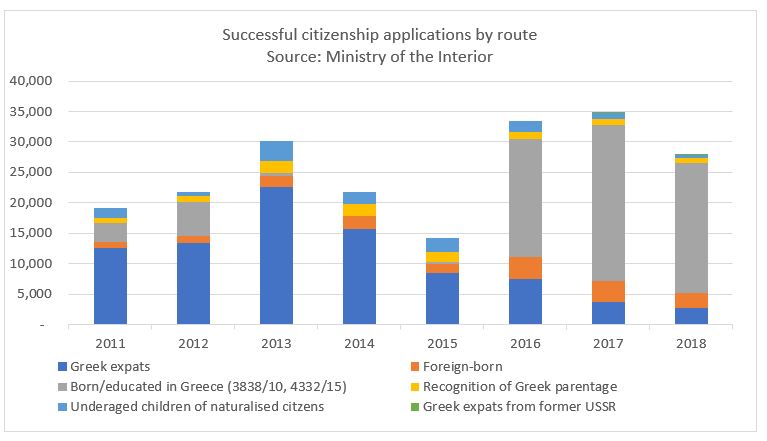

The Interior Ministry publishes more detailed statistics on citizenship acquisition, going back to 2011.

In total, 203,554 individuals acquired Greek citizenship over the past eight years through a variety of legal routes. Of these, 110,543 were awarded citizenship in the four years since the beginning of 2015, while only slightly fewer were successful over the prior four years, totalling 93,011.

There has been an overall increase of only 20 percent in citizenships granted since 2015 under SYRIZA compared to the preceding governments.

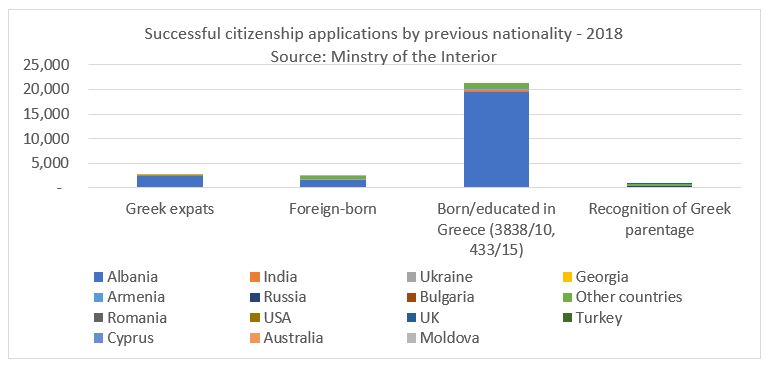

Over the entire period, the largest group of newly-minted citizens were Greek expats, almost 87,000 of whom who gained citizenship through naturalisation. The second largest group were second-generation immigrants, 75,669 of whom were granted citizenship. Just over 17,000 foreign nationals gained Greek citizenship through naturalisation.

The Ragoussis law (2828/10) resulted in an increase in successful applications between 2011 and 2013. Many of these applications were by members of the Greek diaspora, but there was also a significant number of second-generation immigrants granted citizenship in 2011 and 2012. Between 2013 and 2015, successful applications halved from 30,223 to 14,178.

The re-introduction of citizenship by birth and/or school attendance in Greece with law 4332/15 brought a sharp increase again in 2016, which continued in 2017 but started to tail off in 2018. In 2016, 58 percent of successful applications were by second-generation immigrants, while in 2017 and 2018 they represented close to 75 percent of the total.

The same period also witnessed a doubling in the annual numbers for naturalisations of foreign-born immigrants. Over the entire period 2011-2018, we can see that the number of successful applications by foreign-born residents doubled since 2015 compared to the previous period.

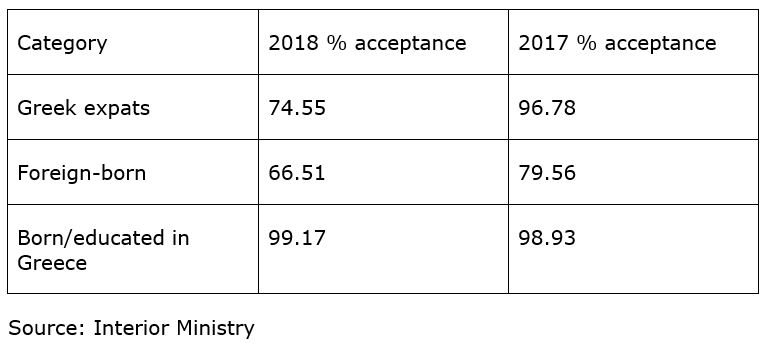

Foreign-born applicants, however, were much more likely to have their citizenship applications rejected, and the process seems to be becoming stricter over time. Only two in three foreign-born applicants were granted citizenship in 2018, down from four in five in 2017. Greek expats also face a reasonably high rejection rate. One in four applications from this group were rejected in 2018, up from less than 4 percent in the prior year.

The high rejection rate casts some doubt on the claims that citizenship boards have been applying their discretion in favour of foreign-born applicants.

In terms of country of origin, by far the largest group to successfully apply for Greek citizenship have been Albanian nationals. As recently as 2018, 9 in 10 naturalised Greek expats and second-generation immigrants granted citizenship were Albanian nationals, as were over 6 in 10 foreign nationals granted citizenship.

Could these numbers sway election results? The new citizens created since the last general election in 2015 correspond to just 1 percent of the electorate (making the outside assumption that they are all of voting age) (at the last count, 9,913,609 citizens were on the electoral rolls, and only 5,567930 voted). In marginal districts such as Athens A’, however, they could have a more decisive effect - but that is only assuming that they vote in large numbers and that they vote uniformly, neither of which assumption has been tested.

Finally, it is worth putting into context what one means when one speaks of an “express” citizenship process. Foreign-born citizens applying for Greek citizenship have historically had to wait at least four years for their citizenship interview. The most recent progress statistics, published on March 7 of this year, show that the interviews conducted in January and February 2019 related to applications submitted in the first quarter of 2015 for Athens, while other citizenship directorates had even longer lead times. The Thessaloniki directorate is currently examining applications dating back to the first quarter of 2013. Applicants starting the process today in Athens are still being advised to expect a four-year wait.

It is therefore a near-impossibility that the latest changes to the Citizenship Code will create new voters in time for this year’s elections.

What does it mean?

While the opposition claims that the SYRIZA government has been boosting the number of citizenships awarded in order to build its base, the statistics show a relatively modest increase compared to prior governments, despite two rounds of immigration reforms.

In fact, citizenships being granted today are in many cases the result of a multi-year application process endured by many of the applicants. The SYRIZA government has done much to bring access to citizenship closer in line with European and international practice, and the increase in numbers observed in recent years seems most likely to be the result of pent-up demand following an extended period of very few citizenship awards.

Finally, both the statistics and the practicalities of the process make it unlikely that many Afghan or Pakistani nationals will be swelling the SYRIZA base in this year’s elections, as most new citizens are of Albanian or east European descent.

Although the substance of the allegations is relatively easy to disprove, the innuendo in which they are couched will be harder to dispel.

Events such as the one addressed by Migration Policy Minister Vitsas clearly illustrate a strategy on SYRIZA’s part for courting immigrant communities with promises of easier integration and greater respect for their rights. There is nothing inherently shocking or untoward about this in the context of an election campaign, except perhaps for the casualness with which promises of easy citizenship seem to be offered from the speaker’s podium.

It is interesting to compare the controversy surrounding the voting rights of newly-minted citizens today to the cut-throat campaigning for the vote of the Greek diaspora from the former USSR by the two main political parties in years gone by. Press reports from as recently as 2008 indicate that promises of fast-track citizenship procedures, offers of jobs, subsidised mortgages, language lessons, charter flights and social support facilities in their countries of birth for a minority of citizens were considered fair play in election campaigns. By comparison, the de minimis implementation of international standards and a few loose words at the stump in front of a minority group look like tame electioneering.

The analogy is not exact, and times have changed since then in many respects, not least the amount of largesse available to dispense to target voter groups. However, the contrast between the perceived legitimacy of the tactics employed to court ethnic Greek immigrants and those used to appeal to other minorities suggests that, despite being dressed up as concern for gerrymandering, the complaints of the opposition are intended to tap into a growing xenophobic sentiment in the Greek public.

The upcoming election will also be the first in which 17-year-olds get the vote, thanks to a change to the electoral law in 2016 which will add an estimated 106,760 new voters to the rolls. In electoral terms, this heralds a change of similar magnitude, which however has attracted much less comment.

Urban legends such as that of the Afghan greengrocer find fertile ground in public attitudes increasingly hostile to immigrants. A recent Pew Research Study survey showed that an overwhelming majority of Greeks consider immigrants to be a burden on the host country – 74 percent of respondents agreed with this statement, the highest among all the countries surveyed, where the median was 38 percent. The same study showed that the portion of Greeks who view immigrants’ contribution positively has fallen from 19 percent to 10 percent since 2014.

In this context, it is also interesting to observe that the immigrant groups that feature most prominently in the opposition’s complaints are not the Albanians and east Europeans who will first get to vote in the upcoming electoral contests, and who are by now assimilated to a great degree, but the non-European Muslims who are the favourite target of European far-right rhetoric.

This has opened New Democracy up to claims of running a dog-whistling campaign, while its leader Kyriakos Mitsotakis is accused of indulging the nativist tactics in his party while focusing on his own drive to make it easier for overseas Greeks to vote.

In the meantime, SYRIZA has appeared opportunistic in claiming credit for the recent improvements in access to citizenship.

Broader issues, such as the potential damage being done to Greek political life and the country’s values, as well as the alienation of entire communities in the face of the demographic threat Greece is facing, have been largely absent from the debate between the two leading parties.

Parties take another look at granting vote to Greek expats

Parties take another look at granting vote to Greek expats  Parliamentary report highlights demographics challenge and urges immediate action

Parliamentary report highlights demographics challenge and urges immediate action  Greeks among world's most discontent with democratic process, survey finds

Greeks among world's most discontent with democratic process, survey finds