-

Inequality rises marginally in 2023, with 1.9 mln Greeks at risk of poverty

Inequality rises marginally in 2023, with 1.9 mln Greeks at risk of poverty

-

Workers lost almost 9 pct of real income last year, research shows

Workers lost almost 9 pct of real income last year, research shows

-

Latest census data shows demographic challenge is here as population shrinks, ages

Latest census data shows demographic challenge is here as population shrinks, ages

-

Risk of poverty drops to 26.3 pct, reflecting post-Covid rebound

Risk of poverty drops to 26.3 pct, reflecting post-Covid rebound

-

Poverty rate rises in 2021; even after social transfers 1 in 4 children are at risk

Poverty rate rises in 2021; even after social transfers 1 in 4 children are at risk

-

From the National Energy and Climate Plan to COP26: What has Greek climate policy learned?

From the National Energy and Climate Plan to COP26: What has Greek climate policy learned?

Is Greece facing a new migration crisis?

On August 30, a flotilla of 13 inflatable boats carrying 547 migrants arrived on a beach on the north coast of the island of Lesvos. Photos showing rows of beached dinghies and lifejackets triggered memories of the height of the migrant crisis in 2015/2016, and sparked media headlines warning of new dangers.

The noticeable surge in arrivals over recent weeks has brought the subject of migration back to the top of the political agenda and has put the spotlight on the New Democracy government right at the start of its term.

Political battleground

The government reacted to the increase in arrivals by announcing a series of emergency measures. They include accelerating the transfer of vulnerable migrants and refugees from the east Aegean islands to the mainland, and the reunification of unaccompanied children with their families in other European countries. On the other hand, the government announced that it would support the coast guard with new technology, strengthen border checks and introduce stricter asylum procedures, including abolishing the right to appeal first-degree asylum decisions, and intensifying police checks to identify and deport failed asylum-seekers.

As the largest party in opposition, SYRIZA has been critical of New Democracy’s handling of migration, accusing the new government of being slow to relocate migrants and refugees from the east Aegean islands to mainland Greece, of grandstanding over border protection and of violating international law and human rights by denying the right to appeal asylum rejections.

The government has responded by accusing their predecessors of preaching humanitarianism while allowing living conditions for asylum-seekers to deteriorate and leaving the borders open to human traffickers. The Ministry of Citizens’ Protection has issued a detailed response in which it criticises SYRIZA for leaving asylum programmes understaffed and underfunded, of failing to absorb European funds and of disregarding the needs of local communities. It also blames SYRIZA for allowing migrants to get stuck in overburdened reception centres on the islands, and for failing to provide organised accommodation on the mainland.

Underlying the political blame game is the sense that a new migration crisis may be brewing, and that Greece is ill-equipped to deal with it despite the funds and experience accumulated since 2015.

Numbers

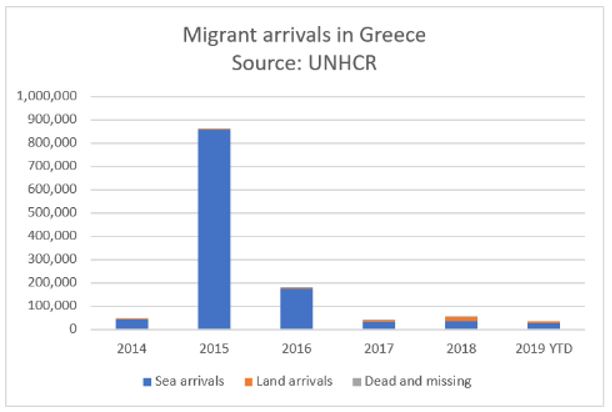

In absolute numbers, the recent arrivals are lower by an order of magnitude compared to 2015, when several thousand people were landing on the beaches daily. A total of 9,656 people arrived in Greece this August, compared to 5,806 in July. Exactly four years before, on August 29 2015, 5,558 migrants arrived on the Greek islands in a single day, and almost twice that many landed daily at the peak of the crisis that autumn.

However, August 2019 was the biggest month for arrivals since the signing of the EU-Turkey Statement of March 2016.

The increase has been accompanied by threats from Turkey that it will “open the gates” to Europe for migrants if it does not receive EU and US support to establish a so-called “safe zone” for rehoming Syrian refugees in northern Syria.

This year up until the start of September, 33,999 migrants have arrived in Greece, 26,078 by sea and 7,921 by land at the Evros border.

At the end of July, an estimated 84,000 recorded asylum-seekers, refugees and migrants remained in Greece out of the total 1,152,653 migrants who arrived in the country since the beginning of 2015.

Large numbers of people remain on the islands, where the situation has worsened again after the recent surge in arrivals. At the beginning of June 2019, official accommodation on the eastern Aegean islands – mostly in reception and identification centres - housed just over 16,000 people in facilities with a capacity of just under 9,000. More people reside in makeshift camps outside the official facilities. At the end of July the official number on the islands had increased to 19,900 as arrivals outpaced relocations to mainland Greece by about 3:1.

Decongestion of the islands has been mainly accomplished in spasmodic relocation operations, usually undertaken in winter due to the repeated failure to properly winterise the reception centres. As a result, around 7,000 refugees and asylum-seekers are currently accommodated in hotels in the mainland, under arrangements that had been intended to be temporary but that keep being extended.

Since 2015, around 59,400 people have been housed in EU-funded apartments on the mainland administered by the UNHCR, and a further 15,000 are housed in reception centres managed by the Greek military. These are less troubled by congestion, however many of the locations are remote, facilities can be insufficient, and the UNHCR notes that waiting times for asylum processing are longer on the mainland, with applicants routinely waiting two years or more.

Several thousand asylum-seekers are housed in makeshift accommodation outside of any official care or oversight. An example of this are the numerous squats operating in Athens, which provided another flashpoint in the recent debate when a number of them were very publicly raided and evacuated by police.

The situation is particularly acute for unaccompanied minors. There are over 4,000 children aged under 18 on their own in Greece, of which only one in four is housed in appropriate facilities and about 500 are homeless. Dozens of underage migrants are held in police detention, for lack of proper facilities, despite a ruling by the European Court of Human Rights against the practice.

Of the migrants remaining in Greece, just under 42,500 have been granted refugee or subsidiary protection since 2013, according to the Greek asylum service. This corresponds to an approval rate just over 45.3 percent of asylum applications submitted.

An EU scheme to relocate some 160,000 refugees and asylum-seekers from Greece and Italy to other European states expired with only 33,000 beneficiaries at the end of 2017. One notable exception has been a bilateral agreement to relocate 1,000 refugees from Greece to Portugal, which is currently in progress.

Under the terms of the EU-Turkey statement and the bilateral protocol adopted in March 2019, just under 2,500 people have been deported from Greece to Turkey since 2016. The rate of deportations has been declining since 2016, with Turkey periodically suspending migrant readmissions as a way of putting pressure on Greece – most notably in June 2018 as a response to the Greek courts’ decision to release eight military personnel who had fled after the July 2016 coup attempt – and most recently again in July 2019.

“A policy-made crisis”

There is clear evidence that the problems experienced now have been building up since the acute migration episode of 2015/2016.

Congestion in the island reception centres has been a concern for some time, prompting regular complaints and walk-outs by NGOs helping to run local operations. A recent report by RSA, a human rights non-profit organisation, characterised the situation on the islands as “mostly a policy-made humanitarian crisis”.

The report details how four years after the most acute phase of the migration crisis, Greece’s reception structures remain in perpetual “emergency mode”, with the absence of strategic long-term planning leading to an escalation of costs as well as a lack of effectiveness and quality in response to changing needs. Bureaucratic hurdles have often prevented the funds available from the EU and other international bodies from being absorbed, and adequate key staff, including medical personnel, from being hired. Refugee housing has also been hampered by the failure to put in place suitable long-term accommodation solutions.

The authors predicted that because of the lack of a strategic approach the system would not be able to cope with any significant increase in refugee arrivals.

In light of this, there seems little wiggle room for SYRIZA to escape criticism for the current state of affairs given that the response to the 2015/2016 crisis was developed almost entirely under its administration. Indeed, one of the most eloquent condemnations has come from a former spokesman for the SYRIZA government, Gavriil Sakellaridis, who now heads the Greek chapter of Amnesty International. While expressing alarm over New Democracy’s policies, Sakellaridis said in a recent interview that “the wretched living conditions in the reception centres on the islands, the allegations of pushbacks in [the border region of] Evros, the uncertainty over the continuation of the ESTIA [refugee housing] project are just a few of SYRIZA’s legacies”.

Policy shift

However, much of the political dispute is based on fundamental disagreements on migration policy between government and opposition, that have been playing out over recent years. Beyond the adoption of emergency measures in response to the surge in arrivals, the incoming New Democracy government has decisively reframed migration policy in line with its focus on a “law and order” agenda. One of its first acts was to reassign the migration policy portfolio to the Ministry for Citizen Protection, effectively defining it as a public order issue, rather than a citizenship or humanitarian issue.

Prior to the announcement of its emergency measures, the new government had already pledged to resume the deportation of failed asylum seekers to Turkey under the terms of the EU-Turkey agreement, and said that it would be reviewing 75,000 asylum applications including 9,000 that were at the appeal stage. At the same time, it took a series of actions seemingly designed to make life harder for migrants, such as withdrawing guidance on the issuance of social security numbers to new asylum-seekers (a pre-requisite for access to healthcare), and carrying out a number of highly publicised raids on squats housing migrants.

Policing the borders has also received more attention and funds under New Democracy, with a 50-million-euro budget earmarked for surveillance and communication technology to be shared between the coastguard and the military.

The new government’s tendency to treat migration largely as a security issue chimes well with the EU-level policy approach, where the drift towards an increasingly militarised response has been a strong trend at both European and national levels.

The budget for Frontex, the European Coast Guard and Border Guard Agency is on track for an exponential increase, from 6 million euros in 2005 to 1.3 billion euros for 2019-2020, and a proposed 11.3 billion across the period 2021-2027. A recently-noted switch from sea patrols to the use of aerial surveillance of the Mediterranean crossing routes has been condemned by critics as a way of securing borders “without the responsibility of saving lives” under maritime law.

It is in this context that the first crewless blimp was deployed in the island of Samos at the end of July to monitor movements from the Turkish coast.

On the other hand, the government has also pledged to ease the congestion of reception centres on the islands by rehousing asylum-seekers in permanent accommodation on the mainland and encouraging integration. A key theme of its first bilateral meetings with EU partners has been to renew the pressure for more refugee relocations among member-states.

It remains to be seen how the balance of policies will play out in practice. It appears for the moment that the external threat of a new migration crisis has played into the hands of a government elected in no small measure on the promise to take a tougher stance on migration. This seems to be balanced with a more pragmatic approach to managing the practicalities of the existing situation within Greece and easing some of the bottlenecks in the system though more competent administration.

The tension between these two aspects of New Democracy’s emerging migration policy exemplifies the tension within the governing party itself, between the promises of administrative reform and the frequently strident nationalistic rhetoric. The tack taken on migration could prove catalytic for the political direction of the party, and the broader political landscape in Greece.

The practical outcomes will depend in large part on the government’s capacity to make meaningful changes to the structures put in place to manage migration, for example to the way budgets are handled and staff are hired, and the interaction with local government and NGOs. These are challenging areas where the Greek state has historically been weak and inflexible. Results cannot be expected overnight, but may be possible to produce over a longer time frame with strategic vision and sustained effort. On the other hand, it is not certain that some of the more draconian measures will be practicable. In the case of the curtailment of asylum appeals, it has been questioned whether the measure would have any effect due to the limited capacity of the administrative courts, while it may also be open to challenge based on EU and international legal principles.

And, of course, not all of the outcomes depend on domestic factors. A key variable in how this will play out lies outside Greece, in the delicate geopolitics of the wider region.

Turkish threats

Turkey’s President Erdogan has threatened on several occasions to open the flow of migrants to Europe in an attempt to strengthen the country’s bargaining position on several issues, ranging from EU accession and emergency funding to the war in Syria. It is hard to ascertain how credible these threats are. When the EU-Turkey agreement was signed in March 2016, the number of arrivals in Greece had already declined sharply from their peak in autumn 2015.

Turkey currently houses 3.6 million registered refugees from Syria. It has recently started taking a harsher line within its borders, with harassment and mass round-ups of refugees, and the adoption of targets for deportations of migrants. In a recent statement, the country’s interior ,inister claimed that 56,000 migrants have already been deported to their countries of origin this year, with a target of 80,000. The latest threat was made in an attempt to force agreement to the creation of a “safe zone” administered by Turkey in norther Syria, which is mostly interpreted as a buffer zone against Kurdish forces.

There is little direct evidence of a policy to force migrants towards Greece, though it is possible that the Turkish coastguard could be receiving political encouragement to adopt a laxer stance towards people-trafficking. Large-scale incidents such as that of August 30 flotilla may be suggestive of such as strategy.

For now, the Greek government has been repeating its call for Turkey to come to the negotiating table with the EU, where it feels it has backing for a strong border policy within the European policy and legal framework. There has been no talk so far of a unilateral response of the type attempted by Salvini in Italy. Greece's position within the EU may be further strengthened if the government’s candidate Margaritis Schinas succeeds in being appointed Vice-President of the European Commission, while retaining the migration portfolio.

However, this is very much a double-edged sword as it comes with increased pressure from the European partners to deliver results in the form of managed migration flows.

EU-Greece island containment policy slammed as refugees endure squalid winter camps

EU-Greece island containment policy slammed as refugees endure squalid winter camps  New increase in flow of refugees to Greece causes unease

New increase in flow of refugees to Greece causes unease