-

Greek entrepreneurship by numbers: Micro-scale and macro impact

Greek entrepreneurship by numbers: Micro-scale and macro impact

-

Concerns about insipid public consultation process highlighted by treatment of climate plan

Concerns about insipid public consultation process highlighted by treatment of climate plan

-

Great Expectations: Is Greece 2.0 hitting the target?

Great Expectations: Is Greece 2.0 hitting the target?

-

Record year for Greek tourism raises concerns about sustainability

Record year for Greek tourism raises concerns about sustainability

-

What is driving the Greek housing market's recovery?

What is driving the Greek housing market's recovery?

-

Record FDI flow into Greece raises bar, but is it sustainable?

Record FDI flow into Greece raises bar, but is it sustainable?

Is the cost of Greece's public sector soaring again?

As Greece approaches the end of its bailout programme, claims are emerging that the SYRIZA-ANEL government has been on a public sector hiring spree at the expense of already over-burdened taxpayers, while seeking to entrench itself in the state through political appointments.

In the first part of this feature we looked at trends in public sector staffing over the last eight years. We found that some of the assertions made by the government’s critics about ballooning public sector numbers are exaggerated or misleading. At the same time, hiring patterns in some areas suggest that the rules are being bent in time-honoured ways, with worrying implications.

Some further claims aired about the government’s management of the public sector deserve consideration. Critics accuse the government of encouraging an unchecked proliferation of public bodies to house the party faithful, of allowing the cost of public sector salaries to go through the roof, and of appointing party friends and relatives to key civil service posts to sabotage the work of the next government. We look at the evidence for these claims in this second part of our feature.

Public bodies

In addition to claiming that the coalition has been swelling the ranks of the civil service to win votes, the opposition has also accused SYRIZA of presiding over a mushrooming of public bodies, designed to create positions for party loyalists. Some of these claims have already been disproven. Last year the opposition cited an apparent 65 percent increase in the number of government and wider public sector bodies between 2015 and 2017 as evidence that the government was creating superfluous structures on the fringes of the state to ensconce its supporters. Using the same data source for previous years, the government responded by claiming credit for eliminating 740 public bodies within a year of coming to power.

Neither claim is correct, as the Minister for Administrative Reconstruction Olga Gerovassili later conceded. The numbers, derived from the Labour Ministry’s Ergani database, record not the total number of public sector bodies but those bodies employing staff under private (i.e. fixed-term) contracts. As such, they are more a reflection of the use of private contracts in the public sector than the number of government agencies.

The Register of Services and Agencies of the Greek Public Administration is a tool established under the MoUs with the express aim of keeping track of public sector entities. Although the information in the register is not presented in an easily quantifiable format (and one may speculate as to the reason for this), we can see through a rough count that there are about 240 fewer public bodies in the 2017 edition compared to 2013. The count includes ministries, agencies of central and local government, as well as public/private entities directly supervised by ministries.

Despite anecdotal instances suggesting a proliferation of government and quasi-government entities, the evidence does not support such claims. Having said that, the wider public administration is far from streamlined. As our examination of “Chapter A” entities in the previous instalment revealed, it is still all too easy to establish or bring under the umbrella of the state a whole variety of structures with potentially overlapping remits, and very limited transparency or accountability. While the truth is far from the regime of anarchic growth evoked by the critics, this is clearly a space to watch.

Cost

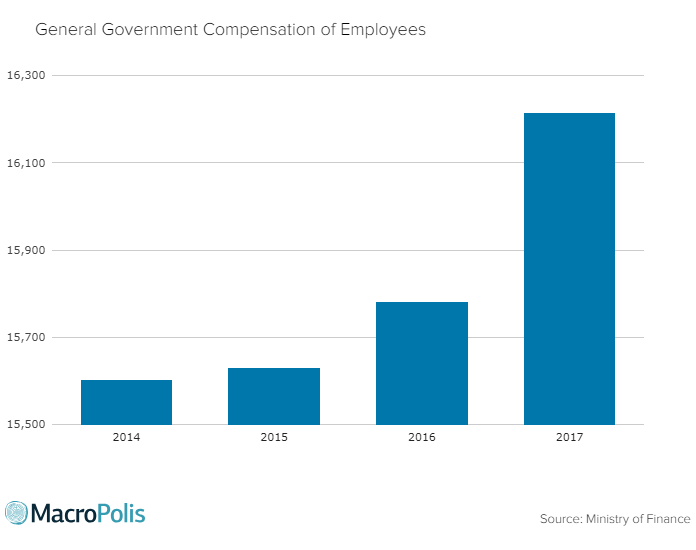

The fiscal impact of any expansion of the public sector is important, particularly at a time when the government is heavily focussed on raising revenues and cutting spending on services to meet fiscal targets. The claim is often repeated that the employment costs of the public sector have risen by 600 million euros since the SYRIZA/ANEL government took office. This claim is supported by the General Government Monthly Data bulletins released by the Finance Ministry, which show that the costs have gone up every year since the end of 2014, by a total of 612 million euros, or 3.9 percent.

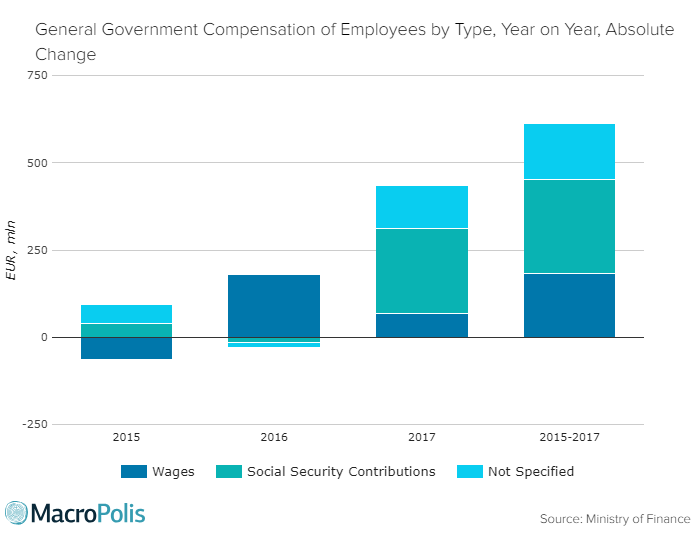

The cost escalation is often mentioned in the same breath as the increased number of public sector personnel or the size of public sector salaries. However, this linkage bears little scrutiny when we look at a breakdown of costs.

Almost half of the increase in public sector employment costs is due to an increase in the employer’s (i.e. the state’s) social security contributions, which went up by 268 million euros over the past three years on a net basis. The largest increase in social security contributions was recorded in 2017, which coincides with the implementation of a major overhaul of the social security system, which involved consolidating the majority Greece’s fragmented social security funds into a single entity, known as EFKA. The reform also harmonised the contributions system and introduced increases in both employers’ and employees’ contributions.

A further 161 million increase, counted under a residual category, “compensation not specified”, represents a mix of wages and social contributions from wider public sector structures which do not provide disaggregated reporting, including many “Chapter A” entities and local authority bodies. Given that this increase also coincides with the transition to EFKA in 2017 it is reasonable to assume that it also mostly reflects the move to the new contributions system.

Growth in public sector wages and salaries alone was a much more modest 1.4 percent, or 184 million euros, over a three-year period. But there is a cautionary note: public sector employment costs as a whole are expected to rise again in the current year to reflect a further increase in employer contributions, according to the 2018 budget.

Key appointments

A slightly different argument has been put forward regarding the appointment of senior civil servants, with New Democracy leader Kyriakos Mitsotakis accusing SYRIZA of planning a “capture of the state”. Mitsotakis claims that the appointment of dozens of senior civil servants a few months before the end of the government’s term is done with the intent to “mine” the path of the next government by placing SYRIZA loyalists in key posts. If elected, he has pledged to abolish half the posts, rewrite the appointment rules and bolster the civil service hierarchy.

Around the same time he made his pledge, a group of New Democracy deputies submitted a parliamentary question to the Administrative Reconstruction Minister which essentially accuses the government of gaming the selection criteria to favour current politically-appointed incumbents.

Is there any merit to these accusations?

First of all, there is little mystery as to the timing or the number of the new appointments, as they happen to be listed in the ESM report on the Third Review, which lays out the final milestones for the completion of Greece’s requirements under the MoU. The report is also supportive of the new selection process, which takes into consideration private sector experience and includes a structured interview in a departure from previous practice.

Under the rubric of “modernising the public administration”, the programme requires the government to launch calls for just under 70 Administrative and Sector Secretaries, 29 “Horizontal” Directors General, and more than 60 Sectoral Directors General. The appointees will be engaged under new terms of service, which include term limits that are explicitly decoupled from the electoral cycle. Ministers will not be able to remove them on a discretionary basis. The timeframe for appointments has been explicitly laid out in agreement to be completed by the expiration of the current programme in August 2018.

It is also worth putting these appointments into a broader context. It is generally accepted that the Greek civil service lacks independent authority, and there have been repeated attempts to reform and de-politicise it going back several decades. These have ultimately failed because of lack of political will, as successive governments have seen the benefit of making their own appointments, both to repay political favours and to ensure a compliant civil service. In the context of the bailout programme, establishing a more effective public administration was seen as a priority by Greece’s creditors, and was enshrined early on in the terms of the MoU. However, the changes ushered in by the programme in the name of reform have not always had the intended effect. The experience at the managerial levels of public administration has been particularly instructive.

In 2011, in an attempt to reduce headcount without resorting to unconstitutional redundancies, age and length of service criteria were used to usher public servants aged over 53 into compulsory retirement or “reserve” (in effect pre-retirement) status. Directors General, who were (and still remain) political appointees, were explicitly exempted; but around 10,000 civil servants, among them an entire cohort of experienced Directors, left the service as a result. Since then, the posts that were not abolished have been filled by direct ministerial appointment through provisional “emergency” procedures enshrined in the relevant legislation (law 4024/11). This effectively enabled the direct exercise of political discretion even further down the seniority scale than previously. In addition, delays in implementing the new administrative structures (organigrams) and the new selection procedures for the higher civil service grades have left the field wide open to naked political intervention with unprecedented reach.

Against this background, it seems particularly disingenuous to see politicisation in the introduction of appointment procedures which, even if flawed, have at least the potential to stem the galloping influence of politics on public administration. Moreover, the opposition’s populist promises to tear up the rulebook lack credibility given the fate of similar pledges by opposition parties across the political spectrum in recent years.

The charges of nepotism and cronyism are somewhat harder to dispel. The SYRIZA-ANEL government has raised eyebrows on several occasions by appointing party members or relatives with thin qualifications to key positions, and has not been particularly persuasive - or indeed concerned with - justifying such decisions on non-political grounds.

The recent case of the newly formed Hellenic Space Agency offers a perfect illustration of how the system can be (and has been, historically) gamed to favour the politically well-connected. A government agency created to allocate EU research grants was, according to the accusations of its recently departed chairman, subjugated to a politically-appointed Director General and pressured to allocate funds on a non-merit basis. Such personalised examples are the ones most likely to stick in the minds of the general public and therefore cause the most political damage.

Conclusion

Our brief survey has shown that parts of the Greek public sector are growing again following the radical cuts that preceded the SYRIZA-ANEL government. While some of the claims of rampant hiring and cronyism are out of proportion with reality and others are blatantly false, not all developments in this area are benign or innocent of political manipulation. The government may not be building a party state, but it does appear to be encouraging growth in areas of the public sector shielded from accountability, in ways that are not necessarily in the public interest. In doing so, it is showing that it is equally adept at playing the age-old political games of the pre-crisis establishment that it claims to be fighting.

With Greece’s exit from the bailout programme now in sight, it is a worrying sign that government and opposition are taking up positions to engage in a familiar ritual dance, claiming to promote public sector reform while tacitly colluding to undermine it. The end of the programme does not mean the end of the crisis and getting the country back on its feet is a challenge in which the public sector will be called on to do much more than implement policies under external duress. Entering this critical new phase with a weakened and compromised public administration could be one of the worst outcomes of the Greek adventure, and one which spells more trouble ahead.

Thessaloniki bus firm row adds to public sector challenges

Thessaloniki bus firm row adds to public sector challenges  Coalition's moves on public sector hirings under scrutiny

Coalition's moves on public sector hirings under scrutiny  Are hirings in the public sector out of control?

Are hirings in the public sector out of control?