-

Great Expectations: Is Greece 2.0 hitting the target?

Great Expectations: Is Greece 2.0 hitting the target?

-

Record year for Greek tourism raises concerns about sustainability

Record year for Greek tourism raises concerns about sustainability

-

What is driving the Greek housing market's recovery?

What is driving the Greek housing market's recovery?

-

Record FDI flow into Greece raises bar, but is it sustainable?

Record FDI flow into Greece raises bar, but is it sustainable?

-

Balance of payments shows shipping on course for bumper year, but economic benefits unclear

Balance of payments shows shipping on course for bumper year, but economic benefits unclear

-

One unicorn does not a Silicon Valley make: positive news on startup front also highlights limitations

One unicorn does not a Silicon Valley make: positive news on startup front also highlights limitations

Are hirings in the public sector out of control?

In recent weeks the Greek government has come under sustained criticism from the main opposition party, New Democracy, for its management of the public sector.

“The situation in public administration is out of all control,” charged New Democracy leader Kyriakos Mitsotakis in a recent statement. “The government is proceeding with thousands of irregular appointments and grantings of tenure, while creating superfluous public bodies in order to ensconce party relatives and friends.”

The opposition backs up its accusations with figures which claim to show that the government has hired 21,000 permanent public sector staff and 15,000 contractors, at a cost of 600 million euros.

These accusations have touched a raw nerve at a time when fresh pension cuts and tax hikes continue to come into effect, and unemployment remains stubbornly lodged above 20 percent. The accusation that the government is feathering its own nest in such difficult times for the general population could not fail to excite a reaction. In addition, charges of cronyism strike at the heart of the SYRIZA/ANEL coalition government’s claims to be a fresh, untainted political force, fighting corruption and doing away with the rotten political establishment and its long-held practices.

The opposition goes on to accuse the coalition of using its last months in office to “seize the keys to the state” by appointing its own people to key positions, allowing it to control the apparatus of government even after it has lost power.

The accusations are clearly not intended just for domestic consumption, but are meant to catch the ear of Greece’s creditors, an ear finely tuned to detect any wavering from reform targets at a critical juncture when the country is approaching the end of its bailout programme. The question of whether Greece can be trusted to manage its own affairs once the heavy surveillance of the programme is lifted is more than topical, as discussions start to focus on shaping the country’s post-MoU regime.

In the first of a two-part feature we look at recent developments in the Greek public sector to examine how closely the picture painted by the government’s critics matches reality.

Has the public sector been growing?

Based on the statistics drawn from the register of public employees, we can start by making two broad observations.

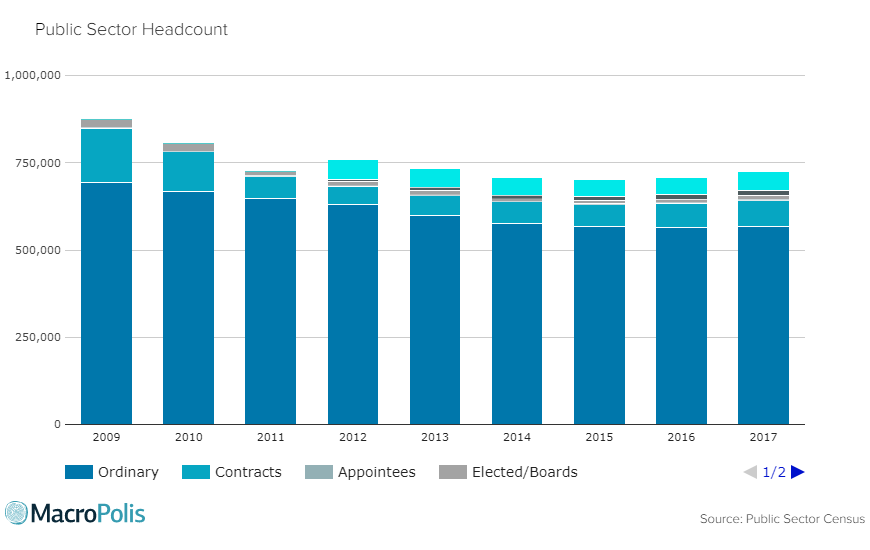

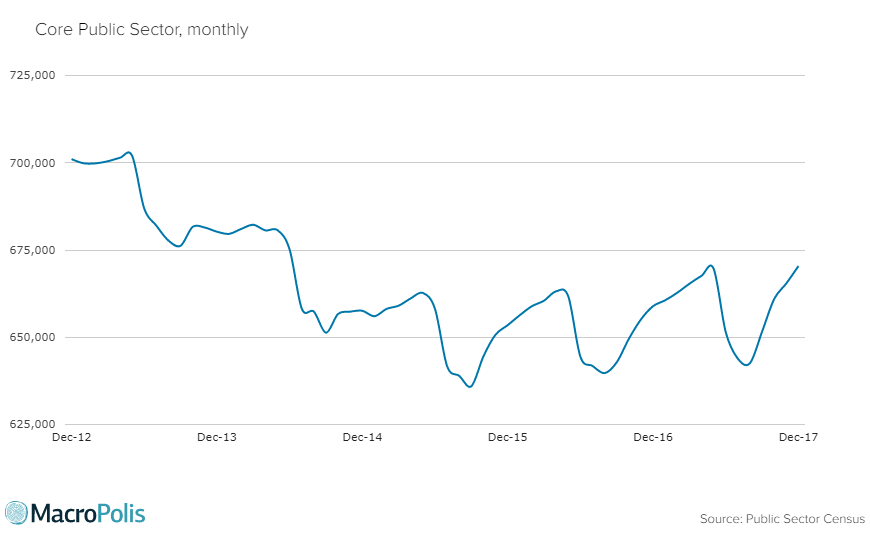

Firstly, the size of the Greek public sector has been slashed since the beginning of the crisis, perhaps more than most people realise. The core public sector ended 2017 smaller by about 200,000 jobs compared to the end of 2009. This represents a net reduction of about 23 percent across central government, decentralised administrations, local government and independent authorities. The reductions exceed the overall target of 150,000 agreed under the terms of the first MoU by a considerable margin.

Secondly, following the initial dramatic cuts, the rate of reduction slowed down. The trend is now reversed. With the exception of permanent civil servants (“ordinary staff”), every category of the core and wider public sector has grown in the last three years under the present government.

The question is, how much of this new growth represents the necessary replenishment of an over-pruned public sector, and how much might be down to a politically-motivated hiring spree as charged by the opposition? Or, to put it in less adversarial terms, what is driving the increases, and are they likely to improve the quality of public services?

To answer this question, we need to look in a bit more detail at the different groupings within the wider public sector.

Ordinary staff

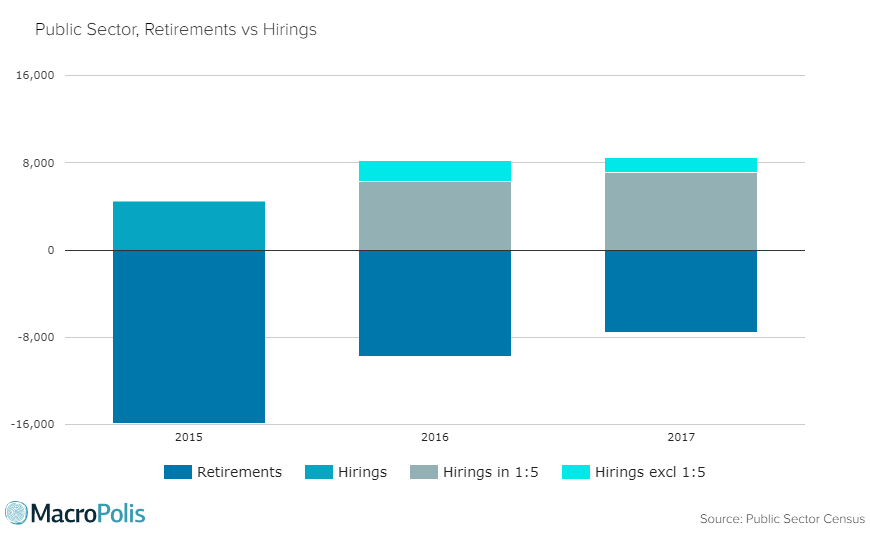

The hiring of permanent staff by ministries, independent agencies, decentralised and local government and the public bodies supervised by them is subject to a strict 1:4 (previously 1:5) attrition rule laid out in the MoU, meaning one new hire is permitted for every 4 (previously 5) departures.

The tight controls exercised on this category of public employees probably account for the fact that the headcount has been falling on a net basis every year between 2010 and 2016. Overall, their numbers fell by 126,046 between 2010 and 2017, despite a relatively modest increase by just over a thousand in the past year. When the opposition quotes the number of 21,000 new permanent civil servants it appears to refer to gross hirings, which have mostly been counterbalanced by departures.

While on the face of it the balance of hirings and departures does not adhere to the attrition rule, the annual window of measurement may obscure lags between the two sets of figures. For instance, while the number of permissible hires for 2017 under the 1:4 rule was 2,453, the government claimed an additional allowance of 4,644 hires remaining from 2016, bringing the total cap to 7,097. The actual number of hires by the end of the year was 7,063, which would put it marginally below the cap using this adjusted calculation.

More recent hiring plans have been more controversial. In February the government announced the creation of 8,166 permanent positions in sanitation and maintenance for local authorities, to replace temporary positions which are presently covered by contract staff. Announcing the new hiring plans, Interior Minister Panos Skourletis argued that the hirings would not violate the 1:4 attrition rule, thanks to legislation brought in in 2016 which loosened hiring caps for self-funding functions (for example functions funded by municipal taxes).

His conviction was not even shared within government, including by Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras who conceded that the case would have to be argued with the institutions.

Contract staff

The curbing of contract jobs was seen as a “quick win” the reform programme, as entire functions could be abolished from the government payroll overnight simply by not proceeding with renewals. Over 100,000 contract positions were abolished between 2010 and 2012 in the initial phase of “rationalisation”. However, since 2013 their numbers have been creeping up steadily. The total number was up to 75,810 at the end of 2017 from a low of 54,150 at the end of 2012, a net increase of 21,660 or 40 percent (in fact the numbers are often higher mid-year as contracts follow a seasonal pattern peaking in late spring). The net increase during the two terms of the current government is 15,118, or 25 percent, on a year-end basis.

The absence of caps has clearly allowed more hires to be made through this route, and the increase in numbers may conceal deeper structural issues.

Hiring criteria for fixed-term contract positions have historically been looser than those applied to the staffing of permanent roles. Up until 2009, applicants for fixed-term contracts were exempt from the civil service entry exams, and successive governments encouraged the practice of using rolling fixed-term contracts as a route to permanent employment, as a universally acknowledged form of political patronage. This practice reached its apogee with the infamous Pavlopoulos law of 2004, which converted over 36,000 fixed term contracts into permanent positions over the four years of the last pre-crisis New Democracy government.

The use of temporary contracts as both a substitute for and as a backdoor route to permanent appointments is therefore a well-trodden path, and the municipal sanitation sector is notorious in this respect. This does not necessarily mean that contract staff are surplus to requirements, rather it is more likely that that they fulfil real needs that are not being met by permanent staff, who were the actual recipients of political favours.

Under the terms of the MoU, short-term or hourly contracts remain easier to create, as they are exempt from the attrition rule. This is because, despite appearing in the government census, the salaries of contract workers are often not paid for by general taxation, but are covered by various self-funding mechanisms such as local government taxes, EU programme funds or own revenues.

As in the past, the recent growth in the fixed-term contract sector appears on the face of it to address the ongoing needs of local authorities in core functions which were disproportionately affected by the horizontal cuts of the programme. However, the prospect of converting these positions into tenured appointments has stirred controversy, because it appears to come with a lifting of safeguards that were intended to protect against the clientelistic practices of the past.

A recent legislative amendment abolished the 24-month limit on fixed-term contracts and the mandatory 3-month interval between contracts. Advertised requirements for new permanent contracts appeared to restrict applicants to those with previous contract experience, eliciting a strong response within the Supreme Council for Civil Personnel Selection (ASEP) which had to approve them, and from the opposition. This has opened the government up to the accusation that they intend to reinstate the conveyor belt between fixed-term contracts and permanent state jobs.

While the numbers involved are not comparable to those of the past, there does appear to be a distortion in public sector hiring, where the contract sector is being inflated as a possible prelude to growing the numbers of permanent staff in an artificially limited number of sectors.

In effect, the trends suggest that the government is hiring where it can (sanitation workers), rather than where the needs might be more pressing (for example medical and nursing staff). This would represent a continuation of past practices rather than a break from them, entrenching historical distortions in the public sector. Regardless of their fiscal impact or the quality of the appointees, such practices would undeniably compromise the overall quality of public services in the long term.

Political appointees

Political appointees are a favourite target for scrutiny by the opposition, despite numbering just a few hundreds and therefore being a vanishingly small portion of the public sector. It is true that the numbers have increased by about 30 percent under the coalition government, to a total of 2,487 by the end of 2017. However, they were already creeping up in previous years. The only governments not to have boosted the number of political advisors since the start of the crisis are interim (non-elected) governments.

It is also questionable how important this figure is in the bigger scheme of things. While it would not be desirable to allow the number to inflate indefinitely, the key characteristic of political advisors is that their tenure ends with that of the government that appointed them. Therefore, while it might provide a way to secure “jobs for the boys” in the short term, the impact of appointees on long-term policy making, and therefore the ability of any government to “capture” the public sector by this route, is limited.

Private Law Entities

The final category with a noticeable increase in staff numbers is Private Law Entities (so-called “Chapter A” entities, known in Greek by the acronym NPID). This heading covers a heterogeneous collection of bodies that form part of the wider public sector. Some started as private foundations and were absorbed into the public sector at various points in time, while others are government agencies in the more modern administrative sense, which proliferated from the 1990s onwards. They include among their number research and cultural institutions, local environmental agencies, bodies coordinating drug rehabilitation programmes and libraries.

Lack of transparency, and the whiff of mismanagement and cronyism enveloping a number of them, made them an obvious target in the rationalisation drive, and legislation was brought in to limit their numbers. Law 4109 of 2013 closed eight public bodies and merged 157 legal entities, while law 4250 in the following year abolished 23 services and agencies. The resulting downward trend in staff numbers associated with them can be observed over the period 2013-2015.

However, the trend has now reversed, and the headcount associated with these bodies grew by 1,273 (3 percent) in 2016 and 4,923 (10 percent) in 2017. The Register of Services and Agencies of the Greek Public Administration shows that the count of private law entities included in the central administration increased from 76 in 2013 to 82 in 2017. This represents further, if marginal, evidence of wider public sector expansion in areas under lighter scrutiny.

It is not clear what needs this expansion serves and whether it represents the most efficient way to serve the public interest. In some cases, we may simply be witnessing the effects of crisis decision-making, including the absorption into the public sector of over a dozen cultural institutions threatened with bankruptcy. A forced move like this will clearly have a fiscal impact but also a more intangible emotional resonance, and its wisdom can only be judged over the longer term. It is not immediately clear how many other decisions in this sector conform to this pattern.

Special cases

Another census category that has grown over the years of the crisis is so-called “special cases”. Though technically not employees, this group is paid through the Single Payment Authority, and includes such disparate categories as scholarships, beneficiaries of reimbursement through court decisions, and private contractors. Their numbers have swelled from 3,413 in 2012 to 15,601 at the end of 2017. By far the largest increase occurred prior to 2015, when their ranks more than tripled over three years, and continued at a slower pace under the current government. It is hard to know what to attribute the increase to, however the fact that it coincides with big cuts in ordinary staff positions suggests either a reclassification or some kind of compensatory action.

A provisional conclusion

The evolution of public sector headcount in various categories suggests that some of the opposition claims of “out of control” hiring are overblown or misleading. The Greek public sector has shrunk dramatically over the last eight years, and any increase is taking place from a very low base. In some areas, we may be seeing, at least in part, piecemeal responses to crisis situations rather than a grand strategy to grow the public sector. However, there are some trends that suggest the perpetuation of weaknesses in the Greek public sector. Well-trodden paths to clientelistic hiring, such as local authority contracts, are being maintained and even further eased in the name of efficiency, with dubious implications for the quality of public services.

In Part 2 we will examine the evidence for the proliferation of public bodies, take a closer look at the cost of public services under the current government, and try to see if there is any merit in the accusations of “state capture” by looking at appointments to senior public service posts.

Public sector evaluation and hirings in the spotlight

Public sector evaluation and hirings in the spotlight  Thessaloniki bus firm row adds to public sector challenges

Thessaloniki bus firm row adds to public sector challenges  Coalition's moves on public sector hirings under scrutiny

Coalition's moves on public sector hirings under scrutiny