-

Great Expectations: Is Greece 2.0 hitting the target?

Great Expectations: Is Greece 2.0 hitting the target?

-

Record year for Greek tourism raises concerns about sustainability

Record year for Greek tourism raises concerns about sustainability

-

What is driving the Greek housing market's recovery?

What is driving the Greek housing market's recovery?

-

Record FDI flow into Greece raises bar, but is it sustainable?

Record FDI flow into Greece raises bar, but is it sustainable?

-

Balance of payments shows shipping on course for bumper year, but economic benefits unclear

Balance of payments shows shipping on course for bumper year, but economic benefits unclear

-

One unicorn does not a Silicon Valley make: positive news on startup front also highlights limitations

One unicorn does not a Silicon Valley make: positive news on startup front also highlights limitations

Tracing the decline of the middle class as parties vie for its votes

The plight of the Greek middle class has emerged as the dominant theme of the campaign for the July 7 national elections. Since key constituencies, including private and public sector workers and the young, abandoned governing SYRIZA to hand New Democracy a comfortable 9.5 percent lead in the May 26 European Parliament elections, the parties have been vying for the middle-class vote.

New Democracy blames SYRIZA’s tax policies for “overburdening” hard-working middle-income earners in order to pay for handouts. The government, on the other hand, blames the austerity policies of its predecessors for plummeting incomes and living standards.

We look at some of the key facts and figures around the experience of the Greek middle class in the course of the financial crisis. The picture that emerges is quite sobering, yet with the focus almost entirely on who is to blame, the public debate fails to rise to the challenge.

Who is middle class?

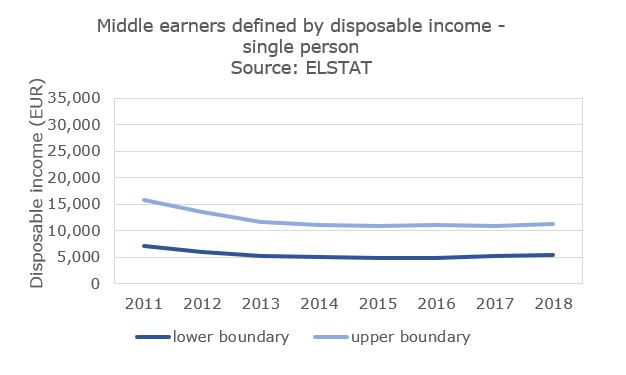

Most economic studies use a quantitative definition of “middle class”, which essentially equates it with “middle income”. The OECD definition includes those making between 75 percent and 200 percent of the national median disposable income – for Greece this translates into annual earnings after tax and social contributions between 7,894 and 21,050 US dollars for a one-person household in 2016. According to the OECD, around 57 percent of Greeks are captured by this definition of “middle income”, which coincides almost exactly with the portion of the population which identify themselves as “middle class”.

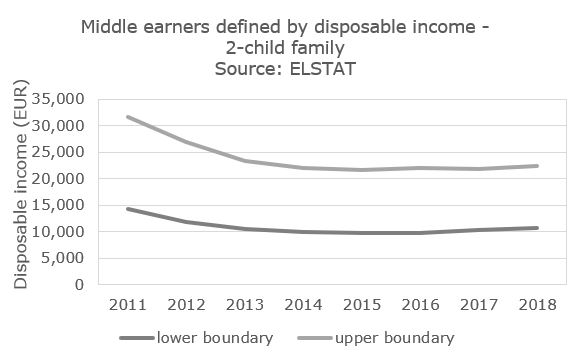

The Greek Statistical Authority (ELSTAT), using the EU-SILC data (EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions), divides the population into income quartiles based on disposable income. For 2018, the middle two quartiles, which may be thought of capturing middle incomes, include those taking home between 5,373 euros and 11,200 euros annually in the case of a one-person household, and between 10,746 and 22,400 for a couple with two children over the age of 14. (It is worth noting that both the OECD and the ELSTAT figures are extracted from national statistics and standardised for international comparison, therefore they cannot be compared directly to gross earnings or tax data).

A purely quantitative definition of the middle class means that its absolute boundaries will change through time. If incomes rise or fall as a whole, the definition of the “middle earners” changes accordingly.

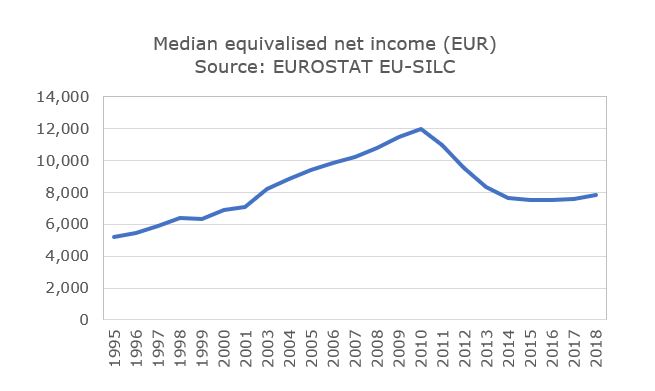

Adjusted for inflation, the average (median) households’ disposable income fell by more than a third between 2010-2016 and has shown only a small recovery in the last couple of years.

In 2009, middle incomes in the ELSTAT definition ranged between 8,000 and 16,625 euros. A notional person earning 16,000 euros would be considered a middle earner in 2009 but a high earner in 2018. Someone earning 7,000 euros in 2009 would be defined as a low earner, but in 2018 is considered a middle earner.

Falling incomes, rising taxes

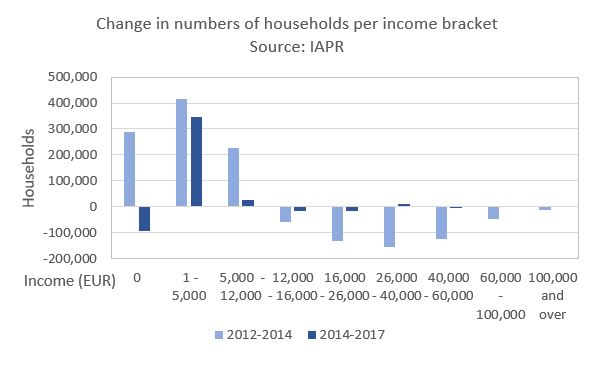

The information from tax returns shows that there has been a dramatic downward shift in earnings over the years of the crisis (comparable data is only available from the Independent Agency for Public Revenue (IAPR) from 2012 onwards).

The shift was most pronounced between 2012-2014, when the number of households declaring incomes below 12,000 euros swelled by almost a million, with the largest increase seen in the number of incomes under 5,000 euros. Some of these will have been new taxpayers entering the system (just under 400,000 households were added to the tax base over the same period). However, over half a million households fell out of the higher brackets, and it is fair to assume that a significant portion of them will have ended up lower down the scale due to lower incomes rather than exiting the tax system completely (e.g. through emigration).

In the subsequent period (2014-2017) we see a further net increase in the number of households declaring under 5,000 euros annual income. This is almost entirely due to new taxpayers (almost a quarter of a million new tax returns counted over the period), and potentially households who had previously filed zero tax returns now declaring small incomes.

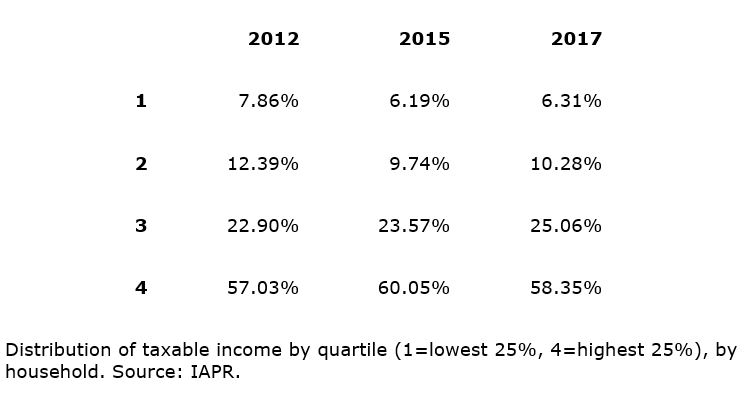

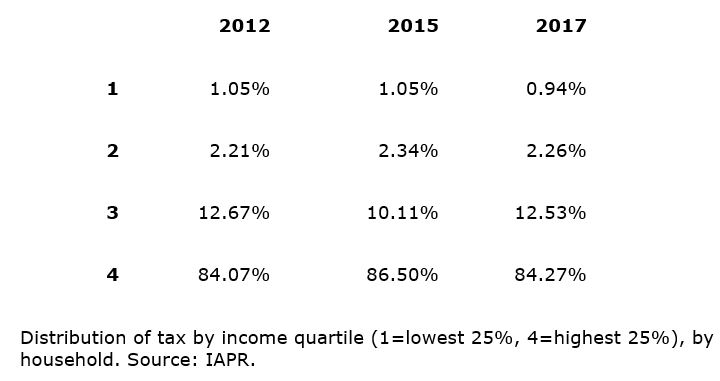

The share of income generated and tax contributed by middle income groups has remained fairly stable over the period for which we have data. IAPR figures show the middle 50 percent of taxpayers accounted for 33 to 35 percent of incomes declared throughout the period 2012-2017 (ELSTAT puts the figure at around 44-46 percent due the differences in methodology noted above). The tax paid by the “middle income” group made up 12-14 percent of the tax payable during the same period. In both cases, there is a slight decrease in the middle of the period, and this is primarily due to the larger share taken by higher income groups.

These findings challenge some of the assertions of critics who claim that the middle incomes’ share of the tax burden has increased disproportionately in recent years.

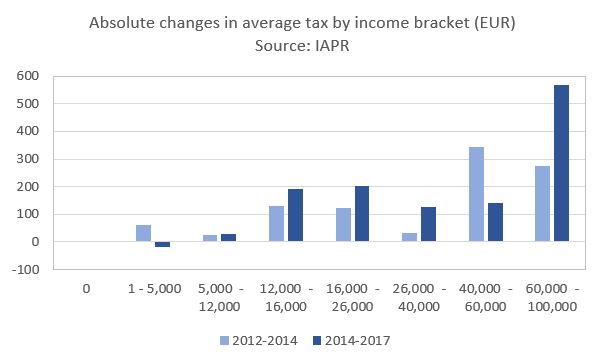

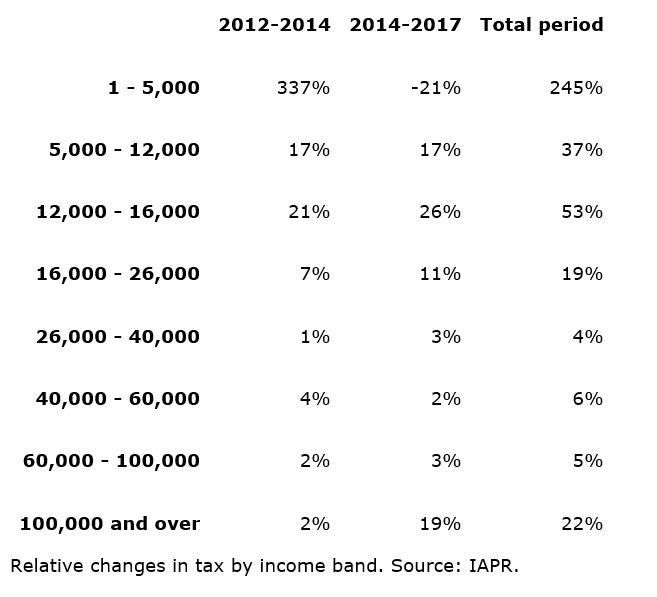

Almost all income groups have seen successive increases in their income tax since 2012, with the exception of the lowest earners who saw their tax increase threefold between 2012-2014 (though from a very low base), but benefited from a subsequent decrease post-2014 under the SYRIZA-led coalition. In most cases, the increases were steeper under SYRIZA than their predecessors. Households in the 5,000 to 12,000-euro range received two successive 17 percent tax increases over the two periods. Households earning 12,000-16,000 euros saw their tax increased by 21 percent in 2012-2014 and 26 percent in 2014-2017. Increases were generally less pronounced in relative terms the higher one goes up the scale, with the exception of a 19 percent hike for earners over 100,000 euros in the latter period.

However, as we noted in a previous analysis about half the tax burden is borne by the top 5 percent of earners, which has been the case throughout the past decade.

Identity

“Middle class” identity is about more than just income. People self-identify as middle class through a variety of cultural as well as economic factors, including occupation, education and asset ownership. Under the combined pressure of plummeting incomes and more aggressive taxation many of these traditional trappings of the middle class have not only come under threat, but have become a burden for many.

Greece has traditionally had one of the highest rates of home ownership in Europe. The introduction of property taxes as part of the economic adjustment programme increased the cost of ownership at the same time as many borrowers found it increasingly difficult to service their mortgages. In a recent survey, one in four borrowers were not able to meet their obligations to the banks. Over 40,000 foreclosed properties are due to be auctioned off by the banks in the coming years, in addition to the 20,000 already sold. Although foreclosures have so far only applied to second homes and business premises, the home-ownership rate has fallen from 81.6 percent to 73.9 percent in the space of 12 years, despite a 40 percent drop in house prices and a largely stagnant property market.

High educational attainment, once seen as a passport to success, failed to provide insurance against the recession – quite the opposite in fact. One of the findings of a recent analysis of income and social inclusion statistics by the think tank Dianeosis was that university graduates lost a higher proportion of their income than those with fewer qualifications (45.1 percent was lost by degree-holders, compared to 42.5 percent for high-school graduates, and 37.5 percent for those with primary school education or lower). Working-age, highly skilled university graduates formed the main thrust behind a wave of emigration from Greece in the years of the crisis. Nearly 430,000 Greek citizens emigrated between 2010 and 2017 according to EUROSTAT; of those who had left by 2013, it is estimated that 63 percent were university graduates.

Workers, and particularly self-employed professionals are faced with higher contributions as a result of much-needed social security reforms, while enforcement measures put in place to boost revenue collection are widely seen as intrusive and debilitating. Close to 1.2 million taxpayers who have fallen behind on their taxes by as little as 500 euros are subject to compulsory measures including automatic seizures from their bank accounts.

The Dianeosis study found that over the years of the crisis, families with children were more likely to find themselves in the bottom 20 percent of earners. Unemployment and self-employment are also more likely to land one in the lowest earning group than previously.

Comparisons

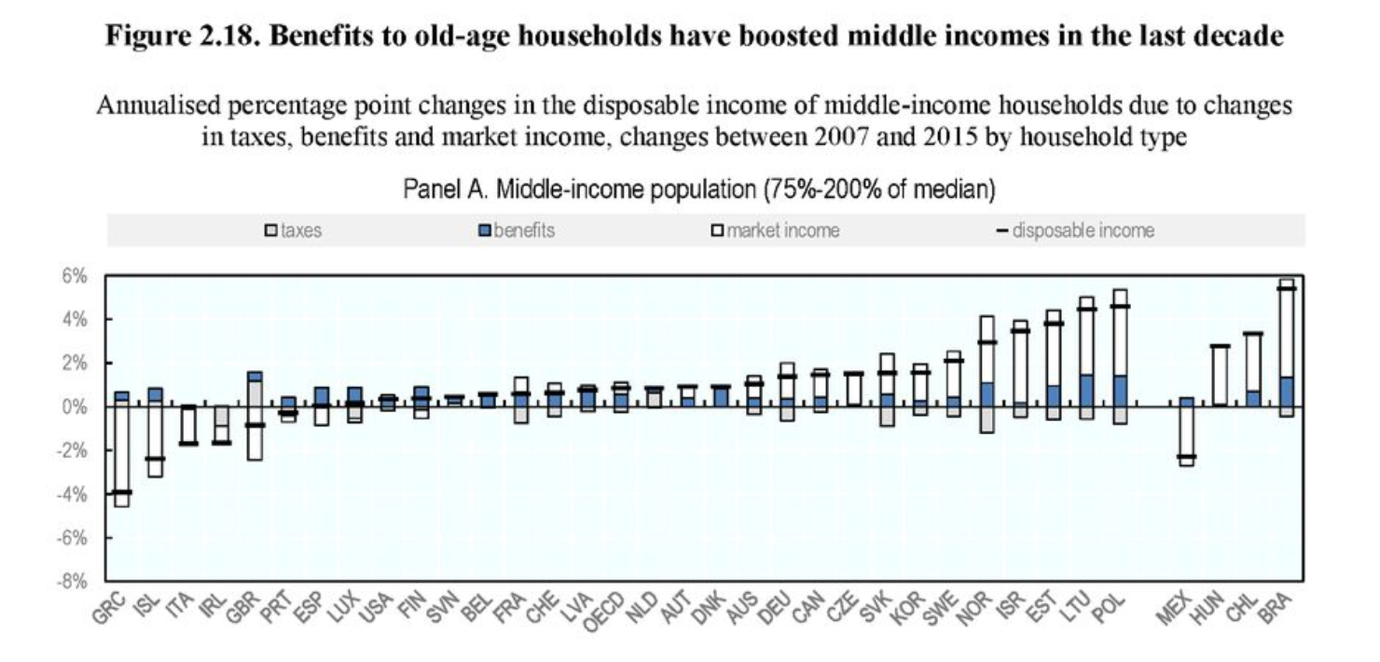

The “squeezed middle class” is a phenomenon observed across the developing world and one that is deployed with increasing regularity in political campaigns, however Greece is at the extreme end of the spectrum in many respects. An OECD study shows that the Greek middle class lost disposable income between 2007 and 2015 at the highest rate among the countries studied (4 percent annually compared to under 2 percent in Italy Ireland). And whereas in Ireland the loss is party attributed to higher taxes, in Greece and Italy it is due almost entirely to falling market incomes.

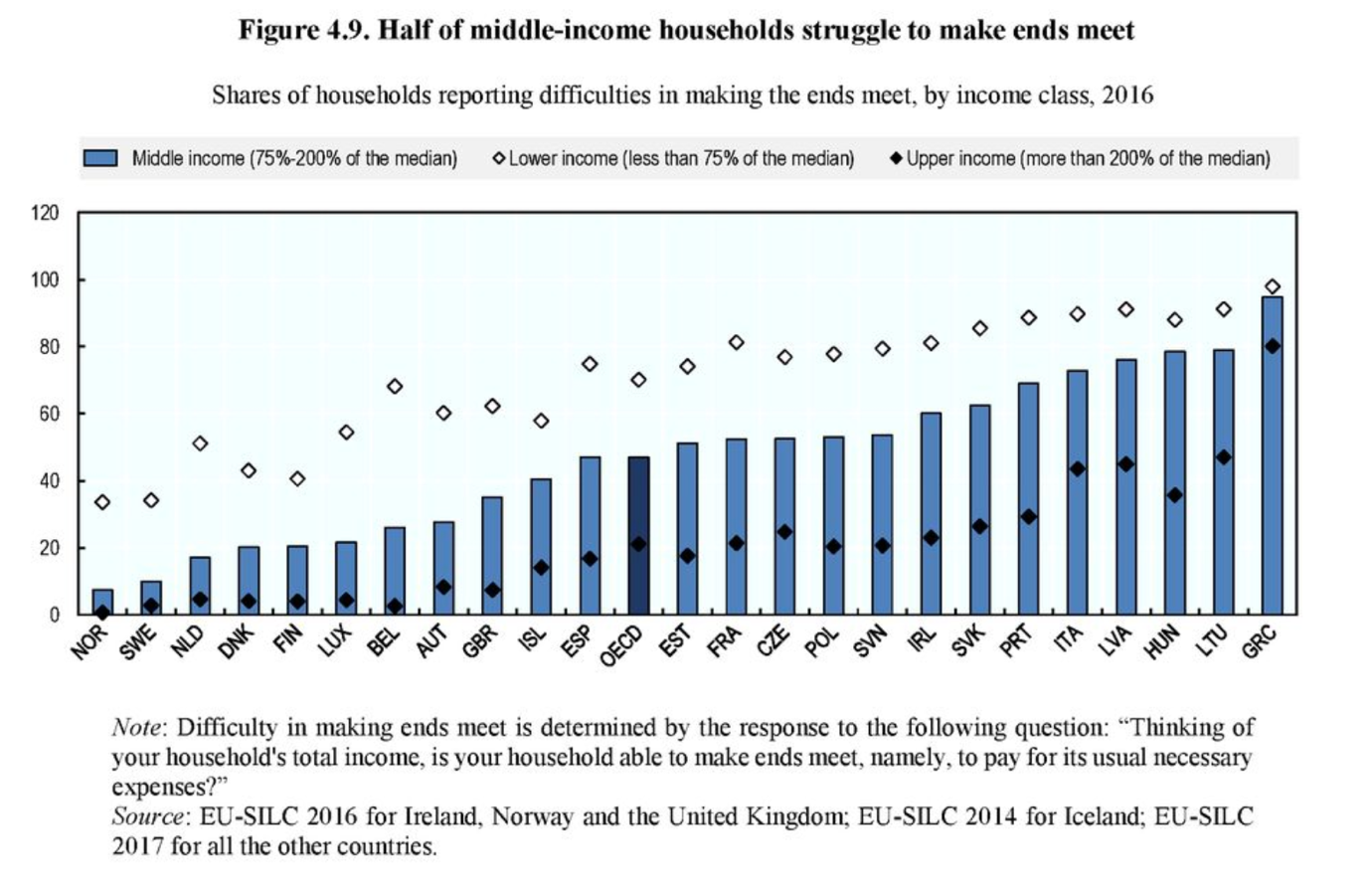

The vast majority of middle-income households in Greece struggle to pay their necessary expenses, compared to about half of households across the OECD.

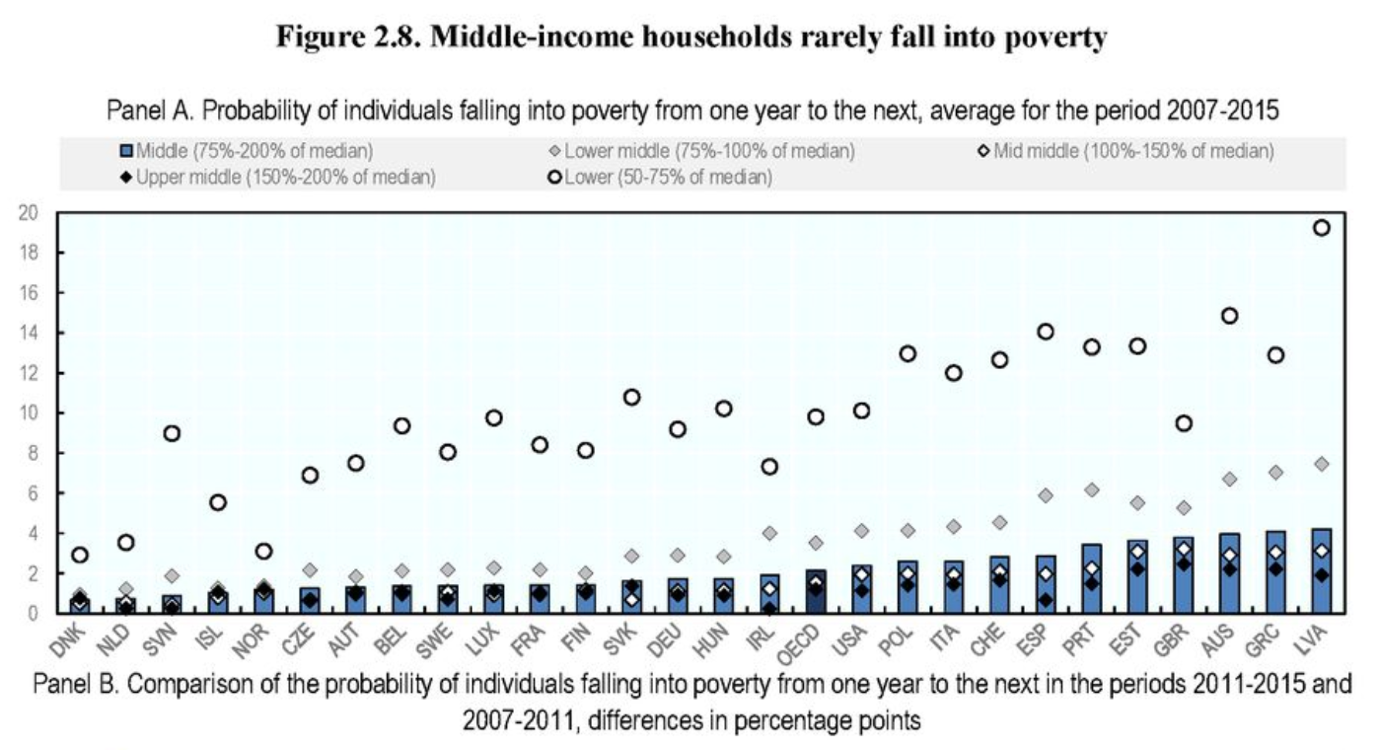

Middle-income households in Greece have had a higher risk (4 percent) of falling into poverty from one year to the next during the crisis than most countries in the study.

While the political debate in Greece may superficially resemble that in other parts of the developed and developing world, the reality is that a large section of the population who enjoyed the trappings of a middle-class lifestyle prior to the economic crisis now have to cope with a much more precarious existence. The collapse in living standards exceeds any recently experienced in the global context. The severity of the situation is unfortunately not matched by the level of the public discussion on the subject.

Politics

Inevitably, definitions of the middle class and descriptions of its plight have been muddled considerably by politics.

Defending the distribution of the so-called “social dividend” in 2017, SYRIZA’s Finance Minister Euclid Tsakalotos argued that the criteria extending up to families earning 18,000 euros “cover part of the middle class, because (those with) incomes between 12,000-18,000 are not in the lower classes”. Many then were shocked to hear the numbers, but they do in fact conform to ELSTAT’s middle 50 percent. However, pressed to define the “disappointed” middle classes during a TV interview following the party’s recent EU elections defeat, the same minister defined the middle class as two-child families earning between 25,000 and 40-45,000 euros. By any metric these would fall squarely within the country’s top earners in today’s terms, though they may have been middle-to-upper earners in 2009 terms. It is worth noting that a gross income of 33,000 euros today puts a household in the top 5 percent of earners.

This is either a severe case of cognitive dissonance, or a last-ditch appeal to the pre-crisis middle class rather than to today’s middle-earners as such. The opposition and its commentators are guilty of similar sleight-of-hand, by routinely lumping both middle and top earners into the “beleaguered middle class” – witness New Democracy’s Dora Bakoyianni, whose definition groups together earners of between 20,000 and 70-80,000 euros.

Any attempt to define the target group explicitly is like nailing jelly to wall, and that is why professional politicians mostly avoid it, preferring instead to allude to professional and cultural identity, and aspirational qualities. Conservative politicians in particular know that aspiring middle-class voters can be easily persuaded to vote for policies favouring wealthier groups. This is especially true if, as is the case in Greece, the voters in question were able to sustain a solid middle-class lifestyle within recent memory.

In this sense, another technocrat, Tsakalotos’s alternate minister Giorgos Houliarakis, gifted the opposition a winning card when he told Parliament’s budget committee in 2017 that burdening the middle classes, the self-employed, honest and diligent taxpayers, “was a conscious choice that the government has made in the transition, in order to help the weakest and most vulnerable”. While the evidence shows that middle earners’ fortunes declined much more precipitously in the earlier years of the crisis, well before SYRIZA came to power, such admissions of intent have played into the hands of the traditional parties of the middle class, and particularly New Democracy, who regularly accuse the government of unfairly targeting the middle class.

Conscious even then of perceptions, SYRIZA has been working to correct the narrative ever since, arguing that with the exit from the economic adjustment programme it has been preparing to repay middle earners for propping up the budget in past years. However, data-based arguments rehearsed to highlight recent improvements in disposable income have proved ineffectual. It is hard to celebrate an extra 146 euros a year in pocket for a two-child family, as Tsakalotos did in a recent tweet, while comparing it to the estimated 5,258 euros of annual income lost between 2011-2014. Even though the losses happened on someone else’s watch, the limited size of the subsequent gains only serves as a reminder of the yawning gap separating today’s earnings from pre-crisis levels. Meanwhile, SYRIZA’s failure in government to deliver on earlier flagship pledges such as abolishing the ENFIA property tax continues to provide ammunition for the opposition.

New Democracy, for its part, have focussed on the putative role of taxation in reducing middle class incomes. Leader Kyriakos Mitsotakis has promised to “end the mass over-taxation of the middle class”. Rhetoric aside, the party has been rather thin on the detail of its tax plans for middle incomes, while making very specific commitments regarding the upper and lower ends of the income scale. Instead it leans heavily pledges to cut taxes on activities traditionally identified with the middle class - eating out (lower VAT on restaurant bills), entrepreneurship (reduced corporate tax) and home ownership (across-the-board cuts to property tax) – while promising more high-quality, high-earning jobs and support for working families.

Are the pledges credible? With both parties already committed to costly measures – for example keeping a significant portion of the newly impoverished middle class below the tax-free threshold – it is questionable how many of their other pledges they will be able to put into practice without a significant acceleration in economic growth.

While the slide into lower earnings was steeper in the earlier years of the crisis, the failure to recover to any perceptible degree is creating a reservoir of frustration that has already swung one set of elections and looks likely to swing the next. However, it remains to be seen to what extent a change in political leadership will be enough to improve the lot of the Greek middle class.

It is clear from the comparative data that the situation in Greece goes well beyond the terms of the now-familiar “squeezed middle class” debate, and yet it is striking that no-one in the political sphere is proposing much beyond the well-trodden approaches for dealing with it. For example, both main parties have chosen to ignore warnings about the skewed safety-net policies that protect pensioners at the expense of the unemployed and working-age families. Rather they have voted to (or silently conceded to) shelve scheduled pension cuts and award pension bonuses while cancelling measures to boost childcare and employment. Improving access to public healthcare, modernising public education and improving further education and re-skilling, and other more radical policy solutions do not get much consideration in the public debate.

IAPR annual data shows growing tax pile and pressure on middle-income taxpayers

IAPR annual data shows growing tax pile and pressure on middle-income taxpayers  OECD report highlights stress on Greek middle class during crisis

OECD report highlights stress on Greek middle class during crisis  Parties' competing tax pledges come up against challenging reality

Parties' competing tax pledges come up against challenging reality