-

Another crisis chapter closes, triggering final round of debt relief measures

Another crisis chapter closes, triggering final round of debt relief measures

-

Exit from enhanced surveillance nears, but fiscal commitments bind Greece until 2060

Exit from enhanced surveillance nears, but fiscal commitments bind Greece until 2060

-

Enhanced surveillance concludes, but more reforms and tougher fiscal targets lie ahead

Enhanced surveillance concludes, but more reforms and tougher fiscal targets lie ahead

-

Some tasks, risks left as Greece takes another step to exit from post-bailout surveillance

Some tasks, risks left as Greece takes another step to exit from post-bailout surveillance

-

Latest EC review clears path towards end of enhanced surveillance process in 2022

Latest EC review clears path towards end of enhanced surveillance process in 2022

-

Creditors give thumbs up for 10th post-MoU review, underline pandemic legacy

Creditors give thumbs up for 10th post-MoU review, underline pandemic legacy

IMF insists fiscal targets unrealistic, cites historical evidence to support case

From the start of Greece’s third European Stability Mechanism, programme in the summer of 2015, the International Monetary Fund had been calling for realistic assumptions in the assessment of Greece’s debt sustainability.

One of those assumptions, which still separates the Fund and eurozone creditors and keeps the IMF on the sidelines, is the combination of the duration and the scale of the primary surpluses that Greece has to maintain.

In an interview with Naftemporiki newspaper on Wednesday, IMF mission chief for Greece Delia Velculescu explained the Fund’s position.

“We have said many times that Greece cannot sustain primary surpluses above 1.5 percent of GDP for a prolonged period,” she said. “This view is based on Greece’s own historical track record, and on the broader international experience, which shows that periods of sustained very large surpluses are rare, and depend on highly favorable initial economic conditions.

“We did recognize, however, that Greece could temporarily reach higher surpluses, through exceptional compression of spending or other one-off measures. This is what happened in 2016, when a reduction in spending beyond what was budgeted, together with temporary factors, such as tax offsets related to arrears clearance with ESM funds, helped to support a much-higher-than-targeted primary surplus.”

In the documentation accompanying the Precautionary Stand-by Agreement approval the IMF argues in detail its case based on historical evidence in Greece and cross-countries based on prior fiscal adjustments data.

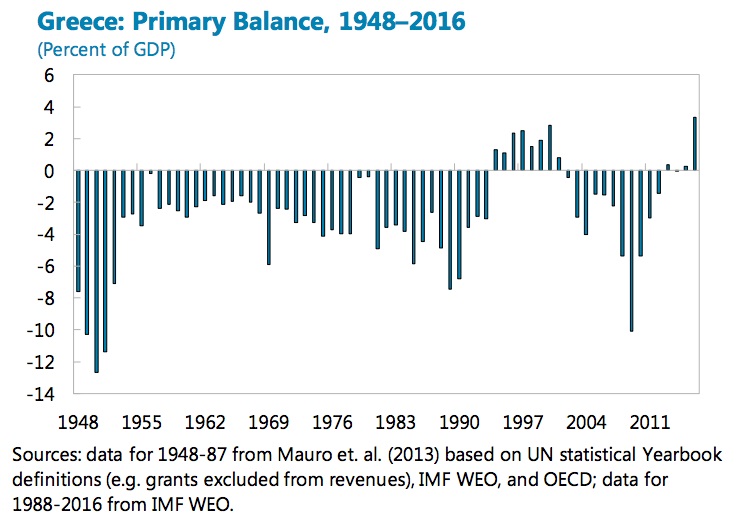

In the 70 years following the post-war period, Greece has been running a primary deficit in the region of 3 percent of GDP. The only exception was a period of eight years during 1994-2001 when it was running a primary surplus of 1 percent to meet the overall deficit target of 3 percent for euro adoption, though quickly reversed to primary deficit of 2 percent immediately following the euro ascension.

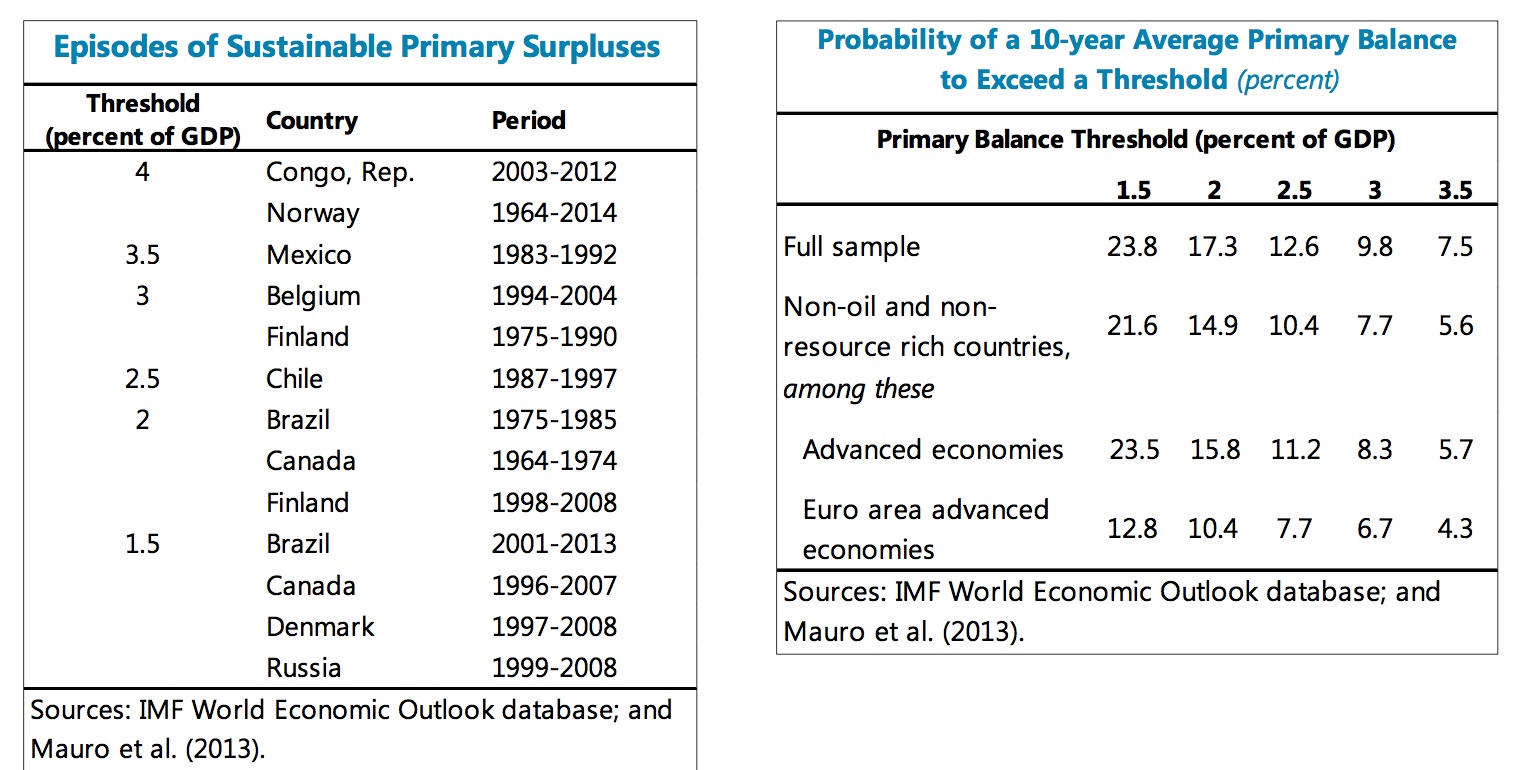

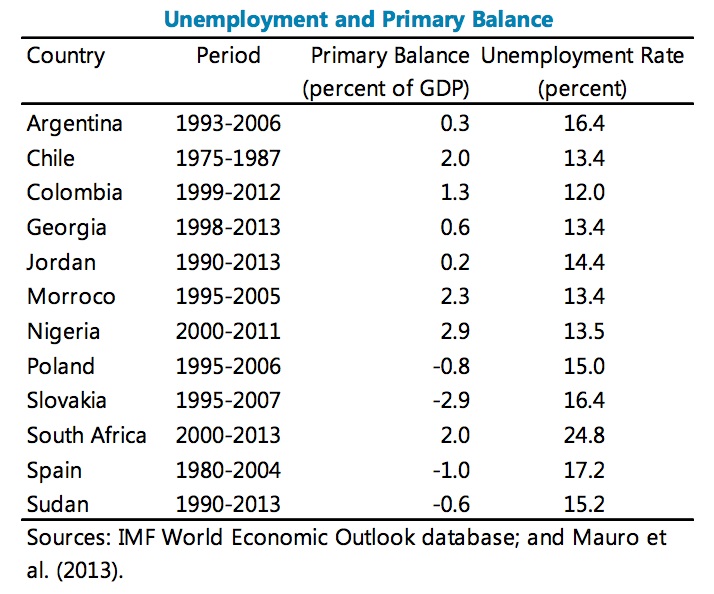

Cross-country evidence in the post-war history supports the Fund’s conservative stance since a sample covering 90 countries in the 1945-2015 period shows only in 13 cases a primary surplus in excess of 1.5 percent of GDP could be maintained for more than 10 consecutive years. When the primary surplus threshold is increased to 3.5 percent of GDP only 3 cases have managed to maintain that target and, when excluding resource-rich countries, only one country in the sample has managed to meet and maintain for longer than a decade.

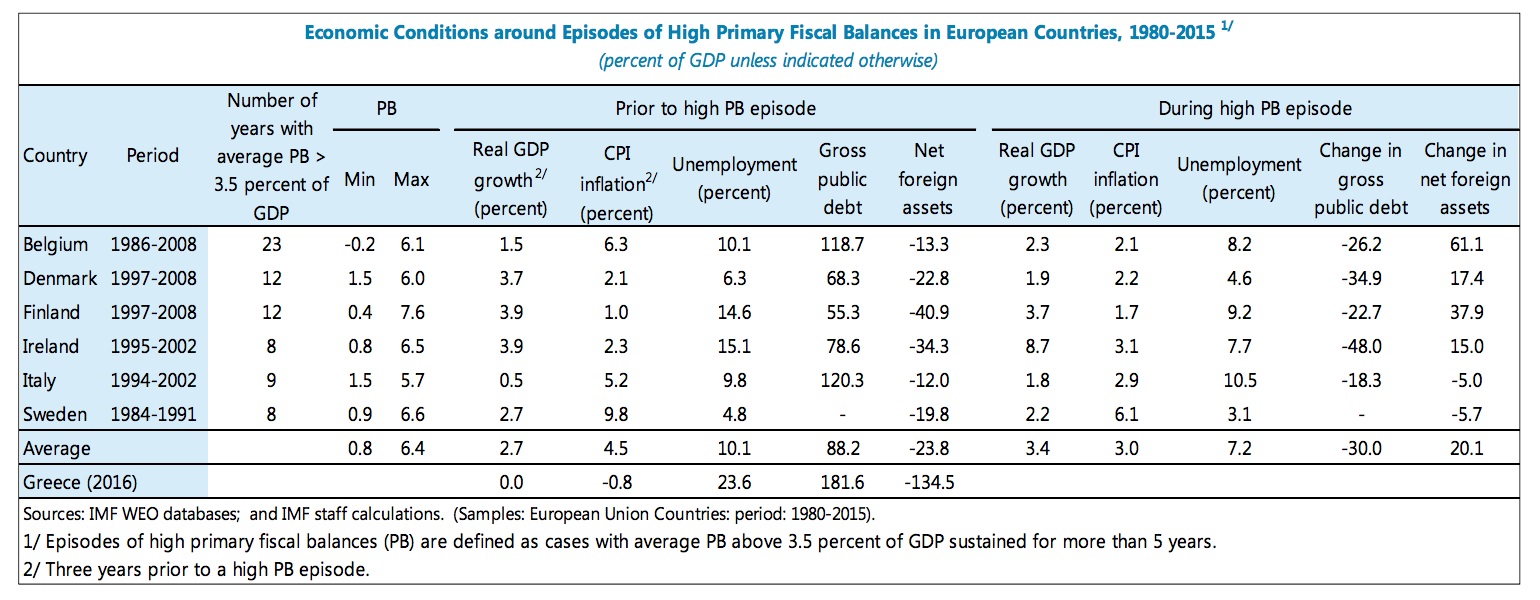

The IMF makes a specific point to highlight the significance of economic conditions in achieving and holding on to high surpluses. Among EU countries that managed to reach those goals, before entering the high surplus period they had strong real GDP growth (2.7 percent) and high inflation (4 percent). Unemployment was moderate (10 percent) and net foreign debt was low (24 percent of GDP). Greece is about to enter a period of high primary surpluses agreed with its eurozone creditors having experienced a substantial contraction in economic activity during the crisis, years of deflation, unemployment well above 20 percent and heavily indebted.

Additionally, during the high surplus periods, those EU countries experienced rapid growth, modest inflation and contained unemployment, which according to the Fund suggest that sustained periods of high primary surpluses require strong economic growth to take hold rather than large-scale fiscal consolidation effort.

There is an additional piece of historical evidence that supports the IMF’s view that sustainable primary surpluses are challenging. Large primary surpluses that are achieved through strong fiscal adjustment are often reversed following strong spending pressures that had accumulated during the consolidation period.

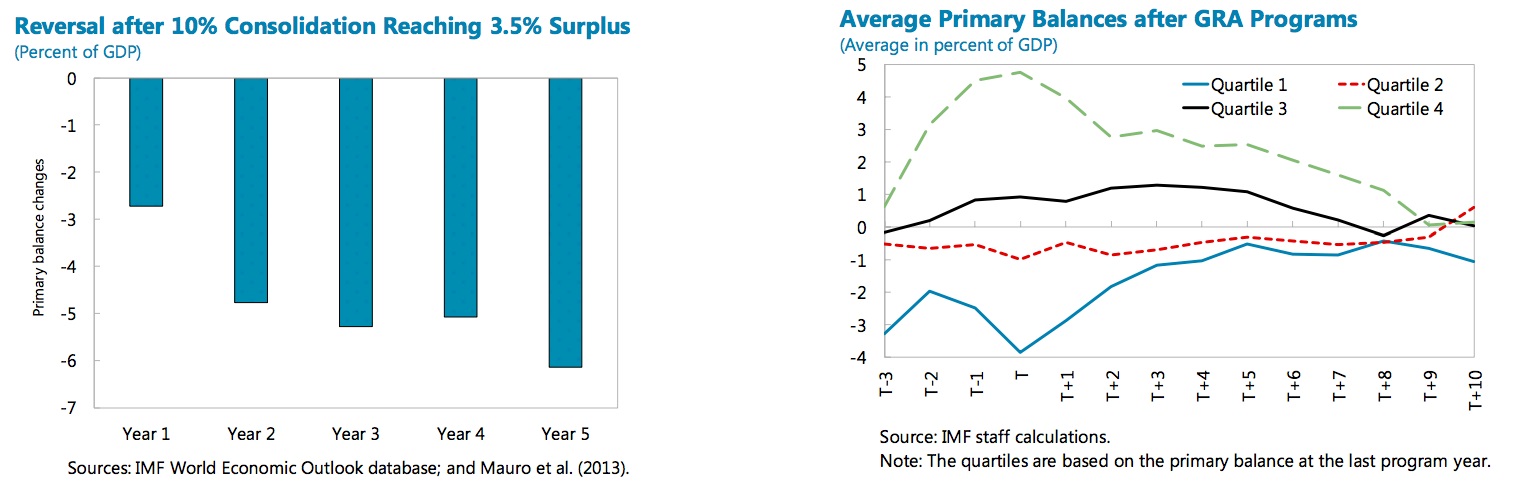

Looking at 55 episodes of previous fiscal consolidations of similar nature to Greece’s where the primary balance improved by more than 10 percentage points, the IMF concludes that only a fifth of those continued the improvement path as in the overwhelming majority of cases the primary balance deteriorated after such strong fiscal adjustment.

The historical experience doesn’t only capture the change in fiscal attitude but also the speed at which the reversal takes place. Once the adjustment ends, in all 55 cases the primary balance deteriorates by -3/4 percentage points of GDP each year. Out of those 55 cases, in those that the fiscal adjustment achieved a primary surplus of 3.5 percent of GDP, the primary balance deterioration in the five years following the adjustment is about 1.25 percentage points of GDP annually.

In the Fund’s own experience, based on countries that have undertaken adjustment under an IMF programme, after a strong improvement during the programme the primary surplus falls in half in a five-year period with most of the deterioration happening in the first two years.

Unemployment is a substantial drain on fiscal resources as it impacts both sides of the budget through the need for higher social spending and lower revenues due to the loss of personal taxable income. Greece is in a particularly problematic position as it finds itself amongst a small group of just 10 countries that have had an employment rate of more than 20 percent in the post-war era.

High unemployment is associated with low primary balances as double-digit unemployment for more than 10 years averages historically a primary deficit of 0.5 percent of GDP.

As the IMF foresees double-digit unemployment in Greece until the middle of the century, pressure for social spending is likely to remain a challenge.

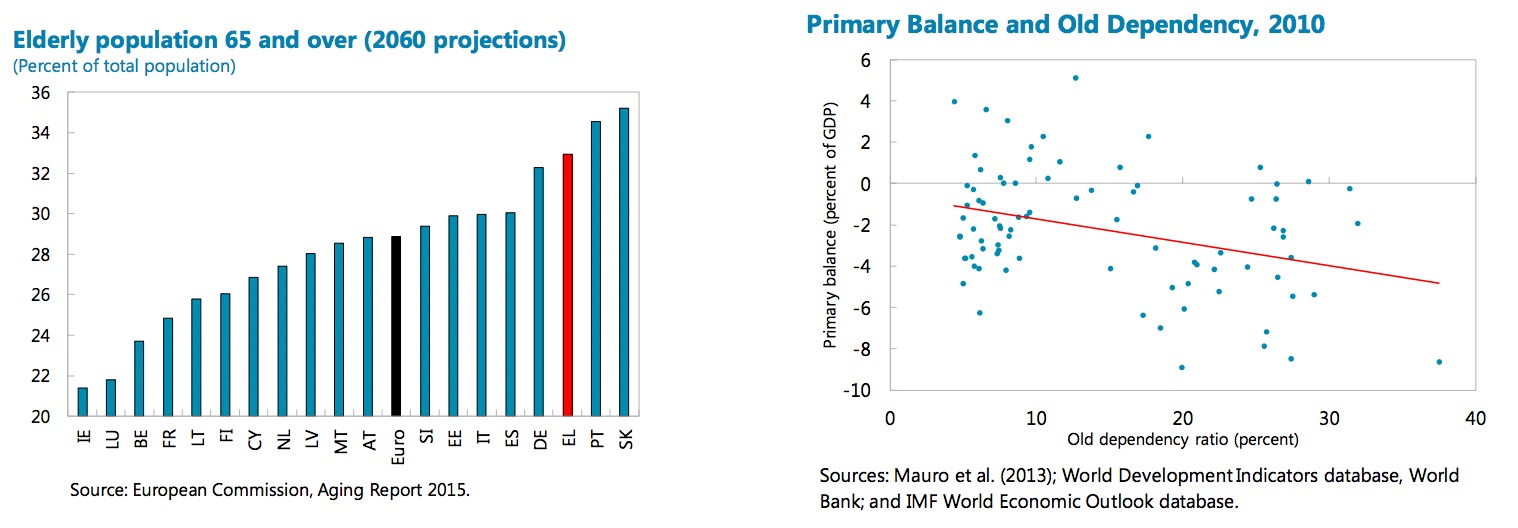

Greece’s unfavourable demographics also negatively affect the sustainability of high primary balances, as countries with shrinking working populations are not capable to deliver high surpluses for long periods as the tax paying portion of the population decreases while there is a corresponding increase in those that need support, healthcare and pensions.

Greece has a high old-dependency ratio and the European Commission’s Ageing report sees the portion of the population that will be 65 and over by 2060 to increase by 10 percentage points close to one in three. The Fund concludes that following Greece’s fiscal adjustment in the crisis, health spending has been severely suppressed to one of the lowest levels in the eurozone and given those levels are not sustainable such spending is expected to increase.

The IMF’s final piece of historical evidence to wrap up its call for realistic assumptions in terms of Greece’s fiscal trajectory relates to the absence of monetary and exchange rate tools. Countries without an independent monetary policy find it hard to maintain primary surpluses, as they don’t have the ability of aggregate demand management. Improvements of primary balance by more than 10 percentage points in a five-year period are associated with an environment of monetary easing and Greece lacks both.

In her statement following the approval in principle of the Stand-By Arrangement (SBA) last week, IMF managing director Christine Lagarde stressed that “this target should be reduced to a more sustainable level of 1.5 percent of GDP as soon as possible, to create fiscal space for better targeting social assistance, stimulating public investment, and lowering tax rates to support growth.”

IMF revises fiscal estimates upward, sees debt ratio at 162.8 pct in 2022

IMF revises fiscal estimates upward, sees debt ratio at 162.8 pct in 2022  IMF approves programme "in principle," repeats position on debt and reforms

IMF approves programme "in principle," repeats position on debt and reforms  IMF sets out why it stands apart from eurozone on long-term growth prospects

IMF sets out why it stands apart from eurozone on long-term growth prospects