-

EBRD reports highlights demographic headwinds Greece has to navigate

EBRD reports highlights demographic headwinds Greece has to navigate

-

OECD report highlights stark contrasts in health system

OECD report highlights stark contrasts in health system

-

Greece’s 14–29s: Ambitious, anxious and lacking trust

Greece’s 14–29s: Ambitious, anxious and lacking trust

-

![Photo by Myrto Papadopoulos [www.myrtopapadopoulos.com] Photo by Myrto Papadopoulos [www.myrtopapadopoulos.com]](resources/toolip/img-thumb/2013/11/05/younggreeks_1000_myrto_0411-small.jpg) Survey charting young voters presents diverse fractures and politics

Survey charting young voters presents diverse fractures and politics

-

![Photo by Can Esenbel [http://www.mundanepleasure.com/] Photo by Can Esenbel [http://www.mundanepleasure.com/]](resources/toolip/img-thumb/2014/02/12/peopleblur_agora_esenbel-small.jpg) Survey attempts to map current contours of progressivism in Greece

Survey attempts to map current contours of progressivism in Greece

-

Greeks crying out for political change but doubt it will happen, poll finds

Greeks crying out for political change but doubt it will happen, poll finds

What brought down Golden Dawn?

The Greek neo-Nazi party Golden Dawn burst onto the parliamentary scene overnight in 2012, to the alarm of democratic forces across Europe. Seven years later, the party finds itself out of the national and the European Parliament after losing more than half its voters.

A lot has happened in the intervening period. Golden Dawn’s leadership remain on trial for forming a criminal organisation and a laundry list of other criminal charges. Greece has completed its economic adjustment programme and exited the tight supervision of its creditors. There have been changes in the political environment, including the resurgence of the traditional centre-right and the emergence of competing ultra-nationalist parties.

While there is undoubtedly cause for celebration in the defeat of Golden Dawn, it is also time to try and identify the key factors that brought its downfall. This is an essential enquiry, as the rise of extreme nationalist or nativist movements continues, and there is a real and present need for any lessons that can be extracted from one the most alarming cases in recent years. We chronicle the rise and fall of Golden Dawn while trying to isolate some of the forces at play in both.

The defeat

Golden Dawn had a catastrophic performance in European and local elections in May 2019. Its support halved compared to the last European contest. From 536,913 votes in 2014, it managed only 275,734 in 2019, while its share fell from 9.39 percent to 4.87 percent. It recorded some of its biggest losses in its traditional strongholds in the Peloponnese, while it also failed to capitalise on the nationalist opposition to the Prespes Agreement in northern Greece. The party elected just one MEP, who resigned from the party within weeks of winning his seat.

The party’s performance in the subsequent national elections was even more dismal. The party has performed better in both European Parliament elections that it has contested than in national elections, both in absolute votes and in percentage terms. However, with the contests held so close together Golden Dawn lost an impressive 110,023 votes on July 7, 2019 – almost a third of its remaining support. In the space of just six weeks, their share plummeted to just 2.93 percent, and narrowly missing the 3-percent threshold for Parliament.

What went wrong for Golden Dawn? Who or what can be credited with cutting one of the most extreme neo-Nazi parties in Europe down to size?

The heights

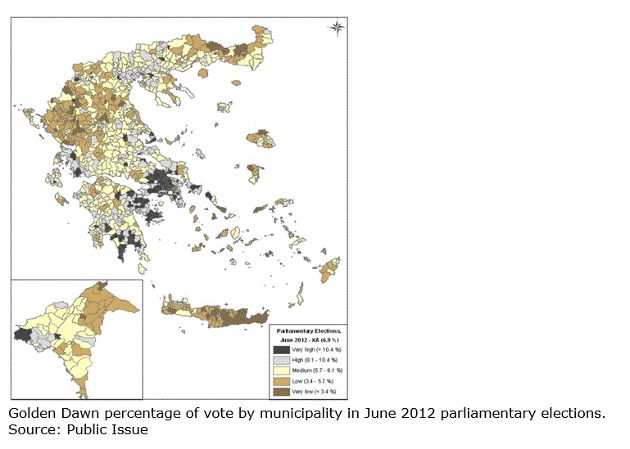

Although Golden Dawn had been registered as a political party since 1983 and contested their first elections in 1994, they only made their mark on the electoral map in 2012. In the aftermath of the protests that greeted the signing of the second MoU, their support in opinion polls skyrocketed from 1.5 percent at the end of 2011 to 12 percent in June 2012. Protest played a pivotal role in amassing this support. Almost a third of their voters in 2012 cited protest, indignation or punishment of mainstream parties as the reason for their choice – this reason led over immigration and border issues (27 percent), patriotism and national issues (13 percent) and the party’s overall agenda (14 percent).

At its height, the party drew its support from two main groups. On the one hand were the traditional conservative voters, found in historical royalist areas in the Peloponnese and central Greece, and on the other hand were the urban poor and the lower middle-class districts of Athens and Piraeus, where high unemployment combined with large concentrations of recent immigrants. The party polled strongly with the young and the unemployed, as well as with farmers, while it was also extremely popular in the security forces.

The trial

Even as the party entered mainstream politics for the first time, its extra-parliamentary activities became both more visible and more extreme, and paramilitary hit squads bearing the party’s insignia were implicated in dozens of incidents of violence and intimidation, including two killings, directed towards immigrant communities and leftist groups. In 2012, one of its MPs hit another deputy on live TV, without any repercussions. However, it was the murder of Greek musician and anti-Nazi activist Pavlos Fyssas in September 2013 that finally crossed a line with the general public and the authorities.

Days after the murder, 22 party members including the party’s leader and its MPs were arrested on charges of forming a criminal organisation, as well as individual charges of murder, assault and money-laundering.

Bringing criminal charges against Golden Dawn’s leadership was not enough in the first instance to shake the support that the party had amassed. Quite the contrary, in the European Parliament elections of May 2014 Golden Dawn received its highest ever number of votes (536,913) as well as its highest ever share of the vote with 9.39 percent. This performance was especially notable given that the party’s leadership was in jail pending trial at the time of elections. The party got just over 10 percent of the vote in Keratsini, the district where Fyssas was killed.

In the January 2015 national elections Golden Dawn polled almost as high as in the 2012 contest with 6.28 percent of the vote compared to 6.92 – and only 37,603 fewer votes. It lost a further 8,806 votes in the next elections in September of that year, but achieved a slightly higher percentage (6.99 percent) thanks to higher abstention, and kept its seats in Parliament.

In the spring of 2015, having exceeded the 18-month maximum period for detention without trial, the party’s leadership were gradually released and allowed to resume their seats in Parliament. Their trial begun in April 2015, and it is only now – more than four years later - entering its final stage with the testimony of the defendants. The trial is expected to end in the autumn of this year, and the prosecution team are confident of securing convictions that will see the key players jailed once again.

The length of the trial process has caused frustration to the prosecution and to campaigners, as well as to the general public. A series of delays caused, among other things, by lack of suitable courtroom facilities, difficulty in obtaining trial dates and lawyers’ strikes added to an already complex case. The defendants were able to employ delaying tactics to avoid testifying with relative ease. While there are no serious accusations of political obstruction (the case was brought under a New Democracy/PASOK government and tried under SYRIZA/ANEL, entering its final stage under New Democracy), lawyers for the prosecution argue that more could have been done to clear some of the logistical hurdles.

If the convictions come to pass, justice in court will come well after punishment at the ballot box. The trial clearly played a part in bringing the party down, but its effect was not straightforward.

Rather than causing instant public revulsion, the prosecution had a catalytic effect on the party’s internal cohesion that was indirect and slow-acting. As a consequence of the charges, Golden Dawn had its state funding frozen, starving it of over a million euros a year (1,272,465 euros in 2018 alone). State funding is intended to support parties’ political activities and research, however Golden Dawn had historically claimed that it was “returning it to the Greek people, mainly in the form of social work, soup kitchens for destitute and unemployed compatriots and families with multiple children.”

According to a former party MEP, when this source of funding was lost Golden Dawn’s elected representatives in the European Parliament were made to pay the party 4,000 euros monthly out their MEP’s salary, while their support staff paid 1,000, both in contravention of EU rules. The same former MEP alleged that the party had amassed up to a million euros from such forced donations, ostensibly destined for its social work, but in practice a slush fund managed by the top echelons without any transparency or accountability.

Having lost all its MPs in the vote and its last MEP to a resignation, the party is in such dire financial straits that it is reportedly struggling to pay the rent on its Athens headquarters.

Golden Dawn was also gradually starved of the oxygen of publicity, as the media who had once hosted their representatives on panel shows and even lifestyle programmes stopped featuring them. Technical staff at the state broadcaster ERT went on strike rather than cover their statutory party-political broadcasts, and social media giants including Facebook and Twitter blocked their official accounts.

The combined pressure from lack of outside funding, increased scrutiny and the distraction of the trial appears to have caused infighting within the party, prompting a series of resignations and defections. These culminated recently in the sidelining of the party’s established MEP candidates in favour of key figures in the trial at the behest of party leader Nikos Michaloliakos. Founding members and popular local cadres openly expressed their dissatisfaction with the leadership, several of them quitting the party on the eve of elections and accusing Michaloliakos and his inner circle of hypocrisy and nepotism.

More than anything, the institutional chokehold on the party appears to have fuelled a succession crisis. As the trial enters a crucial stage, the united front once presented by the defence also appears to be disintegrating, with some of the accused hiring their own legal teams.

Experts warn that even with the upper echelons behind bars there should not be a rush to celebrate the death of the party as long as parts of society remain receptive to their message. However, the rigid militaristic structure which held the party together by discouraging leadership challenges will make it tougher for new leaders to emerge. Having lost a crucial chunk of popular support in advance of the trial verdict, it will be hard for any of the accused party leaders to claim the kind of martyr status that would enable them to continue recruiting followers.

The rival party

It would be tempting to explain the poor performance of Golden Dawn in the latest elections through the emergence of a new far-right party, Greek Solution, which entered both the European Parliament and the national Parliament for the first time this year. Although this looks plausible in terms of simple arithmetic (Greek Solution took 4.18 percent of the vote in the EP elections, compared to the 4.52 percent lost by Golden Dawn), the reality is more complex.

Exit polls from May’s EU elections indicate that only 12 percent of those who had cast a vote for Golden Dawn in September 2015 switched to Greek Solution in May 2019, while 12.6 percent switched to New Democracy and 4.1 percent opted for SYRIZA. Pollsters also point out that Golden Dawn candidates lost up to half of their support even in local and regional elections where they were not facing Greek Solution candidates. This was the case in the district of Attica where their candidate – a prominent GD figure - only attracted 89,141 votes compared to 180,908 votes in 2014, as well as the municipality of Athens where their share fell from 15.12 percent to 10.53 percent, again despite fielding one of their best-known candidates.

In July’s national elections, exit polls showed a further 10 percent of Golden Dawn voters migrated to New Democracy, 6 percent to SYRIZA and 5 percent to Greek Solution.

Rather than supporting the theory that there is a hard core of far-right voters with a stable agenda outside mainstream politics, it would appear that voting preferences in the space targeted by Golden Dawn are quite fluid, and not entirely averse to systemic parties. This mirrors Golden Dawn’s breakthrough elections in 2012, when many were quick to link the party’s emergence with the disintegration of LAOS, the far-right party that had briefly joined the coalition government in 2012. In fact, only 1 in 10 Golden Dawn voters in May 2012 came from LAOS, while 4 in 10 came from New Democracy and 2 in 10 from PASOK.

Even with such an ephemeral base, with large chunks willing to drift back and forth to the mainstream parties of the right and even – to a lesser extent – the left, some of the concerns raised by Golden Dawn are bound to outlive the party itself.

Despite the precipitous fall in its overall support, Golden Dawn was still the third party among 17-24 year-olds in the European Elections, attracting 13.3 percent of the vote in that age group according to exit polls. This suggests that there is a receptive audience for the party’s message among young voters coming of age in the post-MoU era. Meanwhile, the mainstream parties have been complicit in legitimising xenophobic rhetoric, as exemplified by recent innuendo about mass immigrant voter registrations and pledges of benefits “for Greek-born children”.

Anti-systemic, populist slogans adopted at both ends of the political spectrum will also continue to find fertile ground as long as living standards remain depressed. The laws against hate-crimes and hate-speech were not applied consistently enough to combat the activities of Golden Dawn that clearly fell into those categories. Finally, the long-drawn-out nature of the trial, with its myriad of logistical and bureaucratic hurdles, can do little to improve the low levels of trust among Greeks in the judicial system.

Despite all these reasons to be cautious, the salutary message we can take from charting the fall of Golden Dawn is that the trappings of a political party cannot be counted on to provide a protective mantle for those engaging in outright criminal activities.

A necessary precondition was achieving a degree of political consensus, a rare commodity in the turbulent years of the crisis, to apply the rules. The checks and balances afforded by the political and judicial system, however weak and compromised, are what ultimately brought the party to its knees.

![Photo by Myrto Papadopoulos [www.myrtopapadopoulos.com] Photo by Myrto Papadopoulos [www.myrtopapadopoulos.com]](resources/toolip/img-thumb/2013/11/02/goldendawntorches_myrto_1000_011-medium.jpg) Golden Dawn: Forgotten but not gone

Golden Dawn: Forgotten but not gone