-

Great Expectations: Is Greece 2.0 hitting the target?

Great Expectations: Is Greece 2.0 hitting the target?

-

Record year for Greek tourism raises concerns about sustainability

Record year for Greek tourism raises concerns about sustainability

-

What is driving the Greek housing market's recovery?

What is driving the Greek housing market's recovery?

-

Record FDI flow into Greece raises bar, but is it sustainable?

Record FDI flow into Greece raises bar, but is it sustainable?

-

Balance of payments shows shipping on course for bumper year, but economic benefits unclear

Balance of payments shows shipping on course for bumper year, but economic benefits unclear

-

One unicorn does not a Silicon Valley make: positive news on startup front also highlights limitations

One unicorn does not a Silicon Valley make: positive news on startup front also highlights limitations

The first cut is the deepest? Greek pension reforms in context

It is 5:59am on a Sunday morning. The host of the morning talk show, a man of near-pensionable age – a look he has affected for well over a decade – adopts an alarmed look. The caption screams “NEW PENSIONS MASSACRE”. Projected on the backdrop, a dense table of numbers several columns wide defies legibility, and several talking heads are lined up in a panel to argue vociferously and incoherently over how badly pensioners can expect to suffer from the latest spending cuts.

This scene could bear the timestamp of any date from 2010 to the present day, as pension scaremongering has become an integral part of the discourse of the crisis, exciting outrage and despair among the swelling ranks of Greece’s elderly.

Although a burgeoning pension deficit has been the elephant in the room of Greek public finances since at least the 1990s, successive governments have lacked the political will to tackle the issue. It took the financial crisis, and in particular the Memorandum of Understanding that Greece entered into with its lenders in 2010, to kick-start a comprehensive pension reform programme. The programme combines spending cuts alongside a structural overhaul of the country’s sprawling pension system.

Inevitably, the measures have proved hugely controversial, and have been a major focus of public protests against austerity. Often the public rhetoric obscures rather than conveys the situation accurately, skewing the reporting on spending cuts, while rendering the accompanying structural reforms obscure to a public paralysed by fear and uncertainty.

This feature picks up where a 2015 MacroPolis blog post left off, trying to give a more balanced view on a highly charged topic. It reviews some of the impacts of the pension reform programme so far and puts the latest round of measures into the context.

Reforms

The first pension reform package implemented in 2010 was designed to limit the rise of pension expenditure to 2 percent of GDP over the long term (2010-2060). It raised the retirement age and extended the contribution period, imposed an emergency pension freeze and a solidarity levy on the larger pensions. By and large, the measures had little immediate effect on most current pension recipients, apart from those in the top income bracket.

In 2012 more severe measures were taken, including the abolition of holiday bonuses (the so-called 13th and 14th pensions), which affected all pensioners, and additional cuts to the highest pensions, cuts in auxiliary pensions and more. The cumulative cuts ranged from 14 percent for the lowest bracket to over 40 percent for some of the highest.

The most comprehensive reform package was legislated in 2016. This unified all pension funds, including public sector pensions, under a single fund known as EFKA. It abolished all special arrangements, started phasing out the social solidarity benefit EKAS, harmonised contributions and benefits across the board and introduced a minimum state pension. Unlike the 2012 cuts, this reform applied mainly to future generations, while it barely touched those already receiving a pension or those about to receive one, with the exception of those receiving over 1,300 euros monthly in total (around 8 percent of all pensioners).

However, in 2017 new measures were also pre-legislated for 2019, which aim to harmonise the relatively more generous existing pensions with the more modest future ones. These cuts have been capped at 18 percent of main and supplementary pensions. It is estimated that this adjustment will result in an average pension reduction of 14 percent for around a million pensioners out of a total 2.5 million. These latest cuts will be felt immediately by a large portion of existing pensioners and are therefore, once again, highly politically contentious.

Pension expenditure

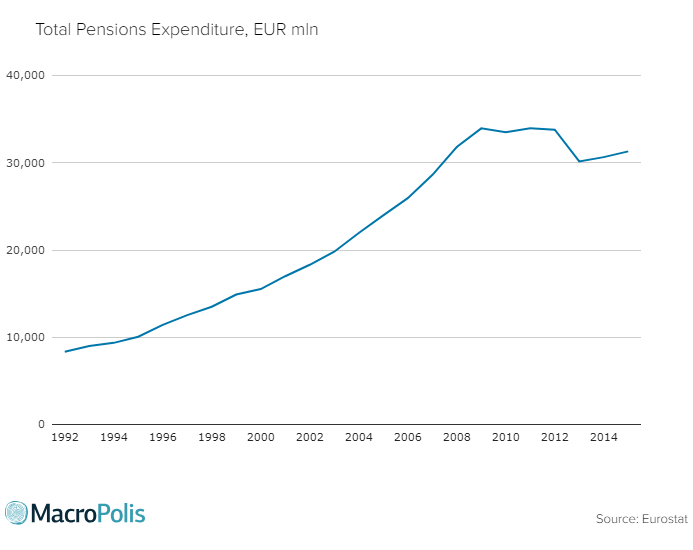

The cost of Greek pensions had been growing steadily since the 1990s, with the expenditure doubling between 2000 and 2008. The combination of the reforms and the ongoing recession halted this trend in spectacular fashion.

Total expenditure on pensions, which is almost entirely dominated by public pension funds, plateaued in 2009, and registered a sharp drop in 2013 as a result of the cuts made in 2012 – a peak-to-trough drop of just over 11 percent. A rush to retirement in 2010-2012 kept the overall expenditure high, even as individual pensions were cut. After 2013, expenditure starts to drift upward again, a reflection of the fact that recent retirees were on more generous packages relative to the bulk of pensioners.

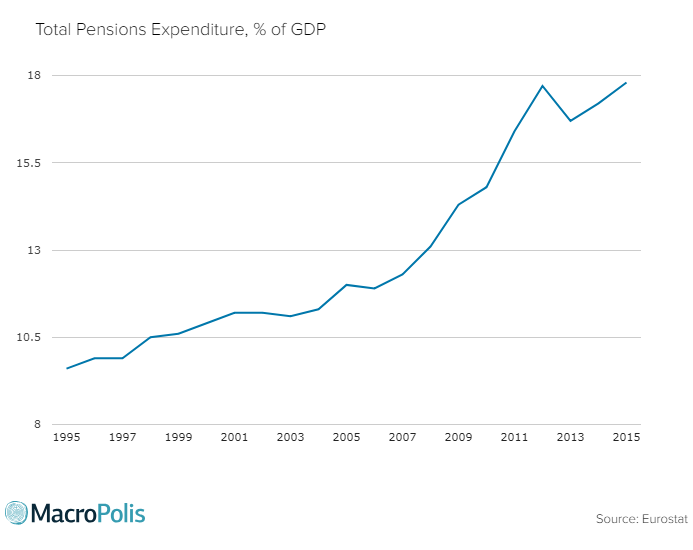

Spending as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), the headline number used in the MoU, continued to increase as GDP plummeted, reaching 17.7 percent by EUROSTAT’s measure in 2012, dropping briefly in 2013 and peaking again in 2015 at 17.8 percent. The European Commission’s projections would see spending on pensions reducing to 13 percent of GDP by 2020, and 10 percent by 2070 as a result of the reforms.

While some have questioned the use of this metric in a deep recession, the counter-intuitive pattern seen above contains a hint that despite the cuts pensions have not taken as big a hit as the overall economy.

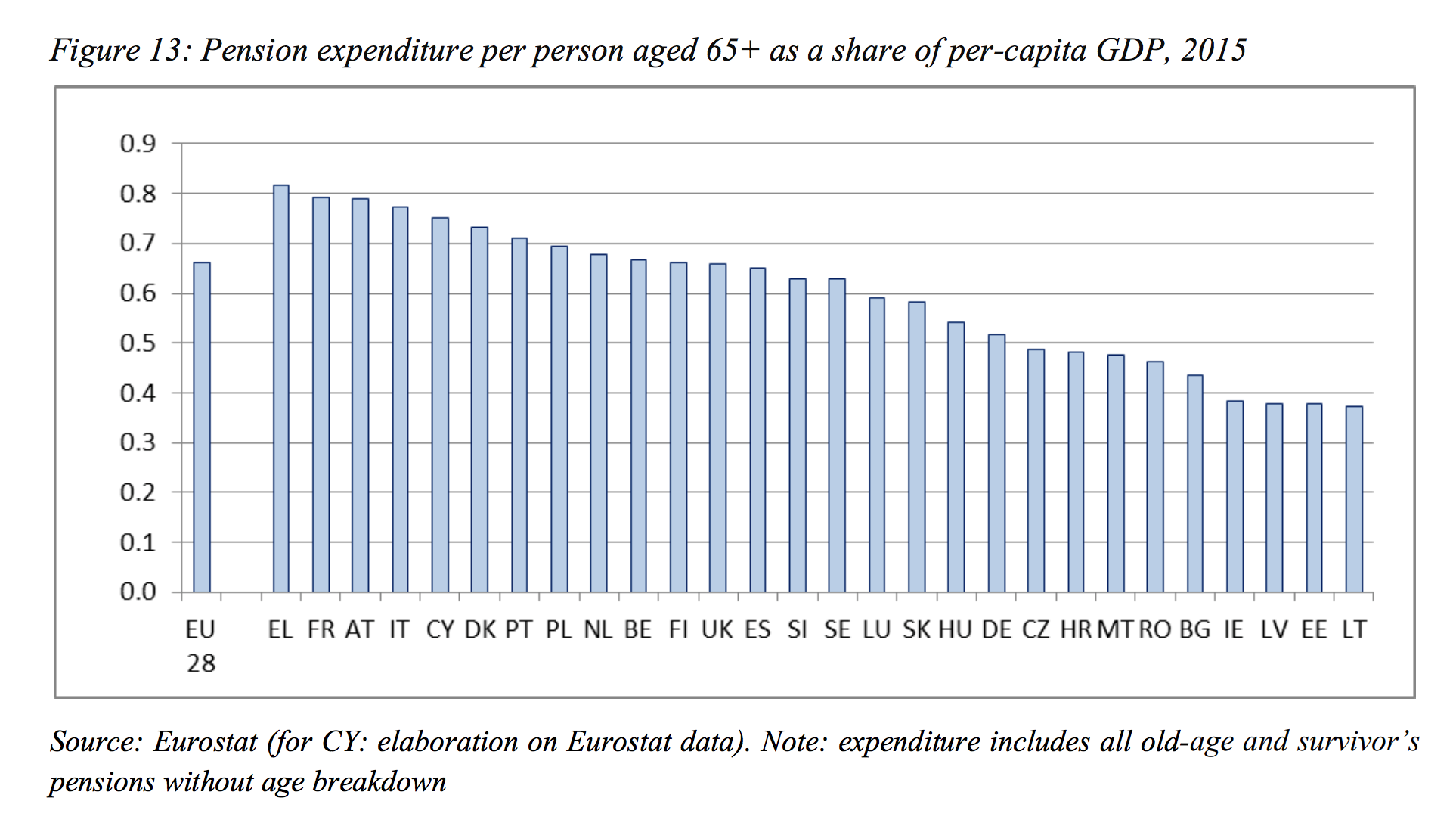

A recent European Commission report on pension adequacy measured pension expenditure as a share of per capita GDP. By this measure, Greece comes top for the relative generosity of its pensions, which are equivalent to 80 percent of per capita GDP, compared to the EU average of around 65 percent. However, by absolute measures, Greece was found to lag in other areas of elder support, with 12 percent of men and 17 percent of women being unable to afford medical examinations, the highest incidence in the EU.

The Greek pension system is funded by a combination of employee and employer contributions, and state funding. The onset of the crisis put a squeeze on all three funding streams roughly within the same time frame, throwing a system already at breaking point into a perfect storm of recession and austerity.

Funding from labour

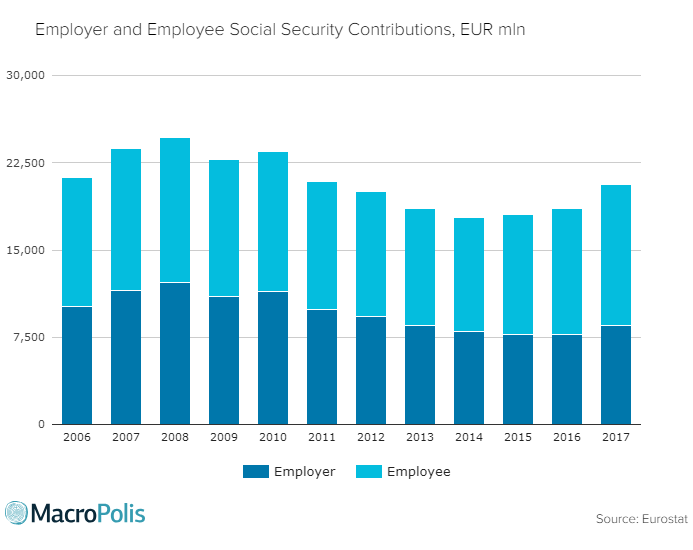

The devastating effect of the recession on economic activity, and the consequent rise in unemployment, put a big dent in employees’ and employers’ contributions into the social security system. In 2008, employers’ and employees’ contributions totalled 24.6 billion euros, while in 2014 that number had fallen to 17.8 million, a decline of over a quarter in combined contributions from labour. This translates into an loss of up to 6.8 billion euros to the pensions system each year, or just under 4 percent of GDP in 2014 terms.

Since that low point, pension finances have been helped by improved collection, increases in contributions linked to the reforms, and a slight recovery in employment levels, which together have edged the amounts paid in by employers and employees back up to an estimated 20.6 billion euros in 2017.

Funding by the state

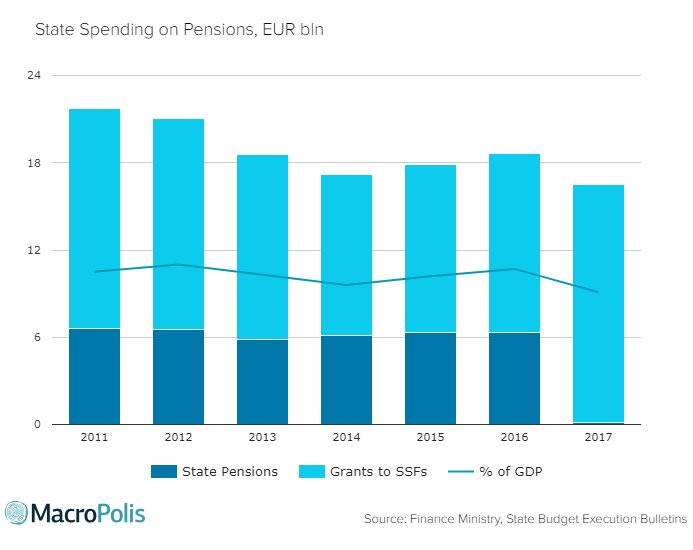

Public pension funds have run a deficit since the 1980s and have historically relied on state subsidies in the form of grants to the various social security funds (SSFs). In 2016, when employers paid 7.7 billion euros and households 10.9 billion towards social spending through their respective contributions, the state topped up spending to the tune of 12.3 billion out of general taxation.

The state has also, until recently, paid its employees’ pensions directly out of the budget rather than through a pension fund. State pensions amounted to 6.3 billion in 2016.

The pensions subsidy is a sizeable burden on public finances, historically more than twice the size of the entire public procurement bill. However successive governments have normalised its existence and latterly downplayed the extent to which it weighed on the economy and ultimately helped to precipitate the crisis.

The cuts have had a measurable impact on state spending on pensions, which has fallen by 24 percent in absolute terms since 2011, and now stands at just above 9 percent of GDP, compared to over 11 percent in 2012.

In 2017, public employees’ pensions were included in the unified EFKA fund, to which the state contributes as an employer as well as through a grant, and the state pension as a separate budget item has been all but eliminated.

Pension levels

The experience for pension recipients has been more varied than is often suggested by the media coverage and political pronouncements, though some of the factoids which peppered the anti-austerity polemic have proved surprisingly resilient.

For example, the oft-repeated statement that “pensions were cut by up to 40 percent” prior to 2015 is very misleading. More than ten pension cuts were implemented between 2010 and 2015, and even the lowest-paid pensioners had their packets cut by 14 percent. However, the majority of retirees lost less of their income than the average working person. Only the top 2 percent of pensioners actually experienced cuts of 40 percent or more.

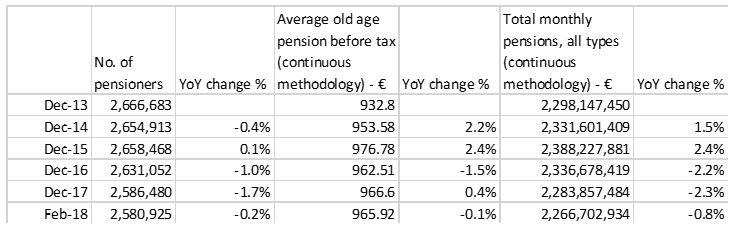

Since 2013, detailed statistics have been published on pension payments – a far cry from the inception of the crisis when SSFs had to conduct emergency audits to track how many pensions were paid and at what cost. Detailed breakdowns allow us to see more granular patterns.

[Source: IDIKA, Ilios bulletins (for consistency, this depiction ignores the change to the methodology in 2015 which affects accounting for health and solidarity withholdings).]

Since 2013 pensioner numbers have stabilised and even show a slight decrease. Following the cuts of 2012, the average old age pension in gross terms has drifted upwards, though the increase has been slightly counterbalanced in practice by the phasing out of EKAS and increased health contributions. The total monthly cost of pensions has been on a downward trend since 2016.

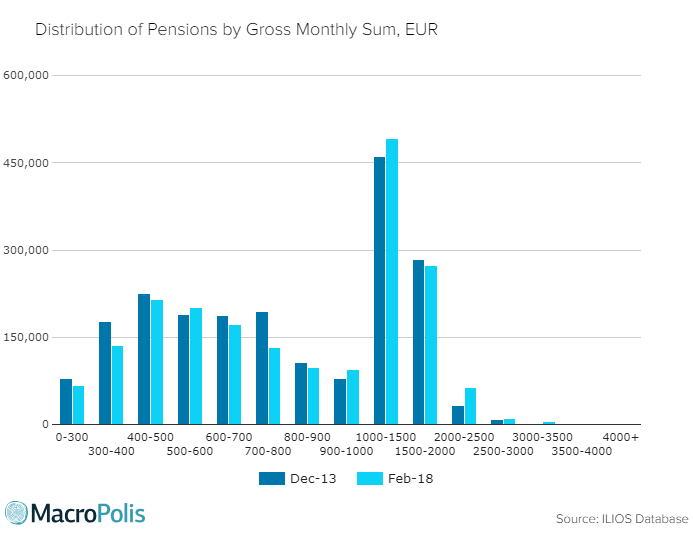

There has in fact been a slight shift in the distribution of pensions from the lower- and middle-income brackets to the higher ones, reflecting the higher cost of more recent pensions (those not affected by the 2016 reforms).

It is these higher brackets that will be most affected by the upcoming cuts, though not as severely as the first phase of cuts, thanks to the 18 percent cap.

Need

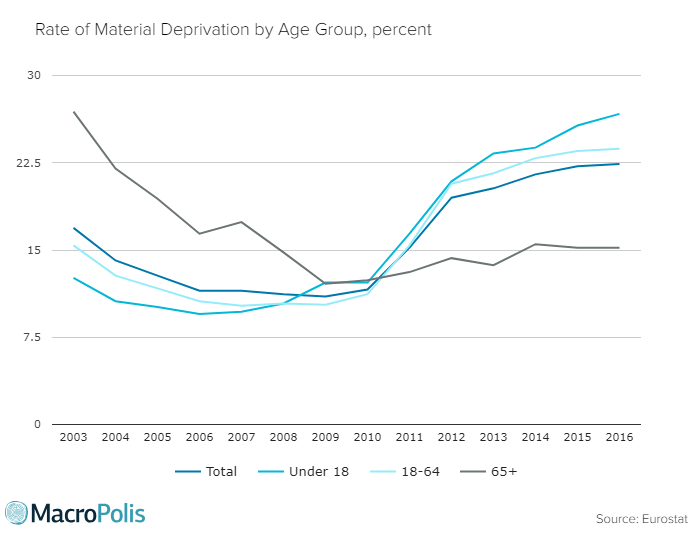

A loss of income upwards of 14 percent will undoubtedly have a serious impact on living standards. However, the coverage devoted to pensioners often obscures the effect that the crisis has had on other social groups, which is often more severe.

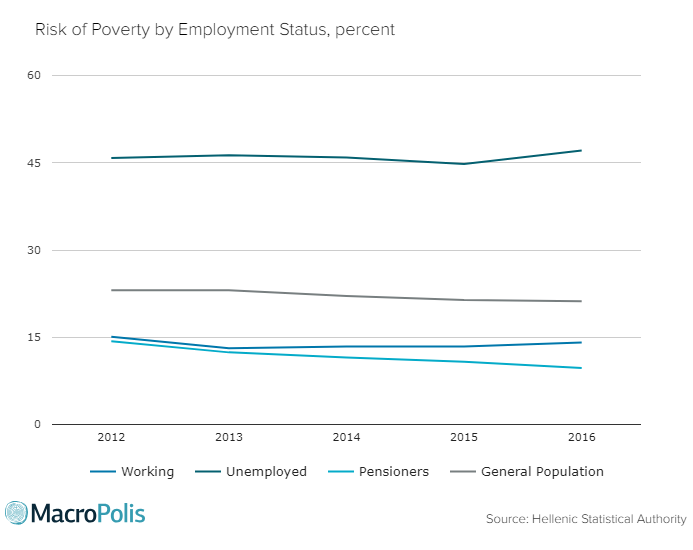

Measures of poverty, in both relative and absolute terms, reveal a very similar pattern as the recession has progressed: the old and the pensioners have been much more cushioned from the crisis than those of working age, and particularly the unemployed.

Whereas prior to the crisis more pensioners were lacking essentials than any other social group, the pattern is now reversed, with the young now being the most deprived.

Fewer pensioners are falling below the poverty threshold (defined as 60 percent of the median income) than all other employment categories (including those in work).

Fewer pensioners meet the definition of extreme poverty than any other employment category, with the exception of public sector workers.

This is not to ignore the fact that living standards have worsened for everyone. The poverty threshold has falling as the median income declines, so a higher percentage pensioners would fall below the 2009 poverty threshold, as would a larger portion of other groups. But in terms of determining national spending priorities, this tells us that the policy response has shielded pensioners more than other social groups.

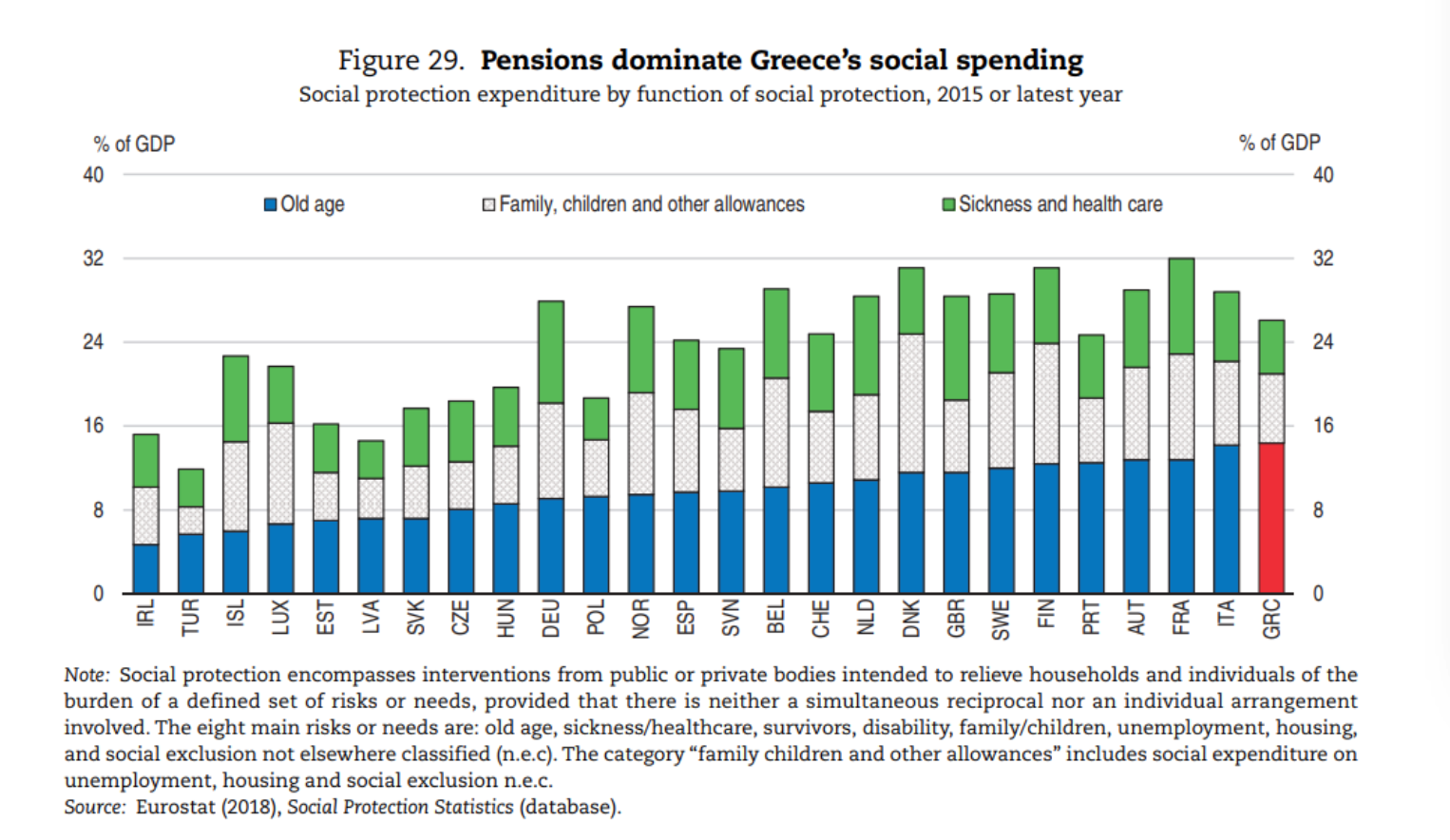

This reflects a long-standing pattern in Greece, whereby social spending has been directed overwhelmingly through pensions rather than other forms of social support, such as unemployment, healthcare, housing or childcare benefits. This was highlighted in the latest OECD economic survey of Greece, in which the country came top in terms of the portion of social spending devoted to pensions. The report advocated more balanced social spending, with more directed towards young families, combined with active labour programmes to get more people into employment.

[Source: OECD]

Pensions have long been seen as the ultimate safety net, with younger generations receiving benefits in the form of “pocket money”. The crisis has only accentuated this effect, as a recent survey showed that for just over half of all households in Greece rely on a pension as their main source of income.

In a surprising defence of what is essentially a regressive status quo, the current Labour Minister Efi Achtsioglou cited the high dependence on pension income as an argument for rethinking the impending pension cuts, while more minor government figures have been drip-feeding hints of a post-MoU relaxation to a desperate domestic audience almost daily.

In fact, surprisingly little has been made, even by the government that negotiated it, of the broader policy package around the upcoming pension cuts. The pre-legislated fiscal measures for 2019, which appears to have survived into the draft Supplemental MoU, also includes a spending package to match the 1 percent GDP in pension cuts.

The spending is earmarked for housing allowance, child benefits, school meals nursery and pre-school education, means-tested reduction in health co-payments (totalling 0.7 percent of GDP), public infrastructure investment (0.15 percent of GDP) and active labour market policies (0.15 percent GDP) – in other words targeting the groups most affected by the crisis. While the package is admittedly conditional on the government meeting its targets, its adoption would will be a small step towards distributing social spending more equitably, and perhaps more productively.

Demographics

It is often openly claimed - or casually implied - that the main aim of pension reform is to generate the 3.5 percent primary surplus demanded by the MoU. That is only part of the truth, the other part of which is less politically palatable. The reforms as expounded in the successive MoUs have been aimed principally at making the pension system sustainable over the next 50 years. Even in the absence of the financial crisis and the creditor’s lending terms, pension reform was needed because the system as it existed up until recently is unfair and unsustainable, and demographic trends are making it even worse.

Greece currently has the highest rate of economic old-age dependency in Europe, according to the latest report on ageing by the European Commission. The ratio of inactive elderly people to the number of employed is currently 62.6 percent in Greece, meaning that there are three retired people for every five workers, compared to a ratio of 43 percent in the EU (roughly two retired people for every five workers). By 2070, the ratio is projected to grow to over 81 percent for Greece (four retirees for every five workers), compared to 68.5 percent for the EU.

Even if employment were to return to pre-crisis levels, the demographics are punishing. Greece has 3 people over 65 for every 10 of working age. According to the OECD’s projections, that number will have doubled by 2050. Most pension systems globally are having to adapt to some version of this reality, but the finances of the Greek system made this need all the more urgent.

Whether the current reform programme is the most effective for addressing these challenges is open to question. In the absence of an open and honest debate on the subject, there is a dearth of alternative proposals to what has been adopted as part of the economic adjustment programme.

The reformed system has many evident weaknesses – for instance, it continues to assume that the dominant form of employment is long-term and full-time, something that is clearly not the case. The fragmented system of niche pension funds has been replaced with a highly centralised a one-size-fits-all approach. It is worth asking whether this is the right model for the future. Sadly, there is very little indication that these questions will be addressed any more seriously after Greece’s exit from the programme than they were before.

Politics

Given the massive implications of the pensions timebomb, it is ironic - though perhaps not surprising - that the political establishment continue to perpetuate narratives that resist any moves for reform.

The fragmented pensions system has long been a conduit for political favours, allowing the cultivation of special interest groups and political clienteles. Any elected government attempting to dismantle the cat’s cradle of occupational pensions, special deals and protected privileges would soon feel their political existence threatened.

It is also abundantly clear to all political parties that what’s good for the pension pot could spell disaster at the polling booth. While the general population is ageing, the voting population is skewed even more heavily towards the pensionable age group. Pensioners made up by far the biggest voting group in the last general election in September 2015 – estimated at just over a quarter of voters - while almost four in ten voters were over 55. As in most western democracies, older voters persist in turning out to vote, while younger voters are more prone to abstention. The last contest showed the over 55 group to be a political battleground, with almost equal numbers voting for SYRIZA as New Democracy – a radical swing that was clearly influenced by the younger party’s promises to preserve pensions against the establishment’s party’s record of cutting them.

In this context, painting pension reform exclusively as an austerity policy imposed by the country’s lenders is as politically irresistible as it is short-termist and damaging to the public interest. In choosing this path - even at the eleventh hour of the crisis - Greece’s political parties have forgone the opportunity to engage on their own terms in addressing a known and serious public policy issue affecting future generations.

New round of cuts in supplementary pensions

New round of cuts in supplementary pensions  Pensions continue to be main source of income for half of Greek households

Pensions continue to be main source of income for half of Greek households  Concerns raised about next year's pensions cuts

Concerns raised about next year's pensions cuts