-

Podcast - Subsidise this: Fraud scandal delivers new blow to Greek PM

Podcast - Subsidise this: Fraud scandal delivers new blow to Greek PM

-

Fet-a-ccompli: Tariffs and Greece’s big cheese

Fet-a-ccompli: Tariffs and Greece’s big cheese

-

Athens and Berlin have reasons to take a closer look at each other

Athens and Berlin have reasons to take a closer look at each other

-

Minimum wage increase crashes against reality of Greeks' low purchasing power

Minimum wage increase crashes against reality of Greeks' low purchasing power

-

Podcast - Greek politics feels aftershock from Tempe train crash

Podcast - Greek politics feels aftershock from Tempe train crash

-

Podcast: Greece, Europe and the new world reordering

Podcast: Greece, Europe and the new world reordering

Jobs, hundreds of thousands of jobs

![Photo by Myrto Papadopoulos [www.myrtopapadopoulos.com] Photo by Myrto Papadopoulos [www.myrtopapadopoulos.com]](resources/toolip/img-thumb/2013/10/12/indignant_myrto_1000_1210-large.jpg)

Jobs, jobs, jobs. Promises of jobs by the hundreds of thousands were flying around in the public debate in Greece over the last couple of days. Deputy Prime Minister and PASOK leader Evangelos Venizelos suggested that around 920,000 jobs could be created in the next few years when he presented the party’s growth plan out. Prime Minister Antonis Samaras was a bit more conservative but equally generous when he pledged the creation of 770,000 jobs between now and 2020.

Greece has been under the troika’s cosh for exactly four years. The most devastating cost has been the loss of 1 million jobs. The unemployment rate peaked in September last year at 27.7 percent and the latest reading for February 2014 was at 26.5 percent. At the same time, the number of people in employment has decreased by more than 20 percent. Greece’s labour market has been devastated, like no other in any modern crisis.

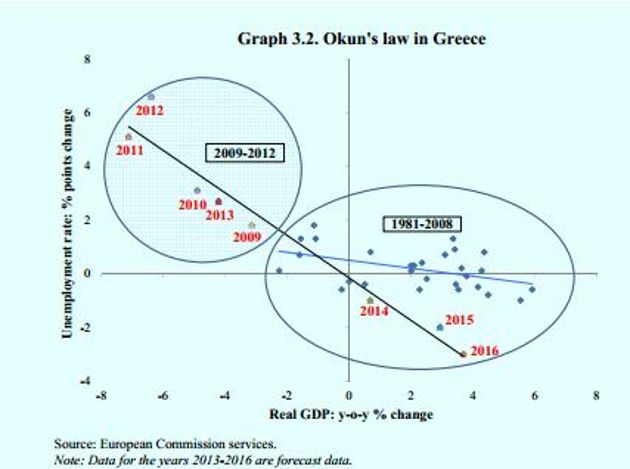

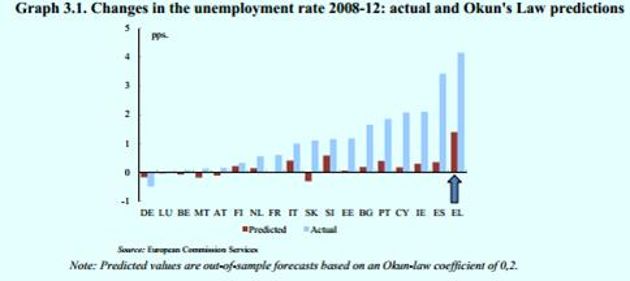

According to the troika’s assessment, most particularly the European Commission, the deep wounds left by the crisis have changed in Greece the relationship between economic growth and changes in the rate of unemployment, what is known as Okun’s law.

Over the last four years, Greece shifted from a relationship in which even high levels of growth had little impact on unemployment reduction (period 1981-2008 above) to a much steeper relationship (period 2009-2013) that saw the unemployment rate increasing by an average of 0.75 of a percentage point (pp) for every pp of GDP lost. The relationship peaked in 2012 when a 6 pp reduction of economic activity led to unemployment increasing by over 6 pp.

Everyone involved in the design of Greece’s policy and economic planning seems to have adopted this new steeper relationship between growth and unemployment, believing unemployment in the coming years will be reduced by over 1 pp for every pp of growth. The problem here though is that this relationship is not an exact science.

GDP and unemployment might indeed move on the new path but growth might be lower and this could lead to the decrease in unemployment being less pronounced. Or, as was the case in all European countries over the last five years, the shock might be so severe that the relationship changes and Okun’s Law fails to predict that rise in unemployment by a wide margin. There is no reason to rule out that Greece might return to the old relationship and end up in a jobless recovery.

However, even if we accept that this assumption will hold, the promise of 770,000 jobs in the next six years made by Samaras is still problematic.

Assuming a more or less stable labour force in the region of 4.9 to 5 million, 770,000 workers represents 15.4 percent of the labour force. To get this number of people back into employment over the next six years will require, based on the official assumption, approximately 15 percent of economic growth and an increase in GDP from 180 billion euros in 2013 to 207 billion by the end of 2020. This implies growth will never drop below 2.5 percent of GDP on average. That is pretty ambitious and everything needs to go like clockwork. How likely is this when Greece is an economy three quarters of which depends on consumption, where investment has evaporated and liquidity still remains elusive? Meanwhile, deflation in wages and prices of domestically produced goods is a policy choice to regain competitiveness but exports have failed to pick up. On top of that, the government will remain a drag on the economic identity, having to find additional savings through reduced spending even up to 2016.

Even the breakdown of job creation by each sector provided by Samaras seems unconvincing.

He suggested that tourism will bring in 225,000 new jobs by 2020 when the accommodation and food services sector employs 253,300 people at the moment. This represents just over 7 percent of employment and even at the country’s employment peak in Q3 of 2008 had 86,200 more jobs, employing 339,500 people in total. Even though Greek tourism is on the rise, it is overly optimistic to assume that a mature industry as such will essentially double its employment in a handful of years.

Equally, Samaras said the primary sector (agriculture, fishery) and packaging is expected to bring in 315,000 jobs, which is an increase of more than 70 percent from the current levels of around 440,000 jobs. It is a pretty generous assumption to expect 50,000 jobs a year on average to be created in such a short timeframe.

These two sectors alone make up of three quarters of Samaras’s employment pledge, which is also questionable in other sectors, where employment is expected to increase by sizeable margins and surpass previous peaks.

It is also worth considering that the premier does not have a good track record on employment pledges. He promised more than 100,000 jobs would be created in his first full year in office but instead employment has fallen by over 140,000 jobs since he took charge.

Admittedly, Greece’s economy has hit rock bottom and is set to begin a gradual recovery. But it is some leap to go from this to claiming abundant job creation in an economy which has seen its productive capacity destroyed and business investment reduced by 60 percent. Even then we have to take into account that just under one million of those without a job are long-term unemployed, the country is suffering a brain drain via immigration of its skilled labour force and there is a serious risk of skills mismatch in the labour market.

As much as foreign investment is a useful tool to stimulate growth in an open economy, it is its domestic saving rate, capital accumulation and technological progress that are the prerequisites for a higher level of GDP and sustainable economic growth. Greece at this point is seriously suffering on all three accounts. To imply that its economy will magically become a tiger in the next six years and will create jobs annually in the hundreds of thousands lacks a serious scientific basis.

Of course, five days before the highly politicized European Parliament elections, Samaras and Venizelos’s pledges may not be based on science but instead on the typical pledges they and their generation of Greek leaders are familiar with: “Θα σας εξασφαλισομεν,” or “We will look after you.”

*Yiannis has contributed extensively over the last two years to the debate around the Greek crisis and the events in Cyprus through his blog The Prodigal Greek, which earned him a place in the esteemed group of Emergency Specialist bloggers, according to FT Alphaville. If you appreciate strong views and economic charts look out for Yiannis in The Agora. Follow Yiannis: @YiannisMouzakis

1 Comment(s)

-

Posted by:

"it is its domestic saving rate, capital accumulation and technological progress that are the prerequisites for a higher level of GDP and sustainable economic growth."

Given that the minimum wage (applied to all sectors including high skilled and technology) is presently at 580€ pm for adults and 530€ pm for under-25s - BEFORE taxes - and is set to be cut by ND after the EU election, and further cut under EU's mandate for wage cuts/competitiveness....

and given that it is at present impossible in Greece to live on this wage, due to the high cost of goods, services and utilities,

the domestic savings rate and capital accumulation among ordinary greeks (including salaried professionals) is a Dead Duck.