2014 is not 2012

Since the eurozone crisis kicked off towards the end of 2009 in Greece there has been no other institution that has gained in prominence like the European Central Bank.

Aside from the fact that it became part of the awkward arrangement with the European Commission and the International Monetary Fund to oversee the programs of Greece, Ireland, Portugal and eventually Cyprus, the central bank held the ultimate leverage on countries across the eurozone, the provision of liquidity to the their banking systems.

The dependency on the ECB started with the financial crisis in 2008, when liquidity for banks dried up everywhere else and the Frankfurt-based lender stepped in with various discount windows. As the eurocrisis unfolded, different countries found themselves with weak banking systems for different reasons and their banks resorted to the Emergency Liquidity Assistance, the famous ELA.

Banks turn to ELA when they don't meet the criteria of the standard financing operations of the ECB. ELA is provided by the national central bank and is regularly reviewed and thresholds approved by the ECB. ELA is effectively the lifeline for banking systems and that makes it the ultimate lever to ensure either compliance or control of developments.

It is this leverage that then ECB-governor Jean-Claude Trichet used to coerce Ireland into a programme that did not include burning Irish banks’ senior bondholders. In May 2011, he sent out a similar letter to Greek Prime Minister George Papandreou, advising that a strategy of debt restructuring would mean that Greek banks will not be able to use Greek government bonds as collateral to secure liquidity from the ECB. In March 2013, Cypriot President Nicos Anastasiades was given an even harsher ultimatum that the island's two banks would lose access to ELA within a few days, effectively leaving the country without a banking system and out of the euro, if he did not agree to a bail-in.

The euro area’s central bank turned from the monetary authority with a price stability mandate into the most powerful conditionality enforcer, even more powerful and convincing than the fearsome IMF.

As Greece's latest review drags on after a series of terrible tactical and awful strategic decisions by Samaras over the last six months, the issue of Greek banks and access to ECB liquidity is coming up again due to the bank’s position that without a program in place it will not accept Greek government bonds as collateral and local lenders will be forced to the more costly ELA.

Taking a closer look, though, much has changed for Greek banks and their relationship with the ECB since the peak of the crisis.

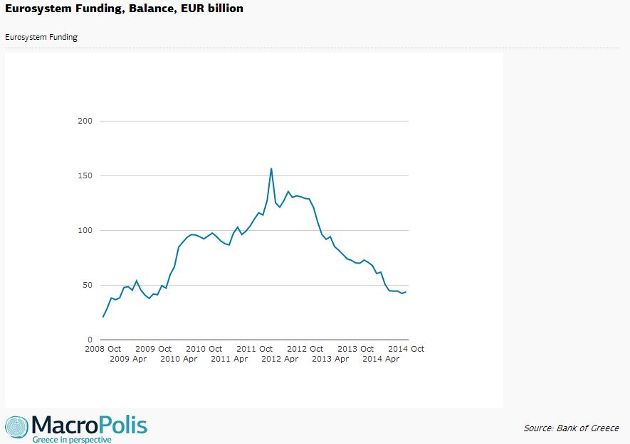

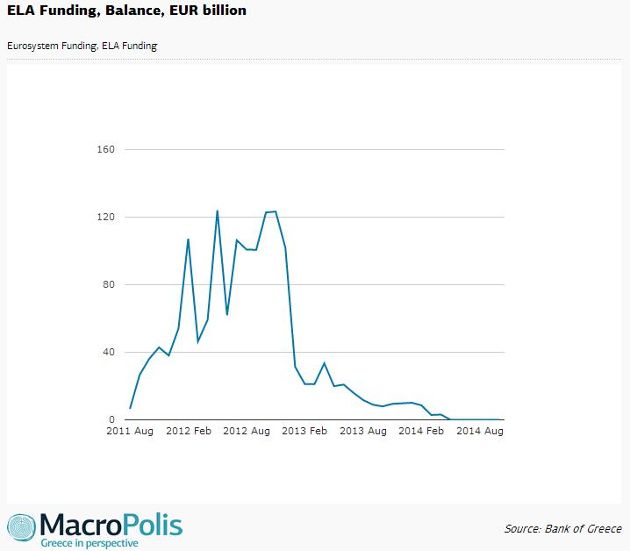

Greek banks entered the global financial crisis with eurosystem funding of 20.6 billion euros in October 2008, one month after the collapse of Lehman. The ECB dependency peaked in February 2012, with just over 157 billion. Of this, 107 billion was from the ELA, the emergency assistance that became available to them from August 2011, a month after the discussion about restructuring Greek debt on a 20 percent net present value basis began.

ELA dependency peaked in May 2012, the month of the first round of general elections, reaching 124 billion euros. Since November 2012, Greek banks resumed access to ECB financing operations, which naturally reduced their ELA dependency until it was entirely eliminated in May this year.

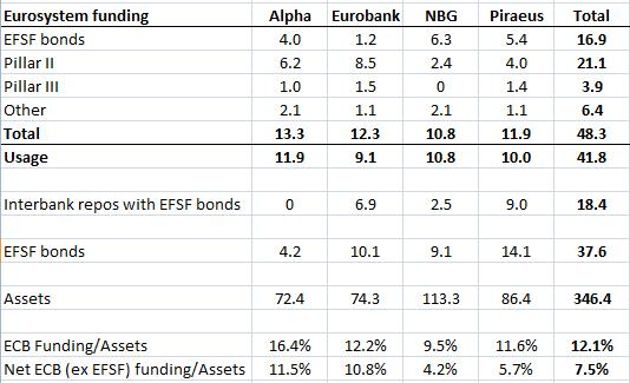

Greek banks have significantly reduced their ECB dependency over the last few months and it now stands at below 44 billion euros, as low as it was back at the start of the Greek crisis in November 2009. Overall, total eurosystem funding is 12.1 percent of the combined 346.4-billion-euro balance sheets of the four systemic banks. When the round of state recapitalisations started two years ago, the target was to bring eurosystem dependency below 15 percent of the combined balance sheets in 2017, a target that was easily achieved three years ahead of time.

Another factor often missed is that Greek banks do not hold any more Greek government bonds in the conventional way. Their last holdings after the Public Sector Involvement were contributed in the debt buyback at the end of 2012, the most recent effort to reduce Greece's debt.

Greek banks are using Greek state guarantees as collateral for ECB liquidity as part of the bank support schemes known as Pillar II and Pillar III. According to their latest results, a combined 25 billion of those state guarantees is currently used as collateral with the ECB. Although it is a decent chunk of the pledged collateral, Greek banks would have to deal with this problem in the near-term anyway, since these state guarantees will no longer be eligible for financing operations from the 1st of March 2015.

Additionally, Greek banks were recapitalised with best quality paper in the eurozone: EFSF notes. They have just under 37.6 billion euros of EFSF notes in their books, circa 17 billion euros of those are already being used for ECB financing operations and more than 18 billion for interbank repos. There is the possibility of redesigning liquidity operations and releasing further EFSF notes for collateral with the ECB if required.

Finally, the massive ECB dependency during 2011 and 2012 was because the system lost 87 billion euros of deposits (around a third of total savings) between December 2009 and May 2012. Although only gradually, the trend has reversed and 14 billion euros have returned to the system.

As much as nobody should suggest that Greece has anything to gain from the uncertainty caused by prolonged troika negotiations, it is clear that circumstances relating to the country’s banking system today are different than they were a few years ago: 2014 is not 2012.

Follow Yiannis on Twitter: @YiannisMouzakis

Podcast - Whose property? Greece’s housing challenges

Podcast - Whose property? Greece’s housing challenges Can the Green Transition be just?

Can the Green Transition be just? Where is Greek growth coming from?

Where is Greek growth coming from? Bravo, Bank of Greece

Bravo, Bank of Greece