Greek pensions laid bare

Greece’s pension system is taking centre stage again in the discussions with lenders. It should come as no surprise that even five years of programmes and repeated interventions have not managed to deal with the monster that was created after decades of mismanagement and a misled belief of entitlement.

The first alarm bells regarding its sustainability rang in early 1990 when it become obvious that the re-distributive nature of the Greek pension system – the contributions of those in employment paying for the pensions of those retired – would face serious headwinds as the ratio of employed per pensioner was steadily declining and the demographics were developing unfavourably for a rather generously designed scheme.

A comprehensive report on the Greek pension system in 1997 highlighted all the risks and gave a small window of opportunity up to 2005 to deal with the issue before the pension rights of older generations would come to maturity and put significant strain on the financing of the system and consequently the state budget.

No government since that report took the courageous step to deal with the issue head on and upset reluctant stakeholders and social partners. There were half-hearted patch ups involving minor, mostly parametric, interventions.

An attempt at reform in 2001 by the then PASOK government met serious social and political resistance and was quickly abandoned due to fears about the political cost and ambition for re-election. This left the Greek political system continuing to finance the system through deficit financing and, while society remained oblivious or refused to face the uncomfortable truths.

Absence of genuine intention to reform created a skewed pension system which was heavily reliant on state grants. According to Eurostat data (courtesy of Emmanuel Schizas's recent blog post), in 2009 when employer contributions were just over 11 billion euros and 11.7 billion euros came from contributions of employees and the self-employed, the state was by far the biggest donor in the system, paying in 17.8 billion euros.

When the Greek state found itself effectively bankrupt in 2010, the system was almost in a state of decay, not knowing exactly how many pensions were actually paid. It was a natural consequence that pensioners became prime candidates to feel the effects of the painful belt-tightening that would ensue.

Since the start of the crisis Greek pensions have been a fertile field for populism and misleading reporting. In this heated and highly emotionally charged debate on the topic, we attempt to present some figures that highlight what has been done so far on the fiscal front and what is the current state of play.

State contributions

The state budget covers public sector pensions (main and supplementary) as well as providing grants to the social security funds (SSFs) to also cover the payment of private sector pensions.

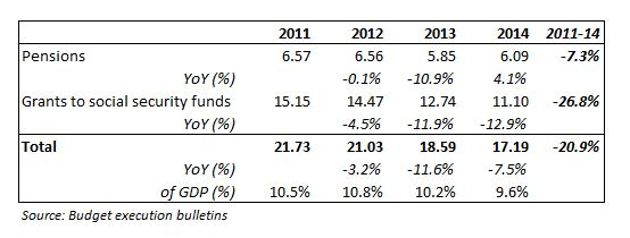

In 2014, the state pension bill reached 6.09 billion euros and state grants to SSFs stood at 11.1 billion. The combined total corresponded to 9.6 percent of GDP.

Despite a sharp drop of 21 percent (4.5 billion) in the total figure since 2011, the respective figure relative to GDP has fallen by just 1 percentage point. This reflects the fact that GDP contracted by around 14 percent over this period.

The biggest annual drop was recorded in 2013 when the full impact of the last pension cut and abolition of bonuses (Christmas, Easter and holidays) voted in 2012 became effective.

The grants to SSFs serve a varied role. Aside from plugging funding holes in various pension funds, in 2014 the state covered health-related expenses of 656 million euros for the main healthcare provider (EOPYY), a figure which is almost half the 1.1 billion that was spent in 2013.

The Manpower Employment Agency (OAED) received 431 million euros last year, from 477 million in 2013, to cover unemployment benefits and subsidized employment schemes.

The Complementary Pension Allowance (EKAS), which serves more as a benefit for low-income pensioners rather than retirement pay, reached 721 million euros last year from just under 800 million in 2013.

The lion’s share of actual pension-related grants goes to the farmers’ insurance fund (OGA) and the wage earners’ fund (IKA) with each receiving grants of around 2.9 billion euros in 2014. They are followed by the fund for the self-employed (OAEE), which although reduced from the 1.4 billion of 2013 still required 1.1 billion last year.

The state’s contribution to the two funds associated with the Hellenic telecommunications (OTE) and public power company (DEH) is close to 1.2 billion euros.

Pure pension-related grants, excluding EKAS, from the budget were under 9 billion, or 5 percent of GDP, in 2014

The state’s total contribution to the social security sector in 2014 reached 14.4 billion euros, almost 8 percent of GDP, from just under 16 billion in 2013 and served a varied role. It includes the national health system by covering the operational deficits of hospitals with almost 1.5 billion euros, 1.8 billion euros was spent on social protection, including the 500 million “social dividend” distributed by the previous coalition government led by Antonis Samaras.

Public sector pensions

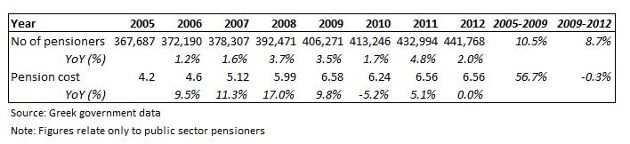

Two years ago, Samaras’s government submitted a document in Parliament showing the evolution in the number of public sector pensioners and the related pension cost since 2005. The data indicated that in the 4-year period until 2009, although the number of pensioners rose by 10.5 percent, the public sector pension cost climbed by 56.7 percent, to 6.58 billion in 2009.

Since then, although the nominal pensions were slashed, the total cost remained virtually unchanged in 2012 as the number of pensioners increased by 8.7 percent over this period.

Pension costs

The latest official figures provided by the social security system’s online service (IDIKA) for March 2015 indicate that 2.9 million main pensions were paid with a monthly cost of 2.07 billion euros, implying that the average main pension is 713 euros. The figures show that almost 76 percent of main pensions stand below the 1,000-euro mark.

In addition, 1.64 million supplementary pensions were paid in March with a cost of 277 million euros, which corresponds to an average supplementary pension of 169 euros.

Extrapolating the March total pension figure of 2.35 billion euros, we get an annual figure of 28.2 billion. The bulk relates to main pensions (24.8 billion), the total annual cost for supplementary pensions whilst is 3.3 billion. The total annual figure corresponds to 15.7 percent of GDP.

Overall, for the total of 2.65 million pensioners in Greece the average monthly income from pensions amounts to 884 euros.

Note, though, that for around 45 percent of pensioners their monthly pension income stands below the 2013 poverty limit of 665 euros.

Age breakdown – early retirements

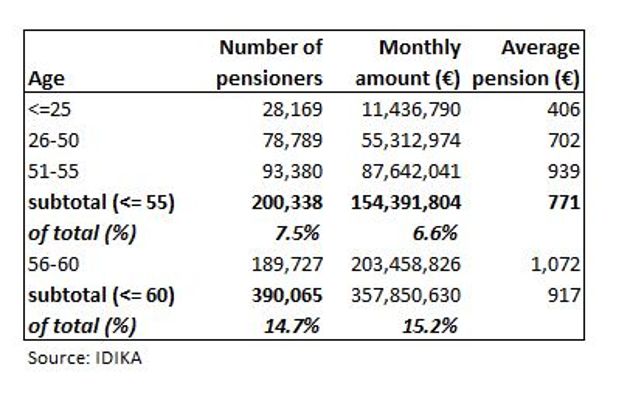

The breakdown by age shows that 7.5 percent of current pensioners are below 55 years old and they receive on average monthly pensions of 771 euros. This is below the overall average of 884 euros since a large part of these cases relate to early retirement, which results in lower payouts. Another 7.2 percent of pensioners is between 55-60 years, meaning that almost 15 percent of current pensioners are under the age of 60.

In its latest proposal, the Greek government suggests gradually limiting early retirement so nobody can claim a pension before they reach 62. This adjustment would be phased in from the beginning of 2016 until 2025.

The government’s document outlines that the average retirement age in the public sector currently stands at 56.3 years and will gradually increase to 60.7 in 2022 and further to 64.4 years in 2025.

For the private sector, the starting point for the average retirement age stands at 60.6 years in 2016 expected to reach 64.3 in 2022 and 65.1 in 2025.

This suggests a more rapid adjustment is scheduled for the public sector where the current average retirement age is four years below that of the private sector and reflects the lower retirement age for armed forces as well as the early retirement of female public servants when they are over 50 years old and have a child below 18.

Pension fund assets

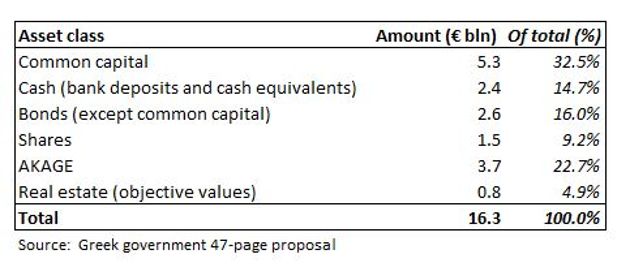

The assets of pension funds have been a bone of contention during the crisis. Due to legal restrictions, the funds had invested large parts of their assets in Greek government bonds, even in the run up to the Private Sector Involvement (PSI) in March 2012 and took a major hit when the debt swap took place. According to data from the Finance Ministry, pension funds lost approximately 12 billion euros as a result of the PSI.

At the end of 2014, pension funds’ total assets amounted to 16.3 billion euros, with almost one-third in common capital, while the wealth of the Generational Solidarity Insurance Fund (AKAGE) stands at 3.7 billion, corresponding to almost 23 percent of the total.

Given the amounts required to keep the Greek pension system functioning in its current form, It is evident that even factoring in the PSI losses, Greek pension funds assets do not have the capacity to support the retirement pay under any type of asset management.

Greece’s pension system still has room for improvement and reform. It is crucial that there is a clear distinction in its functions between social security and welfare. It needs to ensure there are adequate financial resources to support the health system as an extra safety net. It can redirect financing to true welfare and social protection functions which are not linked to pensions and can at the same time secure a respectable minimum level of living.

Most critically, the overall mentality regarding Greek pensions needs to be redirected from the re-distributive to the capitalised, in which the individual will take ownership of his/her own retirement planning. This would put an end to people having false expectations from the state, while securing a respectable level of income for people in their old age.

From what we understand, in these five months of negotiations there has been resistance to a comprehensive overhaul of the system on one side and a fixation on fiscal targets on the other. Neither side is doing justice to the idea of pension reform.

6 Comment(s)

-

Posted by:

I find it incomprehensible that there should be 28,169 pensioners under the age of 25 and another 78,789 under the age of 50. How can this be, and what justification is there for it?

With the combination of an ageing demographic and falling birth rates, Greece is not alone in sitting on a pensions time-bomb; it's a factor in every major economy. The whole business of early retirement is, and always was unsustainable, and is an issue which Greece should have addressed years ago.

The other issue that Greece needs to address if it is ever to climb out of recession is the Byzantine bureaucracy that ties potential entrepreneurs up in reams of red tape for so long that many are inclined either not to bother or alternatively to operate outside the system, thus depriving the government of taxes. There needs to be a clean sweep, a hurricane of reform throughout the civil service. The public sector is essentially unproductive (not just in Greece but everywhere), and needs to be kept to a minimum, while entrepreneurship needs to be encouraged with simple and easily effected rules and regulations that can be complied with in days rather than months.-

Posted by:

The number of pensioners under 25 corresponds almost exactly with the number of people suffering from thallasaemia, a genetic disease that is especially prevalent in Greece where it affects 1/400 people. Patients rarely survive past their 30th birthday. Strictly speaking this is welfare, but in the Greek system it is dispenced through the pension administration.

-

-

Posted by:

I wish this this excellent review had addressed the question of exactly under what conditions pensions are being resorted to and, centrally, are they serving as a way for Greeks facing the prospect of long-term unemployment to access support otherwise unavailable to them. Searching the article reveals only two references to "unemploy*" and those are both related to a specific fund, not to the rationale for turning to a pension. Especially in a severely depressed economy "early retirement" may not be voluntary and a pension may be the only alternative to death.

-

Posted by:

I have issues with the penultimate paragraph, and it's ideological basis. While I wouldn't disagree that Greek pensions need an overhaul, it is here that the ideological biases of those writing the article are laid clear.

State pensions were always designed as a communal approach to providing for the non-working elderly -- and so that they didn't fall into poverty.

The 'ownership' approach dissolves the collective/society of responsibility for what happens to the elderly. While I don't deny that it is a good thing to invest time and interest in one's retirement, the idea of 'ownership' inherently favors the wealthy who have the means and ability, though often not the knowledge, to manage their retirement assets -- note I'm not saying that they know how to plan for retirement, but can afford to pay people to do that, and can afford the fees involved. The poorer generally can not.

The idea of 'ownership' of state pensions is fundamentally diametrical to what they were founded on -- that society was going to collectively providing for the elderly. The fact that many of these pensions already fall under the poverty line, only highlights the fact that these state pensions don't provide, to quote the author's, 'a respectable level of income...'. Yet we're supposed to believe that if these same people took 'ownership' would have a respectable level of income? Where's the evidence? And what are the author's going to suggest they invest in? Clearly not the Greek stockmarket.-

Posted by:

The social contract does not require that citizens save so that when they are older they can still eat sleep and stay healthy. However when the government screws up everybody has to suffer equally until it gets fixed. The impression in the west is that only the lower classes are suffering and the Greek establishment is using this as a lever to force concessions so that the upper classes will not suffers. The Greek establishment is using its own citizens in order to blackmail the EU.

-

-

Posted by:

Thanks to Macropolis for the collection of good solid information from multiple sources and for data compilation in a format that every economic analyst will appreciate. The comprehensive analysis should be useful to those seeking to chart a way forward toward a more sustainable pension system.

Podcast - Whose property? Greece’s housing challenges

Podcast - Whose property? Greece’s housing challenges Can the Green Transition be just?

Can the Green Transition be just? Where is Greek growth coming from?

Where is Greek growth coming from? Bravo, Bank of Greece

Bravo, Bank of Greece