-

Is the Greek green transition running out of power?

Is the Greek green transition running out of power?

-

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

-

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

-

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

-

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

-

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

The IMF crisis and how to solve it

![Photo via IMF photostream on Flickr [https://www.flickr.com/photos/imfphoto/] Photo via IMF photostream on Flickr [https://www.flickr.com/photos/imfphoto/]](resources/toolip/img-thumb/2014/08/11/imf_439_1108-large.jpg)

The IMF is approaching its 70th birthday and the Greek programme has been a candidate for one of the most credibility-sapping in its history. Here I trace the IMF’s role in programme from its stormy launch; its misfiring implementation; the Fund’s half-hearted apology; and ongoing efforts to draw lessons and revise its sovereign debt restructuring framework, which appear destined to deliver insufficient meaningful change. A transparency revolution is both necessary and feasible. It worked for central banks in the 1990s. Why not the Fund?

Europe experienced twin crises, one in economy and the other in policymaking; the IMF shares responsibility for both. Its surveillance did not anticipate the crisis and its programmes did not contain it; layers of mistakes that culminated in some astonishing forecasting errors.

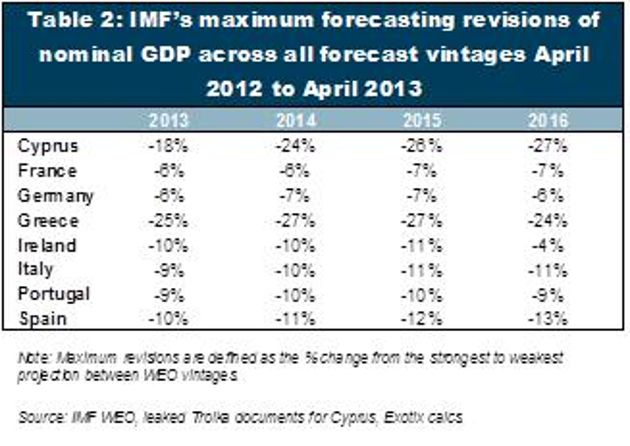

The Fund revised down its projections for the level of 2014 Greek GDP a mind-boggling 22% in just 18 months (yes, over 1 percent a month).

Greece has endured the largest but by no means the only forecast errors; errors which can be explained by the dismal algebra of exit fears +credit crunch + austerity = output collapse.

With such errors, it was impossible to produce the medium-term budgeting adjustment central to stabilising Greece.

Where did it all go wrong for the Fund?

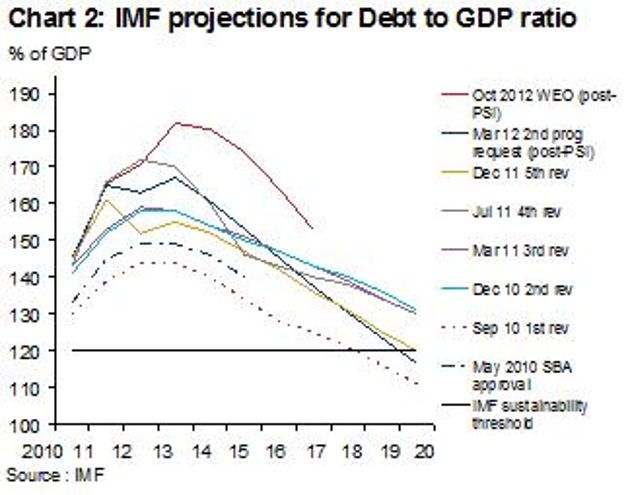

First, the Fund broke one of its most essential rules by supporting a programme in Greece from May 2010 which was inadequate to secure debt sustainability. To break the rule is to throw good money after bad; it not only delays the inevitable, but makes it worse.

Even by their own arbitrary definitions of debt sustainability (120% of GDP by 2020), the Greek programme was unsustainable between the second review (December 2010) until the fifth review (December 2011), which incorporated PSI.

Ultimately the IMF’s Greek procrastination was fruitless: Private lenders to Greece suffered a scalping, Greece did not have a bank that lent between mid-2011 and mid-2013, youth unemployment reached 60%, and the ECB had to intervene massively to keep swathes of the European banking system afloat.

Second, the IMF treated the Eurozone as a partner to be accommodated wherever possible, not as a patient to be cured. The IMF enforced voluminous but asymmetric conditionality, pertaining only to the crisis countries and never to the broken central institutions.

Third, Fund actions were hampered throughout the euro-crisis by fundamental diagnostic errors. For example:

-

Efforts to encourage bank-recapitalisation in the Eurozone were too timid and too late;

-

The Fund has consistently and unequivocally praised German supply-side reforms, even though – absent matching reforms elsewhere – they are a key cause of the euro-imbalances.

Regrets, IMF have a few

In mid-2013 the IMF published an historic staff report that raised concerns about the quality of the Fund's work on the Greek bailouts.

But then again...

The IMF’s rejection of its own staff’s mild criticism is arguably the bigger and yet under-told part of the story. The official IMF response to the staff report was contained in a single paragraph offered by its Executive Board on June 5:

Directors ... agreed that [the report] provides a good basis for all parties to draw valuable lessons ... noted ... overly optimistic assumptions, including about growth ... [and] noted the benefits of a timely restructuring of sovereign debt….

Is that it? To those of us familiar with IMF Board-speak, it sounded as though the report may had just been binned. It said nothing about what the "valuable lessons" were; or about follow-up work on how to learn from them. And who could be against "timely" anything?);

The prevailing mood in IMF management was one of "je ne regrette rien".

The IMF’s policy response so far

In April 2013, the IMF published its first major paper in a decade on sovereign debt restructuring. But its review got off to a false start.

The IMF’s initial proposal aimed to enhance the crisis resolution toolkit, partly by incentivising more timely restructurings, in turn by making them less of a big deal.

In short, if the IMF determines that debt is in an uncertain “grey” area of sustainability the Fund would lend. But in order not to “waste” official money bailing out private creditors, the sovereign would have to bail in the latter by “reprofiling” debt: extending maturities on all private sector bonds and loans falling due within the life of the programme.

But the rating agencies would spell “reprofiling” D-E-F-A-U-L-T, and I doubt there will ever be a default without serious consequences.

The centrepiece of the proposals – to virtually automatically link Fund lending to a partial creditor-bail in – was a radical, misguided departure from the case-by-case approach, the decades-old first key principle underpinning the approach to sovereign debt restructurings.

The Fund published a revised paper on Sovereign Debt proposals in June 2014 responded to many of the criticisms but will probably not add much to the sovereign debt restructuring tool kit. If reprofiling was so obviously good, why has it not been used more in past crises?

The main problem is not with the toolkit, but with the Fund itself.

What needs to change?

The IMF barely needs to provide any justification of some absolutely crucial analytical and policy decisions.

There are numerous other examples of inadequate explanations, including: (1) the decisions to go ahead with the Greek programme in 2010 and deny the possibility of restructuring; (2) implicitly supporting the view that the Greek debt buyback would make debt sustainable when it mainly entailed shuffling debt between the state and state-owned banks.

At a conference in 2013, the Fund was asked to defend its support of measures to seize 10 per cent of all Cypriot bank deposits, a decision that came close to reigniting the euro crisis, until it was shamefacedly withdrawn. The IMF refused to answer.

The IMF Board

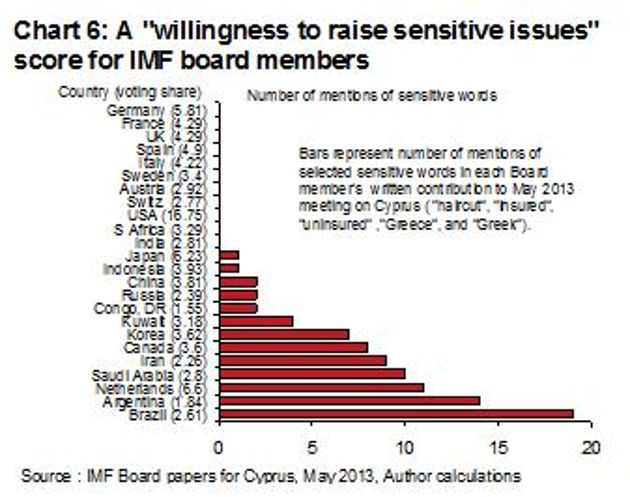

Any assessment of IMF has to include its Board, the place where staff analytics and international politics meet and mould policies, sometimes with poor results.

The politicisation of the Board is stark in matters concerning Europe. The sum of votes of seats where a western European country is the biggest shareholder is nearly 40% of total Board votes, forming a bloc that directly led to the lack of anticipation or coherent response to the Eurocrisis.

The leaked Cyprus Board discussion provides a rare insight into how the Board actually works. Directors should have sought explanations regarding the IMF’s public flip-flop between taxes on all depositors versus haircuts solely on uninsured deposits, or the program’s insistence that no depositors in Greek branches of Cypriot banks be haircut, pushing even more of the burden on Cyprus.

A word-count experiment is revealing. None of the statements written by any European Director (other than Cyprus’s representative), or the United States, contained the words “haircut”, “insured”, “uninsured” or “Greece”, symptoms of the most sensitive issues.

The Board should:

-

Include appointments akin to "non-executive directors" – who do not represent countries at all

-

Publish detailed minutes, promptly, including all Directors' objections to decisions,

-

Record individual voting and each Director's individual rationale in all the big programmes.

Transparency revolution

Most of the IMF’s failings derive from shortcomings in institutional design and the best way for the Fund to restore its credibility that institutional biases are being tackled is to open up its kitchen to public scrutiny.

Fund staff and real time checks and balances

The silence of the technocrats responsible for global consistency of IMF advice is a sign that politicisation runs too deep.

By the time the average Greek programme document has been circulated around the various constituencies of the IMF Board members, 100s would have provided comments. To misquote Churchill, "Never in the field of institutional accountability has so little been achieved by so many, for so many."

IMF Policy Committee

To overcome this bureaucratic quagmire of review and consequent obfuscation of accountability, an IMF Policy Committee should be formed.

The committee should be centred on the Managing Directors, but should provide a role for other key members of staff whose existing role is to provide checks and balances, and (like MPCs) should include external members with no role IMF management structure

It should publish minutes and votes of key recommendations made to the Executive Board. There needs to be individual accountability.

Post-event evaluation and IEO

The IEO is an internal auditing office that offers the potential for effective lesson-drawing and a medium-term deterrent to IMF mishandling.

The IEO’s work programme, as outlined in the Fund’s 2012 Annual Report, reads like an instruction to stay away from the elephant in the room; there is no clue of the Fund’s role in the euro crisis.

It is banned from evaluating any active programme! This should change immediately.

The Managing Director

The Head of the Fund should be selected by a transparent open process, where the most qualified candidate gets the job. At best, it is just plain silly that every MD has originated from Western Europe for the last 67 years. Why is that not racist?.

Arguably, the Fund was led by three "inappropriates" in the 2000s. Each of Kohler, De Rato, and DSK has suffered some degree of tarnished reputation since their appointments. Yet they were able to varying degrees cast the Fund in their image.

Conclusions

Inflation targeting regimes were set up when monetary policy credibility was at a low ebb; a strong analogy with the Fund.

Now is the perfect time for the Fund to open up its kitchen and show the world the ingredients that go into forming key decisions. Many central banks turned an endowment of low credibility to an advantage from the 1990s by introducing radical reforms in transparency and accountability.

Without a transparency revolution at the IMF, I see little prospect that will perform better in the run-up to or the management of the next global crisis.

*Gabriel Sterne is the head of global macro investor relations at Oxford Economics. You can follow him at: @GabrielSterne. The full version of his research briefing is available here.