-

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

-

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

-

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

-

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

-

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

-

15% Uncertainty: Greece, Europe and the tariff shockwave

15% Uncertainty: Greece, Europe and the tariff shockwave

When will Greek banks operate as credit institutions again?

Despite the successful recapitalisation process and continued restructuring of the Greek banking sector, the credit transmission mechanism towards the real economy remains severely impaired. Two key reasons account for this severe deficit.

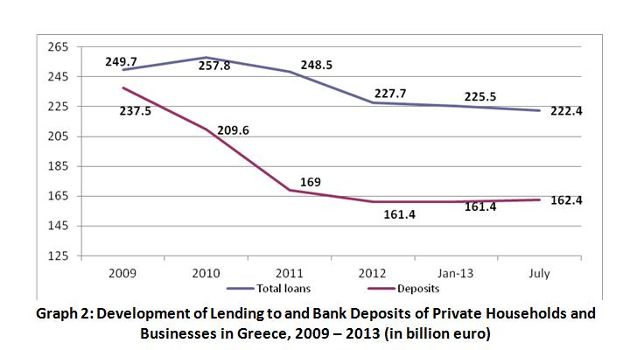

Firstly, the depositor outflow of the past years has not been reversed to a degree that would improve the liquidity position of Greek banks and hence their lending capacity.

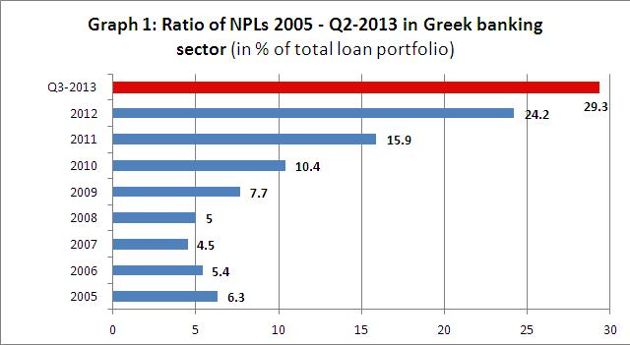

Secondly, the multi-year economic contraction has severely impacted on citizens’ capacity to meet their repayment obligations on mortgages, credit cards and corporate credit. Greek banks are therefore sitting on an ever-rising share of non-performing loans (NPLs), which badly affect their lending capacity.

Both factors contribute to impair balance sheets and are the main reason why a lending recovery has yet to materialize itself in the Greek real economy.

Source: Own calculations and Bank of Greece yearly data.

Credit contraction to private households and businesses is happening at an uninterrupted pace for more than two years now. Put otherwise, since the beginning of 2011 Greek banks have not been in a position to adhere to their core function, namely to provide affordable credit to the demand side, in particular those small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that take up over 90 per cent of the Greek corporate landscape.

Significant balance sheet risks because of NPL formation and low liquidity levels continue to challenge the operational capacity of Greek banks after the recapitalisation. In addition, the capital stock of the Greek real economy remains too thin and far too dependent on bank dominated lending capacity. Any attempt of the Greek real economy to regain its footing and identify new growth paths can only have a realistic chance of succeeding if and when Greek banks become part of the endeavour.

Source: Kathimerini, August 29, 2013, economic section, page 3.

This partnership to sustain what some observers have started to call Greekcovery has yet to be operational and yield results that signal a turnaround. We must rather voice concern over the possibility that domestic lenders will first and foremost concentrate their lending activities on established [large] corporate customers and thus favour those businesses which after five uninterrupted years of recession are still in the position to provide sufficient collateral for the credit facilities they require.

In such an admittedly dire outlook the remaining constituency of potential customers will be fighting amongst themselves to gain access to loan tranches that are too little too late and are advanced under conditionality requirements that will prove difficult, if not impossible, to finance.

Credit crunch and disconnecting from financial services

The severity of credit constraints in Greece’s real economy is further illustrated by two structural problems that increasingly reflect the dire conditions under which private households and businesses try to keep their heads above water.

On the one hand the Greek government has been successful through a multi-year austerity course to bring down wages and salaries in the public sector. This process of wage contraction has been supplemented by private sector redundancies and an unprecedented number of new sectoral and firm-level bargaining agreements, which have sought to reduce labor costs in the real economy during the past three years. According to the Central Bank of Greece unit labor costs have declined by more than 27 per cent between 2010 and Q3-2013.[1]

But this apparent success story risks being undermined by a development in the opposite direction that constrains the recovery attempts. The high costs of capital for businesses constitute the most significant obstacle to affordable and timely lending facilities. The central problem of the real economy in Greece is today not anymore the high [unit] labor costs. Rather, the key impediment is the elevated credit costs for capital and thus the lack of liquidity injections transmitted through Greek banks. In particular towards SMEs, the availability of credit and affordable borrowing rates are handled in a very restrictive manner by domestic lenders.

But it is not only the exorbitantly high interest rates for funding that serves like a millstone around SMEs’ necks. Greek banks have also increasingly changed course and now attach unprecedented levels of collateral conditionality onto credit arrangements of the demand side.

Let us illustrate the issue that is at heart of the matter with a comparative example. A German mid-sized company, export-oriented to southeast Europe, including Greece, which is seeking a loan of 1 million euros from its local bank branch in Frankfurt with a maturity of five years will currently have to pay an interest rate between 3 and 4 percent. This level is a record low for corporates in Germany, in the post-unification era!

By contrast, a Greek medium-sized company with the same corporate profile, i.e. export-oriented (including to Germany) and a good order book, sound credit history despite all the challenges of the past years, would currently have to pay for the same credit line an interest rate ranging between 6.3 and 9.5 percent in Athens due to Greek banks’ counter-party risk. Contrary to the record lows available in Germany, the inflation-adjusted borrowing costs in Greece have now hit an average of 6.6 percent. This is the highest level since the country joined the euro area!

Under such a combination of adverse credit conditions and severe liquidity deficits to invest in Greece, a growing number of well-known domestic companies are either being forced to close shop in their homeland or vote with their feet, seeking better credit pastures abroad. In the past 12 months alone, four blue chip companies listed on the Athens Stock Exchange have either completely left Greece or relocated their administrative headquarters abroad.

Apart from Coca-Cola HBC, S&B Minerals and Fage, Greece’s largest metals manufacturing company Viohalco surprised analysts and observers in September 2013 with the announcement that it would transfer its headquarters to Belgium. The issues of corporate taxation and labour costs played no part in Viohalco’s relocation decision. The decisive factor, rather, was the expectation of the company’s owners to attain better access to funding options through foreign banks.

At a time when the government of Prime Minister Antonis Samaras is emphatically trying to lure foreign investors to Greece, the opposite trend is emerging in his homeland: domestic companies are leaving behind them the frustrating experience of wanting to invest in their home markets and being held back by domestic lenders who attach far too arduous strings to credit facilities. This movement away from Greece is anything but a vote of confidence by these corporate entities in the economic sustainability of the country and could not come at a less opportune moment.[2]

The second structural problem concerns the demand side of the credit transmission chain. In recession-hit Greece, more and more private households and businesses have lost their capacity to apply for loans. More specifically, because they either cannot meet the monthly mortgage obligations anymore, or a cheque they issued bounced for lack of funds in their accounts, or they are numerous months behind in their credit card payments; any one or a combination of these reasons risks landing them on an index of defaulting debtors, the so-called Tiresia index. Any registration on this index has dire consequences for the individual party concerned. Such potential costumersrisk seeing the barriers to the doors of local bank branches rising, with the repercussion that they are disconnected from key financial services.

Among those affected are numerous sustainable companies and creative start ups that had weathered the economic storms of the past years. They operated their business under adverse conditions and considerable personal risk, frequently using remaining financial resources from their families and despite credit lines being refused by their local banks. Many of these companies are from the SME sector and comprise a diverse mix of economic activities.

What they need first and foremost today is the provision of working capital in order to keep their business afloat and the refinancing of existing credit lines through their domestic lender. If this group of entrepreneurs are not provided in due course with sufficient liquidity then the consequences of this credit crunch are severe. Any attempt at restarting the engines of economic recovery in Greece would be delayed and precious time lost to keep such companies alive. Put otherwise, the normalisation of the credit transmission mechanism through participating domestic lenders is a matter of urgency in Greece today.

What are the preconditions the would enable such a normalisation? Greek banks would first have to focus their activities on a sustainable increase of its depositor base. Recovering the loss of more than 30 per cent of customers’ deposits during the past three years has only started, albeit at an inconsistent pace and still lacking a critical mass of inflows. The crisis in Cyprus from April 2013 where Greek banks have an extensive branch network had immediate adverse repercussions on the deposit inflow dynamics of domestic lenders.

A second cornerstone should rest with the conditionality of the aforementioned bank recapitalisation. Through framework agreements with Greece’s bank bailout fund, the HFSF, the four systemic Greek banks have committed to an extensive restructuring of their strategic priorities, downsizing branch networks (including abroad) and unprecedented transparency requirements in their day-to-day operations.

But what these framework agreements critically lack are specific lending targets to the real economy, in particular towards SMEs. This proposal does not suggest that the government, the HFSF or any other representative from the troika should be involved in making lending decisions for the banks. That would be a recipe for disaster. Additionally, the track record of government intervention in Greek banks’ operational priorities prior to eurozone membership in 2001 underlines the need for restraint.

The inclusion of lending targets as a conditionality requirement for recapitalized banks is not without precedent in the eurozone. In 2008, the French bank regulator in agreement with the European Commission included in the context of so-called behavioural commitments specific lending corridors and timetables for commercial banks that had received state-sponsored capital injections. Domestic lenders had to agree in writing that funds obtained from the French regulator SPPE would be used

· To finance the ‘real economy’;

· Maintain an annual growth rate of 3-4 per cent of overall lending to the French economy and;

· Report on a monthly basis about lending volumes.[3]

A similar method of behavioural commitments was also applied to three recapitalised banks in Portugal in 2012. The 6.6 billion euro injected in privately held Banco Comercial Português (BCP), Banco BPI and state-owned Caixa Geral de Depósitos ensured that they would be in a position to meet the requirements for core tier one capital ratios set by the European Banking Authority (EBA).

In return for this capital injection, all three institutions had to commit themselves to support economic growth through corporate lending. In the cases of BCP and BPI because of their listing on the Lisbon Stock Exchange, the lending requirements were even more specific. Each domestic lender had to invest a minimum of 30 million euro per year in the capital of small and medium-sized companies.[4]

The Portuguese example is also noteworthy for the fact that it became the first so-called programme country (i.e. under an international economic adjustment programme of the Troika) to link state-sponsored capital injections with behavioural commitments such as defined lending targets for the corporate sector. Hence, it would be rather careless to argue that Troika representatives are against such options or that the European Commission would represent a potential stumbling bloc.

Such a similar strategic approach incorporating behavioural commitments post-recapitalisation and supported by Greek banks would have an important indirect impact in the wider public debate in Greece. The inclusion of lending targets into such framework agreements could contribute to correcting a formidable image problem that exists between the supply and demand sides of the credit transmission mechanism today. Repairing this fraught relationship and reducing the reputational costs of this image problem is in the best self-interest of Greek banks.

The criticisms frequently heard from citizens - the feeling on Main Street in Athens, if you will - about recapitalisation is that in addition to not lending enough bank executives in the four systemic financial institutions now benefit from a completely different, highly concentrated banking sector with large domestic lenders and a remaining niche of small entities.

The unprecedented consolidation and concentration process in the Greek banking sector has created resentment among those financial institutions left behind without HFSF-sponsored capital injections. Moreover, the developments have reinforced the notion that once a financial institution has acquired a critical mass in terms of size of assets and liabilities it becomes proverbially ‘too big to fail but small enough to bail’.

Nowhere was this perception more clearly illustrated than in the case of Piraeus Bank. Through mergers and acquisitions during the course of the past 18 months it became the second-largest bank in Greece in terms of total assets (after National Bank of Greece) and the single largest in terms of its extensive branch network, home and abroad. While it ranked in fourth place in 2011 (regarding both indicators) Piraeus Bank executives understood faster than any of its peers that size matters and would constitute a critical diagnostic tool prior to recapitalisation decisions being taken about individual lenders by the HFSF.[5]

*Jens Bastian is an independent economic and investment analyst for southeast Europe. From 2011 to 2013 he was a member of the European Commission Task Force for Greece in Athens. Bastian has worked in the private banking sector in Greece and has held various academic positions at Nuffield College and St Antony’s College in Oxford as well as The London School of Economics in London, UK

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[1] See Bank of Greece, Note on the Greek Economy, Athens, 11th October 2013.

[2] The Greek clothing retailer Sprider suspended its commercial operations at its outlets in October 2013. After more than 35 years in the Greek market the subsidiary of the Hatzioannou Group tellingly cited “the intransigent stance of banks and their refusal to continue existing funding lines” as the main reason for the shutdown of the retail outlets. 887 people lost their jobs as a consequence of the shutdown.

[3] For the French case see the European Commission, 8th December 2008, State aid N 613/2008 – Republic of France, Capital-injection scheme for banks, p. 9, Brussels. More generally Commission Communication from 22 July 2009 that seeks to clarify compliance requirements of bank recapitalisation procedures in member states with existing state aid rules: http://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/legislation/restructuring_paper_en.pdf.

[4] See Financial Times, June 4th 2012, ‘Lisbon to inject €6.6bn into largest banks’.

[5] In the course of 2012-13 Piraeus Bank acquired the following institutions: Agricultural Bank of Greece, Geniki Bank from the French banking group Société Générale, the Cypriot bank units operating in Greece and Millenium Bank from Portugal’s BCP Millenium. Piraeus Bank today has 25.000 employees, 1.750 branches and the Group’s combined total assets amounted to 99 billion euro in Q1-2013.

2 Comment(s)

-

Posted by:

If the government has indeed agreed now to shut down Greek bank branches abroad (as requested by Troika in September), then we can only conclude that Troika is not impartial and is abusing its power to aid other countries commercial interests.

Most Greek branches are in the Balkans and are profitable. There is no commercial sense in shutting them down. But it does give a tremendous boost to Austrian banks, who are their main rivals in the region. -

Posted by:

> When will Greek banks operate as credit institutions again?

The presentation of economic numbers is interesting, but does not answer the question. Imho banks have several valid reasons to remain very careful with new business credits in Greece.

a) The political and social instability results in a high additional risk for all sizes of enterprises which shows up in higher interest rates for existing credit lines and very restrictive granting of new credits.

b) There is additional uncertainness in the legal system, taxation etc.

c) With the high number of nonperforming credits banks do not want to have more of the same risks.

For the same reasons a&b foreign investors are reluctant to invest in Greece and some prudent companies have preferred to dislocate their headquarters abroad.