-

15% Uncertainty: Greece, Europe and the tariff shockwave

15% Uncertainty: Greece, Europe and the tariff shockwave

-

Summit of transactions – Erdogan and Trump

Summit of transactions – Erdogan and Trump

-

Podcast - DETH and taxes: The only things certain in Greek politics

Podcast - DETH and taxes: The only things certain in Greek politics

-

How will Trump's tariffs affect Greece?

How will Trump's tariffs affect Greece?

-

Podcast - Subsidise this: Fraud scandal delivers new blow to Greek PM

Podcast - Subsidise this: Fraud scandal delivers new blow to Greek PM

-

Fet-a-ccompli: Tariffs and Greece’s big cheese

Fet-a-ccompli: Tariffs and Greece’s big cheese

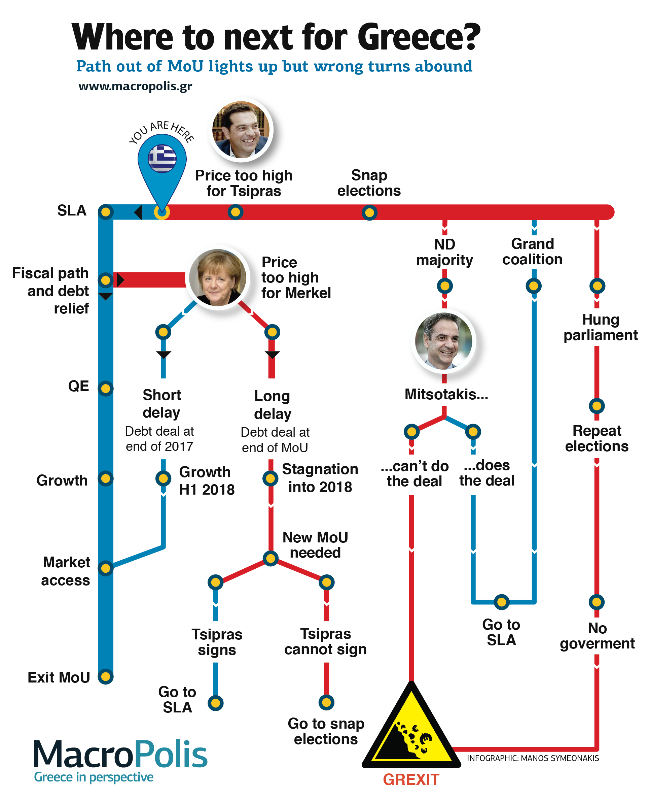

From MoU exit to Grexit: Where next for Greece?

In September last year, when Alexis Tsipras visited New York to speak at the UN Assembly, he held a meeting with some heavyweights of the international investment community.

The Greek prime minister was reportedly advised by the participants that if he wanted to build trust in Greece as an attractive investment destination, he should shift focus from his main objective of debt relief towards ensuring Greece’s participation in the European Central Bank's quantitative easing (QE) programme. The investors apparently pointed out to the SYRIZA leader that such a development would have a wide range of benefits for Greece and provide the steadiest path towards regaining market access and the successful completion of the current programme, without the need to follow it up with a fourth memorandum of understanding (MoU).

Tsipras seemingly heeded the advice and, just as the second review was about to start, he charted a path out of the crisis. He set out his intention to close the review by December 2016, secure QE at the start of 2017 and dip his toe back into the markets with a small issue or two early this summer when Greece has to roll over the bond that it issued in 2014, when Antonis Samaras was prime minister.

However, the timetable Tsipras identified last autumn has gone up in smoke. What seemed like a rather straightforward review, which lacked significant interventions on the fiscal side but would require some concessions on labour reforms, turned into a political conundrum for Tsipras. An attempt to reach an all-round deal at the December 5 Eurogroup foundered. From the end of January, it became apparent that – in the absence of any concessions from Greece’s lenders on fiscal targets beyond 2018 – securing the International Monetary Fund’s participation would require the Greek government to pre-legislate another 2 percent of GDP in tax hikes and pension cuts.

Since then, there has been much back-and-forth between the government and the institutions, with minimal tangible outcome. The talks have moved from Athens, to teleconference and, over the last few days, Brussels, with the aim of establishing enough common ground for the second review to be concluded. The measures being demanded by the lenders are painful for Tsipras, his party and many Greeks but the potential rewards are great as well.

The best-case scenario

If Tsipras’s administration is able to reach a staff-level agreement (SLA) with the institutions, this would pave the way for a commitment by the eurozone for medium-term debt relief and a deal on Greece’s fiscal path, which would consist of primary surplus targets that would be lower than the 3.5 percent of GDP originally envisioned and for less than the 10 years agreed in the fraught summer of 2015.

Armed with these gains, the coalition could then oversee the return of growth to the Greek economy as well as access to the European Central Bank’s quantitative easing programme. In turn, this would create more favourable conditions by pushing Greek sovereign yields down to around 5 percent, which would enable a small, medium-term issue as part of a modest return to the international bond markets. If Greece can refinance its debt on the markets, the chances of needing a fourth bailout programme diminish and Tsipras can lead the country out of its so-called “memorandum era”.

This would be a significant moment for Greece and its people, but also a much more positive legacy for Tsipras and SYRIZA to take with them than the last couple of years in power.

However, there are two main ways in which this path could be altered, forcing Greece to take a different route.

Tsipras can’t sign

The first is the possibility that Tsipras will decide that what the lenders are asking from him, including 2 percent of GDP in new fiscal measures and further liberalisation of the energy and labour markets with very little in terms of counter-measures that will make a tangible difference to taxpayers, are unacceptable or will not be approved by SYRIZA’s central committee and MPs.

This would lead to snap elections, which New Democracy is highly likely to win. The question is whether the conservatives would have enough votes for an outright majority.

If they win and gain more than 150 seats in the Greek Parliament, Kyriakos Mitsotakis’s party will be able to agree to the lenders’ terms and clinch an SLA, allowing him to be the prime minister that oversees Greece’s progression through the virtuous stops along the way to an exit from the programme. The same could apply if New Democracy wins but does not gain an outright majority, forcing it to work with other opposition parties, such as PASOK and Potami (should they make it into Parliament) to form a coalition.

There are two ways in which there could be a dramatically bad turn. One is if a New Democracy government is unable to reach an agreement with the lenders. Mitsotakis has insisted that he will negotiate better terms, which seems a highly optimistic claim given the fate of previous opposition leaders in Greece who claimed exactly the same thing. Also, SYRIZA in opposition following snap elections would very likely be a reincarnation of its older, more militant, self, perhaps creating an environment of extreme political and social tension. After all, despite suffering brickbats for signing the third MoU, Tsipras could argue to his followers that he drew the line somewhere.

The other danger is if the snap elections are inconclusive and repeat polls are held using the proportional representation system (as per the overhaul of the electoral law approved by Parliament last year), this would lead to political paralysis. In either of these situations, the possibility of Greece defaulting on its July debt obligations and crashing out of the eurozone would be high.

Merkel can’t sign

The other potential stumbling block is Germany, which may be reluctant to agree to the kind of debt relief that the IMF is demanding to return to the Greek programme.

If an SLA is agreed, the next step will be for the Greek Parliament to vote the necessary measures. After that, the IMF and the eurozone would have to settle the issue of debt relief and the fiscal path that Greece has to follow for the coming years.

If German Chancellor Angela Merkel decides to wait until after her country’s federal elections in September to agree to any debt relief package, this will likely dent Greek growth hopes in 2017, leading to 2018 being the real year of recovery. At that point, in the absence of any political instability, Greece should be able to stay on track and regain market access, allowing it to exit the MoU when it expires in the summer of 2018.

However, if the debt agreement is put off further and Berlin refuses to agree any deal before the end of the programme, this delay will lead to the economic stagnation Greece saw in 2016 continuing in 2017 and carrying over into 2018.

This will mean that a return to the markets is not possible for Greece and, on expiry of the current programme, Tsipras will be forced to sign a fourth bailout. If he agrees, then the process for exiting the new MoU will begin all over again. If he refuses, then snap elections will be needed and the scenarios that flow from that event will come into play.

The Greek crisis never evolved in a linear way, since the situation was so fragile that even minor shocks threw it off track and decisions within and outside of Greece shook up the country.

Decision-makers have in front of them a path that can lead Greece out of the miserable state it has been in for the best part of a decade. The stops along the way are not easy to reach for anyone but the prospect of a wrong turn carries considerable peril. For now, we have to wait and see where next for Greece.