-

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

-

15% Uncertainty: Greece, Europe and the tariff shockwave

15% Uncertainty: Greece, Europe and the tariff shockwave

-

Summit of transactions – Erdogan and Trump

Summit of transactions – Erdogan and Trump

-

Podcast - DETH and taxes: The only things certain in Greek politics

Podcast - DETH and taxes: The only things certain in Greek politics

-

How will Trump's tariffs affect Greece?

How will Trump's tariffs affect Greece?

-

Podcast - Subsidise this: Fraud scandal delivers new blow to Greek PM

Podcast - Subsidise this: Fraud scandal delivers new blow to Greek PM

In the case of Greek debt, it's the "how" that's missing

Over the period of nine months that it took to complete the second programme review, the role of the International Monetary Fund as Alexis Tsipras’s strongest ally to secure debt relief was one of the many curved balls that flew past the Greek prime minister.

Working under the assumption that German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schaeuble would have to concede on the issue of debt relief because he needed the IMF on board to even secure a disbursement to Greece before its July debt maturities and given the very vocal stance of the Fund on the need to deliver serious interventions on Greece’s debt, there was an impression in Athens that this time debt relief would not be kicked further down the road.

Schaeuble’s determination to avoid the issue and - as IMF managing director Christine Lagarde described following the June 15 Eurogroup - the fact that time was pressing and nobody wanted Greece to encounter a funding crisis, facing a default on the ECB, led the Fund to dust off a legacy process that allowed things to move on. At the same time, it would not commit the Washington-based organization to anything that it would be uncomfortable with, while still leaving the debt issue open for further discussion before it needs to contribute any funding.

In a regular briefing on Thursday, the IMF spokesman Gerry Rice reminded that there is considerable distance between the Fund and the Europeans. He added that when the topic of debt is revisited, considerable concessions will be required if the two sides are to bridge their views on the framework, the assumptions, the fiscal projections and what interventions will be needed to bring Greece’s annual debt servicing costs within a set threshold of 15-20 percent of GDP.

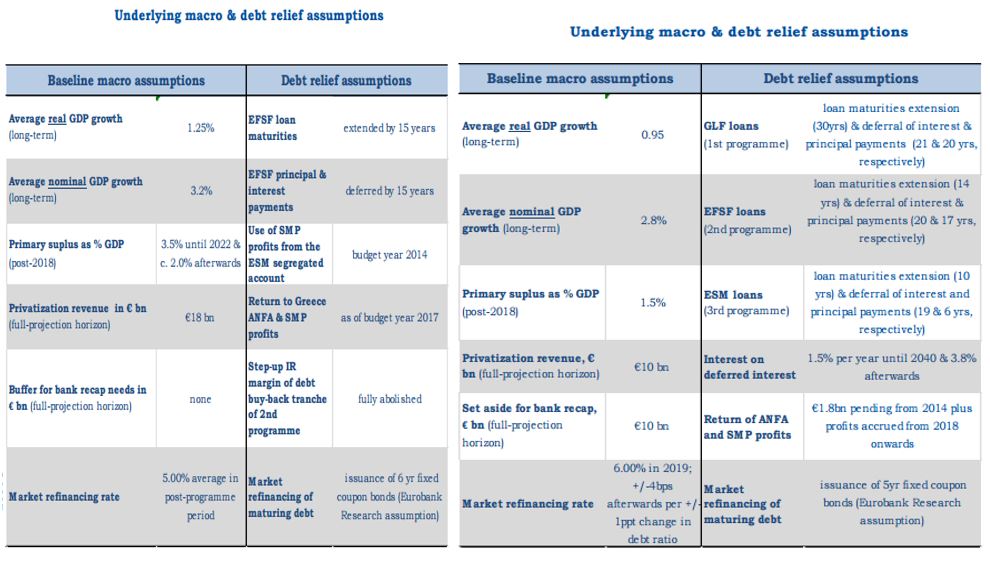

Recent research by Eurobank sets out the distance that needs to be covered.

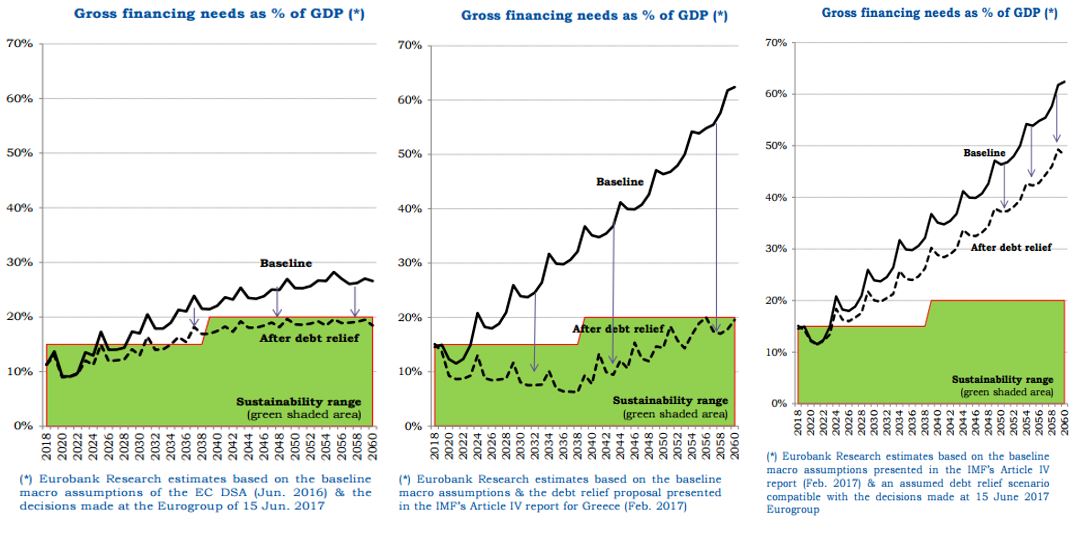

Mainly, the gap in projections for Greece’s long-term growth potential and differing views on the ability of Greece to maintain high primary surpluses for decades, along with the IMF’s views that some funds need to be set aside for potential bank support, lead to baseline scenarios that diverge immediately and lead to a gap in gross financing needs that exceeds 30 percentage points by 2060.

Naturally, the eurozone believes that within the framework agreed in Luxembourg a couple of weeks ago, Greece’s financing needs will fall within the required parameters.

The IMF believes that this threshold can only be achieved when all loans to Greece are extended by decades. The same goes for interest payment deferrals. The eurozone is only considering extending the maturities and the interest payments of the EFSF loans of the second programme.

Based on what is on the table after the June 15 Eurogroup deal, Eurobank estimates that the Fund’s assumptions move only marginally and Greece is nowhere near the 15 percent and 20 percent thresholds of gross financing needs, the gap is in the volume of 10 percentage points in 2040 and approaching 30 percentage points in 2060.

There seems to be a general consensus that Greece needs to be helped to get back on its feet, but there is also a huge task ahead to forge an agreement on how this could happen.

*You can follow Yiannis on Twitter: @YiannisMouzakis

2 Comment(s)

-

Posted by:

I think it's the wrong approach trying to second guess what Tsipras' tactics did or didn't do.

The bottom line is that against impossible odds this government succeeded in lowering financing costs beyond what the previous failed Samaras government was able to achieve and the proof is in the pudding:

https://www.bloomberg.com/quote/GGGB10YR:IND

Greek companies like the Mytileneos Group are now able to raise financing at 3.1%.

Bottom line: Despite the impotent EU politics somehow, someway the "amateur" Tsipras keeps hitting balls out of the park and that's something that now his political opponents are watching with awe. -

Posted by:

"...what interventions will be needed to bring Greece’s annual debt servicing costs within a set threshold of 15-20 percent of GDP". I presume that this is the combination of debt service (interest) and debt refinancing (principal). No one in his right mind can expect Greece, of all countries!, to reduce its debt in nominal terms, so debt refinancing is a given in any scenario. The real question is how much of its general revenues the state will have to allocate to interest.