-

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

-

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

-

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

-

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

-

15% Uncertainty: Greece, Europe and the tariff shockwave

15% Uncertainty: Greece, Europe and the tariff shockwave

-

Summit of transactions – Erdogan and Trump

Summit of transactions – Erdogan and Trump

The euro debate Greece is not having

You may be amongst those who are not convinced of the devastating effect that the policy mix and pace of fiscal contraction in Greece is having on society. If so, you may subscribe to the official line trotted out by the country’s lenders that the program is helping the country regain competitiveness and the economy fix its external imbalances. This is the greater cause that is demanding such a sacrifice. There is no gain without pain, goes the argument.

However, more than three years into the troika program there is very little evidence that one of these key objectives has actually been achieved. It is extremely doubtful whether the Greek economy is indeed regaining part of the competitiveness it lost after joining the euro.

There is no dispute that Greece's current account, from a staggering deficit of close to 35 billion euros in 2008, is nearing balance. But the majority of the correction of the trade deficit is covered by a collapse in imports due to domestic demand almost evaporating after three years of austerity and disposable incomes plummeting by almost a third.

It is a fact that Greek exports are on the rise and that 2013 will be a record year for tourism but Greece's total exports will still fall short of the 56-billion-euro level they reached in 2008, a time when the country was uncompetitive, if you believe the prevailing argument.

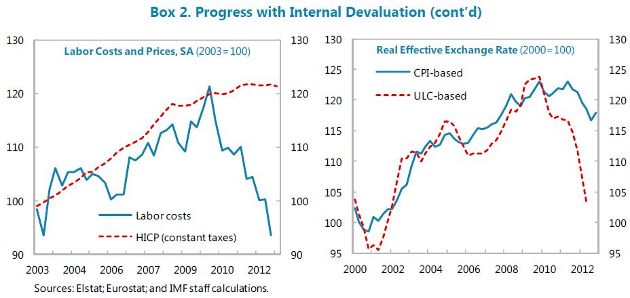

In a June document evaluating its involvement in the Greek program back in May 2010, the IMF includes the chart below, which shows that although labour costs have nosedived since 2010, prices - which really reflect how competitive you are - have hardly moved to cover the lost competitiveness.

There is much to be debated about the prices’ resistance to falling at the same pace as wages, and it is often one of the troika's arguments that there is not enough competition in the products markets. However, aside from the fact that prices are known to be sticky downwards, in a cash-starved economy that is in a downward spiral it may even be a prudent management decision to keep prices up, despite falling wages. This helps compensate for shrinking revenues and profits.

The “internal devaluation” rationale is that, in the absence of the currency devaluation which automatically makes everything produced domestically cheaper to the outside world, you suppress domestic demand with the aim of reducing imports and correcting the trade balance. You also implement cuts in costs which are variable, such as wages, unlike other input factors that further feed the effort to push down domestic demand. This naturally leads to higher unemployment and more people without disposable income further suppressing domestic demand. This places the wage negotiating advantage on the employers’ side due to the oversupply of labour pushing wages downward either via new collective agreements or wage negotiations at the enterprise level.

Overall, it creates a perfect feedback loop and a concerted effort to sink an economy.

You might think all this is worth it if there is light at the end of tunnel but that is not true in Greece's case. After three years of brutal austerity policies, Greece remains in a heavily overpriced currency for its economic standards.

A research paper by Morgan Stanley published in September puts the fair value of the euro against the dollar for the Greek economy at just over 1 dollar. The same figure for Germany is 1.53 - the currency currently trades against the dollar at 1.35. The difference between Greece and Germany is about 43 percent and Greece needs the euro to be 25 percent cheaper than its current levels to have a fair chance of being competitive.

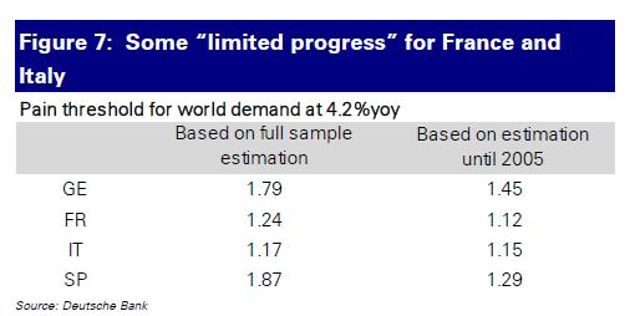

A paper by Deutsche Bank (DB) on foreign exchange pain thresholds puts Germany's at 1.79 against the dollar. Simply put, Germany is in a situation where the euro has to appreciate from its current levels by circa 33 percent before it starts feeling any strain on its competitiveness while Greece is already in this position with the euro at its current trading levels.

This is the definition of imbalance. Most worryingly, three years of policies that led to a quarter of the Greek economy vanishing does not seem to have made much of a dent on this indisputable fact.

It recently became evident that Germany has no intention of covering even part of this gap as it sees its economy benefiting from the deeply depreciated - for German macroeconomic standards – euro. So, all the adjustment will need to come from Greece and other peripheral countries. In the same DB paper the pain threshold for Italy and France is just 1.17 and 1.24 respectively, which puts even the second- and third-largest economies of the eurozone in an awkward place on the competitiveness front.

It is a debate on these plain macro facts that is missing in Greece. Any discussion around the currency has been stigmatized and leads to political labelling. The real question we need to answer is how much of the economy and society are we willing to sacrifice to stay in the euro. And if Greece’s conscious decision as a nation is to remain in the euro, is there an actual national plan or we will find ourselves in a perpetual deflationary vicious cycle of low wages, subdued demand and high unemployment because we will remain a services economy with low value added and labour intensive industries?

Questioning the benefits of a currency whose flaws and institutional weaknesses have been so blatantly exposed over the last three years should not earn one a place in the 'drachma lobby'. These questions should be used as the fulcrum for a much needed debate on how Greece will be able to respond to the euro challenges. It is about time we have a debate that extends our horizon beyond the next troika review and loan tranche, above accounting primary surpluses and superficial success stories.

So far, neither the government, nor the opposition are making any contribution towards these pressing issues. If this does not change, Greece’s task ahead will remain Sisyphean.

7 Comment(s)

-

Posted by:

Which country is 'NET'? Should that be 'NED'=Netherlands?

These numbers are clearly important. But as non-expert it is easy to get totally confused. Why give a graph with values in terms of a 'real dollar'? What's the dollar got to do with it? Is it more intuitive to make a graph comparing the 'relative buying power' of a Euro, and also the "buying power of wages/income" in different EU countries?

I'm also very curious why this large difference in buying power of the Euro doesn't immediately vanish due to trade of goods, or a financial carry trade. Which are the mechanisms that sustain this difference? Are German wages too low and is this what is depressing prices? What is the effect of the different interest rates?

And which are the types of policies that can correct for the forces of imbalance? What does QE do? Would it make sense to increase VAT in Germany and lower it in Greece to move towards balance? How irresponsible is it that the German government insists proudly on its 'black zero' deficit?

It seems absurd to realise that a Greek working in Germany, sending money home, gets 'taxed' by 30% higher price levels in Greece vs Germany. It seems as absurd that somebody exporting goods from Greece would get a 43% lower price in Germany. .. the difference is even so large that these two percentages are clearly different. -

Posted by:

"The “internal devaluation” rationale is that, in the absence of the currency devaluation which automatically makes everything produced domestically cheaper to the outside world, you suppress domestic demand with the aim of reducing imports and correcting the trade balance."

--> This is simply wrong. internal price=domesticprice/importedprice or the nontradedprice/tradedprice

the aim is not to suppress domestic demand - reduced imports are just a side effect - but the aim is to reduce the price levels of domestic services and products! The artificially high margins in domestic prices (and their underlying wages, especially in the state sector) that have occured during the boom now have to drop down again so that domestic products are prefered to imported goods again.

And this is totally independent from the exchange rate! The REAL EFFECTIVE EXCHANGE RATE can be calculated for any region or even village just by looking at real domestic costs and price levels in relation to real costs and price levels of the "foreign" trading partners - which could just be the next village :)

Exchange rates are just monetary values and do not have a long-term effect. A forced nominal devaluation of a new domestic currency in Greece would even start a vicious circle again and a lower pressure on the needed reforms.

So this whole text shows again that anybody in the world wants to convince anybody else of any nonsense as long as it seems prudent. And Mr. Henkel in Germany does the same.

Perhaps I am of the same kind, too .)-

Posted by:

LVM - Bravo! You are 100% correct. The issue with Greece is that taxes have increased AND the government is cutting spending AND massively increasing the amount of interest paid to foreigners.

There is only one outcome to this formula.

Less money because of higher taxes

Less money because the government is giving back less.

Less money because it is being sent abroad to service the government debt.

In short, if you wanted to cripple an economy and totally control a country, "the measures" are EXACTLY what you would do.

The government needs to take responsibility for its incompetence and default on its debt COMPLETELY and take the taxes back to what they were 20 years ago.

-

-

Posted by:

The Greek crisis can not recover unless all those reforms that all reasonable people deem necessary are realized. Whenever Greece goes back to an independent currency (without reforms) that currency will continuously devaluate up to hyperinflation.

Imports of oil and other products will then become extremely expensive!

There have now been lost many years with an increasingly suffering population without any use... -

Posted by:

Could you please add a link to the Morgan Stanley report? Thanks!

-

Posted by:

This is exactly the issue which Hans-Olaf Henkel of Germany has been pondering for a long time ("The Euro is too expensive for France and too cheap for Germany"). Henkel even goes so far as to argue that, longer term, the cheap Euro is bad for Germany because it diminishes German efforts to increase productivity and innovation. In short, the Euro makes it too easy for German businesses to export.

Henkel advocates a departure from the Euro by Germany and the other hard-currency-countries; i. e. the North (except France). That would be good news for the South more or less immediately and, after some adjustment shocks, good news for Germany in the long run, too.-

Posted by:

"There is much to be debated about the prices’ resistance to falling at the same pace as wages, and it is often one of the troika's arguments that there is not enough competition in the products markets. However, aside from the fact that prices are known to be sticky downwards,"

The reason prices have not fallen is that the cost of living has increased. How are price supposed to fall if petrol is more expensive, if people are having to pay more property taxes and income taxes? Where is the extra money going to come from to pay these taxes if the income of businesses goes down because of falling demand and reduced profit margins?

And as a side note. This talk of expensive Euro in Greece and cheap Euro in Germany is complete and utter garbage.

A currency is a measure of wealth. To criticise the Euro is akin to criticizing kgs. To use an analogy. The reason Americans are overweight is not that they are fat but that kgs are too small a measure for the American body. The kg needs to be different to the kg in Europe.

Of course a completely stupid argument and yet it is one apparently intelligent people have about currencies.

Again, kg as a measurement is not the problem, it is measuring the facts and in the case of Greece, the Euro is telling us that the economy is massively inefficient.

A cheap Euro or expensive Euro is not going to solve the issues in the Greek economy i.e. government red tape in employment, in pensions, in starting a business, in closing a business, in bankruptcy, in the legal system, in property ownership, in the tax system etc etc.

Changing the currency is not going to change the fundamentals it is only going to change the way things are measured.

The only thing the Drachma would do for Greece, is allow the government to disguise its inefficiency behind the camouflage of inflation. Nothing more.

The Euro is forcing the Greek government to face its incompetency, unfortunately, the Greek government is refusing to change and i

-