We can't ignore population shifts within the European Union

I have written a book on the macroeconomy of Greece, and another book on the macroeconomy of the Netherlands.[1] These books are forward looking and start with an analysis of the demographics of each country, and what this could mean for the future availability of labor in each country. Demographics are a fundamental force in all economies. They determine in part how big the real GDP of a country can become in the future.

In doing the research for these two books, I came upon an intriguing (and unexpected) phenomenon: the populations of the EU countries are slowly but steadily on the move. Greece is in the south-east corner of the EU and losing population. The Netherlands is in the north-west corner of the EU and gaining population. Greece is growing slowly (recovering) and aging fast, with steady current account deficits and high public debt stress at over 200 percent of GDP. The Netherlands has, so far, maintained relatively sound growth, managed aging in the welfare state, with steady current account surpluses and debt below 60 percent of GDP.

Thus, to some extent, the underlying demographic and economic dynamics of Greece and the Netherlands seem at opposite ends of the geographic diagonal in the EU from south-east to north-west. The root causes of these differences fundamentally rest with government policies (relatively adversarial in Greece, relatively consensus based in the Netherlands), trust in the institutions of the State (relatively weak in Greece, relatively strong in the Netherlands), and cultural aspects of how society works (relatively individualistic in Greece, relatively cooperative in the Netherlands). The point of this blog is not to dwell on the current different challenges for each country (which will gradually change over time), but rather to ask whether these differences are a cause of population movements in the EU more broadly.[2]

In fact, upon further investigation, it appears that from the eastern border of the EU (from Estonia to Romania), then down to the Balkans and into Greece, and on the southern border of the EU (from Italy to Portugal), almost all countries are gradually losing population from emigration to other countries inside the EU. The relative opposite is happening at the other ends of Europe in the north and west of the EU, from Finland to Norway on the northern border, down via the Netherlands to Belgium, France on the western side of Europe, with immigration from other countries in, and into, the EU and Europe more broadly.[3]

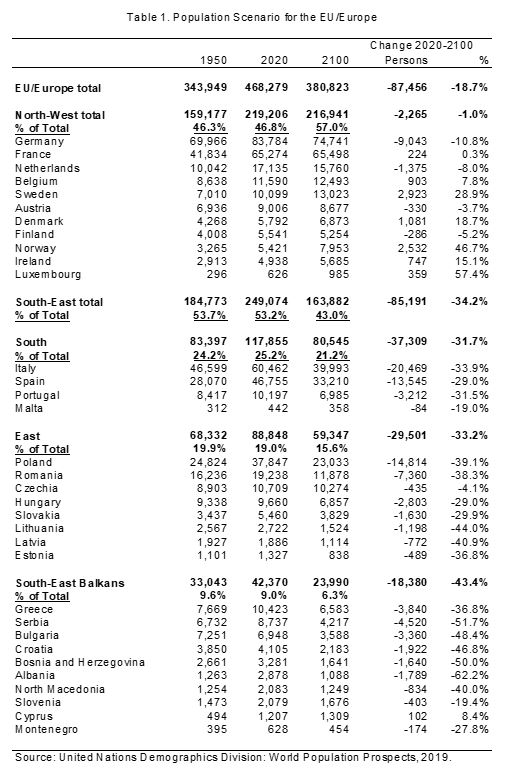

Thus, it would appear that since the development of the EU as a common market for labor, goods and services, as well as capital, (younger and better educated) people have been moving from the east and south to the north and west. Table 1 below presents the data per country and as classified by larger country groupings. All data are from the United Nations 2019 World Population Prognosis, central scenario.

Between 1950 and 1990 the populations grew in most countries of Europe, consistent with the baby boom generation and the recovery from WWII. Then came the fall of the Berlin Wall and the Iron Curtain in the early 1990s, whereupon the eastern European countries opened up and started to lose population quickly, most of them migrating into western Europe. Through the early 2010s, Spain and Italy attracted immigrants from Latin America, reflecting cultural affinities and historical ties, which boosted their populations. But, this trend has reversed in the last decade and the southern range of the EU is now also losing population.

The population of Europe, as defined in table 1, grew from 344 million to 468 million people between 1950 and 2020. The UN projects a decline of 87 million people by 2100, or 18.7 percent of the peak population in 2020. The forward looking regional differences are stark. Hardest hit is the south-east around the Balkans with Greece as the biggest country. It is expected to lose over 18 million people, or 43 percent of its base in 2020. Eastern and southern countries are looking at the prospect of losing a cumulative 67 million people or over 30 percent of the 2020 base. In contrast, the north-west is expected to lose 2 million people, or 1 percent, of which a loss of 9 million people is expected to concentrate on Germany alone, which has low fertility rates and is advanced in aging.

The data can change and new projections emerge with time. The UN is expected to come up with a new prognosis sometime in 2021. The Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) in the Netherlands has just updated its own long-term demographic projections, and it now expects the population of the Netherlands to keep growing in this century. By 2100, there may be 4 million more inhabitants in the Netherlands, rather than the 1.4 million loss in the 2019 data from the UN, in Table 1. The CBS notes explicitly that many immigrants to the Netherlands come from other EU countries, and this trend is expected to continue now that the UK has closed its borders (previously the Netherlands was a pass-through to the UK, especially from Poland and other Eastern EU countries; now the Netherlands is even seeing some immigration from the UK). If the UN confirms this trend, then the dichotomy in the big regions within the EU will only get bigger.

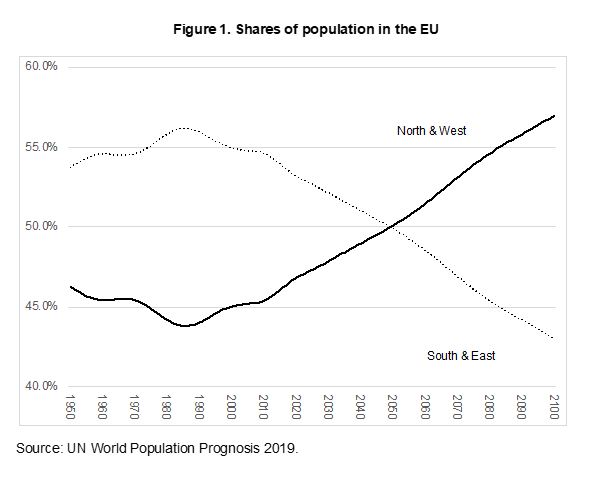

Finally, to bring home the divergence in demographics within the EU/Europe, one can divide the continent in two groups: the north-west and the south-east groups. In the past, the south-east group had a larger population, and was more population dynamic, than the north-west group (Figure 1). Since the 1990s, this has reversed, as noted above. The north-west countries now have stronger economies and, according to Gallup World Poll data, generally show a higher level of trust in politics and government institutions.[4] That may contribute to a migration of population out of the south-east regions to the north-west regions. The share of the total population concentrating in the north-west regions is expected to grow steadily in this century, while that in the south-east regions is expected to wane.

Looking ahead to the future, one wonders if the implications and, indeed, challenges, from these demographic trends are underestimated by policy makers. The EU leadership does not appear to fundamentally factor these prospects into the discussions of politics and the economy of the EU going forward. Aging and how to protect the welfare state in each country is always on the agenda. There is also a cottage industry of politicians in Europe that beats the drums about “convergence” of the standard of living in EU countries. The EU Commission, in its long-run fiscal sustainability reports appears even to assume that convergence will take place, even if there is uneven evidence that this is taking place in a sustainable way. Considerations of convergence are well-intended, but may not address the most pressing policy issues.

The population movements inside the EU are a serious issue that deserves further thought and debate.[5] No one (except for UK populists) is suggesting that internal mobility should somehow be restricted[6], but countries that lose population will see a dilution of population density and hence likely a loss of economies of scale and other adverse effects on productivity and the standard of living. What is more, several countries in the south-east group are also at risk of, or are already exhibiting, a low growth rate and high public debt compared with countries in the north-west group. With slower future growth, debt sustainability will only get more difficult for them. Politically, the more populous groups will also gain power, which could be causing some anxiety in the south-east group. In this context, while convergence and solidarity remain relevant and important, countries that do well in the future, will likely do so based on the achievements of the domestic political system. Assumptions about convergence or solidarity (from outside) are unsound bases to build strong sovereign high-performing countries.

Policy implications. A broad public dialogue about long-term demographic dynamics will be helpful to generate ideas for policy options. Society’s preferences will also become better defined, and that is crucial to gauge the acceptability of these policy options. For instance, some countries may be more open to immigration, including taking in refugees, than others (as is already the case among EU member states). I assume that most agree that coercive population policies or imposing social and medical choices should be avoided to guard against creating dystopian conditions.

Consistency is crucial: population dynamics are long-term forces that cannot be reversed or turned around in the short run. Demographic scenarios should be taken seriously and not assumed away or ignored when we make plans for the future. In fact, they deserve to be the bedrock for long-run economic and fiscal planning. Creating a sound/balanced economy starts by assessing and respecting the forces of demography and women’s reproductive choices.

Some policies can support fertility, but only in the margin. Good reproductive health care and information are important. Social infrastructure such as parental leave policies and availability of day care facilities are also important, including to support (female) labor participation. Most analysts expect in our EU countries that fertility rates will remain below replacement, which implies that populations will grow or decline based on net migration and integration policies.

What induces people to move to another country? Politics, employment prospects, and justice. While some public actors have a talent for conspiracy theories to blame others and gaslighting large swaths of the public some of the time, in the end, individuals on average have a good nose for smelling true unfairness in society. If this becomes endemic, or morphs into strong clientelism or outright insider/outsider institutions, or gender or sex discrimination, etc., then trust in society and politics will deteriorate. This sets up a leakage of energetic and talented people to seek their fortunes abroad: they vote with their feet.

This is how political systems compete: do the citizens trust the politicians and the justice system, or not? If not, net migration will likely turn negative.[7] Everything is relative, and no country is free from problems, but moving to another country is a big step, and individuals/families don’t make such choices lightly. Quality politicians do not worry about discussing these issues, in fact, they will welcome the public dialogue. They provide honest, fact-based and level-headed assessments, as they see it and document it, what the economy can likely deliver in the future for next generations. They eschew promises that taste good in the short run but exceed the carrying capacity for society to support and finance in the long run. Unwillingness to pay for what we want today, and instead loading young generations with debt does not fit this bill. At the end of the day, it is policies in different countries that matter, not where we are born.

*Bob Traa is a macroeconomist and author of "The Macroeconomy of Greece: Odysseus' Plan for the Long Journey Back to Debt Sustainability" published in 2020.

[1] Bob Traa: The Macroeconomy of Greece, and Bob Traa: The Macroeconomy of the Netherlands (both books are available on Amazon.com).

[2] The cycles may be changing in both countries: the Netherlands has had some good years, but may experience somewhat more challenging times in the near future (the Dutch so-called “Polder Model” is getting older). Greece has gone through a crisis, but may experience somewhat more favorable years in the near future as the recovery intensifies. The relative fortunes of countries often go back-and-forth.

[3] Norway is not an EU country but is included because of its likeness with the north-western countries in respect of demographics. I also include the Western Balkans as candidate countries for EU membership. I exclude the UK because of Brexit which has stopped the freedom of movement of EU citizens.

[4] The Gallup World Poll is a key source for the United Nations World Happiness Reports, published since 2011. These reports broaden the scope for well-being beyond real GDP per person and are well-worth reading.

[5] Palgrave (2021) has recently published two interesting volumes on the experience of the 11 EU enlargement countries from Eastern Europe. The “migration channel” of economic adjustment was found to be important, especially as interacting with developments in foreign direct investment and institution building: “Does EU Membership Facilitate Convergence? The Experience of the EU's Eastern Enlargement - Volumes I&2” Editors: Landesmann, Michael, Szekely, Istvan P.

[6] The COVID pandemic also has brought some restrictions, but these are expected to be temporary and for obvious public health reasons.

[7] Some political systems are so afraid of this response by the public to their policies that they prohibit citizens from leaving the country. This was notorious under the previous Soviet Union, and still is in North Korea. It is also a concern for the future of the new Afghanistan where it is not yet clear whether those who wish to emigrate will be allowed to leave the country.

Podcast - Whose property? Greece’s housing challenges

Podcast - Whose property? Greece’s housing challenges Can the Green Transition be just?

Can the Green Transition be just? Where is Greek growth coming from?

Where is Greek growth coming from? Bravo, Bank of Greece

Bravo, Bank of Greece