A closer look at Greece's Q3 2023 national accounts

ELSTAT has just published an update for the Greek national accounts through the 3rd quarter of 2023. Since this summarizes the whole economy, it is helpful to see what the data can tell us.

In brief, economic activity in Q3 remained at the same level as in Q2 (seasonally adjusted).

Relative to 2022-Q3, real GDP increased by 2.1 percent. This means that real GDP may grow by 2 percent or slightly above for the full year 2023.

Since employment growth remains buoyant and unemployment is coming down, with inflation gradually easing, and despite continued external shocks, this is a satisfactory result for Greece.

Most banks and other cyclical commentators, who provide interpretations of the data and look ahead to the next year or so, move from these headlines to the next level of detail to assess the growth in consumption, investment, exports, and imports.

The government and the public at large are likely to do the same. If any of these aggregate demand components shows weakness, or incipient weakness, there may emerge thoughts that “monetary policy is too tight,” or the government should “take fiscal measures to support the economy.”

Jumping to conclusions on the basis of aggregate demand components alone is risky. A more balanced analysis will reveal a richer understanding of why the economy is doing what it is doing, in its international context. And, the focus of policy attention may then shift to other levers in the toolbox, rather than always thinking of credit and fiscal stimulus.

From the first days that I worked on Greece, I have had a sense that Greece does not have an aggregate demand problem, as though there is a deficiency.

Rather, Greece has permanent excess demand, relative to aggregate supply. This is visible in the lasting deficit in the external accounts; incipient pressure on domestic prices and the cost of living; a tendency toward high fiscal deficits and debt, among other signposts.

In other words, the problems are on the supply side—Greece needs to focus on efficiency and productivity, rather than on spending stimulus.

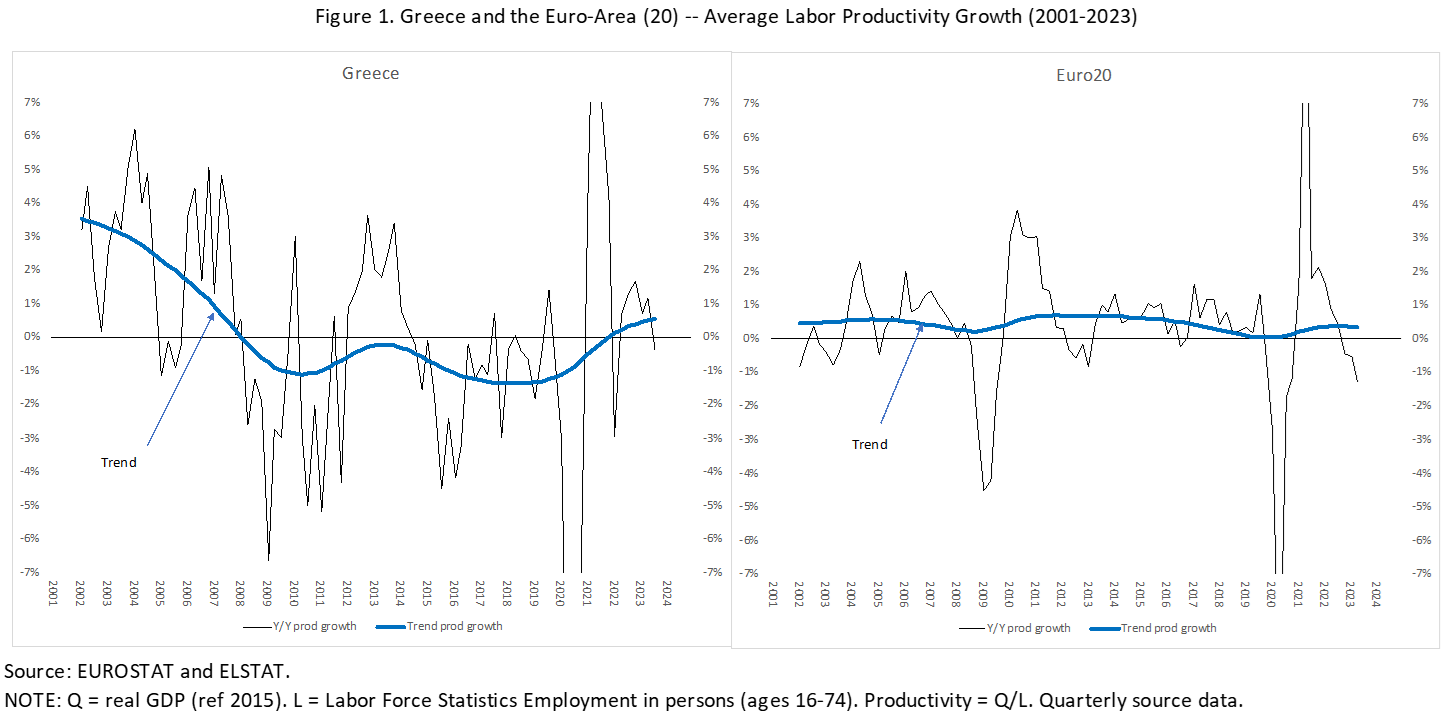

Consider Figure 1 below, which compares Greece and the Euro(20) countries as a group. Real GDP is computed from quarterly data as the moving sum of the past 4 quarters (“annualized” on a quarterly basis). The number of workers in the countries that produced this real GDP is measured with quarterly data from the labor-force survey: the average number of workers (16-74) in employment over the same past 4 quarters.

This allows us to compute average labor productivity as the ratio of real GDP over employment—it tells us output per worker (all employment categories included), or how efficient each worker is over time.

The thin line in the Figure shows the growth rate of productivity year-over-year (Y/Y). The trend line is a smoothing function (HP filter with l=1600) to take out noise in the ups and downs of the data—to help see the longer-term underlying evolution of productivity. We can make some observations:

- Trend productivity growth in Greece has recovered to a positive number. This is good progress

- Trend productivity growth in the Euro(20) halted twice (2009; 2020), but never became negative for the currency union as a whole.

- The average Y/Y productivity growth rate for Greece for the period 2001-2023 is 0.1 percent a year; the average for the Euro(20) is 0.5 percent a year.

- For 2023 alone, the trend productivity growth rate for Greece is now at 0.5 percent; 0.3 percent for Euro(20)—this is consistent with the sense that Greece is doing slightly better than the Euro as a whole in the rebound from Covid.

- However, recent quarters both for Greece and the Euro(20) point toward a new dip into negative productivity growth rates. The economies are slowing down, while employment growth is still holding up for now—this moves productivity growth rates down. It is consistent with the finding that the labor markets always react with some lag to real GDP growth, due to friction costs.

What are some of the policy considerations that flow from this information?

- Caution is warranted when assuming high productivity growth rates into the future. High rates would help, because they boost potential output growth. But, neither the Euro(20), nor Greece, have managed high productivity growth rates on average in the past.

- Employment growth may slow in the future, even though Greece still has a reservoir of unemployed to absorb. Moderation in wage policies (bounded by productivity growth), until unemployment is much lower, is advisable for Greece—for now maintain a preference for employment over income growth.

- Will “green investments” boost productivity growth? This is not assured. Some governments in the renewal of the SGP and the new rules for the Maastricht Criteria are clamoring for “more fiscal space” to boost green investment. But, this is again unilateral aggregated demand thinking. Sure, when you boost investment spending, real GDP may go up, but does replacing a gasoline engine with an electric one deliver a bigger real GDP in the future, or is this a retooling without significant fundamental productivity gains?[1]

- The green spending (a better word than “investments”) is important and necessary, but we may have to pay for it now, rather than borrow against a supposed future additional real GDP that may not come. Can our political systems, can our societies, manage this challenge?

- In 2023 (Q1-Q3) the average real output per worker in Greece was €46,000 (ref 2015). For the Euro(20) as a group, it was €75,000. This 60 percent productivity gap is big and explains largely why average wages in Greece cannot be the same as in the Euro(20).

- The path to closing this gap is not cheap credit and higher fiscal deficits and debt. This requires real structural reforms, such as breaking open domestic protected markets, stripping out of legislation and regulation any provisions that favor certain groups over others, strengthening property and foreclosure rights, speeding up the functioning of the courts, making politics more transparent, etc. Can Greece deliver truly contested domestic markets that attract new domestic and foreign investors at a scale that makes a difference? The balance of payments, and pressures on the cost of living, and on fiscal spending, will give us future indications whether trend productivity is increasing at a pace high enough to warrant a rise in real wages and the shared standard of living.

- In short, focusing too much and narrowly on aggregate demand components when analyzing quarterly GDP numbers is not advisable. Illuminate developments on the supply side, and underlying structural conditions, as well. And we have left out a third approach, which studies the distribution of GDP among capital (operating surplus), labor (remuneration), and the government (indirect taxes minus subsidies). Here, Greece is quite different from its Euro(20) peers as well, and this presents yet another fascinating set of ideas. Alas, no-one said that governing a country is easy…

[1] There could even be efficiency losses in some industry from the need to go electric or zero emissions.

Podcast - Whose property? Greece’s housing challenges

Podcast - Whose property? Greece’s housing challenges Can the Green Transition be just?

Can the Green Transition be just? Where is Greek growth coming from?

Where is Greek growth coming from? Bravo, Bank of Greece

Bravo, Bank of Greece