Are you not entertained?

The tone of the day is celebratory for some. After eight years, myriad Eurogroup meetings that lasted until the early morning hours and hundreds of billion euros in loans, the eurozone is probably happy that it doesn’t have to spend any more time, energy and money on this small country at the corner of Europe that represents 2 percent of the total eurozone economy.

The Greek government naturally attempts to maximise the public relations aspect of the completion of the programme as it is essentially the only narrative it has left after the calamitous first months in office and the failure to deliver on any of its unrealistic promises that got it to power in the first place in January 2015, and won it the second term in September of that year.

However, if a crisis management response is to be measured against the outcome then it is natural that the mood of celebration is not shared by the average Greek, and this is not because the last decade has sapped hope.

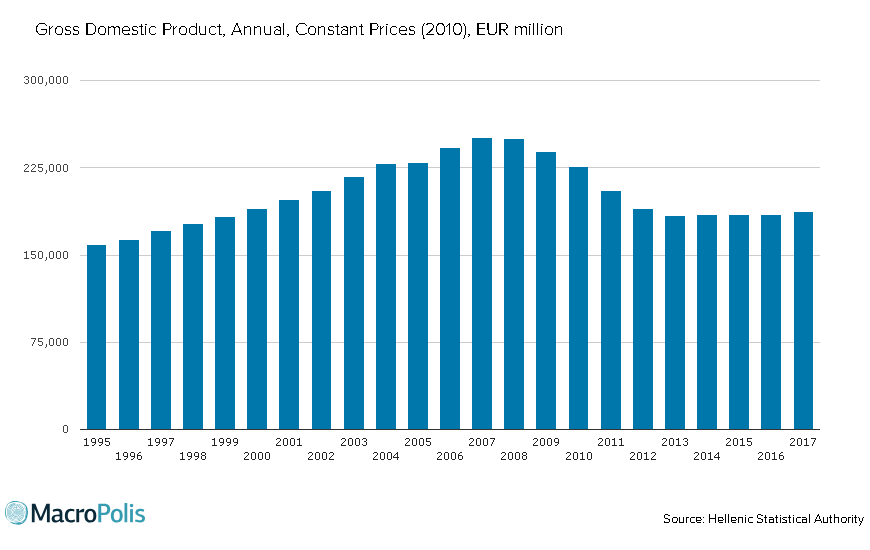

GDP decline

Greece’s real GDP in 2017 was close to 64 billion lower than the pre-crisis levels.

This drop of 25 percent in output is mostly driven by a complete collapse in domestic demand, particularly in the first years of the crisis.

Private consumption

Private consumption in the 2008 – 2013 period dropped by nearly 44 billion euros, losing a quarter of private spending in just half a decade.

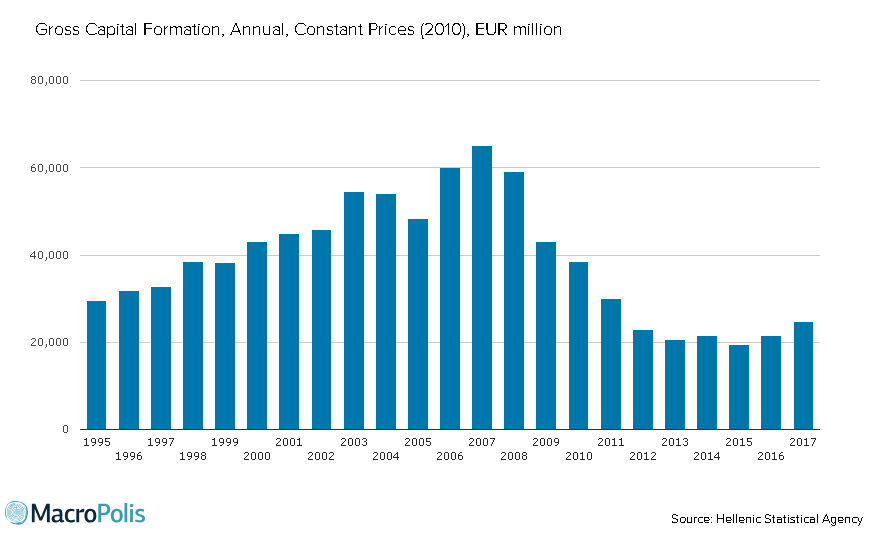

All types of investments, from property to industrial equipment were severely impacted by a complete lack of credit and ongoing uncertainty. Capital formation just collapsed from over 65 billion in 2007 to 20 billion in 2013, a drop of close to 70 percent.

The rebound over the last couple of years simply underlines how damaging the ongoing threats and speculation of Greece dropping out of the euro were for the Greek economy.

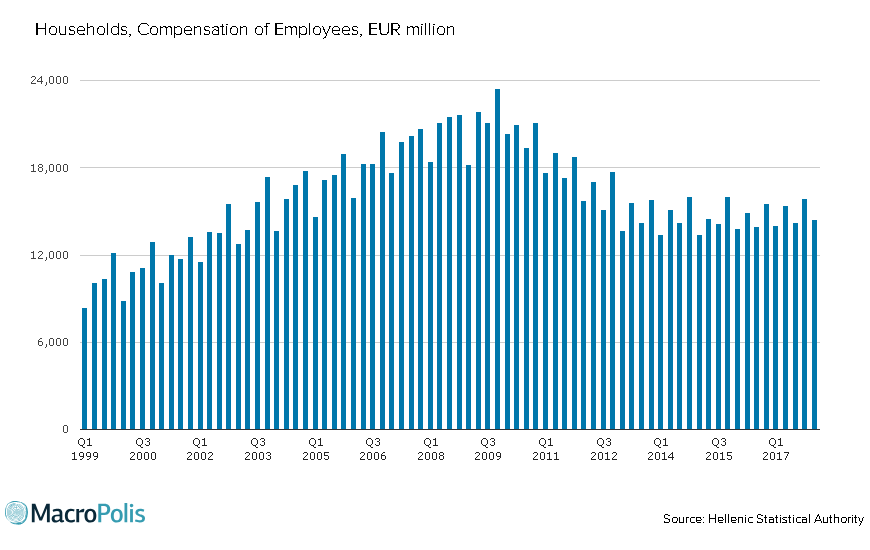

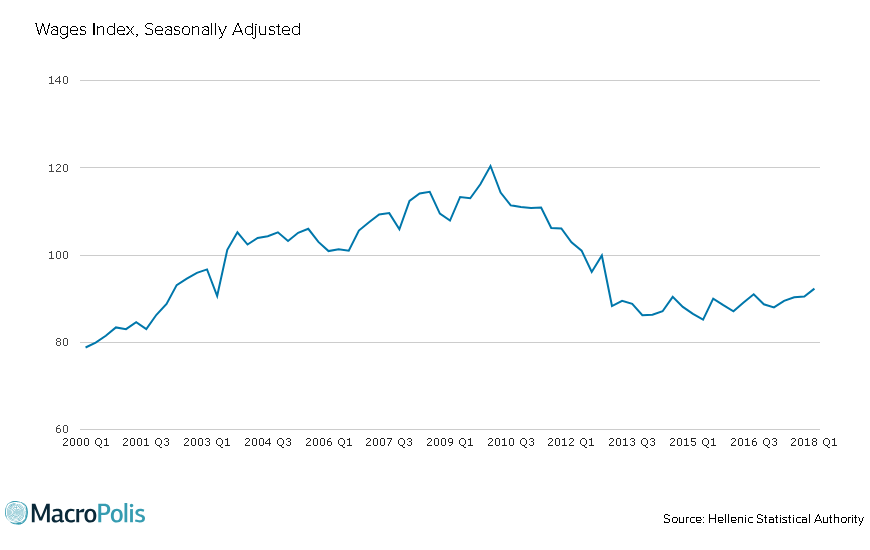

Wage reduction

Greece’s lenders had identified a significant competitiveness problem that translated into an overvalued real effective exchange rate by close to 30 percent and a current account deficit of 15 percent. In the absence of any other policy leavers, the solution of ‘internal devaluation’ was selected that went after Greek wages forcefully, reducing the minimum wage and other sector wage agreements by close to a quarter.

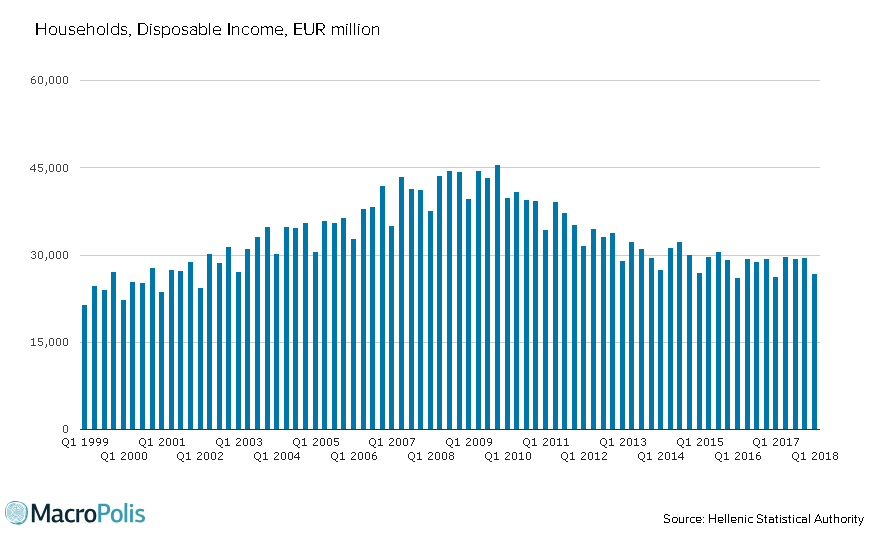

Compensation of employees between the last quarter of 2009 and the end of 2013 went down by nearly a third to 15.8 billion. Disposable income in the last three months of 2009 stood at 45.6 billion, in the last quarter of 2013 it was under 30 billion, a 35 percent drop.

The index of wages in the middle of 2015 was almost 30 percent lower than the first quarter of 2010. Although having partially recovered since, on aggregate Greeks take in 23 percent less than they did eight years ago.

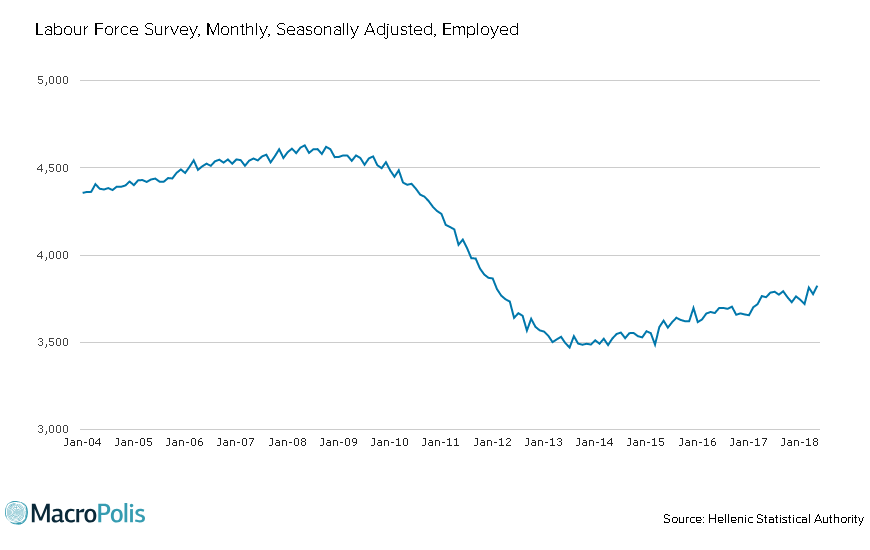

Job losses

At the same time, each month jobs were being lost by the tens of thousands. By the time job losses bottomed down in July 2013, close to 1.1 million jobs had been lost since September 2009, an average of close to 24,000 new unemployed each month. The recovery in the job market has been mostly driven by seasonal jobs in the tourism sector and largely by part-time and shift-work that pays close to the poverty threshold. Part-time employment has reached nearly 360,000, up by 100,000 from the pre-crisis levels. Still, 740,000 Greeks remain out of employment since the crisis started.

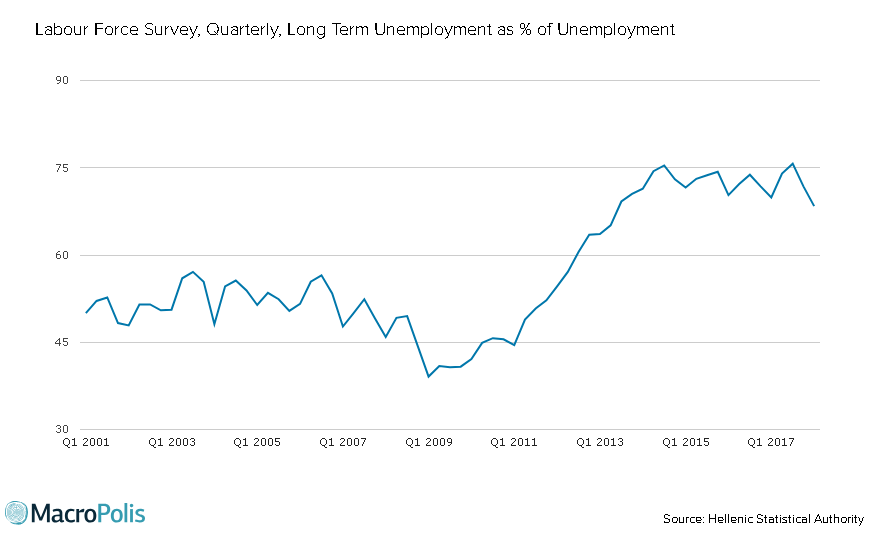

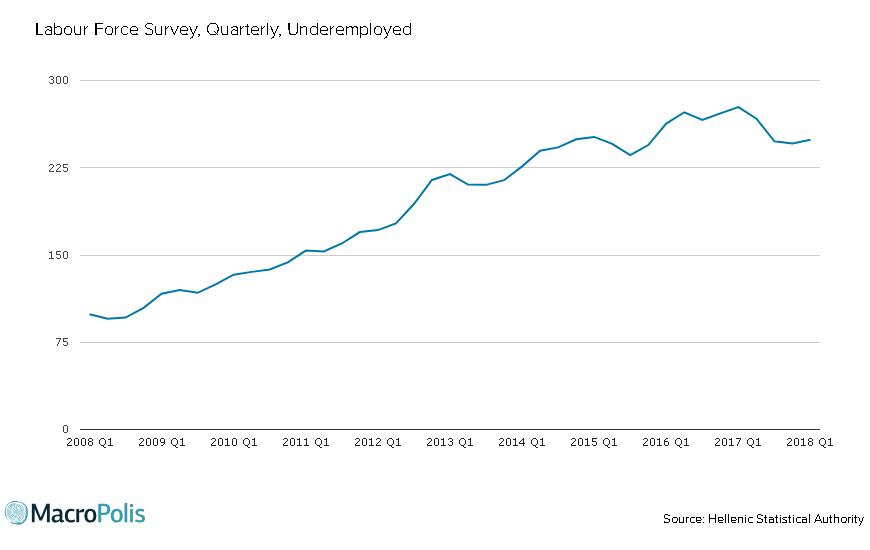

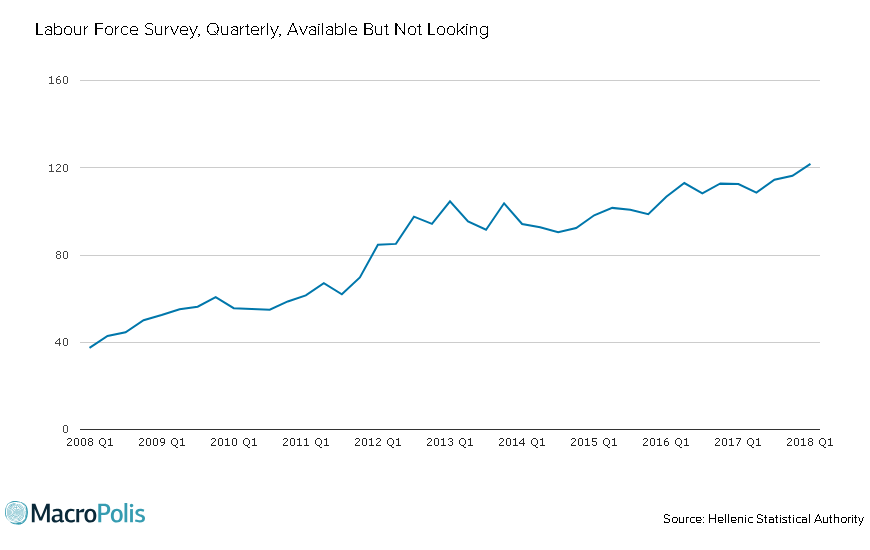

To make matters worse, almost seven out of 10 unemployed have been unemployed for more than one year with very few prospects of employability, while close to a quarter of a million of those in jobs are underemployed in the absence of adequate full-time employment. Discouraged workers, available for employment but not looking and hence not counted in the unemployment rate, have reached an all-time peak of close to 122,000.

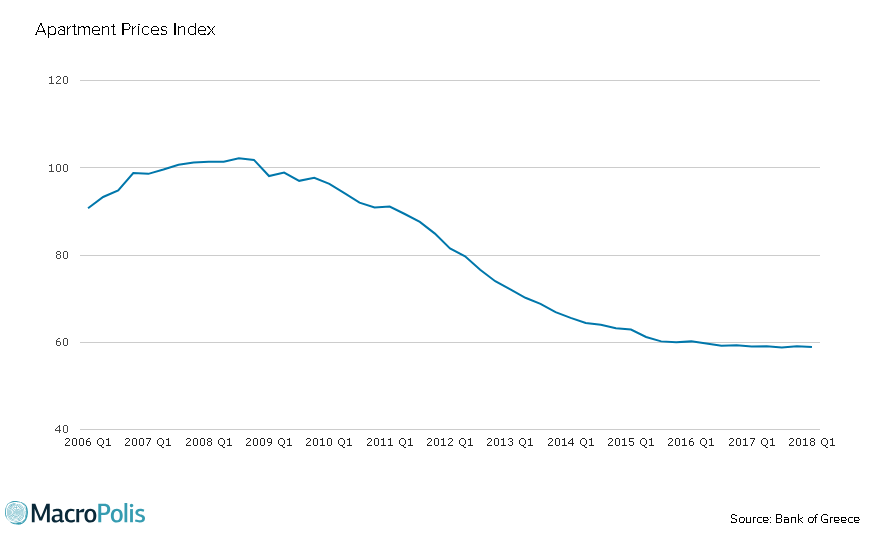

Property prices

Greeks did not lose just income, the crisis destroyed wealth across the board. Houses have been traditionally seen as the preferred asset to direct savings since the high inflation days of the national currency. Property ownership was pushed up by abundant and cheap credit since the introduction of the euro. Property prices, though, have collapsed since 2008, with the index losing close to 40 percent by 2015. This had a knock-on effect on servicing mortgages, the collateral banks on their books and even loans of small businesses that were backed by property.

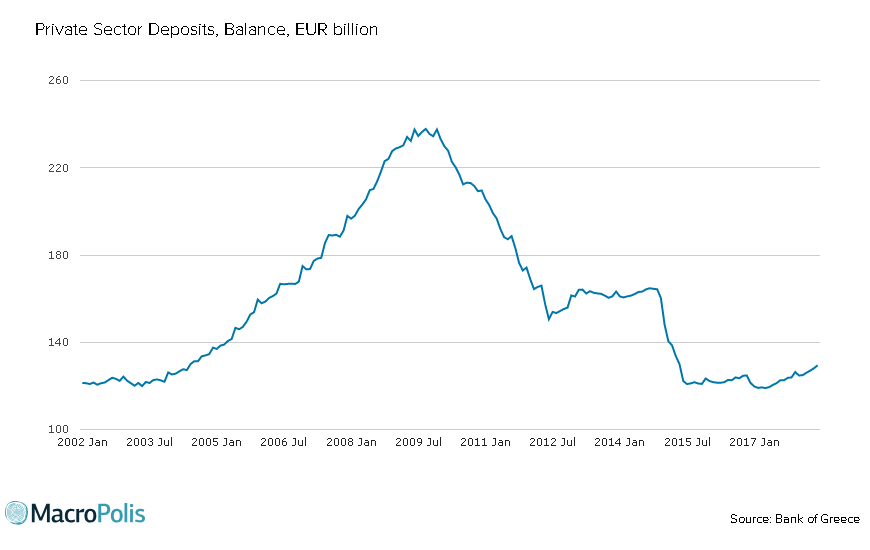

Deposit flight

The banking system, aside from having to deal with the major issue of loan quality deteriorating, also had to contend with a massive capital flight that translated into people moving their money out of the banks in two major waves, one between the end of 2009 and June 2012 when close to 87 billion euros left the banking system and the second in the first half of 2015 when almost 42 billion euros were withdrawn. Following a recovery in the last couple of years, the deposits base of Greek lenders is lower by 108 billion, almost reduced by half. Greeks banks and their ability to finance Greece’s growth is seen as a sensitive link in Greece’s recovery by international organisations and rating agencies.

These eight years have left Greece’s economy and Greeks deeply scarred. The recovery over the last couple of years has been too modest to be widely felt. Facing an uncertain future, with trust in domestic politicians gone, belief in European institutions shaken, shattered and poorer the celebrations for Greeks will probably have to wait.

1 Comment(s)

-

Posted by:

Thanks for the in-depth analysis. I would be curious to learn how the informal sector evolved over the last eight years (at least through estimations). This probably requires a clear definition of what is the informal sector in Greece. For instance, doesn't a sale by a formal business without VAT collection already fall under that scope?

Podcast - Whose property? Greece’s housing challenges

Podcast - Whose property? Greece’s housing challenges Can the Green Transition be just?

Can the Green Transition be just? Where is Greek growth coming from?

Where is Greek growth coming from? Bravo, Bank of Greece

Bravo, Bank of Greece