-

Is the Greek green transition running out of power?

Is the Greek green transition running out of power?

-

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

-

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

-

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

-

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

-

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

The wrong prescription

As is customary by now the troika’s return to Athens has been accompanied by a flurry of speculation about how targets will be met. This time the focus is on the structural rather than fiscal side. This simply means replacing the back and forth between Greece and its lenders over excruciating details of how money will be saved with a similar tug of war over the minutiae of reforms.

The current round of talks includes haggling over the recommendations made by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). The Paris-based body made towards the end of 2013 a series of recommendations, known as a tool-kit, for improving conditions for competition. The OECD identified in November 555 regulatory restrictions which it believes undermine competition and it made 329 recommendations on legal provisions that should be amended or repealed. It says this would add several billion to Greece’s economy. The troika expects Greece to adopt all the recommendations. The government has said it will implement around 80 percent of them.

There is much that is constructive in the OECD’s tool-kit in terms of dismantling age-old bastions against competition but there also seems to be a lot of nit-picking. Some changes appear to bring little financial benefit and may, in fact, end up costing more in other respects. One of these is the OECD’s proposal that over-the-counter (OTC) medicines should not just be sold by pharmacies but should also be available in supermarkets and other stores.

The OECD suggests that this liberalisation would bring down the price of OTC drugs and reduce costs for consumers because they would be more widely available. It cites examples such as Italy, where prices of such medicines fell by 6.6 percent after liberalisation in 2006-7. Prices fell in other countries too. However, the OECD also gives the example of Portugal, where allowing OTC drugs to be sold in various retail outlets in 2007 left prices “largely unchanged.”

The reasoning behind the OECD’s recommendation is summed up in the following paragraph: “Making OTC medicines and dietary products available only in pharmacies also has an impact on the ease with which a consumer can purchase a pharmaceutical or dietary product. Disallowing channels such as supermarkets, convenience stores and petrol stations makes the distribution network for OTC products sparser. This increases welfare costs to consumers, as they cover a longer distance to make their purchases, spend more time in the process and incur travelling costs.”

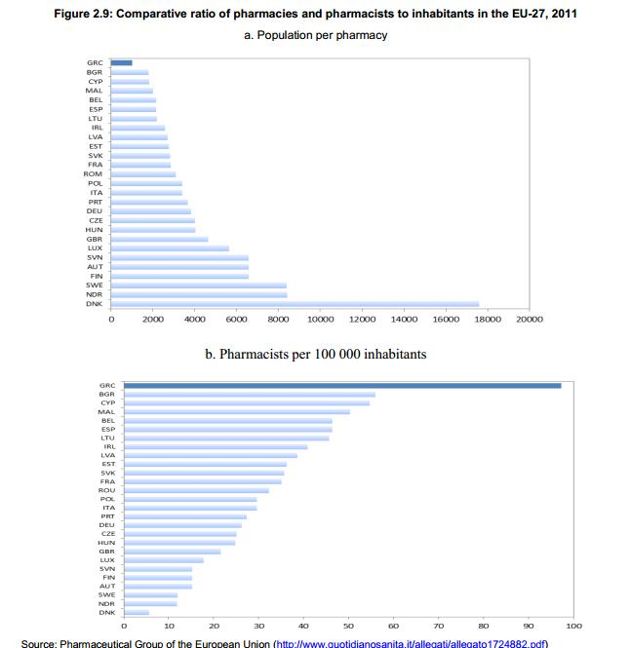

This explanation appears on page 100 of the OECD’s document. Eight pages further on in the same report there are two tables that show Greece has the largest concentration of pharmacies and pharmacists in the European Union:

As anyone who has spent any time actually experiencing Greece rather than the inside of a hotel or meeting room will tell you it is easier to find a pharmacy than a super market or convenience store. The argument that OTC medicines need to be made more widely available holds no water in the Greek case.

Perhaps there is more of an argument to be made, though, in other areas, such as pharmacies’ opening times and profit margins. Opening hours have been liberalised but pharmacists have only made tentative steps in changing their outdated timetable, which sees their stores close at lunchtime every day, on Monday and Wednesday afternoons and on weekends.

With regards to profit margins, pharmacists in Greece receive 24.3 percent of the final retail price for non-prescription drugs, which is 4.8 percentage points higher than the EU average, according to the OECD report. Perhaps there is a little wiggle room here for prices to come down. This might not even need any great intervention. Making larger packages of some OTC medicines available would help, the OECD indicates.

“The unfavourable performance of Greece in terms of price is also greatly influenced by the fact that, according to data provided by Minte Ltd. (2013), packages containing a larger number of pills are unavailable in Greece,” says the organisation’s report. What the OECD fails to note, though, is that the sale of OTC drugs provide a significant cash injection for Greece’s troubled pharmacies.

At first glance, these drugs seem a minor part of the Greek market. In 2012, they accounted for just under 12 percent of the total sales of medicinal products, compared to an EU average of 16 percent. Sales of OTC drugs were worth 372 million euros in 2012. Yet for most Greek pharmacists, this money is a lifeline.

Along with cosmetic products, OTC drugs help provide them with money to keep their stores open and employees in jobs. Their profit margins on prescription medicines were generous in the past but has been minimised to about 6 percent (pre-tax) now. They also have to wait up to six months for social security funds and healthcare provider EOPYY to pay their share of medicine costs. The OECD also makes no mention of the fact pharmacies have to pay a rebate and suffered losses in the 2012 PSI on the Greek bonds the government used to pay them. This forced many pharmacists to take out loans to keep their businesses afloat, loans which carry an interest rate of close to 10 percent. If they are to compete with supermarkets, it hardly seems a fair contest.

Ultimately, this comes down to a question of survival. The OECD itself makes it clear in its report that liberalising the sale of OTC medicines could lead to pharmacies closing. “Theoretically, it is possible that the revenue stream of some pharmacies in a liberalised market scenario would not be sufficient to cover their overhead costs,” the organisation says. For the Paris-based think tank this represents the natural order of things. “In a competitive market there are winners and losers,” OECD Anna Thiemann told Kathimerini in an interview recently.

The problem is that in this case we are not talking about conventional market conditions. In Greece, pharmacies are rarely just retail outlets, they are usually neighbourhood and community reference points, institutions if you like. Unlike other parts of Europe, Greeks often go to pharmacies for more than just picking up a box of aspirins or bottle of antibiotics. Pharmacists are impromptu family doctors and health counsellors. In each neighbourhood, they will know the medical history of their regular patients, provide advice and basic but crucial services such as performing jabs and taking elderly people’s blood pressure. These are not services you can get at super markets or petrol stations.

Given that the lack of access to healthcare is becoming a burning issue in Greece, serious thought should go into how to protect pharmacies. As the government shuts down health centres, pharmacies are starting to take on some of their basic tasks.

The OECD has been faithful to an economic orthodoxy in compiling its proposals for the Greek market that resembles the “one size fits all” approach that has blighted the country’s adjustment programme. There is no reason why Greece should unquestioningly adopt these suggestions, which include adulterating its high quality olive oil.

There is no reason for the troika to insist that Greece takes a blanket approach to the OECD’s recommendations. “Full implementation of the OECD recommendations would send an important message on the willingness and ability of the Greek Government to pursue successfully critical growth-enhancing structural reforms,” troika officials wrote in an e-mail to Greek Development Minister Kostis Hatzidakis in January. It is difficult to see how this message would emanate from the sale of non-prescription drugs in super markets, just as the advantages of producing poorer quality olive oil are not clear. Meanwhile, the social impact of such changes has not been factored in at all.

Greece’s challenge is to come up with a way of removing unfair barriers, wriggling free of vested interests and improving efficiency while maintaining practices that give added value to Greek society, not just the market. It is a reflection of the poverty of Greek politics that there is no local response to the OECD's proposals. Where is Greece's alternative vision for a more competitive economy that preserves vital social links?

These kind of changes need the precision of a surgeon armed with a set of scalpels rather than the brawn of a mechanic dipping into his "tool-kit." Perhaps these are mere details in the general upheaval of the Greek crisis but it is on such details that societies are altered for ever, and not necessarily for the better.

2 Comment(s)

-

Posted by:

"This short description proves that the text of Mr.Malkoutzis is not well balanced."

Au contraire, your short description proves nothing except that you refuse to understand Malkoutzis' argument since it goes against your ideology.

Apart from failing to address his points, more tellingly your description completely fails to address the peculiarities of greek reality - in which half the population of the country lives in small island and mountain communities without supermarkets and chain stores. -

Posted by:

This is a perfect example to discuss how a certain reform does change economy.

If you have a too big number of pharmacies with everyone having minimum fixed cost then buying medicine costs much more and the amount of free money for households decreases accordingly.

Also, pharmacies have higher gross margin than efficient supermarkets. This has the same negative effect.

On the other hand, these pharmacies also have a more or less important effect by giving advice. When someone just presents his prescription and fetches the medicine, then there is no real reason why the gross margin should be high. In German one even uses the word "Apothekerpreise" to say that something costs too much!

When the pharmacist has a few employees and pays decent salaries, then his profit will be lower and it will give work to people. This argument often is abused to justify too many public servants in a too fat state.

The average citizen does not profit from that, because administration in all but a few cases is not really productive. So people living in a slim and efficient state usually are happier.

This short description proves that the text of Mr.Malkoutzis is not well balanced.

It also proves that reforms can not be implemented by third party, even when they have correct theories.

When there is no deeper insight in the local population and no initiative locally arising then the sad verdict is clear: such reforms are doomed to fail!