-

Is the Greek green transition running out of power?

Is the Greek green transition running out of power?

-

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

-

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

-

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

-

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

-

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

It's the hope that kills you

The ski resort of Ischgl in Austria has been linked with thousands of infections around Europe. More than 6,000 infections from 45 countries including Germany, the UK and the US were tied with the outbreak in early March.

Austrian prosecutors are investigating the claims that delays in shutting down the resort and the mass departure of holidaymakers in an uncontrolled fashion led to the high number of infections.

The interconnectedness of western and central Europe during the months of February and March due to winter skiing holidays and school half terms has been recognised as one of the factors contributing to the rapid spread of the virus in the continent at the start of 2020.

In contrast, during this early period of the pandemic, Greece found itself in an advantageous position because its hospitality sectors were in hibernation during the winter months, preparing to awaken for the reopening in spring.

Greece does not host any major conferences or trade fairs during those months. The main event that would have attracted travellers from abroad, the Delphi Economic Forum, which was scheduled for the end-February/early-March was cancelled as the virus was ripping through neighbouring Italy.

The first leg of the Champions League game between Atalanta, the team from Bergamo, and Valencia had to be played 35 miles down the road at San Siro in Milan, when 40,000 Atalanta fans took the trip. Doctors have linked this game on February 19 with the outbreak in Bergamo and the spread in Spain.

Again, in a stroke of luck, the poor state of Greek football means its teams rarely feature in the knock-out stages of European competition.

Greece announced its first confirmed Covid-19 case on February 26, a woman that returned from a trip to Milan in Italy. Italy at the time was already reporting close to 250 per day and already had 21 coronavirus-linked deaths.

Greece rode a wave of good fortune and followed the rest of Europe as countries started to shut down under the pressure of mounting cases, strain on hospitals and rising deaths.

Without having felt any true pressure from cases and casualties, by March 10 and with just 89 confirmed cases of Covid-19 the authorities closed all schools and within one week the country had gone into a general and strict lockdown.

The first wave should have made clear to the Greek authorities the benefits of being in relative isolation, allowing them to contain the virus. They should have appreciated how the favourable timing made their task to protect Greeks easier.

The lockdown, which lasted roughly 40 days and was lifted in line with other European countries at the beginning of May, affected the economy dearly with GDP dropping by more than 15 pct. Naturally, as travel came to a standstill across the globe tourism became an immediate casualty.

Rash reopening

The start of Greece’s reopening process was when the first signs of complacency from the authorities became evident.

Having secured a good outcome on the health front, the government quickly shifted its attention to opening up the economy as quickly as possible, with the main objective of ensuring the country was ready to be fully operational for the tourism season.

Initially, there were very bullish, albeit entirely disconnected from reality, estimates in May that Greece would be able to secure between 8 and 10 billion euros of the 18 billion in travel receipts it received in 2019 and that Greece would be open for business from June.

Reality hit home quickly as it took time for air connections to be reinstated. Airports opened gradually, while other countries that Greece was expecting visitors from took longer to allow travel abroad. In general, Europe was trying to find its footing after hunkering down for close to two months.

At the same time, key markets for Greece like the US and Russia were experiencing their own waves of the pandemic and travel from those markets came to a halt.

Gradually, the expectations were tempered. The signals from early bookings were not encouraging, and Greece’s goal was adjusted. The new target was for total travel intakes of 5 billion euros for the season.

Greece did not demand a negative PCR test from visitors from any country that it had opened its borders to. Instead it deployed an algorithm, the details of which have not been made public yet. The way it reportedly worked was that it allocated a percentage of sample testing per flight based on certain risk criteria per country of origin.

Even for travellers from the UK, who were accepted two weeks later than the rest of Europeans, there was some element of red tape via a Passenger Locator Form. The tests were random and even those selected to test did not have to quarantine in their room until their results were available. It is believed that the quarantine requirement until the test was cleared was dropped after pressure from the tour operators.

Greece went on an aggressive promotion campaign, led by the Prime Minister holding a press conference against the idyllic backdrop of a Santorini sunset. He welcomed prospective travellers to Greece, advertising it as a safe destination.

Safe start

Greece was indeed safe when the tourism season launched.

The country never really had to contend with shocking coronavirus figures. At the peak of the first wave, the daily cases were barely moving above 100. By the end of April, when the lockdown was about to be lifted, Greece had short of 2,600 total cases.

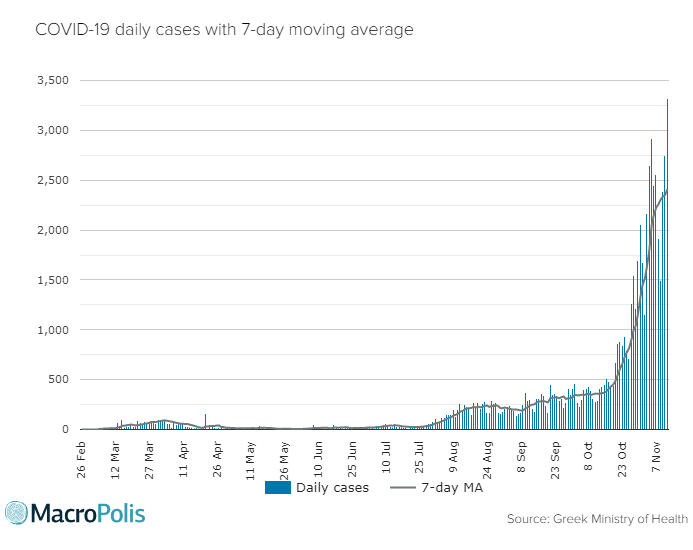

The 7-day moving average of daily cases on June 1 was five and by the start of July it was 17. In mid-July, when the tourism season was declared fully open, the daily cases moving average was just 41.

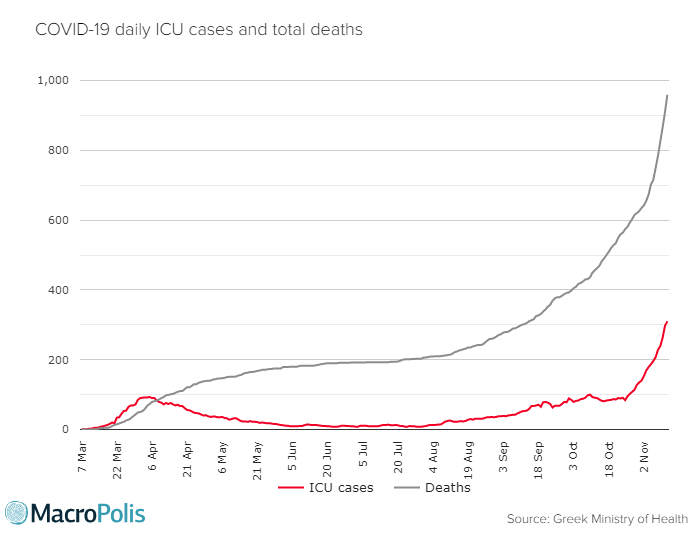

The total number of deaths by June 1 was just 179 and the figure plateaued just over 190 for most of July. On June 6, Greece had less than 10 people requiring ICU treatment and the figure was around 10 for most of July.

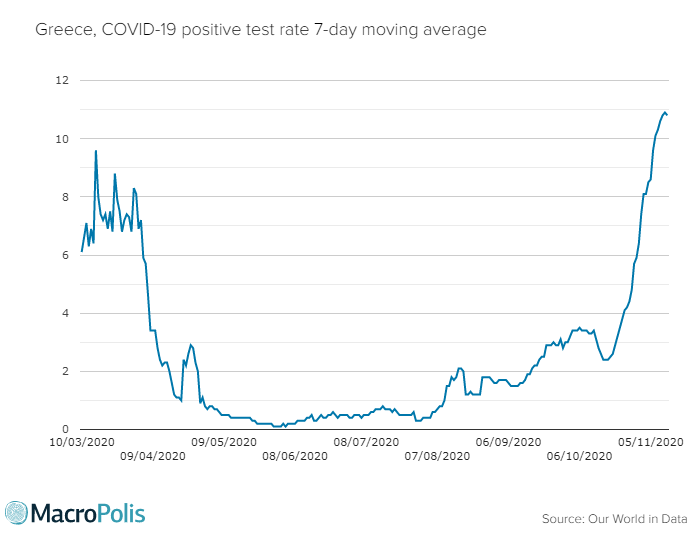

Greece never really adopted a wide testing policy to root out any signs of the virus in the community. During May, 3,442 tests were conducted on average daily, with the average rising to 4,692 tests per day in June as visitors were gradually tested at entry points.

In May and June, the average positive rate per test was just 0.46 pct in May and even lower at 0.34 pct in June.

These were truly enviable numbers. All the factors that could work in Greece’s favour did, and the country seemed Covid-free. Greece took a massive gamble by throwing open its doors again, seeking maximum economic benefits.

Data from Bank of Greece show that up to August, 4.8 million tourists visited the country. Although the figure pales in comparison to the 21.8 million that had visited during the same period last year, it is close to 50 pct of the Greek population.

Arrivals from within the EU were 3.1 million and 1.7 million came from outside the EU. Although down by nearly 73 pct, more than 725,000 Germans still came to Greece, another 528,000 visitors came from the UK.

The signs of the risks involved in welcoming tourists started appearing in the tests carried out at the entry points, where the positivity rate in July averaged 4.15 pct. Although the method of averages does not capture the entire picture and testing methodology, on a like for like basis on positive rates, visitors were 10 more times likely to carry the virus.

The perfect viral storm started forming in Greece as the holiday season for Greeks also began. Locals left the cities for islands and coastal resorts where they would meet and mingle with travellers from abroad.

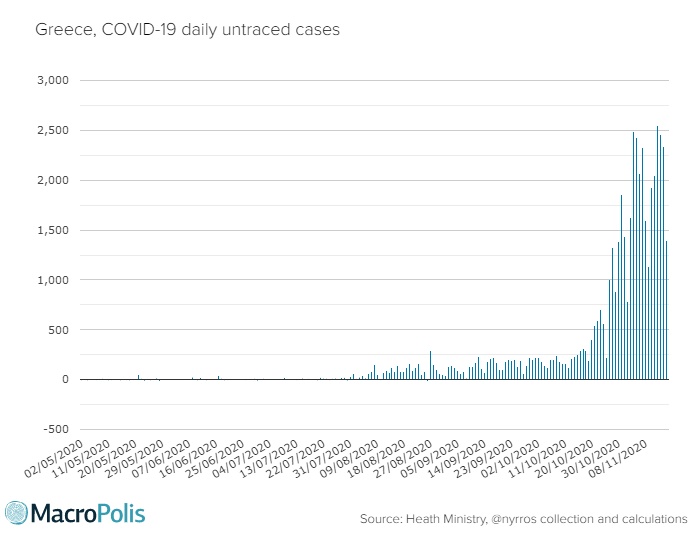

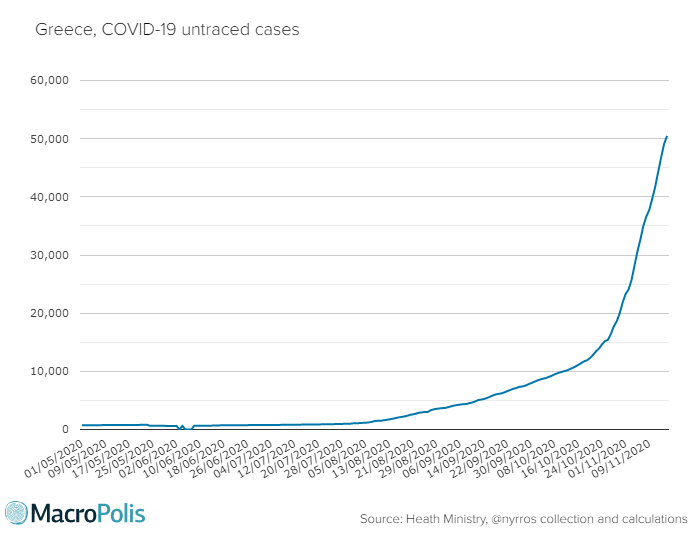

A good indication that Greece had the Covid-19 situation control before tourism began was the low daily number of untraced cases, i.e. those that could not be traced back to a specific positive case or were related to travelling.

Up to the end of June, there were fewer than 750 untraced cases and just a handful were reported daily. That picture changed quickly in July, and by mid-August untraced cases had exceeded 2,000. By the end of August, the untraced cases had reached close to 3,700.

Control lost

The authorities started losing the control they had on the situation, with the picture deteriorating on the northern border, where most visitors from the Balkans cross into Greece by car.

With the health data in the Balkans getting worse, the authorities introduced the requirement of negative tests for entry. At the same time, the picture domestically started looking grim as little islands started going into local lockdowns to curb the pandemic spread and foreigners started testing positive after they returned home from Greece.

These developments essentially brought the tourism season to an abrupt stop, just as the second wave of the pandemic started picking up momentum in certain countries in Europe.

The tourists left and Greeks went back to their homes and jobs in the cities. Testing started to pick up the consequences of the developments during the summer, spurred by the government’s decisions to reopen the borders with a relaxed approach.

Hundreds of thousands of Athenians were crammed daily in the metro to go to work at rush hour, schools opened at full capacity, university students went back to their classes, worshippers went to churches, where they shared in holy communion, and social life continued as normal, meeting, dining and mingling in line with the message of the authorities that Greece had beaten the pandemic and was now open for business.

It was not long before all this started to be reflected in the number of cases. August started with a 7-day moving average of 67 cases, but closed with 213. September also had a steady rise to more than 300.

The situation started to have an impact on the numbers of Covid-19 patients being treated in ICUs. This went from 8 at the end of July to 67 by mid-September.

Greece went from reporting no deaths at all in June to 8-10 daily by the end of September. Total deaths climbed up to 391 by the end of September.

It was evident that something potentially dangerous was simmering beneath the surface as testing picked up and the positivity rates jumped to an average of 2.5 pct in August when they would barely go over 0.5 pct before the season opened.

Positive test rates reached 4.4 pct by the end of September - a nine times rise within just three months.

By the end of September untraced cases had climbed to 8,000, from 831 when the season fully opened mid-July, a ten times increase.

It should be noted that Greek authorities have been inconsistent in providing full Covid-19 data, and that the task of creating a full picture regarding the numbers has been taken up by a few individuals, such as Twitter user @nyrros.

Second wave

In the absence of any strict measures to break the circuit of transmission and with authorities reluctant to introduce restrictions that would hamper economic activity, Greece would need another dose of luck to contain the damage.

When the authorities realised that they would need to signal a significant change in the public’s attitude, the self-congratulatory and relaxed approach of the preceding months was abandoned. Naturally, their message did not resonate, as Greeks continued their daily lives within the allowed boundaries.

The authorities did not manage to convince anyone across the age spectrum. Young people did what young people usually do and older people continued their routines: Cafes, bars, restaurants, demonstrations, churches and packed metro trains.

The government has spent most of November introducing restrictions pretty much every other day, before being forced into another general lockdown as of November 7.

Deaths have risen by nearly six times to 1,100 since mid-July. The health system is under severe pressure with ICU admissions at 392, from just 35 at the end of August.

The economy is expected to tank in the last quarter, even if some of the festive season shopping spree is salvaged. Just five weeks ago, the Finance Ministry’s forecast was for a recession of 8.2 pct and a strong recovery of 7.5 pct. Now, these estimates are out of the window as the recession is seen in double digits and next year’s recovery at a more moderate 4.5 pct.

The government will have to fork out another 3.3 billion euros of economic support to cushion the blow, on top of the close to 16 billion euros in actual fiscal measures that have been adopted so far.

Events and numbers indicated that all this huge economic, social and personal loss is the outcome of the government’s decision to take a risk with the way it decided to open the tourism season. Based on the latest available data and estimates, travel receipts will barely exceed 3 billion euros, suggesting that any benefits were minimal.

During a speech in Parliament in mid-June, Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis said the government was “turning the summer into the season of sowing so the autumn becomes the spring of hope.”

They are right when they say, “it’s the hope that kills you.”

*You can follow Yiannis on Twitter: @YiannisMouzakis

1 Comment(s)

-

Posted by:

Yes, the Greek development has been unfortunate, particularly when comparing it to the stellar performance in the spring, but one also has to see it in the European context. Greece has a 7-day-incidence (cumulative infections of the last 7 days per 100,000 people) of just under 150. While that is high, it's about the same level as that of Germany and both, Germany and Greece, are among Europe's top performers as regards Corona. Just think that the 7-day-incidence in Austria, also a rather good performer in the spring, is 527 (!) as of today. Austrians would be exhilarated to have Greece's level!