-

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

-

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

-

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

-

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

-

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

-

15% Uncertainty: Greece, Europe and the tariff shockwave

15% Uncertainty: Greece, Europe and the tariff shockwave

The allocation of labor resources in Greece and the EU-27

Greece is trying to boost growth in real GDP and to transform the country into a more efficient and effective generator of economic wellbeing for its population. New reform efforts have been proposed by the Pissarides Report (2020), and the EU Recovery Fund – once it is operational – will make available to Greece some 32 billion euros in support of investments and modernization of the productive apparatus.

One of the key aspects of achieving a well-functioning economy relates to the allocation of labor resources. If you want bigger real GDP, where and how do you encourage employment growth to take place? Putting this question another way: would you try to employ most people in the private or in the public sector?

In most countries, the public sector is seen in a supportive role of the economy. This role is (very) important in many aspects, but the public sector tends not to be the focus of real GDP growth. In most cases, the private sector is the true engine of such growth. Indeed, if private sector firms do not constantly find ways to increase their productivity per employed person, then they will most likely go out of business and make place for newer and more nimble companies. The Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter called this process of economic innovation “creative destruction.”[1] The public sector never goes out of business, no matter how inefficient it is. If it runs short of money, it will either default on part of the debt, or raise taxes, or a combination of these two options.

Having said this, what we can also observe is that as per-capita income in countries increases, the demand for public services (e.g. transport infrastructure, education, health) and public goods tends to expand. Thus, government involvement in any economy tends to increase as countries become wealthier. Such involvement reflects government functions taking up a larger share of GDP over time. We can see this expansion in classic areas such as demographics (e.g. pension policies) and the provision of social benefits to various constituencies. With the current Covid-19 pandemic the important task of government support for the public health system is reshaping the rationale for such involvement.

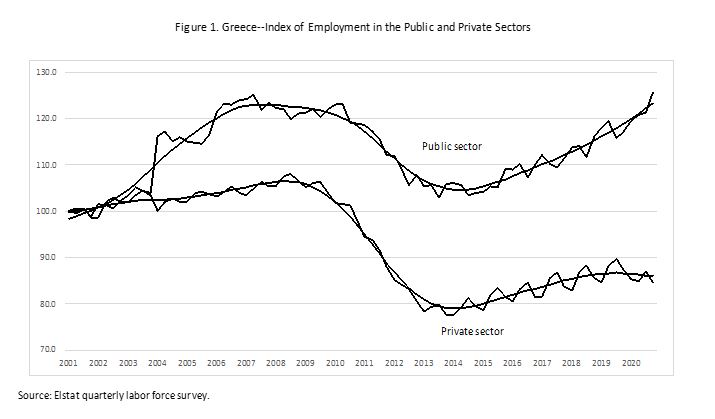

Let us now take a closer look at the allocation of labour ressources in Greece. As a first entry into the enquiry about labor resource allocation between the public and the private sector, we have collected data published by Elstat in the quarterly labor market survey since 2001. We then plotted an index (2001-Q1=100) for employment in the public and private sectors. Figure 1 shows the results (both the original time series and a smoothed underlying trend line that takes out the quarterly and seasonal ups and downs).

- The index lines allow us to see at once by how much employment has grown or declined in the public and private sectors since early 2001. From figure 1, it emerges that public employment was booming prior to the euro crisis in Greece in 2009. In 2004 (Summer Olympics in Athens) and 2006 (local elections) employment jumped. These leaps were never unwound afterwards. Then, between 2009-2013 employment was dramatically reduced in the heat of the Greek crisis. But since 2014, employment in the public sector has resumed its growth path. It has accelerated again in 2020, perhaps related to the Covid-19 pandemic. At end-2020, the public sector employed 26 percent more people than in early 2001, even though real GDP in 2020 was 10 percent smaller than in 2001.[2]

- By contrast, labour allocation in the private sector has seen quite a different trajectory. Employment increased prior to the Greek crisis during the boom years 2001-2008. But this increase was moderate when compared to the public sector trend. Then, as the crisis unfolded and demand weakened substantially, the private sector adjusted employment in order to keep up productivity per person employed. This led to a cumulative decline in employment by some 20 percent through 2013-2014. In 2013, real GDP was 7 percent smaller than in 2001. Alas, after 2014, employment started to grow again, albeit at a moderate rate. However in 2020, it leveled off again and began to slowly decline.

This difference in behavior by the public and private sectors in Greece is striking and requires an explanation. The economy weakened, but public sector hiring increased; whereas private sector hiring reflected the fortunes of real GDP as companies adjusted to keep productivity growth intact.

If it is true that the private sector is the engine of growth in a modern economy, and the public sector plays a supportive role, why would Greece want to allocate more and more of its labor force to the public sector and see its private sector shrink, in relative terms? We will publish more research about this inquiry in future blogs. But a preliminary answer suggests that allocating more and more employees to the public sector (at the expense of the private sector) is not a growth enhancing policy, nor does it lead to maximizing productivity in the Greek economy.

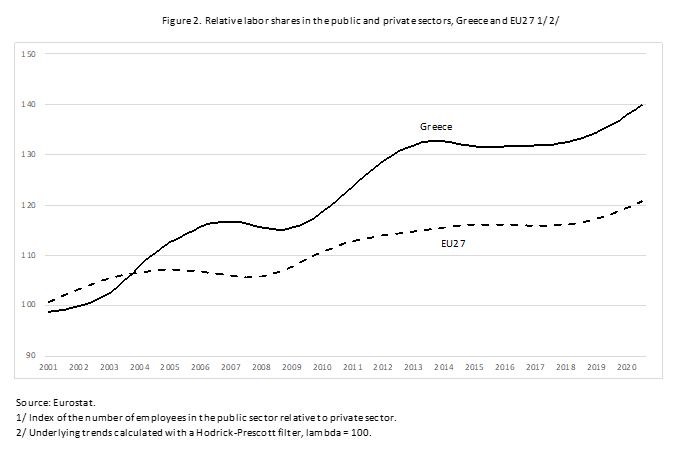

Let us now put the Greek development in a comparative context. For that matter we use Eurostat data to see if the same process also applies to other countries of the European Union. Eurostat publishes a quarterly labor force survey of all member states, so we can compare the results for Greece with that of the EU-27. Our findings are highlighted in Figure 2.

Figure 2 shows the underlying trend lines only, to avoid the up-and-down stories that make interpreting high-frequency data difficult. We plot relative growth in public versus private sector employment in the economy of Greece (top solid line) and the EU-27 (bottom dashed line). Thus each line takes employment in the public and private sector as in Figure 1. Then we compute the ratio between the two employment lines. The results are telling:

- What we see is that Greek public sector hiring has outstripped private sector hiring, as was already established in Figure 1. In relative terms, since 2001 the public sector has become 40 percent bigger than the private sector (regarding the hiring of employees). Put otherwise, in relative terms, labor resources have predominantly been absorbed in the public sector.

- Interestingly, this process is also seen in the EU-27, but the numbers are smaller. The EU-27 public sector has hired 20 percent more labor relative to the private sector.

- Closer inspection of the data reveals other instructive details. In Greece, private sector employment has dropped. In the EU-27 as a whole, private sector employment has increased. This is consistent with real GDP developments: in Greece real GDP is smaller; in the EU-27 real GDP is bigger today than it was in 2001.

- The data also remain consistent with the conclusion that in Greece, the public sector is growing relatively faster than the internal relations between public and private employment for the EU-27 as a whole.

Each country has its own history of labour market policies. Greek society can chose to develop its economy through the public sector, rather than the private sector. But such a sovereign policy choice triggers consequences. One effect is that within such a model average growth will be smaller than in countries that emphasize the private sector to lead growth dynamics. Another outcome concerns per-capita income which tends to grow more slowly than in partner countries that favor a private sector led growth trajectory. There is no obligation for EU partner countries to make up this difference in income through transfers.

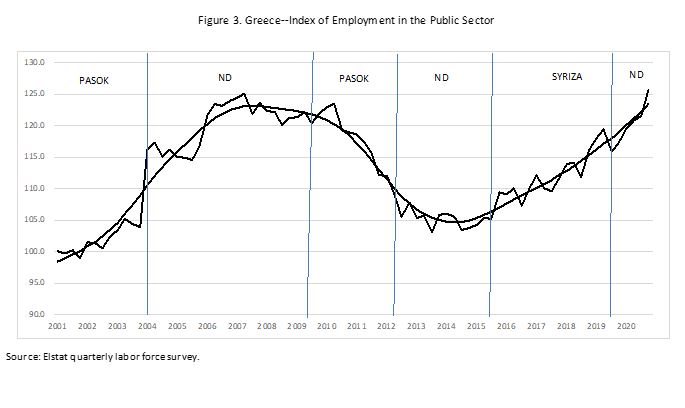

The key decision maker in each country driving this process is the political system. This leads us to Figure 3 (above). Figure 3 shows which Greek governments increased or decreased public sector employment between 2001 and 2020.

Most people believe that conservative governments are cautious with public finances and employment. But this belief is not backed-up by the reality on the ground. Figure 3 shows that ND increased employment considerably under PM Karamanlis (2004-2009) and again under PM Mitsotakis (in office since July 2019). The Karamanlis public sector employment boom is all the more striking as this took place on top of a large increase during the last few quarters of PM Simitis’ PASOK government while preparing for the 2004 Summer Olympics in Athens.

We argue that this boom was the result of extraordinary circumstances. Once the Games were finished the increase should have been scaled back. But it was not. Politics had the upper hand. The biggest decline in government employment took place during the PASOK period 2009-2012. This downward trend was yet again reversed during the subsequent ND government of PM Samaras. Coming into office in January 2015, SYRIZA subsequently stuck to its election promise to hire more public sector employees. After winning the elections in mid-2019, ND further accelerated this employment trend. Some, but not all of this recent increase is due to hiring in the health sector to assist with the Covid-19 pandemic.

Put otherwise, in a key policy area, namely public sector employment, there was continuity across the political aisle despite major ideological differences between SYRIZA and ND. This is at variance with the usual political sentiment that conservative governments favor economic development through the private sector. Both ND and Syriza appear to have more in common than meets the eye when it comes to the allocation of labour resource in Greece.

*Bob Traa is a macroeconomist and author of "The Macroeconomy of Greece: Odysseus' Plan for the Long Journey Back to Debt Sustainability" published in 2020. Jens Bastian is senior policy advisor at ELIAMEP.

[1] See Joseph Schumpeter, 1942, Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy.

[2] 2020 real GDP has been depressed by Covid-19, so the end-point observation is unusually unfortunate. But even if the pandemic had not occurred, we estimate that the size of real GDP in 2020 would still have been slightly smaller than in 2001. Hence we draw the conclusion that growth in public employment in Greece is structural, not cyclical.

1 Comment(s)

-

Posted by:

Timely & valuable analysis. Results as expected. Inevitably. Some indications that the situation may change with the use of EUNGF. Since the pandemics necessarily lead to great state presence part of the answer is to run public sector companies as efficiently (or close to) as private ones.