-

Is the Greek green transition running out of power?

Is the Greek green transition running out of power?

-

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

-

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

-

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

-

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

-

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

Is Greece on track to decouple from fossil gas?

As Europe was recovering from a major energy crisis that severely tested member states’ national economies, Greece, along with other European countries, experienced unprecedented natural disasters in the summer of 2023, directly linked to the intensifying climate crisis. The common denominator of both crises is fossil fuel dependence.

Whereas nearly all European countries have committed to phasing out lignite and coal in electricity production, most of them before 2030, the future of fossil gas remains uncertain. In fact, it constitutes a key issue in the national energy and climate plan, which is due to be completed in June 2024. In order to explore the prospects of gas use in Greece, it is necessary to evaluate the existing energy planning in relation to both the country’s recent performance and the structural changes in European energy and climate policy that have taken place over the past two years, shaping a new landscape.

Russian gas

The "root" of the energy crisis lies in the EU's dependence on Russian gas; member states were vulnerable to the rise in gas supply prices that Russia was trying to impose. By 2021, when the crisis started, Greece was on par with the European average, importing approximately 40% of gas intended for domestic use from Russia. However, the crisis radically reversed this situation.

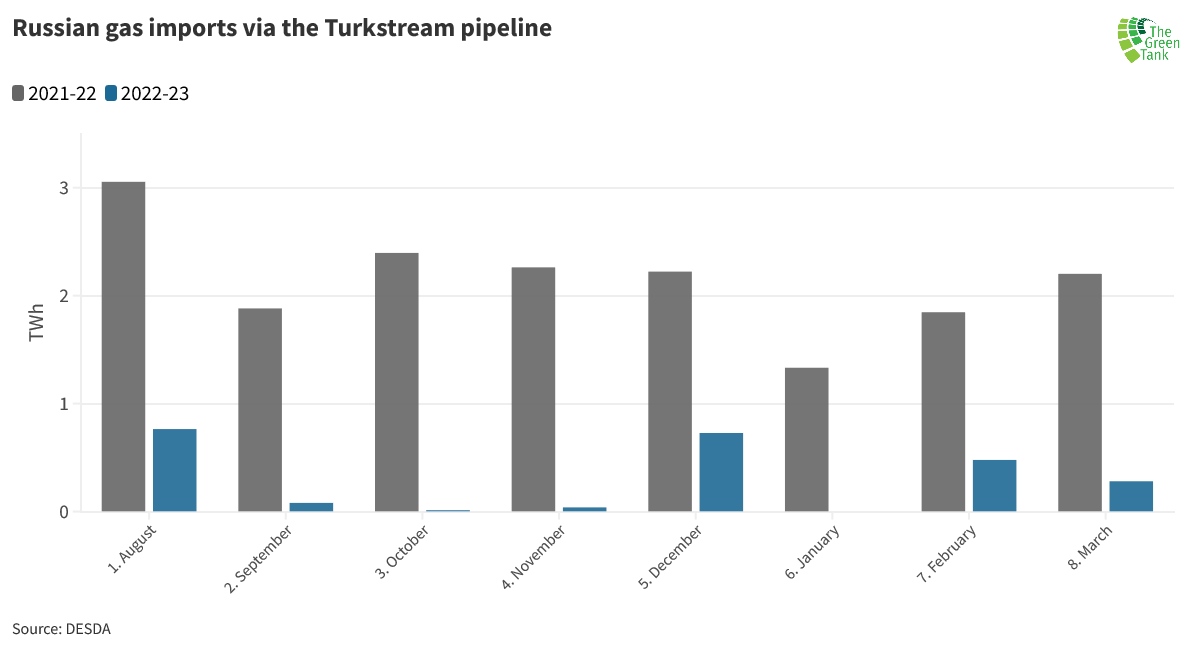

Even though it seemed unfeasible when Russia invaded Ukraine on 24 February 2022, Greece succeeded to nearly eliminate the Russian gas used to meet domestic needs that was imported via the Turkstream pipeline. It is worth noting that during the eight-month period of reduction of total gas consumption decided by the European Union for all its member states (August 2022-March 2023), Greece cut Russian gas pipeline imports by 86.2% compared to the same period of the previous year. In particular, in each month of autumn 2022 the relative reduction exceeded 95% compared to the same month of the previous year, while, for the first time in January 2023, Russian gas imports were literally null (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Russian gas imports from the Turksteam pipeline through the Sidirokastro gateway in each month of the eight-month reduction period (August 2022 - March 2023) compared to the same month of the previous year.

This performance undoubtedly shielded the country against the energy crisis, while contributing to the geopolitical weakening of Russia. Nonetheless, it also led to the collapse of the narrative that had flourished during the crisis and which saw Greece forced to build new liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminals in order to reduce its dependence on Russia. In contrast, Greece succeeded to meet its domestic gas needs with just the existing Revithoussa LNG terminal at its disposal and minimal imports of Russian gas via the Turkstream pipeline.

Total gas consumption

The measures taken -admittedly late- by the European Union to safeguard itself from the energy crisis were not limited to Russian gas. The REPowerEU plan, which was first published just 12 days after the start of the war and then completed in May 2022, indeed made it a priority for Europe to completely decouple from Russian gas by 2027; nonetheless, it also aimed to prevent a geographical shift of this dependence to other countries.

It is no coincidence that, even in the short term, in view of the previous winter, the EU-27 chose to impose on its member states a reduction in the total consumption of fossil gas -not just Russian- of at least 15% over the period August 2022-March 2023, as compared to the average of the previous five years regarding the same eight-month period.

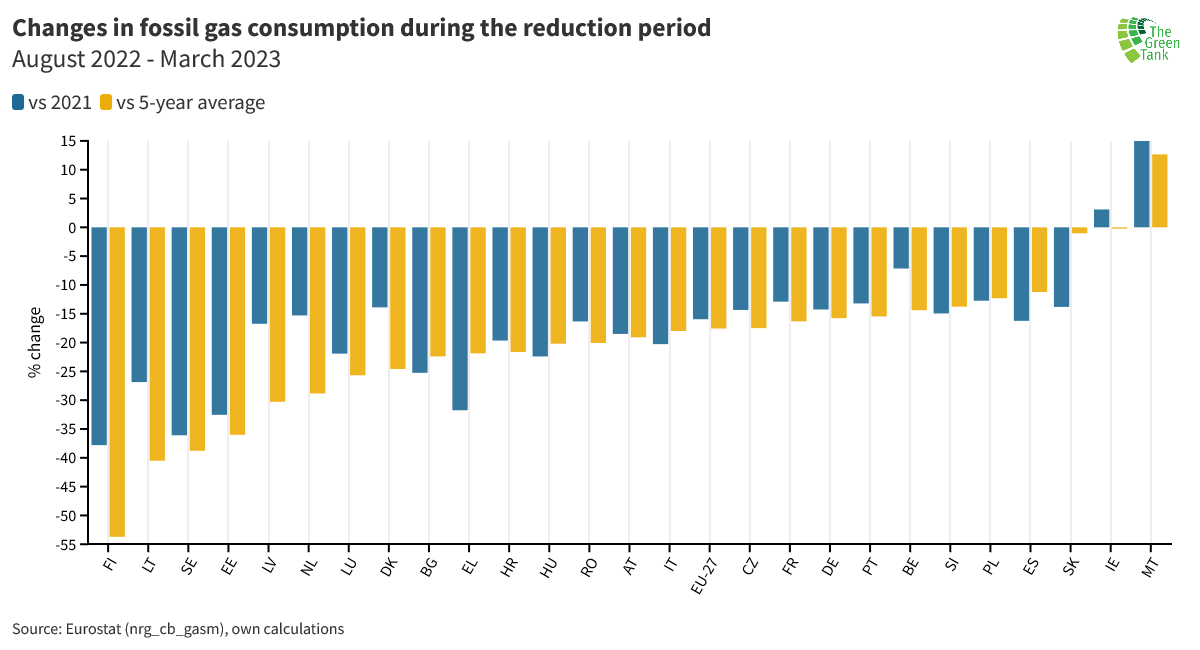

Greece managed to achieve this target effortlessly, reducing its total gas consumption by 21.9% in the eight-month reduction period compared to the five-year average. It ranked 10th among the EU-27, outperforming both the European average and countries such as Germany, Austria and Italy (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Changes in total gas consumption in the 27 EU-27 Member States over the reduction period (August 2022-March 2023) compared to the five-year average and the previous year for the same eight-month period.

This feat is indeed noteworthy, considering that the Greek government -under pressure from several large gas consumers in the country- sought and was eventually granted an exemption to this obligation. More specifically, in the case of Greece, the eight months of the previous year alone -rather than the five-year average- would be used as a baseline to calculate the 15% reduction; this provided the country with a "cushion", namely, approximately 5.7 TWh of additional gas consumption during the reduction period. As it turns out, Greece did not need this exemption. Compared to the eight months of the previous year, it reduced its consumption by 31.8%, more than double its contractual obligation; in fact, Greece’s performance put her in fourth place among EU-27 states, behind only Finland, Sweden and Estonia.

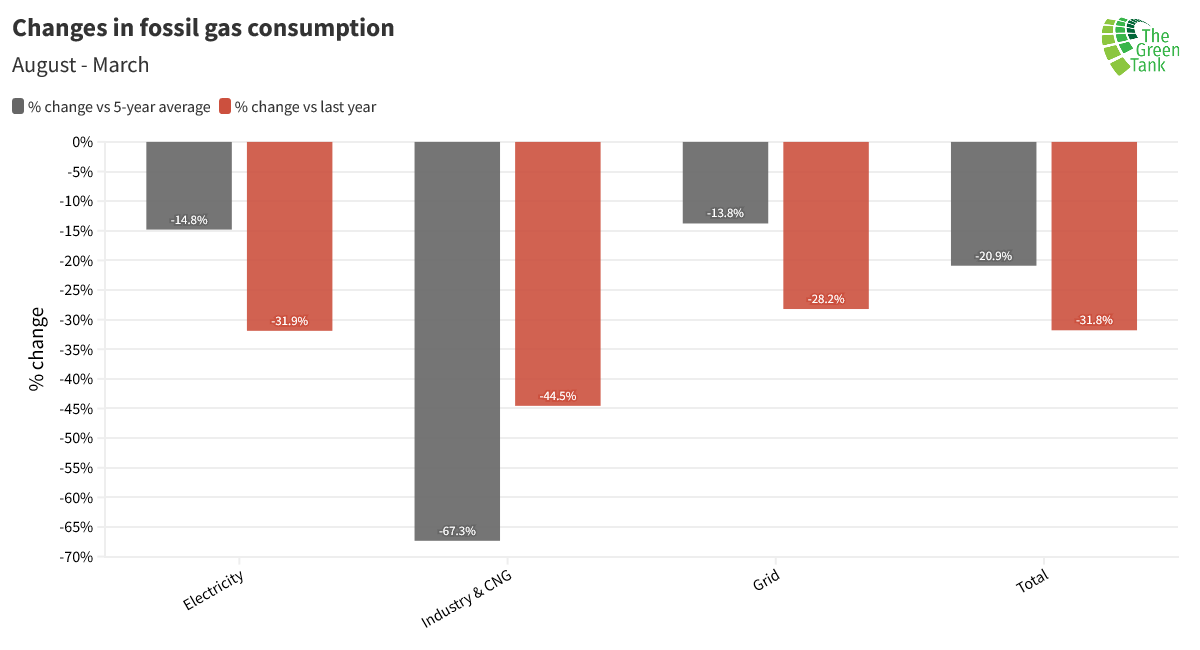

The data of the Hellenic Gas Transmission System Operator SA (DESFA) offer a more in-depth look at the "architecture" of this gas use reduction in Greece. These indicate that end-use sector that contributed most in absolute terms was electricity production, where consumption in the eight months August 2022-March 2023 compared to the five-year average decreased by 4.02 TWh, followed by industry (-3.37 TWh) and distribution networks (-1. 3 TWh). However, in percentage terms, the largest decrease was noted in industry which, under pressure from high prices, reduced its gas use to just 1.6 TWh over the eight-month period of August 2022-March 2023; this corresponds to a 67.3% decrease compared to the five-year average (Figure 3), which highlights industry’s potential to substitute gas with other fuels.

Figure 3: Changes in fossil gas consumption in end-use sectors; comparison of the reduction period (August 2022 - March 2023) with the five-year average and the previous year for the same eight-month period.

Despite a significant fall in gas supply prices in 2023 compared to the peak of the energy crisis, the decline in gas use persisted throughout the year. Thus, 2023 closed with a total domestic consumption of 50.9 TWh, 10.1% lower than in 2022 and 27.2% lower than in 2021, the year that the energy crisis begun. Gas use in industry recovered partially, reaching 5.2 TWh for 2023, 2.4 TWh higher than the nadir of 2022, but still significantly lower than the five-year average (7.2 TWh). This increase in industry was far outweighed by the consumption cuts in distribution networks (approximately 1 TWh, or -8.1%), and more significantly, electricity production (7.1 TWh or -17.1%), thus leading to a cumulative reduction in fossil gas consumption by 5.7 TWh between 2022 and 2023.

The role of gas in electricity production

The primary end-user of fossil gas in Greece is by far the electricity production sector, with an average share of 68% over the last five years. Therefore, in order to understand the prospects of gas use in Greece as a whole, it is necessary to examine its role to date, especially in this sector.

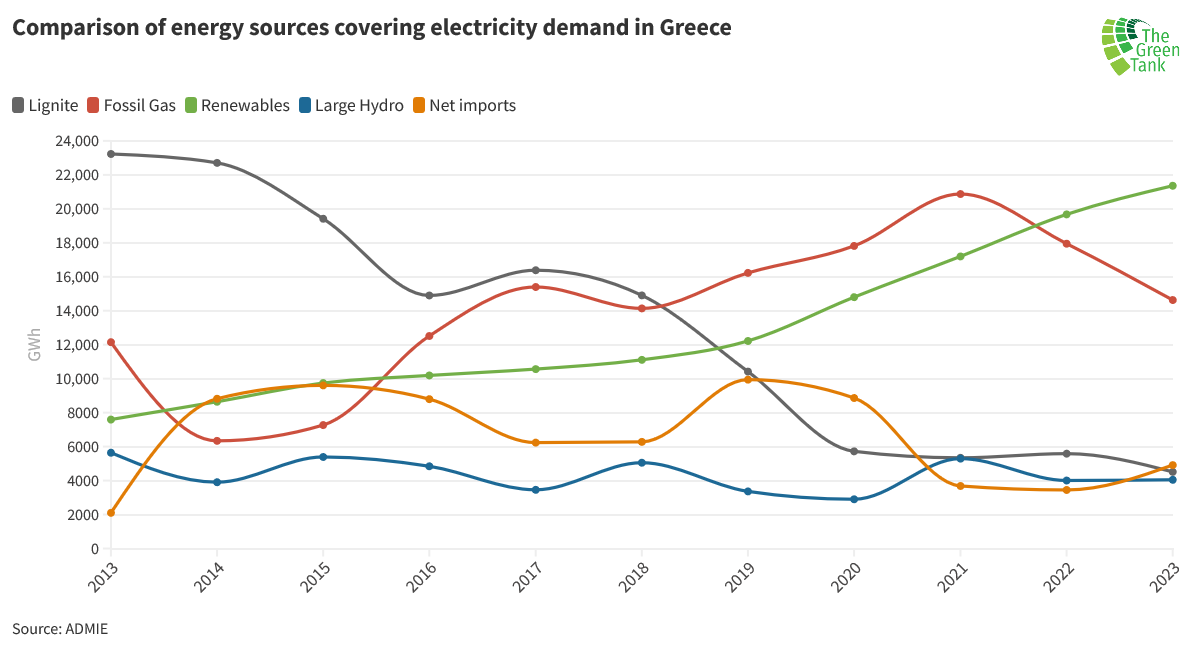

As illustrated in Figure 4, fossil gas displaced lignite from the lead in the Greek electricity production mix in 2019, when phasing out lignite was accelerated due to the escalating prices of carbon dioxide emission allowances on the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS); the latter, in turn, contributed decisively to the political decision to phase out lignite use by 2028 at the latest. Gas use in electricity production remained on an upward course in the following years, reaching a remarkable peak (20.9 TWh) in 2021. The crisis brought a complete reversal of this trend. Thus, gas has been plummeting over the past two years, with its contribution in 2023 (14.6 TWh) approaching 2018 levels. In 2022, for the first time, Renewable Energy Sources (RES) (mainly wind and photovoltaics) took the lead in the electricity production mix; moreover, with a remarkable 21.4 TWh in 2023, for the first time RES-based electricity production exceeded that from gas and lignite combined.

Another first in 2023 was the fact that RES, together with large hydro, covered more than half of electricity demand (51.4%), while their cumulative share of domestically produced electricity in the interconnected grid amounted to 57%. In addition, 2023 was marked by a historic low for lignite, whose share in meeting demand fell below 10% (9.1%) for the first time; moreover, the country operated for 28 (non-consecutive) days without any lignite plant in operation. Equally notable was the continued decline in total consumption, which reached a 10-year low in 2023.

Figure 4: The evolution of the electricity production mix in the interconnected grid over the past decade.

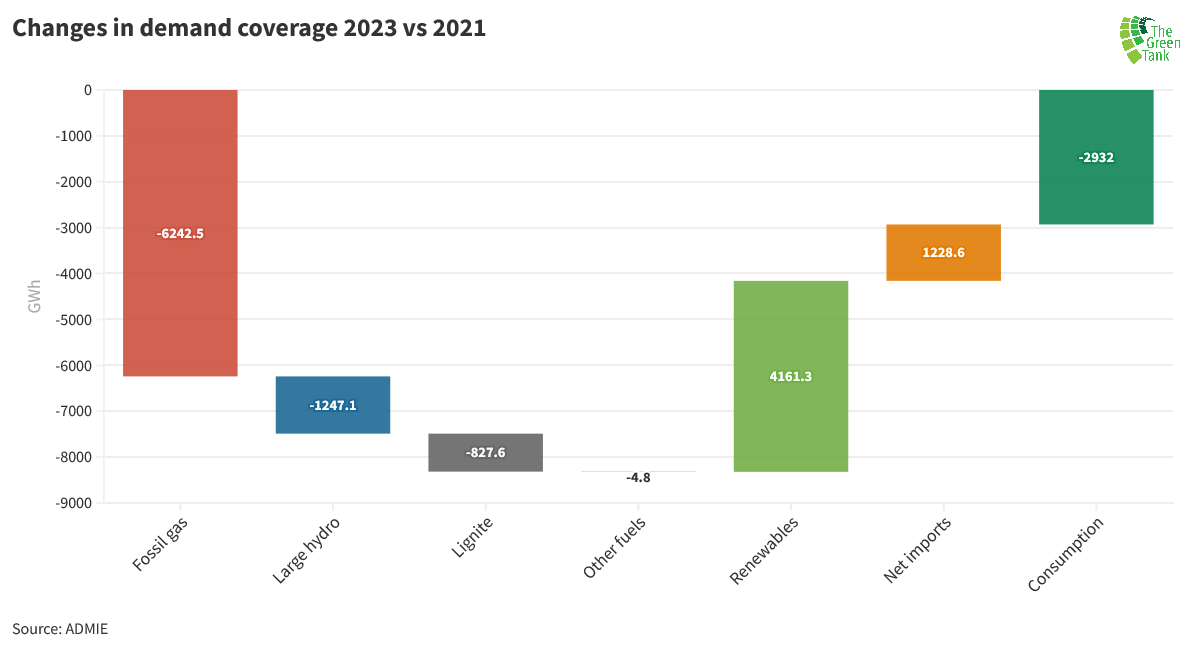

Figure 5, below, delineates how the large change in Greece's energy mix over the past two years was achieved. As illustrated, the large reduction in gas contribution between 2021 and 2023 (-6. 24 TWh) and the smaller decline in production from large hydropower (-1.25 TWh) and lignite (-0.83 TWh) were compensated primarily by the growth in RES (+4.16TWh) and the reduction in total electricity consumption (-2.93 TWh), and secondarily by the increase in net electricity imports (+1.23 TWh)[1].

Figure 5: Changes between 2021 and 2023 in meeting electricity demand.

These findings indicate that reducing gas use without a simultaneous increase in lignite is entirely feasible if Greece sticks to the path of RES development, while limiting overall electricity consumption to the extent that this is possible, given the efforts to gradually electrify other sectors of the economy. Moreover, it is important to note that the radical decline of gas use in electricity production was sustained in 2023, even after gas supply prices partially recovered; therefore, the changes that have taken place over the last two years are systemic in nature, rather than circumstantial.

Contradictions in Greece’s energy planning

Despite its many positive features, certain elements related to fossil gas that are included in the draft of the revised National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP) contrast the progress made over the last two years, jeopardizing the long-term sustainability of the country's energy model.

LNG terminals

Firstly, the plans regarding at least two new LNG terminals -one in Alexandroupolis and another in Agioi Theodoroi in Corinthia- are particularly problematic, whereas plans regarding additional LNG terminals have not been definitively abandoned. DESFA's data, however, show that LNG imports to Greece in 2022, which were entirely carried out through the existing terminal at Revithoussa, amounted to 38 TWh. Given that this amount exceeds even NECP’s rather unambitious goal regarding domestic consumption in 2030 (36.9 TWh), the new LNG terminals are not essential for the country's energy security. The second reason invoked in the NECP to justify the construction of these terminals is Greece's contribution to regional security, namely, its role in safeguarding neighboring countries’ gas supply and independence from Russian gas. In fact, recently, at the Davos Economic Forum, the Greek Prime Minister linked the new LNG terminals to meeting needs outside the EU-27, and in particular Ukraine. This statement expands on the old national energy policy doctrine, of Greece becoming a transit hub for fossil gas through new gas pipelines and LNG terminals.

Nonetheless, and with regard to the EU-27 Member States, the REPowerEU plan foresees a massive reduction in total gas consumption in Europe by 2030 (-52% compared to 2019 levels). reduction in total gas consumption in Europe in 2030 (-52% compared to 2019 levels). Given that before the war the target for reducing overall gas use was nearly half (-29%) under the 'fit for 55' package, this new policy signals the EU's -unuttered but certain- abandonment of the ‘dogma’ that gas should constitute a 'transitional fuel'. Moreover, both the crisis and the recent energy policy decisions in Europe have illustrated that safeguarding countries' energy security and supporting their economies is best achieved via a decisive shift to renewables, combined with increased energy efficiency and energy savings. There is no reason why this conclusion would not apply in the case of Ukraine. Therefore, there is a serious risk that the planned new LNG infrastructure will end up being stranded assets. This is a genuine concern, considering the large reduction of LNG imports to Greece recorded in 2023 (-22.5% compared to 2022), which, combined with the reduction of gas exports to Bulgaria via the Sidirokastro gateway over the same period (-45.5%), ascertains a regional decline in LNG demand. Moreover, under pressure to immediately address the ever-worsening climate crisis, US President Biden recently implemented a temporary suspension of the issuance of pending and new permits for US LNG exports -the primary source of imported LNG in Greece. This decision amplifies the risk of the new LNG terminals serving no purpose.

New fossil gas-fired electricity production plants

Specifically, with regard to the electricity production sector, the NECP includes plans for two new gas-fired plants to be added to the existing fleet, increasing total net capacity from 6 GW in late 2023 to 7.7 GW by 2030. At the same time, despite the higher capacity, the NECP provides that gas-fired electricity production will drop from 14.6 TWh in 2023 to 11.7 TWh in 2030. With such a limited use of gas-fired plants in 2030, their financial sustainability cannot be ensured through their participation in the daily electricity market alone.

Therefore, two scenarios appear to emerge. In the first scenario, gas-fired plants will contribute to the energy mix at a far higher extent than that foreseen in the NECP. In this case, the share of renewables in 2030 will drop below 82% (i.e the NECP target) and the corresponding emissions from the electricity sector will exceed the approximately 4 million tons of CO2 estimated in the NECP; this, in turn, will compromise the NECP’s fundamental climate target of reducing emissions from all sectors of the economy by 54% in 2030 compared to 1990 levels. Moreover, in Greece, renewables have long had lower electricity production costs than both lignite and gas; therefore, a possible displacement of RES in favor of fossil gas will raise the cost of electricity for consumers, thus burdening households and businesses financially, and damaging the competitiveness of the Greek economy.

In the second scenario, the NECP targets for both gas and RES shares in 2030 will be met. However, in order to be economically sustainable, especially the new gas plants currently under construction, will need additional financial support, which will most likely come through a capacity remuneration mechanism (CRM). Regardless of the details of such a mechanism, the additional costs will burden consumers; thus, this scenario too will result in higher electricity costs and related negative consequences.

New gas infrastructure for building heating - The case of the lignite areas

Contradictions also emerge in the planning regarding the use of gas in building heating. Unlike other Member States, gas use in this sector is relatively limited in Greece. However, at a time when Europe is turning to RES to meet its heating needs, planning in Greece aims to increase gas use, extending the distribution network to 34 cities nationwide, despite the International Energy Agency’s recommendations to reconsider the feasibility of these plans. Moreover, this planning appears to dismiss the recent introduction of a new European Emissions Trading System (ETS) specifically for buildings and road transport (ETS2), which, from 2027 onwards, shall place an additional fee on the use of fossil fuels in these two sectors.

The case of Greece's lignite regions clearly illustrates the impasse that citizens will reach if local authorities and central government insist on employing gas to heat households. With the use of lignite steadily declining, an alternative solution was sought out to address the heating needs of citizens in the lignite areas; for decades, these needs had been met by lignite plants, mainly through district heating systems. Thus, following the decision to phase out lignite, in 2020, with gas supply prices at the TTF ranging between 4.1 και 16.4 €/ΜWh and the notion of ETS2 in Europe yet obscure, Greece’s central government, in cooperation with representatives of local authorities, formulated a plan; the latter was a complex solution -consisting of many individual projects- that will rely entirely on fossil gas to meet the heating needs of the five largest lignite cities (Kozani, Ptolemaida, Florina, Amyndeo and Megalopolis). Based on the calls issued to date for all sub-projects, the total construction cost of this solution -including the projects to transfer gas to Western Macedonia from Trikala in Imathia- is expected to exceed €400 million. Beyond construction costs, however, it is paramount to consider the increased cost of operating the planned system; the latter will either be borne entirely by the citizens of the lignite regions, or part of it will come from state aid, thus burdening all Greek taxpayers. Suffice it to say that -using conservative forecasts for the evolution of fossil gas supply prices- by implementing this solution, the cost of district heating for the citizens of Greece’s largest lignite city (Kozani), currently at 55 €/MWth is expected to soar to 103 €/MWth.

Exploitation of domestic hydrocarbon deposits

Despite the need to accelerate the energy transition having been acknowledged, the official national energy planning, as reflected in the NECP, insists on the exploration and exploitation of domestic hydrocarbon deposits with an emphasis on fossil gas. In April 2022, the Prime Minister, himself, declared 6 such projects throughout Greece a national priority.

Here lies yet another major contradiction in Greek energy policy. Firstly, according to scientists, the exploitation of new hydrocarbon deposits will torpedo the effort to contain the global temperature rise to 1.5°C compared to pre-industrial levels. Furthermore, this track is in complete discord with the government’s acknowledgement of the accelerating dire effects of the climate crisis, especially after the devastating fires and floods that Greece experienced in 2023. Finally, the government’s attempted link between Russia's war in Ukraine and the added economic value of exploiting domestic hydrocarbon deposits is now obsolete, as gas supply prices on international markets have dropped significantly.

Do alternatives exist?

The past two years have emphatically demonstrated Greece’s great potential to reduce gas consumption in all three end-use sectors. It is precisely this performance, together with the broader EU strategy to reduce gas consumption by 2030 as reflected via REPowerEU, that should guide the design of the national gas consumption policy -not company decisions regarding investments in new fossil gas infrastructure. The latter were, after all, taken before Russia's invasion of Ukraine and REPowerEU, which has fast-tracked Europe's decoupling from fossil gas.

It is therefore necessary to revise the plans regarding new gas-fired power plants, new LNG terminals and the gas network extensions intended for 34 cities nationwide. Particularly with regard to new power plants, all decisions should be preceded by a Resource Adequacy Assessment, exploring the increased penetration of renewables combined with increased storage capacity[2] as an alternative to new gas plants. In any case, the 7.7 GW of total gas plant capacity in 2030 will not be economically viable; therefore, the NECP should feature a retirement schedule for older gas plants along the lines of the retirement schedule regarding lignite plants already included in the NECP.

The final NECP to be submitted by June 2024 should reflect the fact that Greece is already on track to achieve an electricity production mix based entirely on RES by 2035. With such a target Greece will join countries such as Austria, Denmark, Lithuania, Luxembourg and Portugal, all of which have already committed to employing 100% RES in electricity production by 2030; furthermore, together, the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, France, Luxembourg, Austria and Switzerland have recently committed to achieving a fossil-fuel-free electricity mix by 2035.

With regard to the heating needs of citizens in Greece’s lignite areas, planning should be radically modified to focus on long-term sustainable renewables-based solutions[3], combined with energy upgrades and heat pumps. These are perfectly feasible solutions, as countries such as the Netherlands are already implementing them, despite being much more dependent on fossil gas for heating buildings than Greece. Furthermore, these solutions are fully eligible to receive funding from the European Just Transition Fund, unlike fossil gas-based heating systems, which are excluded.

In particular with regard to Kozani, during the interim period following the withdrawal of the lignite units connected to the city’s district heating system and prior to the completion of the construction of a final heating solution, the city could employ electric boilers at low construction costs; similar boilers have been providing heating in the city of Ptolemaida for three consecutive winters.

Finally, Greece's definitive disengagement from the old ‘dogma’ of exploiting domestic hydrocarbon deposits should be reflected in the National Climate Law; this constitutes a minimum prerequisite for the alignment of national climate policy with the escalating, bleak climate reality that we are called upon to face in the coming years.

*Nikos Mantzaris is a senior policy analyst and partner at The Green Tank

This work was carried out with support of the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in Athens as part of a climate journalism project.

[1]Greece is a net importer of electricity in the sense that the quantities of electricity imported are larger than those exported. Net imports in 2023 met 9.9% of demand in the interconnected grid, while their average share over the last decade is 12.1%. Imports mainly come from Bulgaria, North Macedonia and Albania, while Greece mainly exports to Italy.

[2]Electricity storage is necessary to support high penetration of variable RES (mainly wind and PV), in order to balance increased production with electricity demand. There are currently several technologies used to store excess electricity, the most mature being pumped hydro energy storage (PHES) and batteries. In addition, electricity from RES can be stored in the form of heat in various storage media such as molten salts (thermal storage) or used to produce green hydrogen through electrolysis. The latter is expected to play a key role in decarbonizing the more challenging sectors of the economy, such as industry and heavy vehicle transport. The draft NECP also reflects the need to develop storage infrastructure, as it already foresees 2.2 GW of PHES (the current capacity being 0.7 GW) and 3.1 GW of batteries, as well as 300 MW of electrolysis systems to be employed for green hydrogen production by 2030.

[3]Already, most of the district heating in the city of Amyndeo is met via the two new 30 MW biomass combustion units, which were constructed due to the retirement of the Amyndeo lignite plant in 2021; until then, the latter channeled part of the heat produced from lignite combustion to cover the heating needs of the city. In addition, solutions based on various RES technologies will be implemented to replace district heating from lignite in other transition regions such as the Šalek Valley in Slovenia.