-

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

-

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

-

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

-

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

-

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

-

15% Uncertainty: Greece, Europe and the tariff shockwave

15% Uncertainty: Greece, Europe and the tariff shockwave

UnLuCky for some: Another painful lesson from the euro crisis

No matter what overall opinion you have of the Greeks, you really ought to hand it to us for tolerance. Over the last year and a half one of the three key players in Greece’s crisis management team has repeatedly and openly admitted that the prescription for addressing the country’s predicament was wrong.

First, the International Monetary Fund’s chief economist Olivier Blanchard, a highly respected figure, confessed in early 2013 that the fiscal multipliers used in the design of the Greek programme were off by a wide margin. As a result, the austerity being applied was inflicting three times the damage on the economy and employment than had been thought initially. When this was combined with the fact that the programme was designed not based on what funds Greece needed for a smooth transition period but on how much “generosity” was available from the eurozone, it led to the country losing a quarter of its economy on the troika’s watch.

A few months after Blanchard’s admission, the IMF issued its evaluation of Greece’s first programme. This opened a new can of worms. Without pulling any punches, the report threw all the dirty water – as Olli Rehn put it - on the European Commission, highlighting that it did not have a clue about how to handle the crisis. The IMF argued in the report that debt should have been restructured up front. Instead, Greece’s first programme worked as a holding operation that allowed defences to be built to stop the eurozone suffering from contagion. By protecting and giving a way out to fragile French and German banks, the burden was shifted from irresponsible lenders to eurozone nations and taxpayers.

Now, an IMF paper published this week delivers the final blow to what the troika defined as the foundation of Greece’s programme - the “correction of external imbalances and restoration of competitiveness.” It says:

“The large current account deficits in Greece, Ireland, Portugal, and Spain have shrunk drastically or turned into surpluses largely because imports and potential growth have slowed down drastically relative to pre-crisis trends.”

“Their NFLs (net foreign liabilities) remain very high (implying higher net income payments), and the progress with external rebalancing has come at the expense of internal balance, notably sharply higher unemployment rates.”

Design flaws

If you are a euro crisis season ticket holder you must have heard regularly that countries built imbalances during the first decade of the euro and they now have to go through the painful process of restoring balance, reducing current account deficits and regaining the competitiveness lost through wage inflation in excess of productivity gains.

The IMF paper provides a refresher for everyone concerned as it reminds those who created the euro that they were promoting it on the basis that balance of payments constraints would disappear at the national level and that capital flows would lead to a convergence of income levels within the euro area. Current account deficits, real effective exchange rate appreciations and higher inflation between periphery and core would be healthy by-products, they claimed.

The euro’s nemesis would lie right within this sales pitch: When the crisis stuck and there was a classic case of a sudden stop of capital flows, just as in any emerging markets crisis in the past, the oversights during the years of bliss came to the fore and there was a realization that weak counties were exposed because they had a currency they did not control. The euro’s problems suddenly became national rather than common.

Until that moment, the deterioration of Greece’s current account was considered part of the desired effect of euro convergence. When things started to unravel, though, critics started to line up to punish the Greeks. To make matters worse, when the architects of the single currency came to fix what had gone wrong they produced another mistaken diagnosis. As a result, 18 percent of Greece’s economy evaporated between 2011 and 2013, while 15 percentage points were added to the unemployment rate.

After deciding that current accounts do matter after all, one of the troika’s main objectives became to improve Greece’s competitiveness and close the current account gap, which stood at 15 percent of GDP at the start of the crisis. The term Unit Labour Cost became sacred. The sure way to achieve the desired effect is by depressing domestic demand via pressure on disposable income, reducing imports, improving the trade balance. Since there is no one to finance your excess imports you keep turning the screw until it is your exports that finance your imports and your trade is balanced.

Disposable incomes were depressed in a number of ways at the start of the Greek programme. Tax increases and higher unemployment gave rise to informal wage reductions and more flexible forms of employment until the troika decided as part of the second programme to speed up the process further by reducing the minimum wage by over 20 percent. This led to all the collective wage agreements in various sectors that were based on the minimum wage also being renegotiated downwards.

The programme

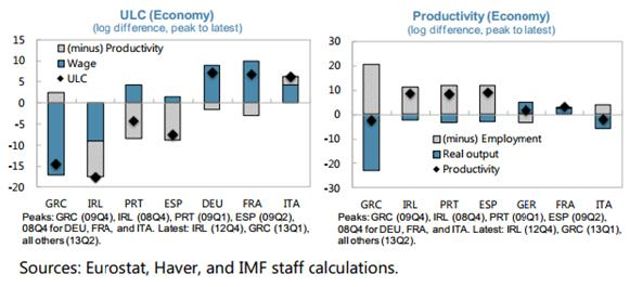

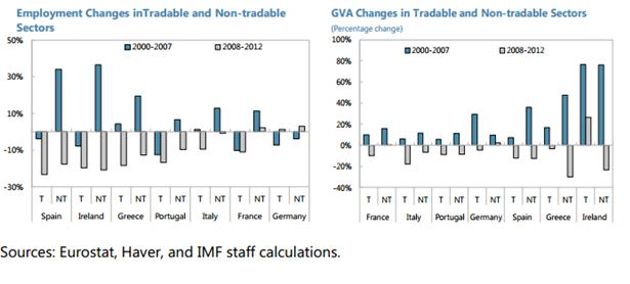

The latest IMF paper highlights the shortcomings in the design of the Greek programme. An adjustment process that aims to correct such an imbalance and improve competitiveness should have two main components. Firstly, domestic prices have to fall in comparison to foreign prices and then profitability in the tradable sectors has to rise relative to the profitability of non-tradable goods. This intends to attract more people to export-oriented economic activity and import demand via what you are selling abroad.

The aim is to secure the relative price adjustments by reducing production cost, including wages, and the reallocation of production to tradable sectors by improving their profitability.

However, the IMF paper points out, the real exchange rate appreciation and loss of competitiveness between 2000 and 2009 has come from the appreciation of the euro itself and the majority of the increase in Unit Labour Costs (their measure of competitiveness) came in the non-traded sectors and this is why exports in the same period did not get affected. As such, the attempt to depress the entire economy with the aim of improving competitiveness is beyond incompetent. It is criminal because it hits the economy with a sledgehammer and aggravates what caused the Greek crisis in the first place - the Greek political elite’s fiscal binge and debt addiction, which led to the country’s bankruptcy. As the economy goes into freefall, revenues drop and expenses for a social safety net are required - a combination which has a self-defeating nature in meeting fiscal targets, combined with the denominator effect in terms of debt to GDP ratio.

Programme objectives were pushed beyond reach because even improving productivity was a non-starter since producing more output per resource became impossible when more output was lost than resources who managed to keep their employment.

Even if you want to take the “Protestant” view on Greece’s programme, which envisages pain being needed so there can be salvation, you will not find much comfort because the economic depression did not lead to any gains. As was previously highlighted by the OECD, the loss of income through lower wages became just higher profit margins for exporters, who in the absence of a functioning banking system to finance working capital were starved for liquidity and simple cash flow operations.

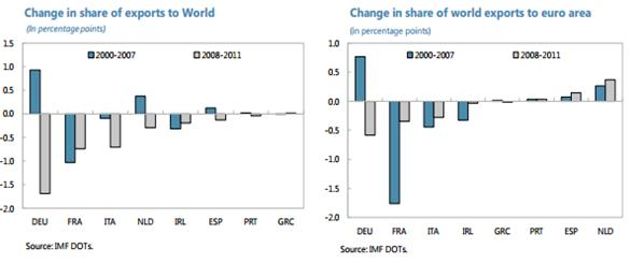

Market shares do not offer any consolation as Greece’s market share in world trade declined and the internal devaluation did not even assist intra-euro trade.

The reallocation of labour to tradable sectors never occurred. It has actually dropped and the gross value added of the tradable sector in Greece has marginally declined.

Greece’s exports have barely moved in the last four years because trade that specialises in markets that are growing slowly outside the euro area and depressed demand within the single currency zone, where everyone decided to implement austerity policies at the same time, meant there was a high probability that the “scorched earth” policy might not have the desired effect. Somehow, this was overlooked.

It does not end there. Greece cannot say it is looking ahead to a brighter future with certainty despite enduring all that pain and economic devastation for essentially no “competitiveness gain.”

Since the improvement in the current account came purely from the economic depression and the drastic drop in demand, it is highly probable that when the economic cycle turns there is a risk that the current account will start deteriorating. This means going through the adjustment again or, if you don’t trust the remedies offered, putting up with subdued demand and high unemployment for a while.

At the same time, since your net foreign liability position has not improved at all this might act as a deterrent to inflows of capital, affecting the prospects for investment and growth.

On more than one occasion, and on a number of fronts, Greece has been the victim of the wrong diagnosis, wrong prescription, zero benefit and at risk of a perma-slump. Taking all this into consideration, you have to ask yourself: Even if you were the most tolerant nation on the planet, would you allow the same people to carry on dictating policy?

2 Comment(s)

-

Posted by:

This is a selective and biased presentation of the latest IMF research report on adjustment in the deficit countries of the Euro area periphery. As the report mentions on p. 18: "The export performance of Greece was significantly weaker than predicted by external demand and relative price adjustments. This could reflect [...] structural and non-price impediments". Surely the fact that Greece did not implement the structural reforms called for under both the first and second rescue packages had something to do with lagging exports in Greece? Although competitiveness as measured by relative prices (as in the IMF report) has improved significantly, broader measures such as the World Bank's Doing Business Report or the World Economic Forum's Global Competitiveness Report still rank Greece at the bottom of Euro area countries and even below some sub-Saharan African countries. This low ranking reflects the cost of bureaucracy, high and constantly changing taxation, chaotic licensing procedures, regulatory impediments to competition, time-consuming contract enforcement, rigid labor legislation, etc. Surely these impediments go a long way toward explaining why Greece is the only Euro area periphery country where exports have not yet recovered to their pre-crisis level.

-

Posted by:

Thank you for the comment although I find it unfair to call it selective and biased when it has touched upon the majority of the findings in the IMF paper within the boundaries of a blog post.

Equally I do not disagree with any other issues that you raise, I actually think they highlight the failure of the approach that solely by reducing the unit labour cost, an approach which I understand is closer the Commission’s heart than the IMF’s, would be the necessary condition to improve Greece’s place in the global trade scene. It is evident from the IMF paper that was a superficial approach to the issue.

The troika has proven repeatedly that it has turned a blind eye when it comes to addressing rigidities in the Greek economy. If the same strictness that was applied in fiscal targets was applied in the implementation of true structural reforms the program would have had much greater chances of success, exports performance included

-