-

Is the Greek green transition running out of power?

Is the Greek green transition running out of power?

-

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

-

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

-

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

-

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

-

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

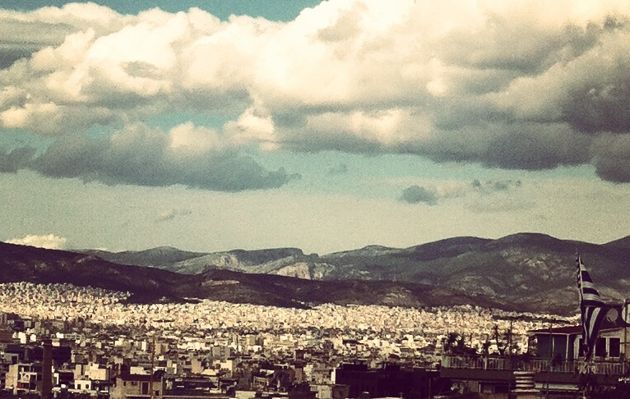

Greece: The gathering storm

As the dust settles from Greece’s negotiations with its lenders and the arduous work of implementing their agreement begins, it is becoming increasingly evident that the next four months will be an extremely testing experience for everyone concerned.

There are several reasons to begin bracing for the turbulence ahead. One is that the new Greek government is still on a steep learning curve and is liable to make slip-ups. It’s apparent determination not to keep its own counsel and the tendency for its ministers to speak into any and all microphones put in front of them is compounding the problems it faces.

On Wednesday, three ministers gave three different messages about what the government plans to do with VAT. On the same day, Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis suggested that Greece would have trouble paying its 1.6-billion-euro loan repayment to the International Monetary Fund, while Economy Minister Giorgos Stathakis insisted that the government did not have any funding problems. A day later, State Minister Alekos Flambouraris indicated that the government might indeed be unable to pay the IMF in full and could ask for part of the repayment to be delayed.

This picture of confusion is in contrast to the persistently blunt message being broadcast from German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schaeuble. After rubbing salt into the Greek side’s wounds after the Eurogroup deal on February 20, when he wondered aloud how Varoufakis would explain the agreement in Athens, the German politician has maintained extreme pressure on the SYRIZA–Independent Greeks coalition. Ahead of the vote in the German Parliament, he insisted that no money would be released to Greece unless it completes the review and made it clear that failure to live up to the terms would lead to the agreement being declared null and void.

Schaeuble also accused Varoufakis of “straining the solidarity of European partners”. It was just one of several personal jibes from the German minister towards his Greek counterpart. These comments carry dual significance. Firstly, because Schaeuble sets the tone for the rest of the Eurogroup, as underlined by the fact that Eurogroup chief Jeroen Dijsselbloem, European Commissioner Pierre Moscovici and IMF managing director Christine Lagarde negotiated on February 20 with Varoufakis in one room and Schaeuble in another to thrash out a deal before the meeting of the eurozone finance ministers began.

Schaeuble’s insistence is also significant because it gives an idea of how fraught the process of implementing the agreed reforms and then having them reviewed by lenders is going to be for Greece over the next four months. Since the beginning of the bailout process in 2010, Germany has turned towards the IMF to act as its enforcer on the ground, believing that the European Central Bank and the European Commission do not have the expertise or resolve to ensure that terms are being met. The way that Schaeuble appeared to try to sideline the Commission’s efforts to find a compromise with the Greek government before February 20 suggests that these reservations still exist in Berlin. This means Schaeuble and German Chancellor Angela Merkel are likely to turn to the IMF again over the next few months to ensure that they are getting their money’s worth from the coalition in Athens. This is where the next concern about how the process will evolve over the next few months arises.

While the Commission, the Eurogroup and the ECB signed off relatively easily on the reform package proposed by the Greek government on February 23, the IMF adopted a more dissenting line. In her response to the proposals, Lagarde recognised the Greek proposals as a “valid starting point” but raised a number of concerns about elements that appeared to be missing or were not covered in enough detail. These included reforms for pensions, VAT, opening up closed sectors, privatisations and the labour market – all of which are political hot potatoes in Greece.

“As you know, we consider such commitments and undertakings to be critical for Greece’s ability to meet the basic objectives of its Fund-supported program, which is why these are the areas subject to most of the structural benchmarks agreed with the Fund,” added Lagarde, indicating that regardless of what the new government has agreed with the Eurogroup, the IMF will still be looking for Greece to deliver in areas where the previous coalition failed.

Lagarde’s response seems to leave only limited room for flexibility and suggests that the government will be asked to delve into a lot of areas that it would prefer to leave untouched at this stage given the already fragile state of unity within SYRIZA. However, the way the Fund, driven by rules and procedures, works means that Athens will have to meet specific structural benchmarks before it can qualify for further loans. This means the current coalition cannot escape the nightmarish reviews that its predecessor approach with a mixture of dread and panic if it expects to receive the IMF’s 3.5 billion euros from the total of 7.2 billion in pending instalments.

Schaeuble, meanwhile, has insisted that Greece will not get a cent of the remaining part of the tranches if it does not complete the review. This ties Athens down to the incredibly testing process of working with lenders to draft and pass legislation so the review can be wrapped up. At the same time, it will have to ensure that it does not alienate creditors by adopting measures that run counter to their goals. There has already been some friction over privatisation, payment plans for overdue taxes and plans for the settlement of non-performing loans. Also, the various sides have not yet sat down to discuss the complex and extremely technical issue of the fiscal gap and any relevant measures that need to be taken.

All this forms an extremely challenging environment for the new government, which has no experience of this process and will also have to launch, in parallel, discussions about what kind of package can be agreed to carry Greece on from July, when the current four-month extension ends. This suggests the next four months will be the most definitive period of the Greek crisis.

Follow Nick on Twitter: @NickMalkoutzis

*This article appeared in last Friday's e-newsletter, which is available to all subscribers either by logging on or via our free mobile apps.

6 Comment(s)

-

Posted by:

Dean: "For Greece at this point (and after a 40% internal devaluation) to accept an additional 50% for a new currency is beyond stupid".

Don't worry Dean, there are plenty of stupid people inside and outside Greece pushing for this.

How people fail to understand that going to Drachma you do not start with a clean slate but you carry your debts (in EUR) is beyond me.

How will politicians manage to weather the transition to a mickey mouse currency when they have been unable to do their job in good times is something that defies logic but those luminaries conveniently choose to ignore.-

Posted by:

Switching to the Drachma certainly involves carrying your debts unless they are repudiated. Any not repudiated would indeed remain in EUR unless they are unilaterally redenominated (those under Greek law could be switched with ease). Do not believe the Goldman Sachs self-serving view that introducing Drachmas is impossible. It would be painful, maybe more so than continuing with the EUR, but it could be done, perhaps to benefit in the longer term.

-

Posted by:

Matador, agreed. But when you are in a negotiation everything is on the table.

Whether you mean or not only you know.

-

-

Posted by:

No doubt that the future does not look bright.

However, Mr. Malkoutzis once more has fallen into the temptation to show Schäuble as the major enemy of Greece. I suggest to see Schäuble as a hidden friend of Greece, because he and Varoufakis both know that only Grexit can reestablish independence of Greece.-

Posted by:

Inside the euro Greece will be intentionally asphyxiated more and more by its creditors: none of them is going to help Greece. I really do not understand how Varoufakis can (rightly) define "waterboarding" the treatment Greece has received in the past years, and at the same time hope this treatment can stop or really change now, with a new SYRIZA government — which Germany & Co hate and want destabilize, before it can become a model for other countries.

I hope they know all this very well and are only buying time to be prepared with a new currency in 4 months. Without at least the threat of a Grexit, nothing of its programme can be achieved by the greek government in the next bargaining.

But, beyond that, Greece needs its own currency and central bank to recover. Once regained monetary sovereignty, it can default, get external devaluation and restart its internal production, and it can run expansionary policies without raising imports. Inside the euro expansionary policies are forbidden not only by the treaties, but by the lack of exchange rate: any internal demand increase would lead to a current account imbalance. -

Posted by:

Let me state out the obvious.

Grexit is acceptable but it's not for free. For 1 Trillion euro it could arranged.

For Greece at this point (and after a 40% internal devaluation) to accept an additional 50% for a new currency is beyond stupid.

Any defaults will be within the eurozone and this part is not negotiable.

-