-

Is the Greek green transition running out of power?

Is the Greek green transition running out of power?

-

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

-

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

-

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

-

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

-

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

It remains a mystery

![Photo by Can Esenbel [www.mundanepleasure.com] Photo by Can Esenbel [www.mundanepleasure.com]](resources/toolip/img-thumb/2013/10/10/blue_esenbel_800_1010-large.jpg)

The Wall Street Journal leaked this week the minutes of an International Monetary Fund board meeting in May, 2010, just a few days before Greece signed its first bailout. The extracts reveal that there was serious concern among about a third of the country representatives, who raised serious objections about the Greek programme.

“The risks of the programme are immense… As it stands, the programme risks substituting private for official financing. In other and starker words, it may be seen not as a rescue of Greece, which will have to undergo a wrenching adjustment, but as a bailout of Greece’s private debt holders, mainly European financial institutions,” said Brazil’s IMF executive director Nogueira Batista.

Once again, damning revelations about the design of the Greek bailout were mostly met with nonchalance. There was silence from Berlin and Brussels on the IMF leaks. One analysis in a Greek newspaper suggested that the sceptics at the IMF were only speaking up because they had the luxury of hiding behind the cloak provided by the Fund’s preferred creditor status. The reaction to the WSJ’s report simply confirms how distorted the debate about Greece’s programme has been since the early days of the crisis.

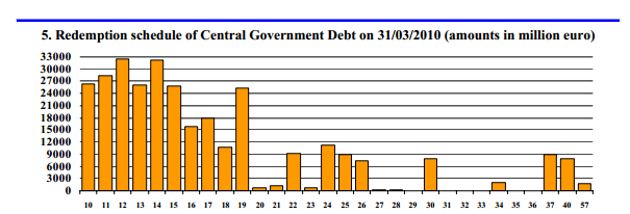

Leaving the eurozone complexities and contagion risks aside, it is difficult to comprehend on what grounds, anyone would attempt to discredit the solution of an upfront debt restructuring for Greece back in the spring of 2010 when the schedule below is taken into account.

Greece managed to tap the markets for the last time on March 11, 2010 with a 5-billion 10-year issue and a coupon of 6.25 percent. From that point on it became apparent that funding at sustainable rates was no longer available and the country was essentially facing bankruptcy.

In the three years ahead, Greece would have to face maturities worth 86 billion euros. The number was a mammoth 168 billion for maturities up to 2015 and by 2019 an impossible 237 billion euros, which translates into three quarters of its outstanding debt at the time.

At the same time, to service this debt Greece needed 13.2 billion in 2010 which was the equivalent of circa 6 percent of the country’s GDP.

Again, leaving aside any wider eurozone, banking stability and ring fencing intentions, can anyone seriously argue that a country which was broke, with no one willing to lend it, that had over half of its debt maturing in the next five years and needed close to 15 percent of its revenues to meet interest payments on this debt did not perfectly fit the profile of a candidate for debt relief?

From a financing perspective, even assuming the same deeply recessionary fiscal consolidation policy mix that was followed, Greece needed 86 billion euros to refinance its debt in the 2010-2012 period, 25.5 billion for the primary deficit and approximately 40 billion euros in interest payments (on the assumption that interest levels in 2012 were the same as in 2011).

This means that from a total of circa 152 billion euros of total financing needs, 126 billion was to refinance and service the debt of an effectively bankrupt state.

It is truly ironic that the idea of debt restructuring in 2010, which is still dismissed by many, was welcomed in 2011. Of course, this was only after private creditors were given a way out via the EU-IMF program and the ECB had engaged in its Securities Markets Program (SMP), leading to a significantly reduced pool of debt being eligible for restructuring and the risk now shifted to European taxpayers, in case something went terribly wrong with Greece.

Following the PSI as well as the reduction of interest rates in bilateral loans and the deferral of interest payments to the EFSF, Greece is budgeting just over 6 billion euros in interest payments for 2014. That figure in 2011 was 15 billion.

The decision to follow the course chosen in 2010 potentially cost Greece for that year and 2011 close to 15 billion euros in additional interest payments, which were added to the country’s debt pile.

If a different path was chosen, involving a reduction to the principal, favourable coupon payments and maturities being pushed into the future, Greece would have only needed additional funding of significance to support its banking sector following the restructuring. It is worth noting, though, that according to the Bank of Greece the country’s lenders in 2009 had a capital adequacy ratio of 11.7 percent and non performing loans were at just 7.7 percent.

A Greek bailout that had a debt restructuring as a component in 2010 could have amounted to no more than 60 billion euros for primary deficit financing, interest payments, bank support and holdouts. It would have addressed for good the issue of debt that three years on remains the key obstacle for settling the Greek problem. Most crucially, Greece would not have been forced to choke as it did over the last years. The necessary fiscal adjustment would have been smoother and less damaging for so many.

To defend the path that was chosen for Greece - and has left the economy in ruins - on grounds of wider eurozone stability is something that one would potentially be willing to argue. To dismiss outright the obvious solution remains a mystery.

2 Comment(s)

-

Posted by:

"To dismiss outright the obvious solution remains a mystery."

I take it that we are talking about “red herrings” here:

http://www.imf.org/external/np/tr/2010/tr042510.htm

And, why it was that the Greek government in April 2010 “dismiss(ed) outright the obvious solution”, which was placed upon the table – according to the IMF EPE document on the first Greek bailout. Perhaps the resolution of this mystery does not lie in the realm of rational government, but more the domain of irrational political impulses. Could this be the undisclosed true story of the non-recorded despatch of the infamous “Lagarde list”? The French government has never been averse to using underhand methods to pursue its perceived interests. And French interests were indeed at stake at this time with the potential collapse of the French banking sector. Politically compromising information about a negotiating party can be a powerful means of leverage in negotiating a settlement provided you let that party know of the existence of that information. The French authorities had possession of this list from January 2009. -

Posted by:

>"To dismiss outright the obvious solution remains a mystery."

Since many publications have elaborated the most probable reasons, I wonder why the author remains silent about all that. When the financial problems of Greece became obvious there have been the following possibilities:

a) Bankruptcy of the Greek state and some Greek banks

b) A support program including restructuring (with hair cut)

c) A support program without restructuring (no hair cut).

Solutions a & b would have produced heavy losses for major banks in France, Germany and other countries, and it looks most probable that for this reason both government declined that solution.

The well funded critics of plan c which have now been leaked to the public must have been known at that time to the Greek government and I really wonder why they finally did agree?

If the Greek government had refused plan c), bankruptcy would have been a mess, but no real danger to the Eurozone. Since Greece did not implement the required reforms of red tape in bureaucracy and economy, there will be very slow and painful recovery.