-

Is the Greek green transition running out of power?

Is the Greek green transition running out of power?

-

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

-

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

-

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

-

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

-

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

Moments to remember from the euro crisis

Given the concern within the eurozone that the next crisis is just around the corner and that not enough has been done to prevent it, there is a new urgency to learn from our recent past.

The precariousness of the Italian situation, and other threats to the single currency, are the best motivation possible for politicians, public officials, analysts and journalists wanting to assess what went right or wrong in previous years.

The European Central Bank was frequently in the spotlight during the euro crisis and it is now widely acknowledged that its president, Mario Draghi, made the most crucial intervention of any eurozone policy maker during this difficult period, when he delivered his “whatever it takes” speech in London on July 26, 2012.

Draghi’s words, or perhaps more accurately his visible conviction and foresight – as highlighted in a recent Bloomberg feature, which was later backed up by extensive bank liquidity initiatives (OMT, LTRO and TLTRO) that concluded with QE, calmed investors and bought politicians valuable time to tend to the cracks in the single currency.

Like other institutions, though, the ECB’s contribution has also come in for scrutiny. One of the central bank’s most-discussed decisions is the raising of interest rates in 2011, when the crisis was spreading and the euro was teetering. Speaking to a group of journalists at the ECB’s headquarters in Frankfurt last week, the central bank’s former president Jean-Claude Trichet insisted that the decisions to increase the benchmark rate was driven a) by the mandate to maintain price stability (keeping inflation below 2 percent) and b) by the economic data made available to the governing council at the time pointing to this being the right choice. Trichet added that the ECB also launched other “bold measures,” such as the SMP bond-purchasing programme.

Trichet was also questioned about two other controversial decisions he made during his time as head of the ECB, while the crisis was still mushrooming. The first was his apparent resistance to the idea of Greece restructuring its debt after it became the first eurozone country to seek a bailout in May 2010. The other had to do with a controversial letter he sent to the Irish government in November 2010, warning Dublin of the dangers it faced if it did not agree to a bailout.

Greece

On Greece, Trichet argues that under his leadership the ECB played an important role in brokering an agreement in July 2011 that would lead to Athens receiving a second bailout, worth 109 billion euros, which would also include a debt restructuring element.

“It was in July 2011 that the ECB had an overall accord with all governments, including the Greek government, to do what was being done with both the decision to have the debt alleviation for Greece in principle… and at the same time all governments said ‘this is for Greece alone, not for any other country in Europe’,” he said.

The agreement at the July 2011 eurozone summit paved the way for the Private Sector Involvement (PSI) bond swap that was completed in March of the following year. Apart from the fact that the PSI’s effectiveness is still a matter of some debate, whether debt relief earlier (for instance at the start of Greece’s programme in 2010) would have prevented a lot of suffering and economic damage remains a live question.

Trichet was one of the most vocal opponents of debt relief, leading The Economist to label him “intransigent” in May 2011 and accuse him of putting the eurozone’s future at risk. But the Frenchman feared that agreeing restructuring for Greece would make sovereign debt an unsafe asset, which could lead to the collapse of the eurozone’s banking system. The memory of Lehman Brothers’ collapse in the US, and the concomitant problems it caused, was still very fresh in the minds of some eurozone decision makers. As a reminder, German and French banks held close to 100 billion euros of Greek debt at the time Athens signed its first bailout.

Such was the strength of Trichet’s opposition to the idea of a Greek restructuring that he reportedly wrote to the then Greek Prime Minister George Papandreou in April 2011 (as revealed almost three years later by Yannis Palaiologos in Kathimerini) to warn him that if Athens moved forward with its plans to ask for rescheduling of its debt repayments, the country’s position in the euro would be at risk because the ECB might no longer be able to accept Greek bonds as collateral for funding to local banks.

Trichet was questioned last week about whether he regretted writing this letter, especially since debt restructuring took place less than a year later and there continues to be a debate about whether it should have happened much earlier.

“I have no memory of having sent any letter to the Greek government,” responded the former ECB chief.

Ireland

He was also not willing to accept there was anything wrong with the letter he sent to the Irish government several months earlier. In his November 2010 note, Trichet warned Dublin that the ECB would not be able to maintain funding (ELA) for Irish banks at existing levels if the government did not sign up to an EU-IMF bailout. Even more controversially, the letter made broad references to the austerity policies and structural reforms Ireland would have to carry out, as well as cleaning up its banking sector.

When the letter was published in full four years later, The Economist wrote about Trichet’s “poison pen” and argued that the note strengthened the feeling in Ireland, where taxpayers were forced to make bank bondholders whole, that Dublin had been bullied into the programme and the conditions which came with it.

Questioned last week about whether actions such as the letter sent to the Irish government had in their own way contributed to the anti-EU sentiment and populism that has swelled within Europe in recent years, Trichet insisted that he simply conveyed the facts and sought to avert an even worse outcome.

“The ECB in my time helped Ireland more than any other country by far,” he said. “We had at the time liquidity provided representing more than 100 percent of the GDP of Ireland. I conveyed to Ireland the same message as to all other countries in Europe. Doing something that would trigger a new Lehman Brothers was something which was not advisable.”

The Frenchman, who also wrote contentious letters to the Spanish government in 2011 and to then Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi the same year, insists that eurozone policy makers were called on to contain a systemic crisis before it ripped apart the very structure they were tasked with protecting.

“When we intervened to help Greece in May 2010, we intervened simultaneously on Ireland and Portugal to help them because the problems were not only of Greece,” he said. “They were problems of the system.”

Technocracy vs politics

While nobody questions the gravity of the situation that Trichet and other eurozone policy makers faced during the most intense period of the euro crisis, the manner in which they responded cannot be excused from analysis. Firstly, there is a question of policy. For example: Was the ECB right to resist debt relief in Greece’s case? Were the austerity policies or labour market reforms advocated by European institutions the most effective way to deal with the crisis?

These are among the issues that are at the centre of the discussion between eurozone policymakers now, particularly with respect to what role debt restructuring should play and what kind of fiscal capacity there should be to soften the blow of a future crisis, easing the pressure on governments to cut back on public spending or increase taxes.

However, there is also the issue of the process that was followed and whether it was appropriate, safeguarding the integrity of EU institutions, respecting national democracies to the extent possible and strengthening unity between member states.

This is where things get messier because the lines between technocracy and politics become even more blurred. For instance, when Trichet wrote his letter (co-signed by his designated successor and then Bank of Italy governor Draghi) to Berlusconi in August 2011, he used what Reuters called “unusually clear and explicit language” to demand belt-tightening and reforms from Rome before the ECB stepped in to buy Italian bonds.

Austerity and reforms in return for market intervention was a way of binding the Italian government to a certain policy path, assuaging concerns in some European capitals about money being gifted to profligate Mediterranean politicians and shoring up the euro’s weak spots.

The difficulty of striking a working balance was highlighted when Berlusconi soon reneged on the commitments that Trichet and Draghi thought they had secured. This generated a new problem for Draghi once he took over at the ECB as he had to find a way in which the ECB’s market interventions would not ignore the growing concerns about moral hazard in Berlin and some other eurozone capitals. He eventually struck on the compromise of offering OMT only if at least a precautionary European Stability Mechanism programme was in place.

Ultimately, while the details of the policies can be debated endlessly, there can be no doubt the way in which the bailouts were shaped and executed left scars throughout the euro area. In the countries that had to succumb to adjustment programmes, resentment brewed because of the pressure exerted by supposed partners, especially when technocrats appeared to dictate economic and fiscal policy. In the member states that were in better economic shape, moral angst seeped into the political process and made leaders fearful of making bold moves. Both of these developments had a negative impact on the content and manner of the decisions taken. Options were restricted and the atmosphere became combative rather than cooperative.

This chafing exacerbated the crisis and set a negative precedent for dialogue and decision-making within the euro area. Within this context, the role of the ECB and its presidents needs to be scrutinised. The central bank in Frankfurt may have, eventually, played a definitive part in averting a meltdown but there are aspects of its role that leave a bitter taste. One of those is the head of the euro’s lender of last resort writing to elected leaders to insist on certain fiscal policies while delivering an implied threat about future membership of the euro.

If we are to take away something from this experience, let it at least be that this is not a constructive or edifying way of managing our affairs. The economic crisis was confronted, but the way it was done may have sown the seeds for a much more toxic political crisis to come. The signs of such a process are already visible in Italy, where the current government is drawing energy from its supposed resistance to European institutions.

Prevention

For Trichet, the gains of the euro crisis have been that the tools which will, theoretically, make it much more difficult for member states to end up in such a perilous situation again are now being put in place. He suggested that before the crisis, longstanding current account imbalances and cost competitiveness problems were not dealt with.

“This should not be done again,” he stressed, adding that the Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure (MIP), the fiscal compact and the banking union, which is a work in progress, would all help create greater robustness within the eurozone.

“One of the problems is that we concentrate on crisis management, but preventing the crisis was much more important and today what counts is to abide by the rules, to have well-managed governance of the euro area in order not to have these sustained divergences,” he said.

Trichet insists, though, that despite the problems the euro has faced since its launch almost 20 years ago, there are reasons to be content with its course so far and hopeful about its future. The former central banker argues that the euro has managed to become a credible currency in the global economy and showed its resilience during the crisis, noting that the euro area had 15 countries when Lehman Brothers collapsed but has added another four member states since then.

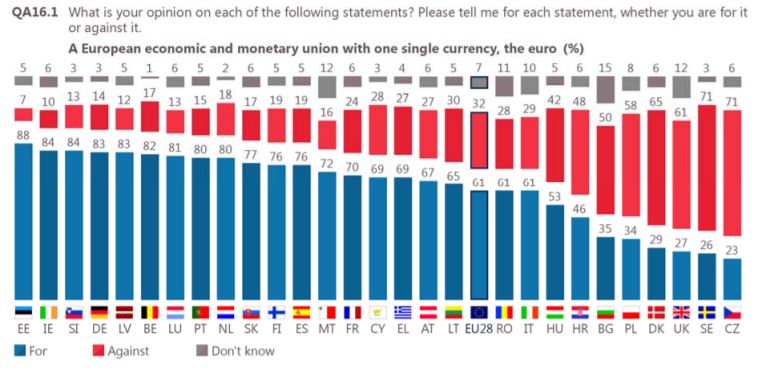

Also, the ex-ECB president points to support for the euro remaining strong (according to the latest Eurobarometer survey) despite the tribulations of the last decade.

Finally, he underlines that in terms of growth per capita, the euro area has been on a par with the US over the last 20 years despite commentators often arguing that the Americans dealt with their financial crisis more convincingly than the Europeans.

Nevertheless, with political and economic factors pushing Italy towards the precipice, there can be no complacency within the single currency area. Greece, still the euro’s weakest link, has seen its bond yields rise to unsustainable levels despite exiting its third programme in the summer. Concerns also abound regarding Italy’s debt pile and what financial contagion it could release, while the potential political impact of the stand-off between Rome and Brussels, especially in view of next year’s European Parliament elections, is also a cause for concern. Meanwhile, the eurozone’s banking system, where many lenders are saddled high non-performing loans and low profitability, continues to be a source of worry for analysts.

“We should be fully conscious of the fact that a single currency of that dimension, with 19 countries, has to be governed,” Trichet emphasised last week.

There are evident complexities involved in bringing together so many countries that have significant historic, societal, economic and political differences and getting them to share a currency, one which remains a work in progress 20 years after it was launched. Even after a decade that proved devastating for so many economies in the eurozone, it is still difficult to get the representatives of the member states to agree on the exact form that banking union will take, how to reform the stability and growth pact or what kind of stabilisation budget the single currency area needs.

If decision makers do not move quickly and decisively, we risk ending up in a position where last-ditch threats will again become a key policy tool. Recent history suggests, though, that even if this is effective in the short-term, it will leave longer-term problems. This makes it imperative that we evaluate openly and honestly the errors of the euro crisis, whether they are fresh in our memories or not.

*You can follow Nick on Twitter: @NickMalkoutzis