-

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

-

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

-

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

-

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

-

15% Uncertainty: Greece, Europe and the tariff shockwave

15% Uncertainty: Greece, Europe and the tariff shockwave

-

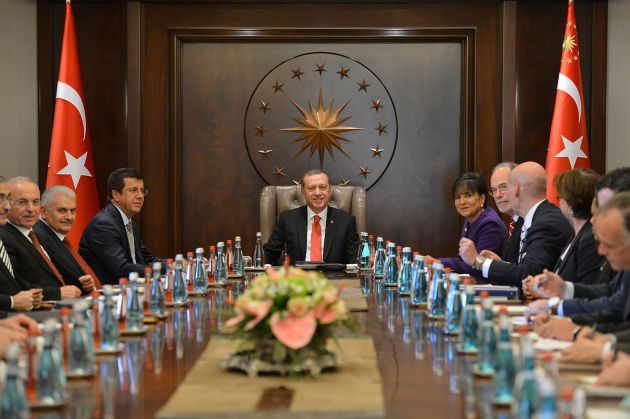

Summit of transactions – Erdogan and Trump

Summit of transactions – Erdogan and Trump

What's behind Erdogan's decision to wave migrants through to Greece?

The decision taken by Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan earlier this month to allow asylum seekers and migrants to travel to Greece took some people by surprise but it was a move that had been in the making for some time.

Under pressure at home and facing difficulty with his military operations in Syria, Erdogan felt it was time to put European leaders on the spot and seek more assistance from the EU.

In Greece, the tension generated on the Evros border and in the Aegean has been viewed mostly through the prism of fraught Greek-Turkish relations. But this has obscured the bigger picture and a broader understanding of what is at play.

MacroPolis spoke to Wolfango Piccoli, co-president and director of research at Teneo, about what lies behind Erdogan’s diplomatic moves, why Greeks may be misreading the situation and how the situation could develop in the coming weeks.

What triggered Erdogan’s decision to give free passage to refugees and migrants? Was it events in Idlib province or are there other factors that brought this about?

We need to take a step back here. Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) experienced a historic loss in local elections in 2019. It lost most major cities to the opposition, including Istanbul, Ankara, Antalya, Mersin, and Adana. One of the primary reasons for these losses was the widespread discomfort felt due to the Syrian refugees in Turkey’s urban centres. Recent public opinion polls confirm that Turks see the refugee issue as one of the most important problems facing the country. After the poor performance in the local elections and in an urge to demonstrate that the government is in control of the situation, Ankara’s attitude to Syrian refugees changed last summer. Security forces started to round up Syrian refugees, send them back to the Turkish provinces where they were registered, deport some, and encourage others to move to areas controlled by Turkey in northern Syria.

This is also when Turkish President started to publicly criticize the 2016 deal with the EU, saying that the EU member states failed to meet their commitments and that Turkey was only getting “peanuts” for all the assistance provided to the refugees. Erdogan indicated the overall cost for Turkey at around Eur 40bn.

It is against this context that the recent events in Idlib need to be considered. The advance of the regime forces in Idlib created a humanitarian disaster that western countries have largely ignored. There are around 1 million civilians, many of whom have already been displaced several times from elsewhere in Syria, who are now displaced next to the Turkish border.

Facing western indifference toward Idlib and irked by the high casualties suffered in the north-western Syrian province, Erdogan took the cynical decision to use the refugees to seek leverage over the EU.

How much political pressure is Erdogan under in Turkey to address his own refugee challenge, given that there are more than 3.5 mln registered Syrians in the country and reports of around 1 mln more on the other side of the border?

The refugee issue is politically toxic in Turkey. The challenges faced by the economy and the concomitant higher unemployment have created additional pressure on Erdogan to act. Turkey hosts nearly 4 million refugees, mainly from Syria, and now it fears another large-scale refugee influx from Idlib.

Refugees from Syria’s war were greeted with open arms when they began arriving in Turkey nine years ago. No longer. Polls show that over 80 pct of Turks want the refugees their country hosts to go home. Only 2.4 percent of Syrians are in camps, with the remainder mostly in Turkey’s cities. Syrian refugees have access to free healthcare and education but poverty and the need to work coupled with language difficulties means that around 40 pct remain out of schools.

It is in this context that the current push for a safe zone must be seen. This is not a new idea. Turkey has floated it numerous times and has operationalised it in military operations in northern Syria. Recall that Turkey carried out its first military offensive in Syria in 2016 to target ISIS.

The reports of migrants being bussed to the border, or dinghies being escorted by the Turkish coast guard, have fuelled the use of the term “hybrid war” in Greece and have created the impression that Erdogan is trying to destabilise the country. Is this a fair assessment or a misreading of what’s going on?

To put it bluntly, Erdogan does not care about Greece. Erdogan’s playing the refugee card is certainly despicable, but it is not part of a sinister plot to destabilise Greece. Under pressure at home and facing a possible debacle in Idlib, Erdogan weaponized the refugee issue to secure more help from its European partners. And unlike 2016 is not just about money.

Domestic considerations are also a factor in his decision to push migrants towards the border with Greece. With news of Turkish casualties from the Idlib front and the government’s Syria policy under growing public scrutiny, Erdogan must also hope that polemic on migration will shift the domestic debate away from Syria and towards some crowd-pleasing bashing of Europe. This is also why the government is enthusiastically exaggerating the number of refugees who have left the country. The figure used by the Turkish media is around 130 to 140 thousand.

Another theory being put forward is that the ushering of migrants to the border is part of an effort by Erdogan to put pressure on EU leaders so they can in turn urge Vladimir Putin to allow the creation of a safe zone in northern Syria. Is this plausible? Can the EU, or specific member states such as Germany and France, wield any influence with regard to Syria? What can we take away from Erdogan’s recent meeting with Putin?

Erdogan is asking the EU, and especially Germany and France, to put pressure on Russia to not to intervene in the military campaign Turkey is conducting in the north of Syria against the Syrian army, and for it to help in establishing a security zone in the Idlib province where he wants to settle the refugees.

In addition, there is a desire to revisit the 2016 deal with the EU to secure a new tranche of financial aid that should come with less conditionalities. The existing deal only allows for payments to specific institutions and projects (as opposed to a direct payment to the Turkish government) – this has long frustrated Ankara.

While these goals may never be achieved, Erdogan has already managed to attract plenty of attention to the plight of the civilians stranded between Idlib and the Turkish border. The President of the European Council Charles Michel was in Ankara last week and Erdogan met the EU and NATO top brass in Brussels on 9 Match. Erdogan is now pushing for a summit with German Chancellor Angela Merkel and France President Emmanuel Macron.

Meanwhile, the March 5 meeting between Erdogan and his Russian counterpart, Vladimir Putin, has brought the issue of Idlib to an uneasy standby. The deal is a temporary measure that falls well short from providing a lasting solution to the Idlib question. But it offers Russia and Turkey the chance to reduce tensions in their bilateral relationship and shows that both sides are keen to avoid an open confrontation.

It is only a matter of time before Damascus starts pushing for Idlib again and a new crisis emerges. And just like over the past week, Ankara will have no good options available.

What was Erdogan’s main goal when he visited Brussels on Monday? Is he aiming for the 2016 EU-Turkey agreement to be redrafted, perhaps with more European funds for Ankara, maybe even for reconstruction in northern Syria, or a fresh look at the Customs Union and visa requirements? What did he come away with from Brussels?

The talks in Brussels were inconclusive. This is hardly surprising given the existing tense atmosphere between Turkey and the EU and the need for both sides to save face. For Erdogan, it was mainly an opportunity to bring back to the table a long list of grievances and reiterating that the EU is not keeping its side of the bargain.

Despite the lack of any agreement, the two sides will continue working together to clarify the implementation of the 2016 deal. Plus, the EU has not ruled out providing Turkey with additional financial assistance.

The bottom line is that from Erdogan’s perspective the only meaningful interlocutors are Merkel and Macron. And in the bargaining with them, Erdogan will ask for the maximum – including visa liberalisation for Turkish citizens and an updated customs union – to secure what is more realistic.

How do you see things playing out in the coming weeks? How can the current situation on the Greek-Turkish border and in the Aegean de-escalate?

Looking ahead, the next signpost is whether the “Syria summit” with Merkel and Macron will happen or not. Erdogan indicated it may take place on March 17, but neither Paris nor Berlin have officially confirmed.

The situation at the Turkish-Greece border is likely to remain unsettled and prone to renewed bouts of tensions. It is too early for Erdogan to de-escalate the situation. In his view, the ball is now in the EU’s court.