-

Is the Greek green transition running out of power?

Is the Greek green transition running out of power?

-

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

-

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

-

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

-

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

-

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

Greece takes first round against Covid-19 but fight continues

In the wake of the devastating impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on Europe, Greece has emerged as an unlikely role model, with international media referring to the “Greek model” of crisis management, and praising the country’s seeming transformation from the black sheep of the European family to a champion of rational policy-making and a beacon of good behaviour.

As of April 20, Greece has recorded only 2,245 confirmed cases and 116 deaths from COVID-19 since the first case was announced on February 26. Hospitalisations in ICU units peaked at 93 patients on April 5 and all indicators of the spread of the disease have been declining since.

In news outlets as diverse as Bloomberg, Al Jazeera and The Guardian, the Greek government is given credit for acting swiftly on scientific advice despite having only recently emerged from a decade-long financial crisis. A number of commentators credit the country’s surprise success in tackling the pandemic more or less directly to having recently elected a moderate conservative government, blaming populist politicians in Italy and Spain for their respective failure to manage the crisis.

Greece has shown surprising resilience in limiting the spread of the virus and minimising its impact on the national health system. However, the reasons behind this initial success are probably more complex than these narratives imply and will only be understood in time. Greece still faces real constraints upon its healthcare capacity, which has not been seriously tested to date, while the political context is not as benign as some interpretations suggest.

We start by considering the capacity of the Greek health service, before looking at the political context for the country’s COVID-19 response and its possible implications for the future.

Healthcare capacity

Like most European countries, Greece has a public health system, which is funded partly through taxes and partly through compulsory social contributions, complemented by private healthcare providers. The healthcare system has been hit by severe funding cuts in recent years, but also suffers from structural weaknesses and imbalances, which could make it vulnerable to a crisis.

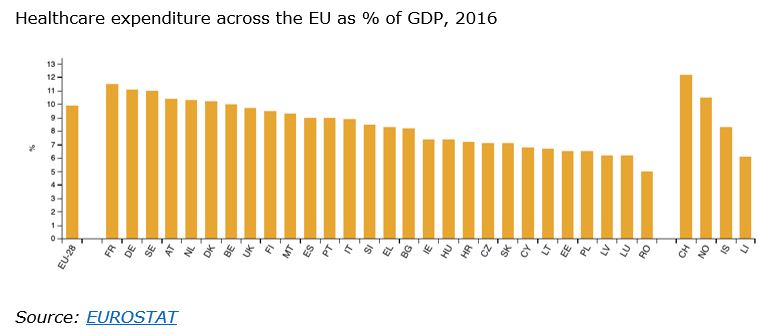

In 2017, Greece spent 8 percent of its GDP on healthcare, substantially below the EU average.

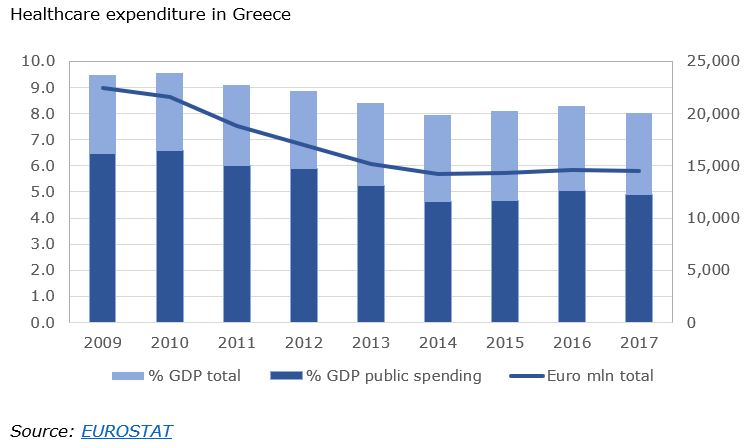

Healthcare expenditure has been slashed from its high point of 9.5 percent of GDP in 2009 as part of the country’s economic adjustment programme mandated by the terms of successive lending agreements. In cash terms, Greece spends a third less on healthcare than it did prior to the financial crisis.

Public spending on healthcare was capped at 6 percent of GDP by the adjustment programme and currently stands at just below 5 percent GDP, with the remainder topped up by private spending by individuals.

Spending cuts have affected most aspects of public healthcare.

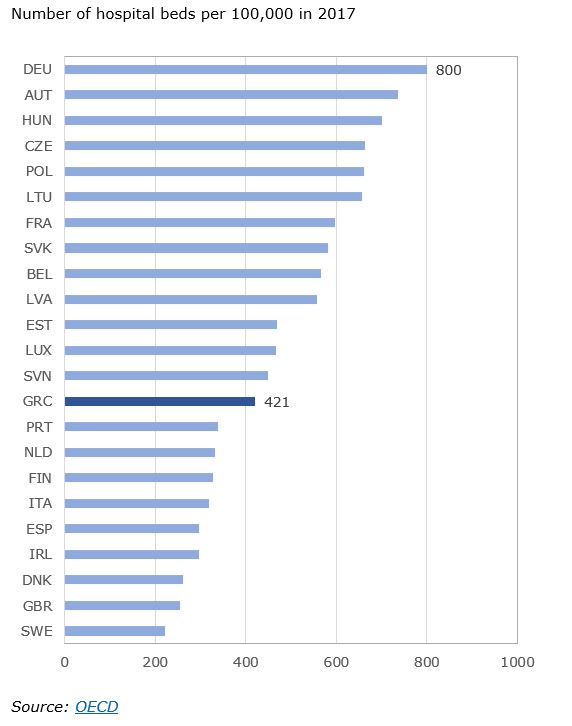

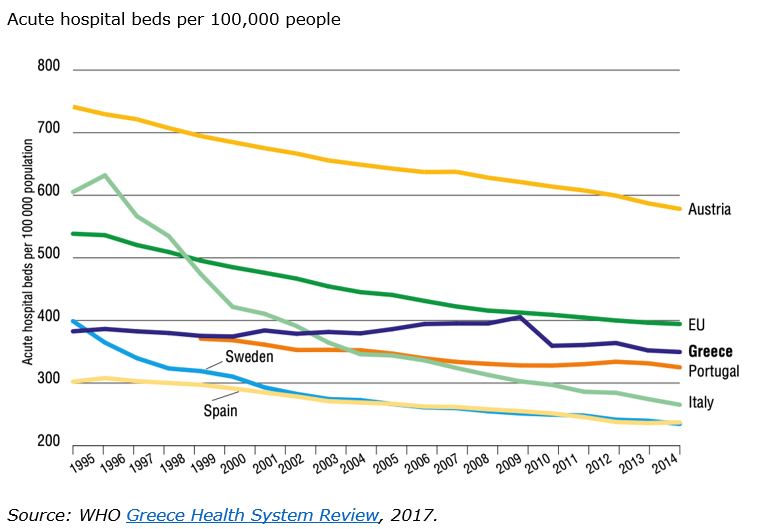

Greece fares below the European average in terms of numbers of hospital beds, with 421 beds per 100,000 people, compared to 800 in Germany, the top-ranking country. In terms of overall bed capacity, it is ahead of many more prosperous EU countries, including the Sweden, the UK, Denmark and Italy.

Roughly two thirds of all hospital beds are in the National Health System, and one third in the private health sector.

The number of hospital beds has been reduced as a result of spending cuts - although the reduction was perhaps not as drastic as those taking place across most of the EU over the last two decades.

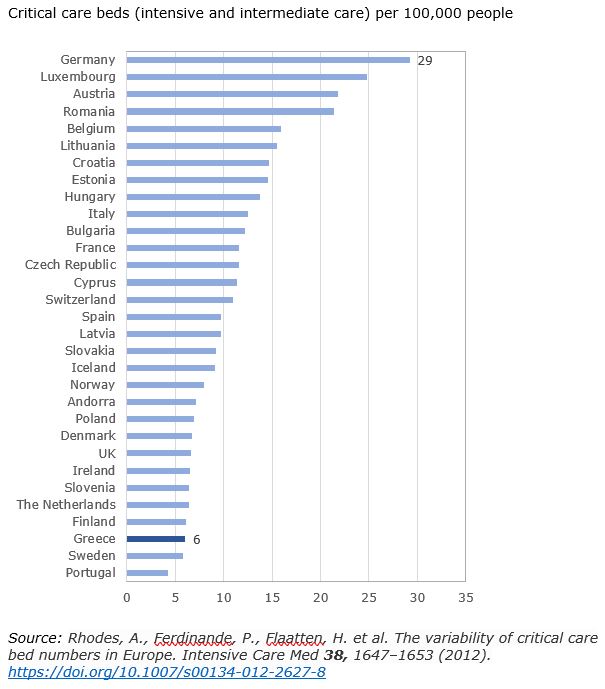

Nevertheless, intensive care capacity, which is proving crucial for dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic, is in short supply. A 2012 study ranked Greece among the least well-provided countries for critical care beds in Europe, with 6 beds per 100,000 people in stark contrast to Germany’s 29, and just over half the European average of 11.5.

Workforce

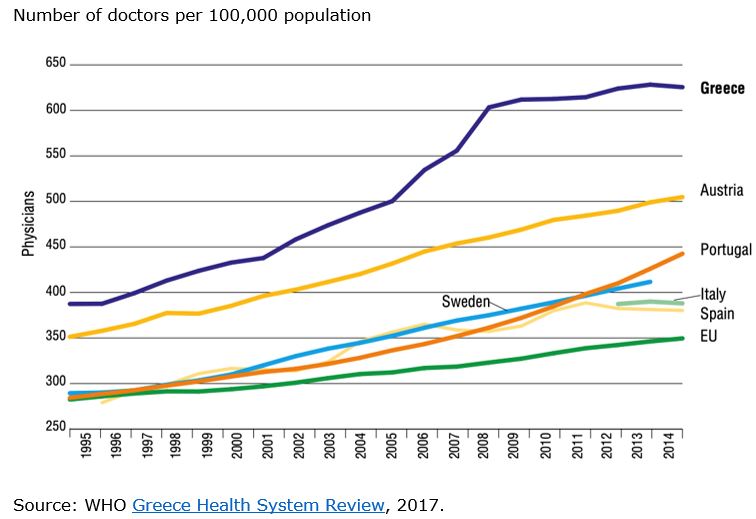

Despite the well-documented flight of highly skilled medical personnel in recent years, Greece still has the largest number of doctors relative to its population in Europe, with over 600 doctors for each 100,000 people - almost twice the European average of 350. This headline figure perhaps overstates the true availability of physicians, as it includes non-practicing doctors. In addition, only about a third of registered doctors work in the National Health Service (24,636 in the latest count), while a large portion of them are specialists.

There are only 39 general practitioners for each 100,000 people in Greece compared to the EU average of 80.

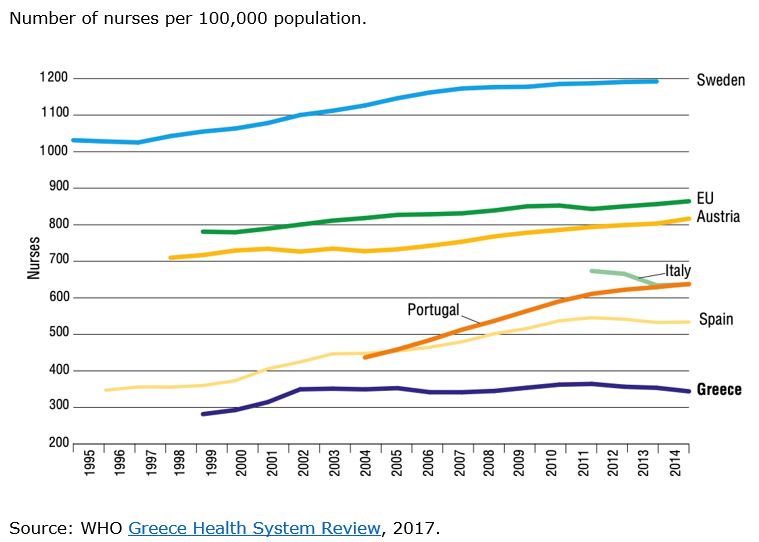

Greece also has the lowest number of nursing staff relative to population in the EU, with 344 per 100,000 people, less than half the EU average of 864.

Added to resource shortages, Greece has been juggling several separate healthcare reforms in recent years as part of the economic adjustment programme, most of which are still in progress.

Typical of the state of flux in the healthcare system, for a period between 2009 and 2016 around 2.5 million unemployed and underinsured were left without comprehensive health coverage. While universal access is now ensured by law, in practice access to healthcare remains unequally distributed across the regions, while primary care has historically been a weak point.

A reform programme started in 2004 included devolving responsibility for regional healthcare from the Ministry of Health to regional health authorities, however that process remains incomplete, and planning, organisation and provision remain highly centralised. Despite a reform of primary care announced in 2017, the system remains a patchwork of public and private providers, at best challenging for patients to navigate, and with problems in coordination between different stages of care and different specialties.

Unsurprisingly, investment in the public health system has been a politically controversial issue, which has come to the fore with a vengeance thanks to the pandemic. However, the vociferous rhetoric exchanged between parties belies the fundamental fact that successive MoU-era governments had little freedom of movement, while their approach to healthcare in the months since the end of the programme has not differed much in practice.

Hiring across the public sector was effectively frozen under the terms of the economic adjustment programme, and this included the healthcare sector. The census of government employees shows the permanent headcount for the Ministry of Health, to which most National Health System employees belong, remained stable over the period 2015-2019 (79,533 were counted in December 2014 compared to 79,112 in July 2019).

Nevertheless, the previous government was able to claim to have made 19,500 new appointments in healthcare over that period. Roughly 8,500 of the appointments were permanent, and included medical and nursing staff as well as administrators and other support functions. Permanent appointments, however, barely made up for departures from the health service, primarily through retirement – in total 10,862 staff left the Health Ministry during the period, while 8,232 joined. The remaining hires were made under a variety of fixed-term contracts through special budgets, for example for migration-related programmes or paid work experience for unemployed graduates.

In the last months of its term in 2019, following the exit from the MoU and the relaxation of hiring restrictions, the SYRIZA government announced a programme of 10,000 appointments in the health system over a four-year period, of which 2,500 were slated to take place before year-end. The appointments were to abide by a 1:1 replacement rule (one hire for each departure) and would therefore amount to a replenishment rather than an increase in staffing levels.

Despite advertising a radical overhaul of the healthcare system with greater private sector involvement, hospital mergers and efficiency measures, the New Democracy government which came to power in July 2019 pledged to respect the 1:1 ratio for the health service, and to continue the hiring programme put in motion by their predecessors. A statement made in January 2020 referred to 700-800 appointments in the health sector delayed from the previous year and scheduled to be completed in May, in addition to 2,450 posts advertised, which were effectively a continuation of the SYRIZA programme.

Covid-19 response

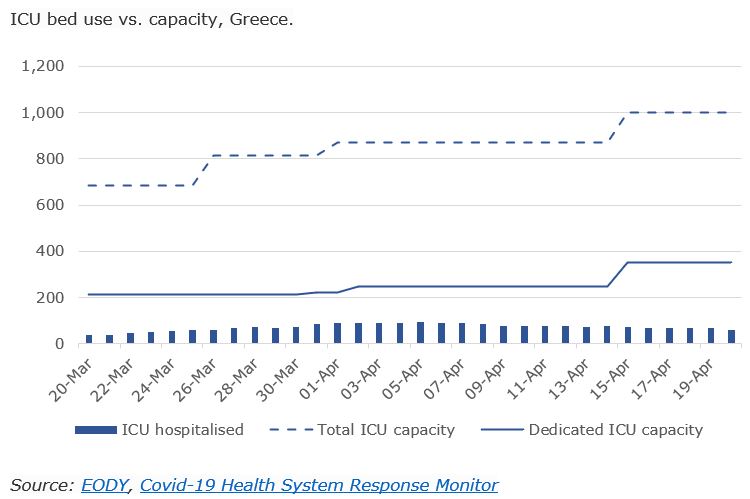

According the Ministry of Health, going into the pandemic the National Health System had at its disposal just 565 ICU beds. The government response has been to increase ICU capacity to 1,000 beds through a combination of upgrading and repurposing wards in public hospitals, making use of military hospitals, and leasing capacity from the private sector. At the time of writing, 350 ICU beds were set aside for COVID-19 patients, and over 3,672 hospital beds in total were assigned to the treatment of coronavirus patients.

The ministry’s planning foresees increasing COVID-19 ICU capacity to 400 beds by the end of April and 1,000 beds by the end of May by erecting temporary wards.

In response to the pandemic, the health ministry launched fast-track procedures to fill 4,200 temporary posts, 654 for doctors and the remainder for nurses, administrators and paramedics. According to official figures, over 2,300 of the posts were filled by early April 2020.

In the event, only about a third of the dedicated ICU beds have been used on any given day since the outbreak of the pandemic, as numbers of serious cases have remained at relatively low levels.

Much of the strain was felt in some of the smaller regional hospitals and health centres on the frontline of localised outbreaks. A number of local health centres were forced to close temporarily after members of staff became exposed to coronavirus.

The recognition that the country’s health system could not sustain a large-scale surge in hospital admissions undoubtedly played a major role the Greek government’s decision to act to contain the spread of the virus. According to reports, monitoring and planning for the pandemic was initiated as early as January.

By the time the virus made its first documented appearance in Greece on February 26, Italy was already counting 322 confirmed cases and 11 deaths, while several of its northern provinces were being put under lockdown. In the ensuing couple of weeks hospitals in Lombardy – a far better-resourced system - were starting to buckle under the strain of a major outbreak. Italy offered a cautionary tale very close to home of how badly things could go wrong in the absence of a strong response.

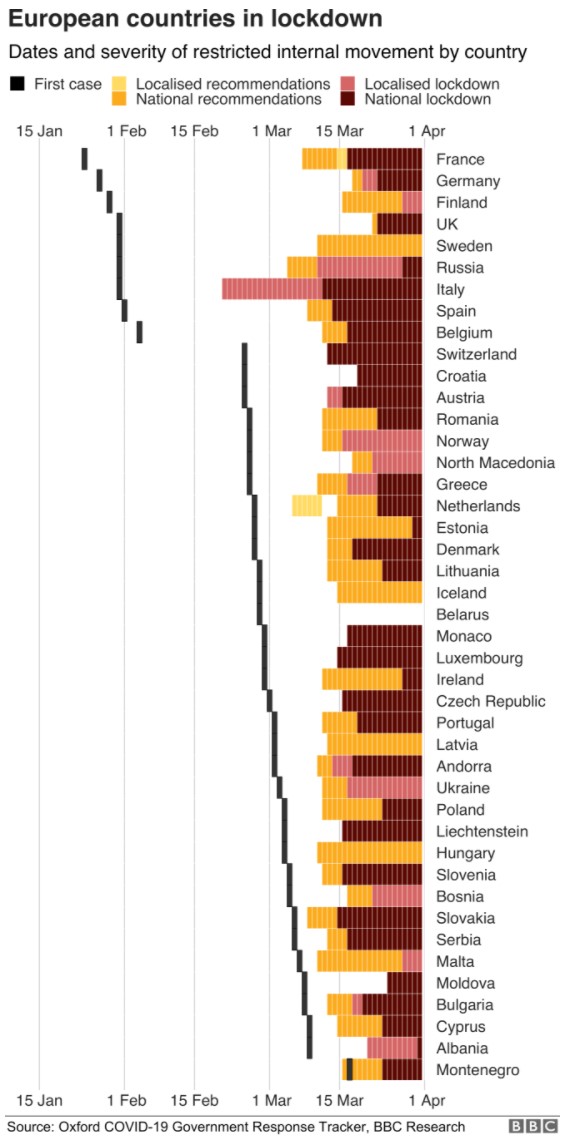

Greece’s lockdown was put in place gradually between March 9 (two days prior to the first recorded death from Covid-19 in the country and three days before the WHO declared the outbreak a pandemic) and March 22. The measures started with bans on large public events including national league football matches and school closures, and culminated in the shuttering of non-essential businesses and restriction on movement. The response followed a template which was established through rapid (and in many respects costly) trial-and-error across Europe.

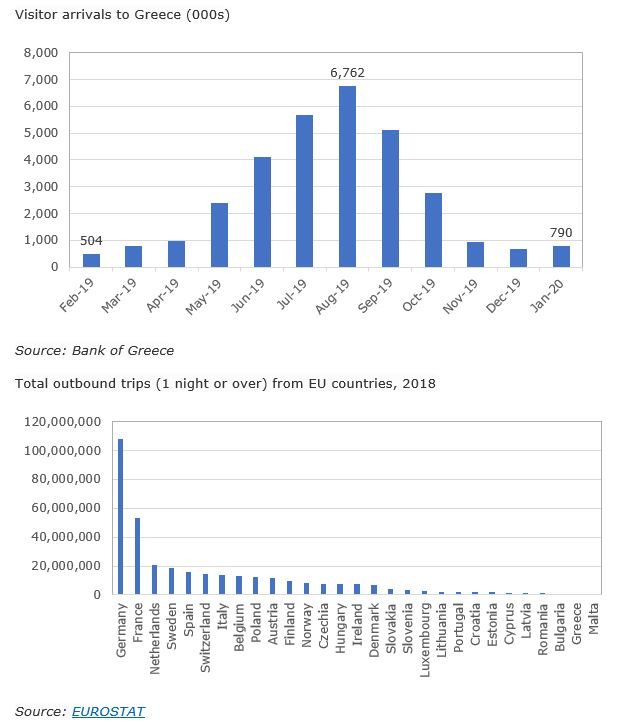

Certain circumstantial factors gave Greece an advantage in responding to the pandemic. The most crucial one was timing. Greece, along with its southeast European neighbours, recorded its first case of COVID-19 three or four weeks later than much of western Europe, and was therefore well behind on the epidemiological curve. Contacts patterns probably played some part in this – for example, the fact that winter is low tourist season meant less international traffic in and out of the country, limiting the opportunities for exposure to the pandemic, while Greeks undertake very little international travel compared to European peers.

A timely policy response, recognising the impending threat and acknowledging the country’s limited capacity to cope, gave the health system breathing time to prepare for a surge in demand to the extent possible. However, there remain real limitations to what Greece can achieve with its strategy and resources, and some of the weaknesses in the system could come to the fore as the pandemic moves to its next stages and policymakers start to consider easing the lockdown.

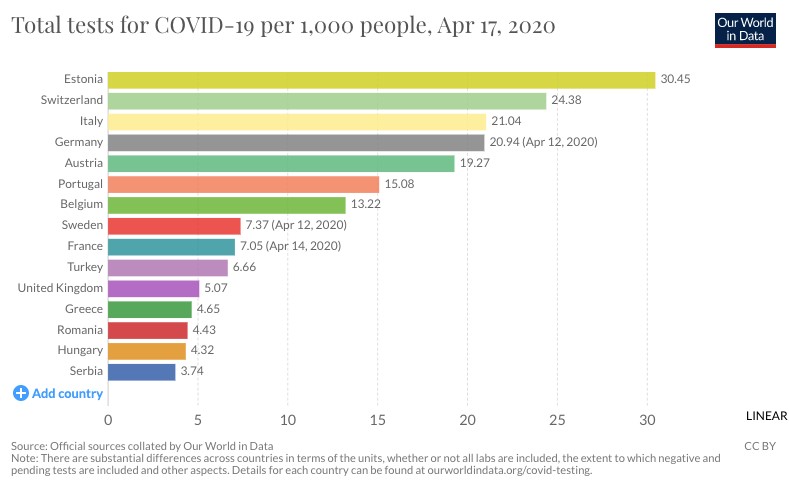

Testing is one potential bottleneck. So far Greece has demonstrated success in containing the disease in the absence of large-scale testing capacity. At 4.65 tests per 1,000 people, Greece still has one of the lowest COVID-19 testing rates in Europe, a fact which has caused some public anxiety and attracted political criticism. The testing strategy, focussing tightly on high-risk groups and symptomatic patients, was almost certainly circumscribed in the early days by lack of resources. Mass testing on the scale of countries like Germany is still not planned for the immediate future, but diagnostic capacity is being expanded with mobile testing units, and antibody testing is also being planned for a later stage. Ensuring adequate testing capacity at the right time will be one of the main challenges in the next stage.

The supply chain for critical equipment and hospital supplies has been another potential weak point in the health system. When Greece entered the market for protective equipment and ventilators, global competition was already driving prices up and constraining availability. As a result, most of the shipments obtained in recent weeks have been in the form of donations by other governments (including China and the UAE), charitable foundations tied to Greek shipping interests, or corporations.

Much of the information pertaining to the availability of equipment, supplies and testing capacity is not publicly available, making it hard to assess the true state of the country’s readiness for a resurgence of the virus.

Since the outbreak of the pandemic, PM Kyriakos Mitsotakis has pledged to bring national ICU capacity closer to the European average by adding “hundreds” of beds. Mitsotakis has also hinted that he wants an upgraded health system to be part of his government’s legacy.

While the opposition has bristled at his extravagant claim to have “accomplished in five weeks what hadn’t been done for decades”, there is little substantive disagreement with the plan, and criticism has been limited to the speed of implementation, the reliance on fixed-term contracts, and the cost of leasing private beds.

A report by the Parliamentary Budget Office has called for more public investment in the health system as part of a post-coronavirus economic stimulus package. The report argues for healthcare spending to be tipped in favour of staff and equipment and away from pharmaceuticals, which currently absorb a disproportionate part of the budget (1.2 percent of GDP, second only to Germany’s 1.3 percent GDP).

Political context

Journalistic assessments of the Greek response to the pandemic tend to place great emphasis on the role of the country’s political leadership while underplaying other factors such as timing and geography which undoubtedly helped to minimise the threat.

Political leadership is important, and we can now point to several counterexamples of poor or questionable political judgements made in the face of the pandemic. At the time that Greece was introducing restrictions, alternative policy responses were still being debated elsewhere. Wealthier countries such as the United Kingdom and the United States delayed their response for fear of the economic costs of a lockdown, while others, like Sweden and the Netherlands took a softer approach citing consensual social norms. Some of these choices are already taking a heavy toll; others may or may not prove sustainable.

The decision to put Greece in lockdown was a starkly pragmatic choice in light of the country’s known capacity limitations. The decision was timely, rather than precarious or cutting-edge, and it was dictated by necessity rather than inspired by a particular political philosophy or style of government. It is to the credit of the decision-makers involved that they recognised their predicament and saw that there was no margin for denial or experimentation.

However, the limitations remain, and many of them are directly linked to the political context.

At present there is a broad-based consensus behind the pandemic response measures, in spite of economic shock they are expected to trigger. More than 80 percent of the public agree with the measures, including a majority of SYRIZA voters, while one in ten are in favour of even stricter rules. New Democracy is enjoying a 23-point lead in polls over SYRIZA and Kyriakos Mitsotakis’s performance as PM has the approval of almost two thirds of the public. International plaudits for the country’s success against the virus so far, reported regularly in the domestic media, have helped to boost morale and promote a sense of pride and national purpose.

The national consensus, however, is likely to be fragile, as it is not a consensus built on dialogue. When the pandemic made its first appearance in Greece, the country was already on a “war footing”, and the government was enjoying unprecedented approval ratings as the result of a border dispute with Turkey. When Mitsotakis took a hardline stance on migrants trying to cross into Greece, it earned him the support of 90 percent of the public. The government was cheered on by the overwhelming majority of the country’s media. The opposition was blindsided and trailing in the polls, and the government’s critics, including journalists and human rights advocates, were painted as purveyors of “fake news”. The border crisis served as a distraction from the first signs of fatigue for the government, as it began to confront politically unpopular tasks, facing public unrest in response to its migrant resettlement programme and preparing to enforce home foreclosures.

In the event, it was able to transition directly from confronting the “asymmetric threat” of migrants at its borders to “fighting the invisible enemy” of the pandemic without pausing for debate. The sense of a rolling national emergency undoubtedly helped secure the public’s compliance with lockdown measures.

Unlike other parts of the world, there have not been voices in the media clamouring for the government to lift restrictions and restart the economy. The only organised resistance to the lockdown came from the Greek Orthodox church, which was initially reluctant to stop offering religious services and close churches to the public, while elements in the government continued to give mixed signals to worshippers up until just before Easter. Compliance levels with movement restrictions and business closures have been high (the total of 46,141 fines for unjustified movements since the start of the lockdown equate to just 0.4 percent of the population), and sporadic anarchist graffiti linking lockdown measures to state repression has been the only other visible hint of dissent.

However, hard times lie ahead.

The lockdown will cost the Greek economy more than most, thanks to its heavy reliance on tourism, shipping and the SME sector. Most forecasts of the pandemic’s impact agree that the economic shock will be considerable and could set the country back several years on the path to recovery.

A stronger health system will undoubtedly put Greece in a better position to manage a second wave of the pandemic, however as the roadmap for the next few months begins to take shape it is becoming clear we should anticipate a series of rolling lockdowns that national governments will have to manage according to their own healthcare capacity. Less capacity could translate into longer, or stricter, and by extension more costly lockdowns. The calculus of economic versus human cost is one that will continue to evolve. It is likely to become harder for governments to gain public trust and compliance as the economy worsens, especially if the negative effects are unevenly distributed as studies in other countries lead us to expect.

Even by the yardstick of the recent past, the economic consequences of the present measures will be hard to manage, and the “rally behind the flag” effect will soon evaporate. Lifting and then potentially re-imposing lockdown measures may well prove politically contentious, with some sectors of the economy or some social groups suffering more than others, while key prerequisites for re-starting the economy, such as the return of foreign visitors, depend on global developments outside the national government’s control. By autumn, when experts predict a second wave of the pandemic, public sentiment could be very different and the challenge of containment much more daunting.

*You can follow Georgia on Twitter: @georgia_nakou_

2 Comment(s)

-

Posted by:

I really enjoyed reading your well-balanced analysis. Your attempt to give more than one side to the story was both informative and refreshing. many thanks Anna Ritsatakis

-

Posted by:

Thanks for this excellent, balanced, thorough analysis. It has been hard to get behind the media swooning to the realities of luck, timing, and appropriate actions by the government. The rickety state of the national health care system is clearly exposed in this analysis and the chart showing the dates of government response belies the fawning press coverage of Mitsotakis. Next time, Greece may not be so lucky