-

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

-

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

-

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

-

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

-

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

-

15% Uncertainty: Greece, Europe and the tariff shockwave

15% Uncertainty: Greece, Europe and the tariff shockwave

Greece's post-lockdown hubris

Hailed as one of the heroes of the first phase of the Covid-19 pandemic, Greece seems to have sacrificed its early advantage to political mishandling.

It is common to point the finger at the decision to reopen the country to tourism soon after bringing infections under control, however the evidence suggests that a tragic failure of public engagement in the period after the lockdown was lifted in Greece is at least as much to blame for an upsurge in infections.

This increase threatens the country with a second, and more ferocious, wave well before the autumn.

After lockdown

Greece managed to flatten the infection curve with minimal casualties and limited impact on its already overstretched healthcare system thanks to a two-month strict lockdown, which authorities began to lift in early May.

As early as June 13, Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis declared the tourist season open against the picture-postcard backdrop of the Santorini sunset as borders reopened to visitors from most neighbouring countries and international flights recommenced from a number of European destinations.

At the end of July, the country’s infection record still looked relatively good. Greece had registered below 4,500 confirmed infections from the start of the pandemic, and just 206 deaths in a population of around 10.5 million. The number of patients intubated in ICUs had receded to single digits, having barely exceeded a third of available capacity at the height of infections in early April.

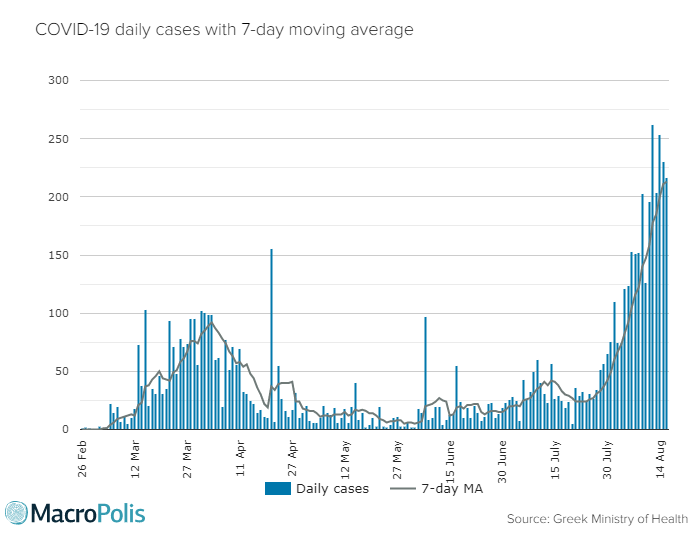

But things were already starting to take a worrying turn, with the number of new cases gradually edging up. On August 1, the 7-day average of new daily cases exceeded 50 for the first time since the height of the first phase in early April. By August 15, the number had exceeded 200.

For many Greeks and outside observers, the developments confirm the underlying fear that opening the borders to welcome tourists would undo the sacrifices made during the lockdown. The decision to start the tourism season was always going to be a calculated risk, and caused a degree of anxiety in the public, with opinion polls showing a sharp increase in the number of people concerned about the virus with the opening of borders at the start of July.

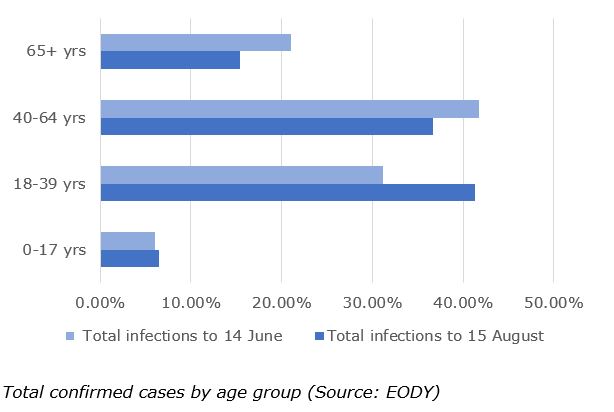

However, as the situation evolves it is becoming increasingly clear that tourism was only one contributing factor in the resurgence of the virus. Over the period between June 14 and August 15, imported cases accounted for 26 percent of new recorded infections, while traced contacts made up 41 percent and untraced infections in the community account for just under 34 percent. More cases have been detected in younger people, many of whom are asymptomatic, partly as a result of more widespread testing.

Meanwhile, several well-publicised “superspreader” events centred around wedding parties and other social events in local communities have highlighted how tenuously the general public has embraced the scientific guidance in the post-lockdown environment.

What went wrong?

Signs that something was amiss appeared early, even before the lockdown began to be eased. Although opinion polls showed a consistently high approval rating – hovering around the 90 percent mark - for the government’s handling of the crisis and the measures imposed, pockets of resistance were not hard to spot.

Among the warning signs were the government’s persistent reluctance to include church activities in its general measures for indoor spaces, gatherings, and more recently mask-wearing, and the clergy’s refusal to comply with a voluntary guidance to protect their – mostly elderly – flock. It is fortunate that the anti-lockdown or anti-mask message has not been consciously adopted as a political stance by any mainstream party or media outlet in Greece, however social media provided another forum for sceptics and conspiracy theorists of all stripes, whose stock-in-trade has become fairly prevalent among the public at large: More than half of respondents to a survey conducted in mid-June said that they believed Covid-19 to be a human creation, while one in three believe that it is being used to push for compulsory vaccination.

In the physical world, informal parties in squares began to crop up in the days before bars were allowed to open, largely attended by young people keen to let off steam after several weeks “in quarantine”.

Variations on these phenomena have been spotted around the world at about the same time, as countries started to ease their lockdowns. Greece additionally had to contend with the prevention paradox: having escaped the first wave lightly, with only a small minority of people having experienced the disease in their immediate circle, the risk has become to be perceived as remote.

As a result, observance of prevention measures post-lockdown – for example the correct wearing of masks – has pushed the boundaries of conformity. One survey conducted in mid-July confirmed what was evident from casual observation: one in two respondents had relaxed or abandoned hygiene measures since the lifting of lockdown, while almost two in three said they would not react to any breaches.

The political debate has largely skirted around these issues by creating a false dichotomy. Throughout its response, the government has placed a strong emphasis on “personal responsibility” and more recently appealed to the mythical Greek virtue of “philotimo” (sense of pride/honour) as the main weapon in the fight against the virus. The opposition has accused the government of shifting the responsibility (and blame) for the pandemic entirely onto citizens while evading the state’s responsibility to protect and care for the vulnerable, calling for more widespread diagnostic testing and more investment in the healthcare system.

The truth, as usual, lies somewhere in between. Preventing the spread of a highly contagious disease was bound to require a massive collective effort by individuals, but harnessing individual behaviour to a collective cause in the context of a democratic society is a task of persuasion. In this respect, the government appears to have dropped the ball early on, and the reasons behind this failing are political.

Missed opportunities and wrong signals

The government’s attempt at a public information campaign got them into hot water a few news cycles ago, for seeming to award advertising funds preferentially to friendly media outlets. A total of 20 million euros was spent on Covid-19 awareness campaigns to promote the “stay at home” message during lockdown, and its successor the “stay safe” campaign for the easing period. The criteria for distributing the funds were never published despite repeated demands by the opposition and civil society groups, however one calculation suggested that only 1 percent of the money went to outlets critical of the government.

The funding controversy, however, points to a much more fundamental failing, and one which has arguably been central to the resurgence of the virus. Funds for the public information campaign were directed overwhelmingly to traditional media, primarily to print, TV and radio, and conventional news sites, a choice that flies in the face of every observed trend in media consumption in Greece, and was therefore destined for failure.

Newspaper readership in Greece has plummeted to below one tenth of 2004 levels according to circulation figures, while the EU’s Eurobarometer survey reveals that only 8 percent of the population say they read a newspaper daily, compared to 53 percent who go online every day. Although internet penetration is a relatively low by European standards at 73 percent, its users increasingly turn to it as their primary source of news. Only a quarter of Greek internet users get their news from print sources, and barely two thirds from TV, according to the Reuters Institute Digital News report. Over 9 in 10 Greek internet users trust the internet as their primary source of news, and 7 in 10 get their news through social media, led by Facebook, YouTube, and various messenger apps. As in most countries in the Reuters survey, social media is twice as popular among younger age groups than are conventional news websites.

By limiting its messaging to the traditional media the government will have failed to reach audiences critical to cultivating a safe environment, post-lockdown, and ones which were already challenging the rules by the final stages of lockdown: the young and the sceptics.

This segmentation of the audience was not as problematic during the hard lockdown phase. The “stay at home” message addressed a captive audience in very unique circumstances. TV spots with a blunt message featuring an instantly recognisable housewives’ favourite addressed one of the main risks at the time - intergenerational mixing - by warning grandparents against the temptation of babysitting their grandchildren when schools closed. The daily briefings delivered by the “good cop, bad cop” team of senior medical advisor Professor Sotiris Tsiodras and head of civil protection Nikos Hardalias became compulsory viewing for housebound families, and developed their own persuasive power.

However, as the government planned for the relaxation of measures it clearly underestimated the challenge ahead. It demonstrated a frustratingly hectoring and tone-deaf approach to dealing with resistance to the rules, and a lack of adaptiveness to the rapidly (but to a great degree predictably) changing circumstances. The failure to stay abreast of social media, in particular, is ironic for a government which prides itself on digital reform and which had only recently trumpeted the appointment of a digital marketing guru to burnish the country’s image.

At the same time, the government’s own actions encouraged complacency among the public at large while continuing to allow the church – a powerful voice in Greece – an extraordinary degree of exceptionalism. The lack of consistency between cautious words and reckless deeds has done its own damage.

Re-opening tourism in itself sent what to many was a conflicting message, signalling that holidaying was not only safe, but to be encouraged, along with all the associated behaviours. Surely there wouldn’t be one set of rules for foreigners and another for locals?

The political class themselves set the first example. No sooner were movement restrictions lifted, than politicians returned to their meet-and-greet schedules with a vengeance. The PM and cabinet ministers vigorously promoted the “back to business” message with visits to shopping districts and other crowded public engagements, while opposition leaders also toured the country to support sectors calling for more economic support. Distancing rules were flouted, hands were shaken, backs patted, babies brandished within an arm’s reach. In many cases only a single mask within a close-packed crowd of dozens dates a photo of a gathering to within the last few weeks. Clergy participating in public events, such as the swearing-in of new cabinet ministers, have been allowed tp appear mask-less despite clear rules mandating the wearing of face coverings indoors.

Also noticeable (or rather not noticeable) in post-lockdown Greece is the almost total absence of visual cues reminding the public of health risks and guidelines. With the exception of scuffed 2-metre spacing guides on supermarket and pharmacy floors (dating back to the days of the lockdown), and inconsistently taped-off seats on public transport, there is barely any indication that distancing guidelines are still in force and that masks are now compulsory in most settings.

Bus stops and billboards still display pre-lockdown advertising rather than any hints to passengers and passers-by of the exceptional circumstances. Signage in parks, playgrounds and sports facilities is still dominated by warnings about littering and dog mess, not distancing.

The failure to engage young people in safe behaviour has gradually dawned on policymakers as the shocking statistics begin to emerge pointing to the increasing prevalence of young carriers, and even seriously ill young people. However, the response has once again followed the conventional path. Over the weekend, Mitsotakis tweeted a slick video warning returning holiday-makers to keep their distance from elderly relatives. The tone was didactic, the messenger not noted for his standing as a youth influencer, and the medium not popular with the under 30s.

Political prism

Any effort at prevention is worth making, even at this late stage. Worryingly, it is not clear that government has fully appreciated the type of exercise required.

While any party in this position would be challenged by the task at hand, it is impossible not to link the catalogue of unforced errors in the government’s response to New Democracy’s political worldview, and its narrow political objectives.

Mitsotakis and New Democracy, having already successfully painted themselves as dynamic reformists in the eyes of much of the foreign media, were eager to claim political credit for flattening the curve. They were also eager to seize on the only economic life raft available to the economically beleagured country by reopening tourism, so as not to be held responsible for job losses and economic hardship in a powerful business sector.

In their rush to hand out public advertising funds to the media establishment, they neglected to keep an eye on the seismic shifts in media consumption which have made them largely irrelevant among the demographics displaying the most challenging behaviours. They soft-pedalled on the church, not wanting to upset the status quo and the centre of gravity of their power base, ignoring the fact that doing so directly undermined the scientific guidance.

Crucially, somewhere along the way it is clear they started to believe their own hype. And as anyone with a passing acquaintance of Greek tragedy knows, hubris is not a precursor to a happy ending.

*You can follow Georgia on Twitter.