-

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

-

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

-

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

-

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

-

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

-

15% Uncertainty: Greece, Europe and the tariff shockwave

15% Uncertainty: Greece, Europe and the tariff shockwave

The case of SYRIZA's fiscal performance

This blog is about the Greek general government overall budget balance since 2013 (after the most difficult phase of the Greek crisis). The Ministry of Finance publishes a detailed excel spreadsheet with monthly data from January 2013 onwards on the operations of the consolidated general government. These monthly data on revenue and expenditure components, and the overall balance and its financing, allow us to calculate the 12-month moving average general government balance. In December, this 12-month moving average indicates the overall balance of the general government for the year as a whole (the annual number).

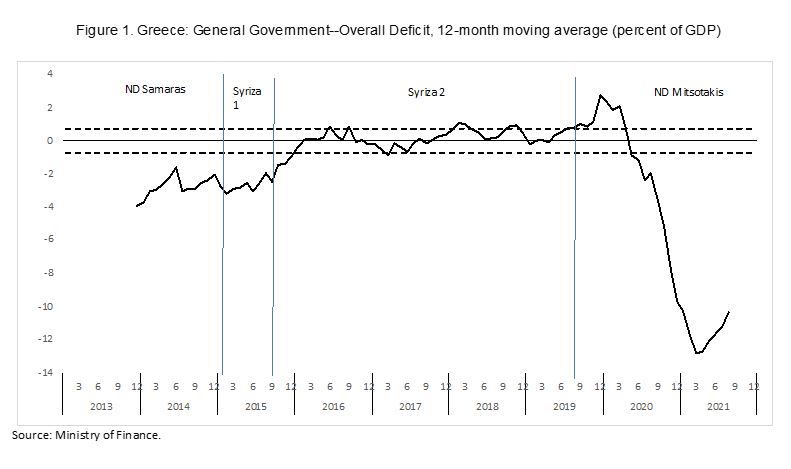

Monthly data are volatile and can jump with leads and lags in revenue and expenditure, and annual data provide only one data point per year, so, instead, calculating a 12-month moving average for each month provides a trend-like picture of what government policy is delivering as regards the overall fiscal balance on an ongoing basis. Figure 1 below shows in the bold line what this 12-month moving average looks like from December 2013 through August 2021.

Figure 1 also shows a dashed line at +0.75 percent of GDP and one at -0.75 percent of GDP. This is done for the following reason: we recommend that Greece follow (roughly) a balanced budget objective. Then a gradual structural return to GDP growth will slowly erode the ratio of debt to GDP. Debt in nominal terms, in euros, would stay constant—consistent with a balanced budget that requires that existing debt be rolled over, and that no new net debt be incurred.[1] To allow for “normal” shocks and noise around the balanced budget objective, which always occur, we have created this indicative symmetrical band of 1.5 percentage points of GDP in width around the balance budget objective. If the government were to aim for a balanced budget, but the 12-month moving average starts traveling outside of the margins of this band, then corrective budget action may be called for, depending on whether the country is subject to a large shock (may not be able to fully adjust in the short term), or to more temporary ups and downs (adjustment would be recommended).

In the light of this easily observed objective (zero overall balance and a stable stock of nominal overall debt), we can now see how government policy has behaved relative to this target. Accordingly, what we see in Figure 1 is that Antonis Samaras’ government through end-2014 ran deficits of between 2-4 percent of GDP. This was inconsistent with a balance budget objective.

The first SYRIZA government (January 2015) of Alexis Tsipras, with Yanis Varoufakis in the Ministry of Finance, broadly continued this trend. The first SYRIZA government, however, was a disaster for Greece in multiple dimensions, not least of which was the efficient destruction by Varoufakis of any trust and cooperation with Greece’s eurozone partners. Many recall the painful episode in which Greece escaped in July 2015 by a whisker the suspension from the eurozone, and the turmoil surrounding the referendum called by Tsipras.

Confused and damaged as the first half of 2015 may have been, Greece survived in the eurozone, accepted the conditions of a new (third) program with the institutions that were stricter than the ones just rejected in the referendum, and Varoufakis was replaced by Euclid Tsakalotos as the new finance minister.

But then, the second SYRIZA government ran fiscal policies as if they had adopted a balanced budget rule. As Figure 1 demonstrates, if one ascribes to the benefits of such a cautious fiscal rule, then the second SYRIZA government must be judged to have run an exemplary budget balance policy, hardly ever traveling outside the confidence band of + or -0.75 percent of GDP away from zero. One can discuss the political or ideological inclinations of SYRIZA, but from a budgetary balance and debt management perspective, this performance was an achievement that few expected after the brief first SYRIZA government. The interesting question is: how did SYRIZA accomplish this and why did they do it?

Before we answer that question, let’s quickly complete the timeline. After SYRIZA lost the general elections in July 2019, the opposition New Democracy party gained an absolute majority in Parliament and formed a single-party government lead by Kyriakos Mitsotakis as premier. At first, the general government budget balance grew above the zero balance band, but then new deficits emerged due to tax cuts and then the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic shock in the economy. Covid-19 is, of course, a very large shock and one that cannot be compensated for in the short run. Consequently, Greece is now far removed from a balanced budget and has incurred substantial additional debt. The risks from very high debt have, if anything, increased, not decreased for Greece.

As noted, the striking path of the general government balance in Figure 1 requires reflection and interpretation. This brings us back to the question what has happened and why, and what might this imply about the potential future success of Greece aiming to emerge at last from the difficult recession in the 2010s? We offer some preliminary thoughts as follows:

- Why did SYRIZA accomplish the turnaround toward good fiscal results? It is quite common for a new government of a different ideological bent to need some time to acquire experience in governing. Therefore many new and inexperienced political parties that come into office tend to have a difficult start. SYRIZA was no exception—the first SYRIZA government was an experiment of ebullience that failed.

- For comparison, and to show that this experience is not unique to Greece, in Western Europe, after the WWII, nearly all governments were of Christian Democratic parties. As the economies recovered from the War, standards of living rose and with it the ambitions and sentiments of labor parties, who had little experience in government. In the 1960s and 1970s the labor parties gradually came into office, favoring a rapid buildout of the social welfare states and heavy doses of demand expansion in a Keynesian way. Their first terms in office were invariably hectic and chaotic, with stagflation in the 1970s as a result. Labor governments then lost power with the Reagan-Thatcher pivot to more conservative governments in the 1980s, and more emphasis on the supply side and productive capacity of the economy. When labor governments got a second turn at governing in the 1990s, many had changed their tune and became more middle of the road parties, with better managerial experiences.

- We interpret the evolution of the second SYRIZA government in a similar light and as a reality check within, but at a very compressed time schedule. The trauma of the first SYRIZA government was such that in July 2015, Tsipras made a 180-degree turn with his EU partners. Now the onus was on Greece to show that it could deliver the mandated fiscal results for several years in order to regain reputational confidence. Between mid-2015 until mid-2019, Tsakalotos as finance minister delivered this requirement—cautious management to keep the primary balance strong (3 percent of GDP surplus on average) and renewed stability in relations with the Euro Group of finance ministers.

- The results were noteworthy: Greece regained footing and was allowed to exit the third program on time in 2018. The economy recovered into a return to new growth. Unemployment started falling as employment started recovering.

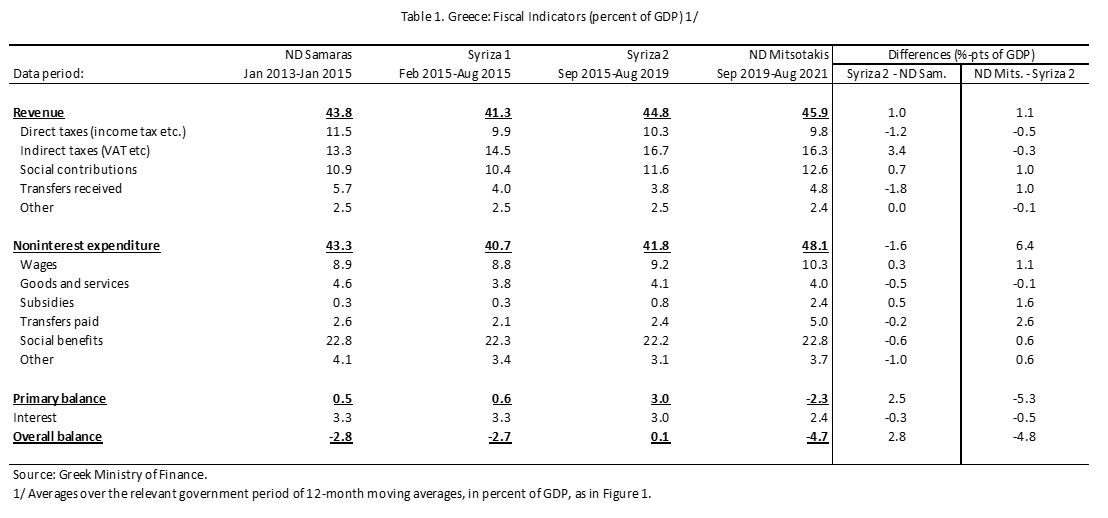

- How did SYRIZA accomplish this? To boost the fiscal balance, SYRIZA 2 increased revenue and cut expenditure relative to the earlier experience under the government of Prime Minister Samaras (see Table 1, 5th column).

- The biggest tax increase was in indirect taxes (VAT etc.). This is remarkable for a left-of-center government because consumption-based taxes put a larger relative burden on lower-income families.[2] Direct income taxes under SYRIZA were lower than under Samaras, and Greece received fewer transfers, including from the EU partners. The latter may have been related to the difficult experience with Varoufakis.

- On the expenditure side, SYRIZA 2 cut spending on goods and services and discretionary outlays (the component “other”), and kept the lid on social transfers.

- As a result, SYRIZA 2 achieved an average overall balance of 0.1 percent of GDP surplus, which is a 2.8 percentage points of GDP improvement on the ND Samaras government.

- In short, the SYRIZA 2 government delivered a remarkable turnaround in the fiscal performance for Greece from mid-2015 to mid-2019. There has been much criticism that SYRIZA was all about tax increases, but the record does not bear this out. At the same time, we do not wish to assert that the SYRIZA party ascribes to a balanced budget objective, because it was forced to recover credibility in short order under much international pressure and very tight financing contraints. In a more relaxed atmosphere and outside of a program with the EU partner countries, we do not know whether SYRIZA would follow a similar budget/debt policy, even though it is remarkable how the economy recovered and how relations with EU partner countries improved once SYRIZA gained credibility with its balanced budget path. But this regained (external) credibility was apparently insufficient to overcome the effects of the internal turmoil from SYRIZA’s inexperience in governing. It was voted out of office in July 2019—just as what happened in the broader European context when the pendulum swung back from firs-time labor parties to more traditional christian democratic parties, after the new labor parties had time to cut their teeth in office.

The experience since the transition of government to New Democracy and Mitsotakis is difficult to assess because the Covid pandemic has been such a huge spanner in the wheels of recovery. Economic advisors of different stripes would have recommended that the government assist the economy in the face of such a large external shock, no matter who is in office. Thus, reading the ND Mitsotakis numbers requires caution. Here are some preliminary observations:

- Both revenue and expenditure were increased substantially and both ratios have hit new records for Greece. In part, this is the result of the cycle—the downturn in GDP. A fuller-fledged analysis at some point in the future should aim to extract the path of revenue and expenditure on a structural underlying basis, i.e. corrected for the cycle.

- ND Mitsotakis has cut both income taxes and indirect (consumption-based) taxes, but it has received higher social contributions (the labor market has held up remarkably well, including due to government support) and transfers (including with assistance during Covid from the EU partners, see column 6 of Table 1 for the change since SYRIZA 2).

- Expenditures have increased even more than revenue, which in part is again due to the recession from Covid. In contrast to what conservative governments often espouse, ND has increased the wage bill, including through a new hiring spurt of civil servants as analysed in Blog 5 of May 2021. The other components with the biggest expenditure increases are subsidies and transfers paid. It is most likely that a large share of these increases are also related to the Covid recession and to offer fiscal assistance to the economy. In all, the primary balance has plummeted by 5.3 percentage points of GDP and the overall balance has sunk by 4.8 percentage points of GDP, on average, after two years of the ND government in office.

- What becomes critical then, is to assess what part of the revenue declines and what part of the spending increases are cyclical (Covid) and what parts are structural (reflecting government philosophy). The ND government has cut taxes structurally because that was part of its electoral platform and philosophy. It is unclear whether this will be earned back as the Covid recession recedes into the background. Cross-country academic research suggests that tax cuts do not pay for themselves in the long run, but they do affect income distribution towards higher-income earners.[3]

- One new element in the mix is that Greece has submitted an ambitious and promising recovery plan to the European Commission, and is set to receive some €33 billion in prospective funding for this plan (the so-called NextGenerationEU).

- Thus, it is almost guaranteed that spending in the economy will increase because external funding transfers are available, as in a classic Keynesian boost to the recovery. But what counts is whether the ND government can avoid translating this unprecedented volume of spending capacity into more consumption (Greece already runs permanent current account deficits). Rather, what is needed is investment in productive capacity so that the economy proves robust in the future on the supply side to continue the upswing without generating new disequilibria.

- To get a sense of this future, the government promises to deliver a primary surplus of 3.7 percent of GDP by 2025. This would restore the overall balance close to zero—close to a balanced overall budget. But in its recent outlook for the Greek economy, the IMF is concerned that current measures and those envisaged already in the pipeline will only deliver a primary surplus of 1.5 percent of GDP in 2026. If that were to be the case, then the tax cuts and expenditure management will have had structural deficitary implications, preventing Greece from reaching a balance budget and stability in the nominal stock of debt.

- For now, it is still too early to be able to differentiate in a decisive way between the two alternative expectations for the future.

In the next blog, for December 2021, we will take the ideas about the general government balance and debt, and during different government periods, one step further. We will discuss why even a balanced budget result does not always imply that the debt will stabilise.

*Bob Traa is a macroeconomist and author of "The Macroeconomy of Greece: Odysseus' Plan for the Long Journey Back to Debt Sustainability" published in 2020. Jens Bastian is senior policy advisor at ELIAMEP.

[1] For a detailed rationale behind this recommendation of a balanced budget in the case of Greece, see the book: Bob Traa “το σχέδιο του Οδυσσέα” (Economia Publishing, 2019), or its equivalent in English: Bob Traa “The Macroeconomy of Greece” (Amazon.com 2020).

[2] In Blog 10 (October 2021) we demonstrated that the primary income component “indirect taxes minus subsidies” in the National Accounts accruing to government had increased remarkably under the SYRIZA government.

[3] See for instance, the paper, published by LSE’s International Inequalities Institute: The Economic Consequences of Major Tax Cuts for the Rich, by David Hope and Julian Limberg (December 2020), which demonstrates that the last 50 years were a period of falling taxes on the rich in the advanced economies. The paper states that: “Our results show that…major tax cuts for the rich increase the top 1% share of pre-tax national income in the years following the reform. The magnitude of the effect is sizeable; on average, each major reform leads to a rise in top 1% share of pre-tax national income of 0.8 percentage points. The results also show that economic performance, as measured by real GDP per capita and the unemployment rate, is not significantly affected by major tax cuts for the rich. The estimated effects for these variables are statistically indistinguishable from zero.”