-

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

-

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

-

15% Uncertainty: Greece, Europe and the tariff shockwave

15% Uncertainty: Greece, Europe and the tariff shockwave

-

Summit of transactions – Erdogan and Trump

Summit of transactions – Erdogan and Trump

-

Podcast - DETH and taxes: The only things certain in Greek politics

Podcast - DETH and taxes: The only things certain in Greek politics

-

How will Trump's tariffs affect Greece?

How will Trump's tariffs affect Greece?

Does the EU Commission suffer from optimism bias? (Part 2)

In the previous blog we expressed concern that the European Commission may suffer from an optimism bias. We noted that the long-run outlook for real GDP growth in the EU27 as a whole appeared to be based on too-favorable labor productivity growth assumptions.

The Commission’s Reports explain that the long-run productivity outlook is based on a notion of “convergence.” This posits that past underperforming member states will experience future productivity growth well in excess of the better performing member states. Future average EU27 productivity growth per employed person a year thus jumps from 0.7 percent in 2000-2020 to 1.6 percent in 2021-2070—an increase of 129 percent (!) in productivity growth. This “leveling up” assumption in productivity growth drives the optimistic EU real GDP outlook.

We also suggested that this aspirational assumption, leading to an aspirational real GDP growth outlook, should not be called a “baseline,” because the conventional use of the term “baseline” reflects a maximum likelihood scenario, not an aspirational, or optimistic, scenario.

Presenting an aspirational growth scenario as the baseline in official EU documents carries risks. It risks that member states (strategically) adopt this scenario as their own (for which there is evidence[2]). The debt that gets placed to deliver such a high growth scenario will likely come, but the high growth rate itself may not come. Indeed, it is unlikely to come. This is the specter of a debt ratchet, based on overoptimistic assumptions. Regrettably, this problem is common.

* * *

In his book “Thinking, Fast and Slow,” the psychologist Daniel Kahneman explains that human beings are often “not rational” as in the conventional rationality assumptions used in explaining economic behaviors. Instead, he notes that our first responses to stimuli are often heuristic and superficial. This is System 1, or “Fast Thinking,” based on instincts and emotion. System 1 has evolved for survival and immediate coping, but it is somewhat lazy and often inaccurate. Instead, our deeper understanding of matters emerges when we take the added effort to turn on System 2, or “Slow Thinking,” based on analysis and contemplation.

As a result of this predominant “Fast Thinking” which is often inaccurate, Mr. Kahneman shows that many inaccuracies reflect “biases” or shortcuts that are convenient, but are often misleading upon deeper reflection in “Slow Thinking.” Mr. Kahneman lists a whole host of “biases” that he, and his collaborator in psychology research Amos Tversky, have uncovered over the years. Their academic papers on this topic have created a theory of where we often go off the rails in our “rationality” assumptions called “Prospect Theory.”[3]

In chapter 23 of his book, called “The Outside View,” Mr. Kahneman explains the “optimism bias.” The optimism bias is prevalent in groups that constitute “The Inside View,” or, to paraphrase the message of the book—excessive optimism in baselines prepared by those who have skin in the game with regard to the outcome. (The European Commission and its political backing have skin in the game when endeavoring to achieve convergence in the EU27.) Mr. Kahneman is quite assertive when he writes that:

“…the optimistic bias is a significant source of risk taking… When forecasting the outcomes of risky projects, executives too easily fall victim to the planning fallacy. In its grip, they make decisions based on delusional optimism rather than on a rational weighting of gains, losses, and probabilities. They overestimate benefits and underestimate costs. They spin scenarios of success while overlooking the potential for mistakes and miscalculations”

(Thinking, Fast and Slow, page 252)

Mr. Kahneman also explains that such biases are entirely human and normal. He notes that organizations best avoid them by being aware and doing something about it. In chapter 24 called “The Engine of Capitalism,” he discusses what could be done (“A Partial Remedy”) to guard against overconfidence and optimism bias:

“…the premortem.…gathering for a brief session a group of individuals who are knowledgeable about the decision. …Imagine that we are a year into the future. We implemented the plan as it now exists. The outcome was a disaster. Please take 5 to 10 minutes to write a brief history of that disaster.”

“The premortem has two advantages: it overcomes the groupthink that affects many teams once a decision appears to have been made, and it unleashes the imagination of knowledgeable individuals in a much-needed direction.”

(Thinking, Fast and Slow, pages 264-5)

There is no doubt that the convergence assumptions in the baseline scenarios of the European Commission carry the best intentions for the people of Europe. But, is there an optimism bias, and is this risky? Should independent outsiders, familiar with the material, do a more systematic evaluation of such outlooks, before these are printed and distributed? At the least, one would propose to call the central scenario an “aspirational scenario” and not a “baseline scenario,” because it is not.

Making optimistic scenarios is more common than you may think. One of the authors of these blogs has spent over 33 years in the International Monetary Fund in country work, helping countries with IMF programs, calibrating baseline scenarios. In many countries, the Ministry of Finance (more so) and the Central Bank (less so) would first propose a baseline scenario that is too optimistic—governments have skin in the game to talk things up.

The pressures are so high on Fund staff, that, on occasion, IMF teams “go native” and accept, at least in part, these overly optimistic assumptions. Nearly always, this results in problems of programs going “off track.” The institutional vaccine in the IMF (and other international institutions, including the European Commission) now has become the euphemistic phrase that “the risks are slanted to the downside,” that routinely shows up in the risk section of economic country reports. More often than not, when you see this, the reader may assume that the true baseline sits several degrees below the indicated one.

We are all human and we all want to root for the best possible outcome, just as Mr. Kahneman predicts, based on his pathbreaking psychology research. Adopting more moderate, and more risk-averse and realistic, scenarios as the baseline is often not politically popular, and in electoral cycles can be politically suicidal. There is no easy solution.

* * *

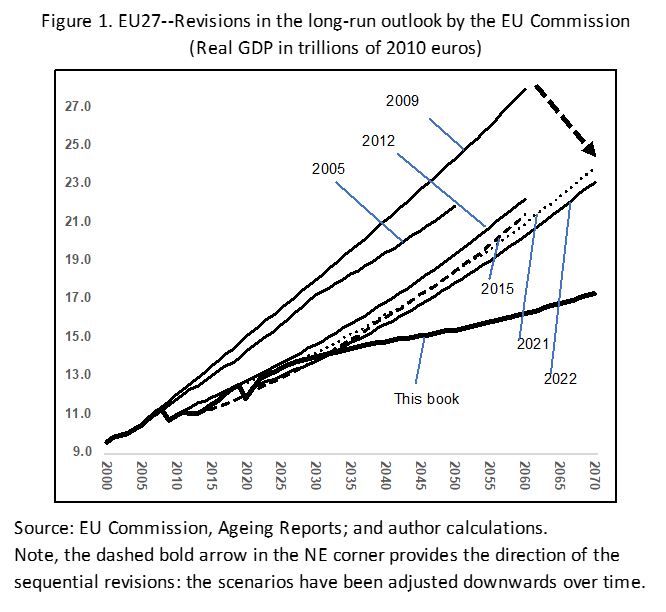

EU Commission Scenario Revisions

The EC staff updates its real GDP long-run scenarios in subsequent Reports. What we would expect is that, if there is an optimism bias, then the subsequent revisions will likely be revised downwards over time. Figure 1 is a plot of five sequential long-run EC real GDP outlooks presented in the aging reports (assumptions etc.). The 2022 line shows the same growth rates as in the 2021 Ageing Report, with updated EU Spring Forecasts for 2022. For comparison, the line “This book” shows the baseline as calculated in the Book on the Macroeconomy of the European Union, referenced in footnote 1.

We see, in general, that EU Commission revisions have been downward, as indicated by the dashed arrow in the NE corner. The 2005 baseline scenario did not anticipate the Great Recession, nor the Covid-19 pandemic, but was influenced by a few difficult years in the early 2000s, coming off the dot-com collapse. Then, the 2009 baseline was lifted up, because growth in the previous years was buoyant (and unsustainable, as the Great Recession of 2009-2010 would show). This suggests also some pro-cyclicality in the forecasts.[4]

More recently, the EC “baseline” scenario has moderated further, but is still not nearly as moderate as the baseline in the new Book on the Macroeconomy of the European Union. Of course, the Ukraine War was not foreseen, but no shock in the future is ever foreseen. Shocks will always happen, even if we don’t know what they will look like. The EC Ageing Reports’ macroeconomic framework frequently looks too optimistic, as consistent with an optimism bias in the spirit of Mr. Kahneman’s research.

*Bob Traa is a macroeconomist and author of "The Macroeconomy of Greece: Odysseus' Plan for the Long Journey Back to Debt Sustainability" published in 2020. Jens Bastian is senior policy advisor at ELIAMEP.

This second Blog on the “optimism bias” is an adapted extract from Chapter 8 of a new book by Bob Traa on “The Macroeconomy of the European Union: A Work in Progress” (in this blog text referred to as “the Book”).

[2] For example, in the 2022 Stability Report submitted by the Greek government to the European Commission for assessment of Greece’s fiscal plans, the Greek government “adopts” the long-run macroeconomic outlook as calculated by the European Commission in its Ageing Report. It does not present its own view.

[3] The findings of these deviations from rationality were so important that Mr. Kahneman received the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences in 2002 (Mr. Tversky had passed away before the Nobel Prize was awarded).

[4] Linear extensions from previous years are common in forecasts. Cautious forecasts see through the ups and downs of the cycle.