-

Podcast - Kaisariani photos: Why Greece’s past is present

Podcast - Kaisariani photos: Why Greece’s past is present

-

Is the Greek green transition running out of power?

Is the Greek green transition running out of power?

-

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

-

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

-

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

-

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

Does the EU Commission suffer from optimism bias? (Part 1)

This blog post is based on Chapter 8 of a new book: “The Macroeconomy of the European Union,” by Bob Traa, available on Amazon.com. The book examines structural considerations for potential growth, fiscal and debt developments, and the fiscal rules in the EU27 and in each individual member state, including Greece.

The EU Commission (EC) conducts regular surveillance over economic policies in the EU. In this capacity, the EC staff updates its view of the macroeconomic outlook (population, employment, unemployment, productivity, real and nominal GDP projections/scenarios), alongside monitoring and providing surveillance of fiscal and public debt developments in the member states and for the EU27 as well as the Euro Area as a whole.

We may mention in particular three helpful and detailed reports the EC produces on a regular basis: the Ageing Reports and the Fiscal and Debt Sustainability Reports.

“European Economy Institutional Papers are important reports analyzing the economic situation and economic developments prepared by the European Commission's Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs, which serve to underpin economic policy-making by the European Commission, the Council of the European Union and the European Parliament”

(from the introduction to the Reports)

These insightful Reports assess developments in population dynamics and aging of the population, and what this means for cost components in EU fiscal developments, including pension spending, welfare assistance, unemployment benefits, health, and education—all sensitive to demographic developments.

We will compare the macroeconomic scenarios as presented in the 2021 Aging Report (Assumptions and Methodology) with the findings in the new Book on the macroeconomy of the European Union, noted above (the Book). In part 1 of this blog we will highlight differences in the macroeconomic scenarios and why these differences are important for policy interpretation. In part 2 of this blog, we will call on Daniel Kahneman’s important book “Thinking, Fast, and Slow” to suggest that the EC may suffer from the “optimism bias,” which tends to lead the Brussels institution to making forecasts about potential growth that are too generous. This, in turn, imparts an excess debt bias, putting pressure on the Maastricht deficit and debt Criteria.

* * *

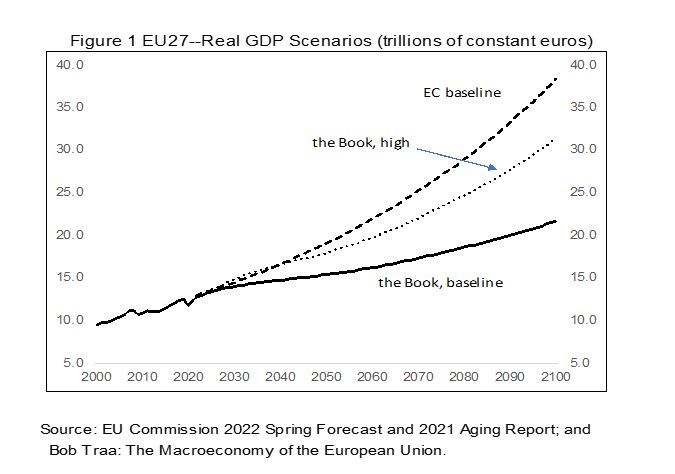

Figure 1 below compares the baseline scenario in the EC 2021 Ageing Report with two real GDP scenarios in the Book. The differences are somewhat startling. The EC growth outlook in its “baseline” scenario is higher than the “high” or optimistic scenario that was derived in preceding chapters of the Book.[1] The baseline scenario of the Book is well below the EC baseline scenario. In the EC baseline scenario, by 2100, real GDP of the EU27 would approach almost double (nearly €40 trillion) that of the baseline scenario in the new Book (€23 trillion)—this finding is significant.

“Annual potential GDP growth in the EU is projected to average 1.3% over the period 2019-70 under the baseline scenario. It will average 1.2% up to 2030, rising slightly to 1.3% during 2031-40 and to 1.4% in the 2040s. It is then expected to remain at this level up to 2070.”

(2021 Ageing Report, part 1, page 66)

The question arises where this stark difference in the baseline scenarios comes from? We can look at the components of real GDP to understand the reason.

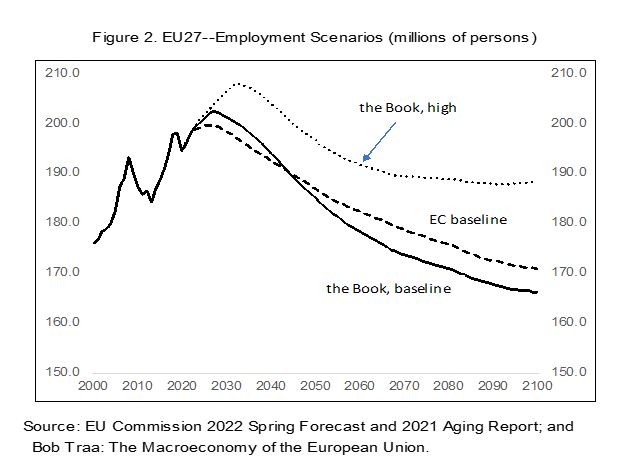

Real GDP is the product of labor input and average labor productivity (Q = L *(Q/L)). Figure 2 shows the scenarios for labor input in the EC Report and the new Book. The EC staff uses demographic projections from Eurostat. The Book uses the same projections:

“Labour input projections are based on assumptions taken from Eurostat's latest population projections.”

(2021 Ageing Report, part 1, page 66)

Thus, the population outlook is the same and cannot explain the difference in the macroeconomic outlook. Despite some differences in phasing over time, the baseline scenarios for employment in the EU27 are not significantly different in the Figure above. The new Book has a slightly more extended rebound in employment shortly after the Covid shock to the EU economy than foreseen by the EC, and somewhat lower employment later on. But the demographic anchor exerts itself in both baselines, eventually reducing the employment potential of the economy (and hence slowing growth).

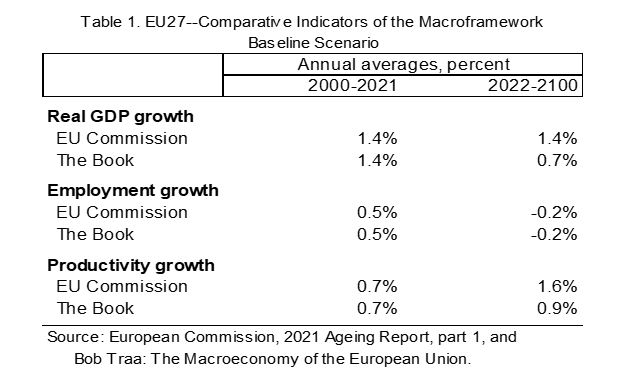

The small difference in the level of employment toward 2100 is not large enough to explain the sustained higher level of real GDP found in the EC baseline presented in Figure 1. The average annual growth rate in labor input between 2022-2100 in the EC scenario and in the Book are the same: -0.2 percent a year through 2100 (see Table 1, below).

We may also point out that the “high” growth scenario in the Book, compared to the baseline scenario, is the result of higher participation, lower structural unemployment, and a bigger labor force, hence delivering higher employment throughout the future years (Figure 2). But, even with this sustained higher level of employment, the “high” real GDP scenario of the Book in Figure 1 does not match the “baseline” real GDP scenario of the EC.

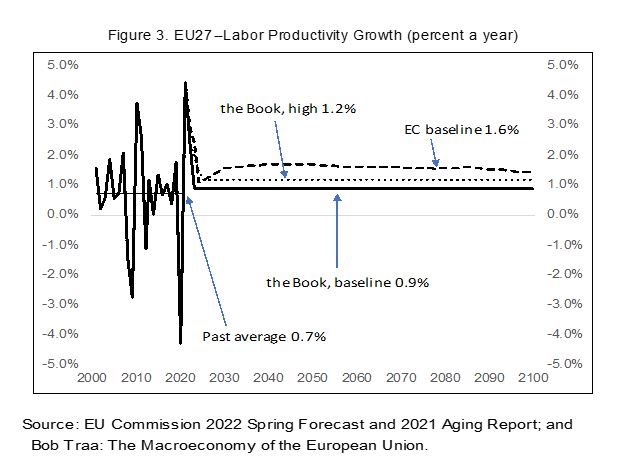

Thus, the key difference between the scenarios in the new Book and the EC must reside in assumptions about future productivity. Figure 3 summarizes these results in a comparative way. We show the growth rates in productivity in the baseline of the EC and the Book, the growth rate in the “high” scenario of the Book, and average growth in the period 2000-2021.

The baseline growth rate in average labor productivity derived in the Book is 0.9 percent a year (solid line), an improvement from 0.7 percent a year over the past two decades. In the optimistic “high” growth scenario (dotted line), the average productivity growth rate is 1.2 percent a year; an improvement from past performance by over 50 percent. We now also see that the EC assumes that the EU27 growth rate in average labor productivity going forward will more than double to 1.6 percent a year (dashed line). This is the critical difference in assumptions in the two respective models and scenarios for the prospective macroeconomic outlook. How does the EC come to this productivity assumption? The Ageing Report notes:

“The long-run projection is based on the central assumption of convergence of all Member States towards the same value of labour productivity by the end of the projection horizon.”

(2021 Ageing Report, part 1, page 66)

The end of the Report’s projection horizon is 2070. All member states that start with lower-than-average labor productivity see a burst in labor productivity growth through 2070 to catch up to the average level of labor productivity by that date. It is not assumed that the most productive member states falter and lower the average. No, the poor performers all are lifted, by assumption, to a level in 2070 that is much higher than they have delivered in the past.

This “averaging up to convergence” (or “leveling up”) of labor productivity performance is a critical step in the EC baseline projections. Thus, we see in the EC Report that, for example, Greece, which has been struggling with average productivity growth around zero, is assumed, by statistical construction, to reach productivity growth of 2.2 percent a year by 2040, 2.0 percent through 2050, 1.8 percent through 2060, and 1.5 percent a year through 2070.

Other countries, such as Bulgaria, Czechia, Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, Romania, Poland, Slovakia, and Hungary, are imputed with even more remarkable upswings in productivity growth (to above 2 percent a year on average). These “recoveries” are mathematical artifacts based on the need to reach convergence by 2070 from a below-average level. They are not based on a “most likely” interpretation of the political-economic environment and policies of these countries.

What the EC presents is not a “baseline” in the conventional way, but rather it imputes an “aspirational” assumption of convergence into the model. In turn, this pressure to use aspirational assumptions is political—the number is a political objective, with the hope that countries that have performed poorly in the past, with the right encouragement and sufficient structural reform and money from the political machinery of the EU, would be poised to achieve full convergence in their growth rates to the better performing member states.

There is nothing wrong with expressing aspirations for member states that have had lagging productivity and competitiveness in the past, but the Book questions whether it is a good idea to build this into the model as a “baseline.”

From a risk perspective, the probability that, with this modeling strategy, the future will disappoint is high. The bias is not innocent. Local member states use the baseline projections from the EC to justify higher spending in their budgets (because, according to the EC, the surveillance agency for fiscal performance and debt, the economy is poised to grow out of the resulting debt financing).

This juxtaposition also generates pressures for mutualizing debt. If the EC forecasts such high potential growth rates with the right investment and policy support, then the wealthier EU27 countries will surely want to help finance this good future performance. There is no-one in the EU27 who is against “convergence” after all.

By approving the “aspirational” scenario as a “baseline” for all EU countries, all member states express their commitment to this aspirational scenario as a political objective, and therefore must be understood to be willing to help finance it as well. This constitutes a circular argument from a “baseline” to an “aspirational” scenario, which then becomes the “aspirational baseline” scenario. But, this is something quite different from a “maximum likelihood” scenario, as is the conventional understanding of a “baseline.”

From a risk perspective, the “aspirational baseline” invites debt problems. By saying that countries will converge to a relatively high growth rate, and thus giving a green light to raising debt accordingly, the probability that the debt will grow faster than actual GDP is high: the debt will be incurred, but the elevated growth rates may not come.

Countries that get into debt problems will then go back to the Commission and say that they have done what the Commission has calculated and what the member countries have approved. This then becomes the argument that accountability for the results must therefore be at least partially born by the membership as a whole, via debt restructurings at favorable terms for the overindebted countries. After all, they have based their policies on what the Commission has projected for them and what the Council of Ministers has approved.

The results in the EU show this risk pattern. The Stability and Growth Pact, governing the Maastricht fiscal and debt rules, was to limit debt ratios in the EU to sustainable levels (<60 percent of GDP). But shocks have come and growth has disappointed. The aspirational assumptions have not worked out so far. The result is that the debt is not at 60 percent of GDP or less, but rather for many countries closer to 100+ percent of GDP and rising.

“…potential GDP growth in the EU and the euro area will be driven almost entirely by labour productivity. Annual growth in labour productivity per hour worked is projected to increase in the period to the 2030s from less than 1% to 1.5% and to remain fairly stable at around 1.6% thereafter throughout the remaining projection period. As a result, the average annual [labor productivity] growth rate is projected to be equal to 1.6% throughout the projection period (2019-2070).”

(2021 Ageing Report, part 1, page 70)

* * *

In Part 2 of this Blog, we will draw on the psychological research of Prof. Kahneman in his book “Thinking, Fast and Slow,” to note that “optimism bias” in economic projections is quite common. This optimism bias is best avoided because it can lead to significant problems, including, as we have argued above, a debt bias.

*Bob Traa is a macroeconomist and author of "The Macroeconomy of Greece: Odysseus' Plan for the Long Journey Back to Debt Sustainability" published in 2020. Jens Bastian is senior policy advisor at ELIAMEP.

[1] The Ageing Report’s horizon is 2070. This was extended through 2100 with constant rates of change from 2070.