-

Is the Greek green transition running out of power?

Is the Greek green transition running out of power?

-

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

-

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

-

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

-

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

-

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

Tormenting Greece with a distorted picture

Greece is experiencing one of its regular bouts of schizophrenia, when its mood swings wildly, what it wants changes abruptly and what is considered good one day can become bad overnight.

The stress of reaching an agreement with the country’s lenders, thereby ensuring more funding, staving off a default and securing Greece’s place in the eurozone is the trigger for these manic episodes. The picture of confusion and panic is exacerbated by the contamination of the public debate through intentional efforts to mislead or misguided attempts to analyse a complex situation.

One of the prime examples of the split personality syndrome that kicks in at moments like the current one, when Athens and the institutions are locked in talks to conclude the latest programme review, is that until the agreement at the February 20 Eurogroup for the lenders to come back to Greece, opposition politicians and some local commentators were screaming at the government for supposedly delaying the review’s conclusion. Once the government secured the return of the creditors by agreeing to legislate new cuts to the tax-free threshold and pensions, many of the people who had previously been shouting to the rafters about foot-dragging in Athens, began to blast the coalition for accepting new measures.

They rightfully questioned the government’s claims that the era of austerity was coming to an end but also suggested that the coalition had somehow voluntarily agreed to a new round of avoidable cuts to conclude the review. Once the lenders made it clear that the immediate legislation of new fiscal measures worth around 2 percent of GDP was a prerequisite for concluding the review, Athens had little choice but to acquiesce.

Could this have been avoided if the review had been wrapped up earlier? This is valid point for discussion but it should be noted that there is nothing new or rare about a Greek programme review dragging on. In its recent publications on Greece, the International Monetary Fund underlined that only five of 16 programme review have been completed since March 2012. Also, the IMF indicated last summer, when the government concluded its first review that it would not drop its demands for pension and tax reform from Greece and debt relief from the eurozone. Perhaps both sides felt that another fudge would ensue but the Fund has so far made it clear it will not accept any messy compromises.

This is primarily what has caused the review to be prolonged. This is primarily what has caused the review to be prolonged. We shouldn’t forget that since the December 5 Eurogroup, the IMF and the European lenders have been crossing swords about Greece in public, via blogs and op-eds. Until now, there has been no basis for an agreement between the various parties, regardless of any procrastination in Athens. It is also worth noting that while the new fiscal measures demanded by the Fund are being discussed in Athens at the moment, there have been no such negotiations so far over the debt relief requested by the IMF.

Another good example of the schizophrenia gripping Greece is that having launched attacks on the government for not concluding the review and then accepting more measures to conclude it, opposition parties (which have said they will not support the new round of cuts) have gone back to blaming the coalition for allowing uncertainty to creep back in and undermine the economy.

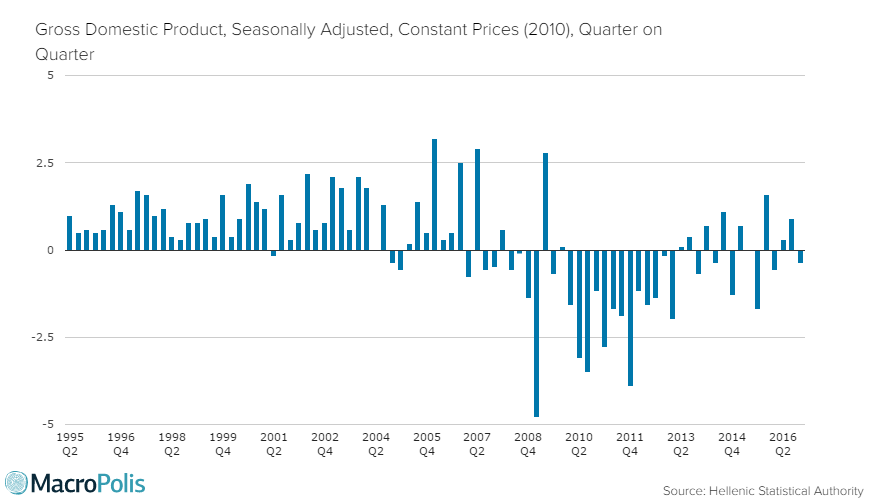

Uncertainty is nothing new in crisis-era Greece. It has always been the big killer for the Greek economy, keeping local businesses from expanding, scaring away foreign investors and undermining any long-term planning. Like a seasonal virus, it strikes and leaves havoc in its wake.There are undoubted signs that confidence in Greece has been shaken over the last few months due to concerns about when or whether the review will be concluded: Q4 2016 GDP contracted by 0.4 percent after growing in the two previous quarters, while manufacturing PMI has been in contraction territory for the last six months and economic sentiment fell by 2.2 percent in February.

Greece will never be able to truly rid itself of this virus until there is a comprehensive agreement that lifts it out of the crisis and convinces markets, investors and the local population that the country has been placed on an irreversible path to recovery. Until then, uncertainty will linger. The question is what actions the government and others can take to limit it until this breakthrough arrives.

The coalition has not been good at this. In fact, it has often found ways to make the situation worse. Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras’s decision to use some of the excess 2016 primary surplus to grant 1.6 million pensioners a Christmas bonus polarised the discussion with the lenders, while comments from SYRIZA’s parliamentary spokesman Nikos Xydakis about the need for a debate about the drachma fuelled Grexit speculation.

However, the government has not been the only one making such missteps. New Democracy leader Kyriakos Mitsotakis recently spoke in Parliament of a Grexit threat, before going to Berlin a few weeks later and insisting that Greece’s place is in the eurozone. His party has also been blamed for cultivating press stories about an imminent referendum on euro membership.

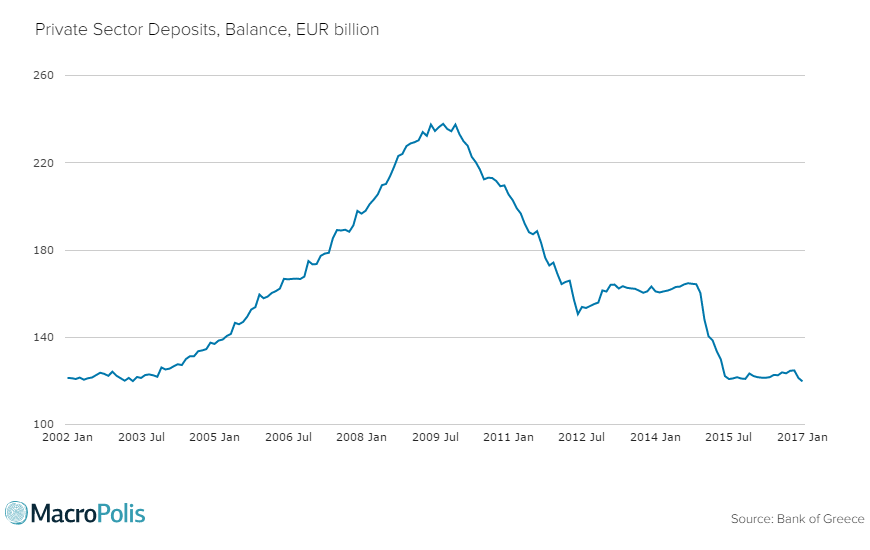

Deposits

The local media has also been running stories for the past few weeks about a large outflow of deposits from Greek banks, another sign of uncertainty taking grip. The problem with these stories is that they become self-fulfilling prophecies: People hear about others taking money out and then feel their savings are in danger so they also withdraw cash (to the extent that capital controls allow them).

The other problem with the recent stories is that once the Bank of Greece published its data for the state of deposits in January, the actual picture was less dramatic than had been suggested. There was an outflow of 1.53 billion euros in January but the first month of the year has traditionally seen deposits fall. In January 2015, for instance, there was a 1.12-billion-euro outflow. The 400-million-euro increase in the outflow compared to a year earlier is a warning sign but not a cause for panic at this stage.

Equally, the failure of some journalists and commentators to note that there had been a change in the way the Bank of Greece recorded deposits led to several reports claiming that the overall figure had dropped to its lowest since 2001. The central bank noted in December that it was reclassifying 6.3 billion euros of deposits from private to general government, meaning the total could no longer be directly compared with previous ones.

If these 6.3 billion euros are added to January’s total, it comes to 126.05 billion, which is the second-highest figure since May 2015. Clearly, this gives the latest data a different complexion.

Greece is in a difficult enough position as it is without people being presented with a distorted picture caused by a lack of knowledge or driven by concern for political gains. By compounding Greeks’ anxiety in this manner, unnecessary torment is being inflicted on the country and its people.