-

Is the Greek green transition running out of power?

Is the Greek green transition running out of power?

-

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

-

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

-

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

-

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

-

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

Greece - On the importance of productivity growth

In early January, Macropolis published a blog from our hand that discussed the importance of demographics for the future of Greece and the Greek economy. Demographics are important for the overall size of the economy. More people tends to translate into bigger economies, and this can influence the scope for sustainable fiscal deficits and public debt.

We also noted that simply having more or less citizens in the country says nothing about the economic wellbeing of the population. To assess the latter, different indicators are needed, such as productivity per worker and real GDP per capita, the distribution of income, and notions of fairness, honesty, and opportunity for all citizens alike. Seen through this wider lens, we noted that some very small countries (e.g. Luxembourg) have much higher standards of living than the bigger countries in the world.

In this blog, we look at productivity developments and their link to real GDP per capita. Our motivation is guided by an observation associated with realpolitik. The absolute size of economies cannot be measured only in terms of GDP volume. Its size is also a political concept. Elected leaders don’t necessarily focus on per-capita income. Instead, politicians care about the importance of the influence an economy’s size has on political sentiment. In realpolitik they feel more important as they govern more people and bigger economies. By contrast the economic (welfare) concept focuses on how well citizens are doing, per person, on average.

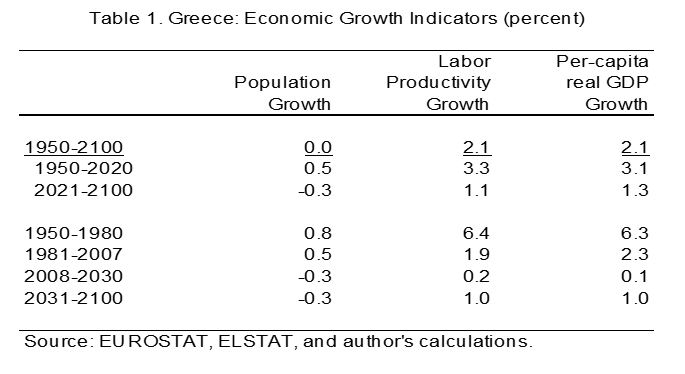

Table 1 presents key statistics to support our bearings. The population data come from EUROSTAT and represent the 2020 “central” scenario for expected population growth in Greece through 2100. The data start in 1950 with almost 8 million Greeks, growing to 11 million in 2011, before declining gradually to around 8 million by 2100 (at which point it is expected to stabilize). This means that in the past seven decades (1950-2020) the Greek population grew on average by 0.5 percent a year. In the future eight decades (2021-2100) it is expected to decline by 0.3 percent a year (Eurostat’s baseline projection).

From a political point of view, the projected decline in the Greek population coupled with higher life expectancy should be a significant matter of attention. Over time a declining population leads to a shrinking labor force. Internally, population decline can generate political and institutional stress. It is easier to manage a country when real GDP growth lubricates the wheels and makes it easier to provide a better standard of living for all citizens. When economies slow down or even decline and the population shrinks, distributional issues can become acutely political, which can be a real policy challenge. Better to acknowledge its possible implications sooner – e.g., for inter-generational equity - rather than later.

From an economic point of view, the situation is somewhat different. Smaller countries can do very well in achieving a high standard of living. That depends not on the volume of life (the size of the population), but rather on the quality of life (the effectiveness of politics, including in the organization and education of society). In the long run, these issues come together in determining the productivity of the economy. Productivity is the most important determinant of the standard of living, i.e., how efficient and effective is each active worker in the economy in producing real GDP? Moreover, if a population declines and the labor force shrinks then lasting income growth can only come from productivity growth. Average labor productivity can be measured as real GDP divided by the number of workers, or “labor,” that produced this real GDP.

Our table shows that in the past, labor productivity in Greece grew by 3.3 percent a year on average, with a heavy weight for the earlier years when Greece was rebuilding from WWII. In the 1980s, productivity growth dropped significantly. This was in part the result of the jump in international oil prices. The monetary cost of energy input in economies increased dramatically from the 1970s onwards.[1] All industrial countries show this pattern. This development is not particular to Greece. The significant difficulties with productivity growth in Greece arrived during the euro crisis of 2008-2015, as the country had to restructure following the overvaluation of competitiveness and labor costs. Gradually the realization sunk in among decision makers and citizens that structural reforms were overdue to lift efficiency in the economy.

The underlying structural developments in the Greek economy have now stabilized, and the expectation is that productivity growth will recover as the country emerges from the current disruption of COVID-19. By how much productivity growth may recover is anyone’s guess. Most countries show baseline scenarios for the longer run outlook of productivity growth recovering to around 1 percent a year. We also accept this assumption for Greece. [2]

The structural reforms that are advocated by the Mitsotakis government on the basis of the 2020 Pissarides Report also aim at achieving higher productivity rates. Together with the financial assistance from the EU in the Recovery and Resilience Facility, productivity numbers should remain at the center of our radar screen as events unfold in 2021 and beyond.

On the basis of this line of thought we can turn our attention from productivity per worker to the concept of real GDP per capita. About half of the Greek population is employed in work to produce the real GDP. So, we need to translate the real GDP per worker into real GDP per person by dividing overall real GDP by the population, instead of by labor. Roughly speaking, the level of real GDP per person is about half of productivity per worker.

When we look at the growth rate of real GDP per person, we can see that this closely follows the growth rate of productivity. That is why productivity growth is so crucial for a society’s wellbeing. If the population grows a bit faster than employment, the growth rate of real GDP per capita will be slightly less than the growth rate of productivity per worker, as happened during 1950-2020, on average. In the future, the population is expected to decline slightly faster than the number of workers. This reading is supported by assumptions that participation in the labor process can be increased, e.g., among women and the elderly (even in declining demographics). This interaction causes productivity growth to lag slightly behind growth in per capita real GDP.

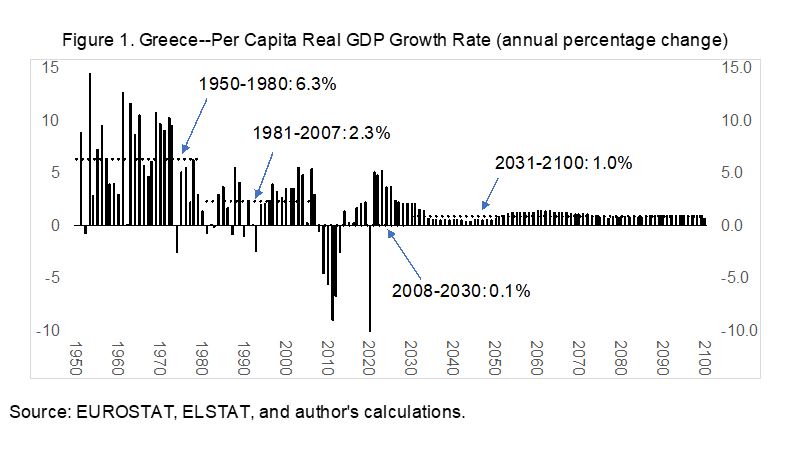

Figure 1 shows what the annual growth rates in real GDP per capita have been since 1950 in Greece, and what they are expected to be, on average, through 2100. The averages for the important sub-periods are also shown, demonstrating the difficult crisis that Greece is emerging from. The figure shows that the COVID-19 downturn in 2020 is severe (in GDP per capita terms), but we argue that it is a transitory effect, followed by catching up effects during the rest of the decade. As such, the structural recession of the 2010s was much more problematic for Greece than is now expected for the COVID-19 recession. Put otherwise, the pandemic is not taking place in a historic vacuum. Comparisons with the crisis of the previous decade suggests that this time the downturn will be much shorter lived.

This interlinkage has crucial implications for policy making in Greece. The constraints we have identified, both in terms of population growth, productivity and per-capita potential growth need to be translated into the expectations of political leaders and thoroughly discussed with society. If policies and budgets are calibrated on expected growth rates that are higher than potential, then Greece risks getting into a new competitiveness and debt crisis.

Thus, assisting the economy towards a new growth path should not be based on inflationary policies that exceed the ability of the economy to deliver. Debt expansion as is occurring during the Covid-19 pandemic should be temporary and conditional, e.g., by issuing sovereign bonds for targeted projects (research & development, addressing climate change, transport infrastructure and the focus on health economics). It is correct under the present circumstances to avoid tax increases and refrain from spending cuts.

But in the medium-term the fiscal repair job will have to start. As Greece’s 2020 preliminary central government finances illustrate, the overall balance, including the cost of the pandemic, showed a deficit of 22.8 billion euros. And the primary deficit was 18.2 billion euros, instead of an original target of a surplus of 3.5 billion euros. Once budgetary support to help bridge the COVID-19 challenge is no longer necessary, Greece should return to a balanced overall budget, and then use complementary reforms and well-calibrated tax and expenditure policies to drive productivity increases, and thus real GDP growth.

In our view, and given moderate future growth conditions and constraints, governing with a balanced budget is the key challenge for the Greek political system. Interest rates will not stay as low as they are today when the recovery begins. Voters can easily check whether the political system can offer a reassuring dialogue with the public, convince with structural reforms, while maintaining a balanced budget on average. The discussion about a new framework for fiscal policy is starting to emerge in Athens.

*Bob Traa is a macroeconomist and author of "The Macroeconomy of Greece: Odysseus' Plan for the Long Journey Back to Debt Sustainability" published in 2020. Jens Bastian is senior policy advisor at ELIAMEP.

[1] We acknowledge that the costs of climate change are not included in this representation.

[2] Some countries will be below and others above this baseline number.