-

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

-

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

-

15% Uncertainty: Greece, Europe and the tariff shockwave

15% Uncertainty: Greece, Europe and the tariff shockwave

-

Summit of transactions – Erdogan and Trump

Summit of transactions – Erdogan and Trump

-

Podcast - DETH and taxes: The only things certain in Greek politics

Podcast - DETH and taxes: The only things certain in Greek politics

-

How will Trump's tariffs affect Greece?

How will Trump's tariffs affect Greece?

Labour market developments in Greece during Covid-19

Every month, the Greek statistical agency ELSTAT publishes a helpful report on developments in the domestic labour market called the “Labour Force Survey.” The issue from February 11, 2021 presents data through November 2020 on employment, unemployment, and how many people in the WAP (the working-age population, 15-74 years) are inactive. These monthly reports have long time series attached to them which are also available from ELSTAT (in excel format).

Together with data on real GDP and real GDP growth, as well as the consumer price index, the developments in labour markets affect all families in a direct way. High unemployment is a loss for both the citizen affected and for society as a whole. Unemployed people have reduced financial resources to care for their families. Equally, their skills are not being used and may depreciate if unemployment is of long duration (over 12 months). Most tellingly, unemployment affects people psychologically. In short, there is good reason to pay attention to labour market developments and to use sound policies to keep unemployment as low as possible.

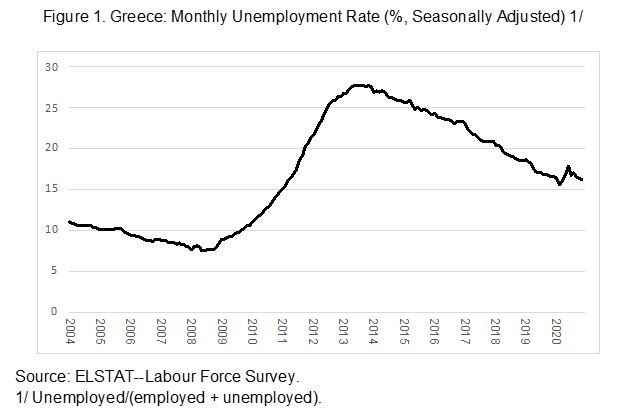

Let us look at unemployment in more detail. What do the numbers from ELSTAT tell us? Figure 1 provides the monthly (registered) unemployment rate. Unemployment varies with seasonal influences. The summer in Greece is tourist season and employment tends to rise and unemployment tends to drop. ELSTAT uses statistical techniques to take out this element of seasonal variation. Subsequently, the month-to-month figures can be compared on an equal basis to tell us what is happening “under the surface.” Looking at the chart some observations come to mind:

- The euro-crisis was devastating for Greece as unemployment reached 27.8 percent of the labour force in September 2013.

- Equally important, even during the boom times leading up to the euro-crisis, Greece’s unemployment rate never dipped below 7.5 percent. This is high in international comparison. It means that labour compared to average labour productivity is expensive in Greece.

- Much has changed during and after the euro-crisis in Greece. But the country needs further structural and labour market reforms, e.g., in areas such as vocational training, business licensing, wage policy and collective bargaining procedures.

- It is helpful to recall that harvesting the seeds of structural reform for a macroeconomy is time consuming, in particular for an economy that is recovering from a crisis as deep as Greece’s. It can take as much as one or even two decades for reforms to take full effect across sectors and labour market participants.

While the past decade was very difficult for Greece, the 2020s should be better, with economic recovery and employment consolidation. The challenge now is to see if government policy can assist to get unemployment down to, say, below seven percent, by the end of the 2020s? Since the peak of unemployment in 2013 during the euro-crisis, we have seen steady and good progress in declining unemployment. However, at 16.2 percent (November 2020) there is a considerable distance to go until single digits are reached.

The economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic have interrupted progress, with a new uptick in the unemployment rate. But compared to developments in previous years the magnitude of the increase has been moderate. Two factors chiefly account for this difference.

- The government introduced several support mechanisms to keep as many people in their jobs as possible.

- The unemployment rate is also being influenced by declining labour force participation (see next section).

A further characteristic of the labour market deserves attention. Macroeconomists argue that labour is a “lagged variable”. This means that if GDP declines (or increases), it takes a while before the full impact on labour markets can be seen. Thus, we advocate a sense of caution as regards the available data. While unemployment appears to have stabilized in Greece during 2020, there is a need for new growth to arrive before the unemployment rate resumes its previous decline in a sustainable way. This impetus also implies that it cannot be up to the government to prop up the labour market indefinitely. Other constituencies, such as unions, employers, and workers themselves, also need to contribute to bringing unemployment down.

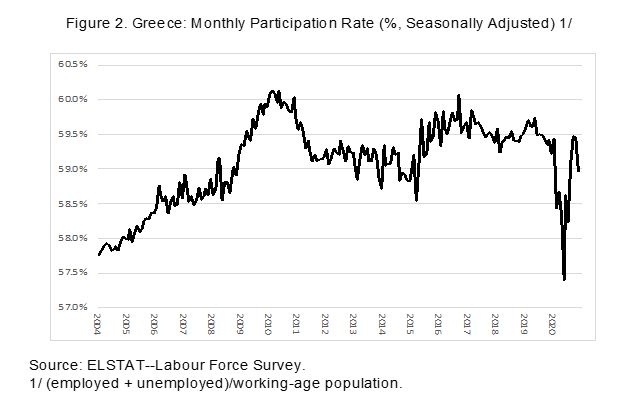

Participation. One cause of lower unemployment, besides new GDP growth, is that unemployed people may drop out of the labour market for recession-related reasons. They cannot find a job, are repeatedly turned down and then give up. This is known as the “discouraged worker effect.” We can get a hint of this effect by looking at participation and asking if the available total labour supply is rising or declining as a percent of the working-age population? ELSTAT once again provides the numbers as in Figure 2. What do we see?

· Participation, on trend, has been gradually increasing. This helps growth because more people within the working-age population are gainfully active in the labour market.

· At the onset of the euro-crisis in 2009, we even saw a temporary spurt of more people coming into the labour market as economic activity started to drop. This, too, is a known phenomenon. It says that when the principal earner becomes unemployed, often, other members of the family (or household) will seek employment to help support disposable income. This is called the “second-earner effect.” Whether the discouraged worker effect or the second earner effect wins out during an economic cycle is an empirical question.

· According to data by Eurostat and the OECD, overall participation in Greece is below the EU average. Formal work among women and the elderly is not yet as common as in other EU countries. Pro-active policies can encourage increased participation, including more flexibility and variety of employment contracts, the provision of more day-care, wage moderation, less early retirement, and guarding against excessive taxation of spouses.

· During the COVID-19 pandemic, participation at first plummeted as many people became discouraged and withdrew from the labour market. This initial development was partly overcome as participation recovered in the course of 2020. Yet, with the second wave of COVID-19, participation has started dropping again.

· Recessions do not usually lead to evenly distributed unemployment throughout the economy. They usually hit certain sectors harder. This is also being illustrated by the Covid-19 pandemic. But there is a new dimension to the characteristics of unemployment. What is unique about the pandemic is that it led to a “services-led recession” where services employment (e.g., in tourism, leisure and hospitality sectors) declined more aggressively in Greece and other European countries.

What do we learn from these observations? For now, we have two sources of lower unemployment that are not sustainable over time. Firstly, high government expenditure to help absorb the shock and, secondly, declining labour force participation. These two factors can change course in 2021. We emphasize that unemployment should primarily resume its previous decline on the basis of renewed GDP growth. Finally, any economic recovery is robust if it is supported by and contributes to a gradual increase in labour force participation. Higher participation rates imply that Greece can employ more citizens and create higher GDP levels. We can monitor the numbers as developments unfold through the excellent ELSTAT data sets.

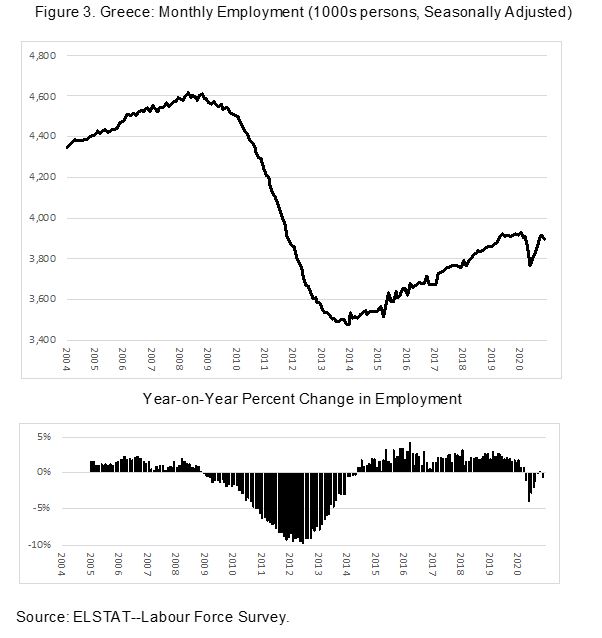

Let us now flip the question though: what about employment? Ultimately, GDP is produced by those who work, i.e., the gainfully employed population of Greece. More generally, employment growth itself is a good measure of progress in the economy. In the trend, real GDP (with a lead) and employment (with a lag) are closely correlated. ELSTAT once again provides the data as seen in Figure 3 above. Here are its main takeaways:

- The deep downturn in real GDP during the euro crisis is mirrored in the deep downturn in employment in Greece during the period 2009-2015. Employment is still 700,000 persons less than before the euro crisis. It will take a while before the full damage of the euro crisis can be unwound.

- Since January 2015, employment grew by an average of 1.5 percent year-on-year every month. That is a respectable result for Greece in international comparison. It indicates that the economy was trending in the right direction. It also underlines that efforts to stay this course should not be given up, even when an external shock - such as a pandemic - strikes. Steady progress is more durable than spectacular success stories. While the latter is politically more attractive, consistency over time is the name of the game.

The COVID-19 pandemic interrupted employment growth in Greece and in many other European countries. But that is only half the story. A closer look yields a surprising fact for Greece: employment growth stagnated since April-2019 and subsequently declined. The sobering observation includes the acknowledgement that this development had already set in well before COVID-19 emerged. This observation deserves closer scrutiny. More than the unemployment rate, the total level of employment - or its growth - tells us the story of how far the Greek labour market still has ahead of itself for a sustainable recovery.

Summary: In Greece, unemployment is coming down on trend, but progress has been interrupted by COVID. For now, and on the surface, the damage does not look as serious as during the euro crisis. Greek labour force participation was slowly improving over the years. Employment growth appears to have stagnated since April-2019, before COVID caused a further decline. Government transfers and European support programmes during the pandemic (e.g., SURE)[1] have sought to alleviate the impact on the labour market.

Recommendation: Government policies have supported the labour market thus far during COVID, but the levels of financial support provided are not sustainable in the long run. Labour markets still need reform to encourage participation, and wage demands should be moderate until unemployment falls to much lower levels. Tri-partite dialogue between the government, unions, and employer’s organizations has helped some countries to overcome recessions and high unemployment in a coordinated and cooperative manner (e.g., in The Netherlands, Belgium, Germany). Can it also be recommended for Greece? In some sectors it appears practical, e.g., taking place in the financial sector and telecommunications. In other sectors, e.g., shipping and ports, foreign investors have introduced new modes of compromise formula between job guarantees and wage flexibility.

The jury is still out. But the past crisis and current pandemic challenges have triggered a wholesale reset regarding active labour market policies, collective bargaining, compromise formation and the search for flexible solutions in Greece. Creating good (sustainable) jobs will require updating the toolbox of industrial, regional and innovation policies.

[1] The European instrument for temporary Support to mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency (SURE).