-

Podcast - Kaisariani photos: Why Greece’s past is present

Podcast - Kaisariani photos: Why Greece’s past is present

-

Is the Greek green transition running out of power?

Is the Greek green transition running out of power?

-

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

-

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

-

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

-

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

Quo vadis Germany? Sunday's elections leave many questions in need of answers

This election in Germany was the most unpredictable election cycle of the past 16 years. Contrary to the electoral campaigns during the era of Chancellor Angela Merkel, when the winner was already obvious before casting your ballot, this vote offered real alternatives, an open race to the wire and citizens who were mobilised to get out and vote. 60.4 million German citizens were eligible to vote for the 20th Bundestag. The German Parliament will subsequently elect the ninth chancellor of the Federal Republic. 2.8 million young men and women were first-time voters, corresponding to 4.6 percent of the electorate.

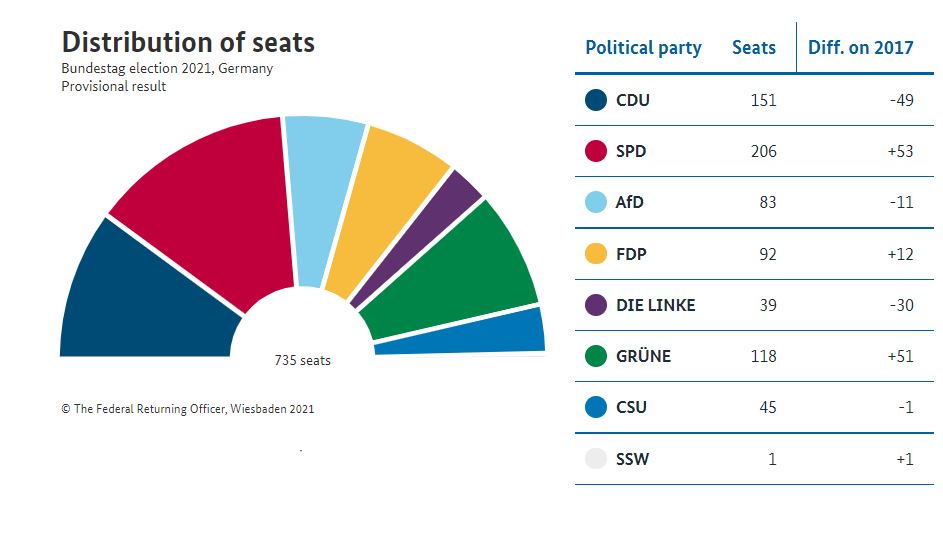

However, the elections were decided in the age category of citizens 60 years and older. This constituency corresponded to 38.3 percent of all eligible voters in Germany. Compared to four years ago voter participation increased 0.4 to 76.6 percent. Because of the Covid-19 pandemic, a record number of postal ballots (over 48 percent of the total) was cast in the weeks ahead of Sunday’s vote. A total of 24 parties were on the ballot. Eight of them will be represented in the new parliament in Berlin. The Bundestag now has 734 MPs against 709 MPs in 2017. This number sets a new record and is a matter of growing concern given its inflationary size.[1]

The electoral map of Germany is divided in strong gains for the Social Democrats in the west and north, the conservatives have their remaining strongholds in the south, the Green Party scores high marks in cities across the country and the AfD achieve the most votes in regions of former East Germany. The result offers numerous coalition alternatives, thereby promising extensive negotiations and complex compromises. Never in post-1945 German politics are so many different governing constellations possible. Whatever coalition is achieved – before Christmas – as many observers emphasised, it will have to be one which brings together parties that are characterised by major differences in the demography of their voters.

The new typography of German politics

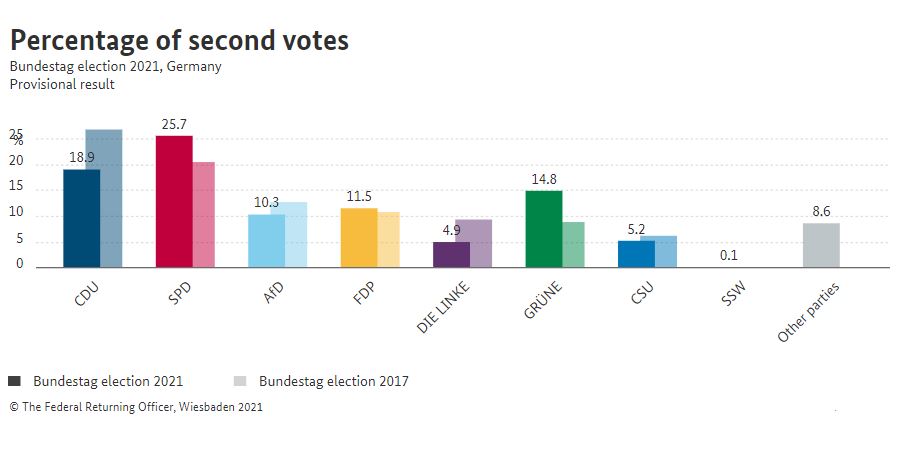

The Green Party received 14.8 percent of the vote. This level corresponded to a historical success for the ecologists. But many party representatives, members and voters appeared Sunday evening on television as if the Greens had lost the elections. In some ways they have indeed. This mixture of emotions had much to do with their choice of candidate for chancellor, the first time the Greens nominated a politician for Germany’s highest executive office.

The 40-year-old Annalena Baerbock has been a member of the Bundestag since 2013. Apart from working as a freelance journalist for a local newspaper and holding a trainee position in a British think-tank, she has never left the Green Party ecosystem for any other professional experience. Among voters she scored high marks in the categories ‘sympathy’ and ‘approachability’, but comparatively low grades in the key variables of ‘competence’ and ‘professional experience’ as a politician running for chancellor of Germany. Baerbock’s legacy will be defined by having failed to take advantage of a historical opportunity for the Green Party.

Squandering this opportunity because of personal mistakes (in her CV, her income declaration and plagiarism while advocating her book) cost Baerbock dearly at the polls. Credibility and competence are attributes in politics that are hard to attain and can be wasted within a moment. The Green Party which emphasises clean and transparent politics vis-à-vis the so-called “established” parties paid a high political price for these missteps. As Baerbock painfully learned, electoral campaigns are relentless public affairs, in particular under present-day conditions of permanent digital scrutiny.

The Greens also had to recognise that many citizens in Germany view climate change as a serious policy challenge and the Covid-19 pandemic as a devastating health crisis. But these concerns did not imply that most voters’ perceptions of politics are primarily based on pessimistic or even apocalyptic assumptions. Many citizens in Germany want to be prepared for the forthcoming changes with a mixture of regulatory clarity, social balance and the individual credibility of their decision makers. They did not associate these attributes with the leading candidate of the Green Party.

The right-wing extremists of the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) gained 10.3 percent, a decline of more than two percent compared to 2017. Despite the Covid-19 pandemic the AfD could not benefit from its crisis effects. But these elections also underlined that the AfD has a loyal voter base, corresponding to roughly five million voters. In Saxony the AfD repeated its success of four years ago and was the strongest party in the state. The AfD also scored first place in the region of Thuringia. The presence of a right-extremist party in the Bundestag is now a recurring fait accompli of German politics, accepted by the other parties who have all ruled out any cooperation with the AfD. The German media and most politicians have learned to deal differently with the AfD during the past four years. They do not anymore trigger ideological debates about what can or should not be said when AfD representatives attempt to move the political narrative towards their extremist objectives and rhetoric.

Olaf Scholz’s victory is a personal triumph for a social democratic politician who has served in different ministerial positions and was mayor of Hamburg before focusing on politics in Berlin. After almost two decades the SPD is once again the strongest party in a general election, having won 25.7 percent, a gain of more than five percent against 2017. Scholz’ electoral campaign was characterised by strict message coherence, organisational discipline and a measured tone when addressing voters. His overall performance during the past months on TV and while canvassing voters earned him the nickname ‘red Buddha’.

Scholz owns a significant part of his and the SPD’s electoral success to the fact that he managed to come across for many voters as a male version of Angela Μerkel. His imitation talents went as far as deliberately being photographed with the same signature hand pose as his former boss in the chancellery. From the start of campaigning Mr. Scholz focused a key part of his strategy on citizens who had previously voted for Ms. Merkel. His calculation, which proved correct, was based on the assumption that the candidate who can catch the highest share of her loyal voters would ultimately win the elections. The German electorate includes a sizeable number of older citizens who tended towards the conservative CDU while Merkel held the executive office in Berlin. But they were willing to consider changing their party preference once it became clear that chancellor Merkel would not run again for office.

The victory of Olaf Scholz and the success of the SPD is also due to their luck of having faced two rather unconvincing candidates for chancellor from the Green Party and the conservative Christian Democrats (CDU). Scholz started to rise in the polls precisely at a time when his two opponents had sufficiently embarrassed themselves on various private and political fronts. The weaknesses of his two rivals contributed to highlight the strengths of the candidate from the SPD. Avoid unforced errors, stick to the script and repeat your key messages in a sober tone. This political chemistry made Scholz appear reliable, predictable and in the eyes of many citizens credible. The renaissance of the SPD was particularly significant in the states of former East Germany, among citizens aged 60 years and more as well as in the largest cities of the country (Berlin, Frankfurt, Hamburg, Munich).

The CDU in the post-Merkel era recorded a historical crash at the hands of the electorate. The conservatives are now a second-place 20 percent plus party. They lost more than 8 percent compared to the elections in 2017. In issues traditionally associated with the CDU, e.g. the economy, domestic security and the health sector the conservative party lost credibility among older voters and declined dramatically in policy competence. The CDU is experiencing the same erosion of their electoral base as the social democrats did more than a decade ago. As neither the SPD nor the CDU came close to 30 percent, we are witnessing in real time the end of the traditional ecosystem of two catch-all parties in German politics. The new normal will be three-party coalitions in order to attain a working majority in parliament. The composition of such coalitions will vary across the political landscape of Germany.

Armin Laschet had to learn the hard way that many citizens who voted for the CDU because of Ms. Merkel during past elections could not muster enough enthusiasm for the conservative chancellor candidate from the same party. His late nomination in April of this year after a bitter competition with his Bavarian counterpart in the sister party CSU cost Laschet dearly. Never was the CDU able to unite their candidate and its electoral programme with the requirements of a long campaign. A focused campaign strategy of the conservatives lacked time, coherence and organisation. Laschet’s profile, what he stands for never became clear throughout his travels up and down Germany. The loss of 53 seats in the Bundestag will lead to intense power battles over the future direction and personnel of the conservative alliance between CDU and CSU.

The coalition options

The 16 years of chancellor Merkel come to an end with a new party ecosystem in Germany. Eight parties now crowd the Bundestag, no party came close to 30 percent of the vote, and new three-party government constellations characterise the typography of German politics. No party is politically prepared to deal with this unprecedented result. Whatever the ultimate outcome of complex and contentious coalition negotiations in the coming weeks, the results of the elections on September 26, 2021 mark a watershed moment for German politics. The 16 years of Angela Merkel’s residency in Berlin’s ‘washing machine’ - as the building housing the chancellor is called in colloquial speech - mark the end of an era. It appears most likely that no future German chancellor will again hold office for such a long and uninterrupted period of time.

Germany has now arrived in the post-catch-all party system. In that respect the country’s party political architecture now resembles most other European countries. Moreover, two-party coalitions at the federal level are increasingly mathematically impossible and politically out of date. The chancellery in Berlin will feature a novel three-party coalition, the precise make-up of which remains unclear at the time of writing. An unprecedented number of coalition options are available to the negotiators. But what may appear numerically feasible, is not equally politically viable.

The continuation of the unpopular ‘Grand Coalition’ (SPD and CDU) is still mathematically possible, but politically exhausted. Even if such a coalition would now be led by a social democratic chancellor, the rank and file of both parties is opposed to it and there is no momentum for this red-black arrangement in German society. Ms. Merkel epitomised such a coalition, and her resignation is a matter of time until and when a new governing configuration is formed. The target date is before Christmas.

The ‘traffic-light coalition’ (red for the SPD, yellow for the Liberal Party (FDP) and green for the Green Party) is the most preferred option for the Social Democrats and the Greens. But issues ranging from tax policy, minimum wage increases, pension reform and environmental regulations for the car industry separate both the SPD and the Greens from the third prospective partner, the FDP. The ‘traffic light coalition’ (in German Ampelkoalition) currently exists at the state level in Rheinland-Palatinate and previously governed in the state of Brandenburg and the city state of Bremen. It has never been attempted at the federal level.

If the political differences of the previous two coalition options prove to be insurmountable, then the so-called ‘Jamaica coalition’ becomes an option. This CDU (black), Green and FDP (yellow) configuration was already attempted at the federal level back in 2017. It failed to materialise after months of negotiations because the FDP pulled out at the last moment. The unexpected move ultimately led to a renewed ‘Grand Coalition’ between the CDU and the SPD with Angela Merkel as chancellor. The possibility of a Jamaica coalition cannot be ruled out even if it excludes the strongest party that won the elections, the SPD. But such a colourful coalition would stand on thin ice. This could well be all the more a reason to attempt forming everybody’s second-best coalition option in Germany. Much is in flux in German politics. The voters have handed their representatives a challenging task. The Merkel era ends with the agonising question: Qua vadis Germany?

*Jens Bastian is senior policy advisor at ELIAMEP.

[1] The House of Commons in the UK has 650 members. The Assemblée Nationale in France counts 577 MPs. The Camera dei Deputati in Italy has 630 MPs while the House of Representatives in the U.S. has 435 members.