-

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

-

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

-

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

-

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

-

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

-

15% Uncertainty: Greece, Europe and the tariff shockwave

15% Uncertainty: Greece, Europe and the tariff shockwave

The arduous road of privatisation in Greece

This week two developments at the Hellenic Republic Asset Development Fund (HRADF) made headline news. First, the Greek privatisation agency confirmed its medium-term revenue targets. The HRADF’s chief executive officer, Paschalis Bouchoris, in charge since August of this year, argued that TAIPED (as it is known by its Greek acronym) can reach the revenue target of 9.6 billion euros by the end of 2016.

Bouchoris’ three predecessors have constantly had to revise downward the HRADF’s revenue projections. Thus, the new CEO’s optimistic outlook has to be viewed with a sense of caution. All the more given the fact that only one day after Bouchoris’ revenue target confirmation TAIPED’s executive director, Andreas Taprantzis, announced his resignation.

Taprantzis held this position for three years. He was a rare example of continuity at the senior management level of the Greek privatisation agency. Since its inception in mid-2011, HRADF has had a constant turnover in the position of chairperson and/or chief executive officer.

What does this coming and going tell us about the state of play in the Greek privatisation process? What should potential foreign investors make of the fact that they have to adjust their senior contact list of TAIPED management on a yearly basis? Why is the privatisation process fraught with political controversies, a lack of public support in large parts of Greek society and subject to ever-increasing administrative delays and judicial objections?

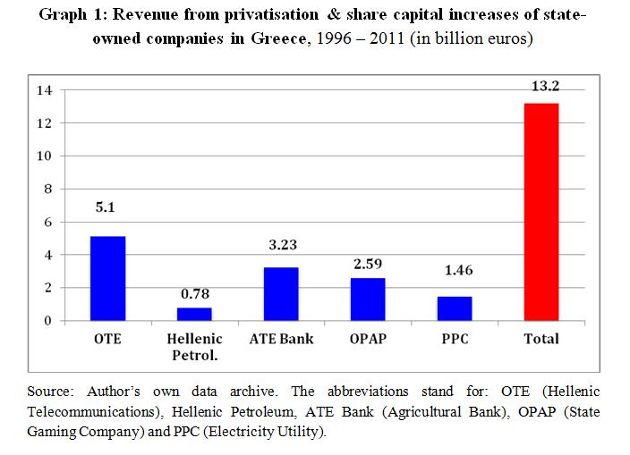

As the accompanying graph illustrates, a look back at the recent history of privatisation in Greece yields some interesting insights and helps inform us about the magnitude of the task at hand. The graph displays a selected number of public utilities and state-owned enterprises that were gradually listed on the Athens Stock Exchange through IPOs and subsequent share capital increases over the course of the past 20 years.

The total revenue generated during the period 1996-2011 amounted to roughly 13.2 billion euros. Such a volume reflected a time when piecemeal Greek asset sales could fetch comparatively high prices and under completely different economic circumstances than the ones which prevail today. The single largest and most consistent revenue stream from the combination of privatisation and multiple share capital increases originated from the telecommunications sector, i.e. OTE.

Since the establishment of HRADF in 2011 the Greek privatisation strategy has suffered from a number of deficits that have impacted on its operational capacity, internal cohesion and determination to deliver based on its own objectives.

When undertaking such an unprecedented, ambitious and politically charged privatisation process, as is the case in Greece since 2011, setting revenue targets is a risk-prone enterprise. Instead, defining the programme’s rational, the specific policy objectives and national strategies that are to be achieved in sectors such as airports, motorways, ports and energy prior to the privatisation process are far more important than the amount of revenue to be generated.

The public debate around these rationales and objectives, the institutional preconditions necessary and the political support that must frame such an inquiry have never really taken place in Greece since HRADF started to operate.

In other words, revenues from privatisation are an important benchmark. This income was used by the troika of international creditors as an evaluation tool in the quarterly compliance reports. But the inclusion of privatisation income in the HRADF’s balance sheet should only be one element of a much broader assessment. The questions searching for answers concern inter alia the following aspects:

· To what degree is a specific asset disposal linked with commitments by the future investor to safeguard and/or create an agreed number of jobs? What kind of vocational training objectives can be included in the sales contract?

· Leading away from an exclusive focus on revenue levels to be achieved from the sale of a state-controlled company, the ratio of follow-up investments attracted for every euro of privatisation income is equally relevant

· Selling off infrastructure assets includes the need to communicate with the domestic audience and through road shows with prospective international investors. Greece’s track record in salami-style privatisation steps during the period 1996 - 2011 had not been a confidence inspiring policy for foreign investors seeking management control in companies they were prepared to invest in.

· The amount of regulatory and institutional preparation that was necessary along with the establishment of HRADF would have suggested caution in terms of the management of expectations. But modesty in public pronouncements about the programme’s operational capacity are a work in progress. Statements such as Greece being able to become “an El Dorado for investors” – as the then chair of HRADF Takis Athanasopoulos said during an interview with the Financial Times in September 2012 - may have done more harm than intended. Labour unions, coalition and opposition MPs as well as civil servants hesitant about or outright opposed to the privatisation programme seized on such bonanza-like pronouncements.

For any privatisation programme to gain traction and credibility over time it needs astute leadership and management continuity in the top positions. Since its establishment in mid-2011 HRADF has had five presidents and three chief executives. These resignations have neither helped the process of anchoring the privatisation programme in Greek society, nor have they been a confidence builder in the merits of the strategy among potential foreign investors.

Equally, constant personnel changes in the top echelons of HRADF adversely impact on its capacity to execute strategies and close pending privatisation agreements. This constant reshuffling of top management has not aided the fund’s working arrangements with the troika, leading to delays in portfolio management, pre-privatisation asset re-allocation and adhering to agreed timetables.

Until a sell-off project can fully mature in Greece a host of other pre- and post-privatisation issues need to be clarified. This includes the creation of permits, the confirmation of licences, the approval of their regulation by Parliament, the consultation of the Council of State and in many cases the Commission in Brussels as regards outstanding infringement cases and repayment of subsidies.

Moreover, every asset disposal that includes physical infrastructure such as buildings, surrounded by parking space, open communal areas and proximity to the coastline as well as beach resorts requires a multi-phased process of environmental assessment and special town planning development procedures.

This process not only complicates the entire procedure in terms of time, administrative and legal complexities, but also involves numerous institutional actors and agencies that do not necessarily share the same view on the specific privatisation target, the sales contract or the type of investor chosen.

Finally, the legal mandate of the HRADF defines the Fund as a sales manager. But the empirical reality of the privatisation process during the past three years in Greece strongly suggests that its role is much broader. The administrative and institutional deficits also oblige the fund to serve, for lack of a better alternative, as an asset manager.

These very practical obstacles, administrative hurdles, legal impediments and policy coordination demands make the conclusion of a privatisation project in Greece a gargantuan challenge. But they also underline what it takes to implement such an asset disposal programme against the backdrop of distressed markets and adverse economic conditions. Bringing the public on board remains a work in progress and requires patience as well as perseverance.

*Jens Bastian is an independent economic consultant and investment analyst for southeast Europe. From 2011 to 2013 he was a member of the European Commission Task Force for Greece in Athens. He is a regular contributor to The Agora section of Macropolis. Follow Jens on Twitter: @Jens_Bastian

1 Comment(s)

-

Posted by:

Imho currently the task is not "gargantuan" but simply impossible for the following reasons:

a) The legal and organizational preconditions only exist in such relatively simple cases like selling a functioning maritime port to Chinese investors, who are prepared to take high risk in exchange for getting it's foot in European industries.

b) The risk of political instability in Greece is much too high for investors searching good returns without too much risk.

c) Selling is hard to impossible if the seller is in a weak position. And selling at low clearance prices does not remedy the problem!