-

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

Podcast - Walking a tightrope: Greece’s geopolitical balancing act

-

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

From nice story to pulped fiction: Carney delivers reality check on rules-based order

-

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

Record bonds, rising bills: Greece’s economic paradox

-

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

Podcast - Tax cuts and balancing acts: Greece's 2026 budget

-

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

Podcast - Main character energy: Greece vies for leading fossil fuel role

-

15% Uncertainty: Greece, Europe and the tariff shockwave

15% Uncertainty: Greece, Europe and the tariff shockwave

Our most popular stories in 2014

These are the stories that were read most in each of our four sections (Politics, economy, society and The Agora) during 2014. We thank you for your support and look forward to providing more top quality analysis in 2015. We wish you all a healthy and happy New Year.

We remind you that we offer free 30-day access to MacroPolis to all readers. Just sign up here. No financial details are required. The Agora, our forum for debate on political and economic developments in Greece and beyond will continue to be free in 2015.

Politics - 11/02/2014

Supreme Court ruling casts doubt over property tax revenues

A Council of State ruling in January looks to have blown a 500-million-euro hole in the government’s fiscal plans. Now a Supreme Court verdict is threatening to create an even bigger shortfall in Greece’s public finances.

Last month’s judgement is likely to lead to the coalition repaying about 500 million euros it cut from salaries in the armed forces and police. The details will only be known when the verdict is published, which could take a few weeks longer. The Supreme Court ruling, which was made public on Friday, deems that the emergency property tax introduced in 2011 and levied through electricity bills was unconstitutional.

The verdict applies to the tax for 2011 and 2012, not last year when it was incorporated into a wider property levy. During the two years in question, the government is estimated to have collected more than 2.5 billion euros from Greek taxpayers. The tax was introduced by the then PASOK government, with Evangelos Venizelos as finance minister, as a last-ditch attempt to meet the troika’s fiscal targets despite concerns about whether it would stand up in court.

However, we are still some way from the government having to repay to taxpayers the 2.5 billion euros or so, which is equivalent to roughly 1.5 percent of GDP – a move that would obviously derail its attempt to produce a primary surplus and meet the troika’s fiscal targets.

The verdict was reached by the Supreme Court’s fourth section, not the plenary. Three out of the five judges deemed that the tax was unconstitutional because it taxed people based on the size of their property, which was not necessarily an indication of their wealth, and not on their income. However, because two of the judges disagreed with this interpretation, the matter is now being referred to the Supreme Court’s plenary.

There is no fixed date for when the plenary will convene but it is expected to happen within the next three months. If the judges reject the fourth section’s verdict, the appeal against the tax, which began with a 2012 first instance court ruling, will have reached its end and the government will breathe a sigh of relief.

If the plenary agrees with the fourth section’s ruling then things get even more complicated. The Supreme Court’s decision would clash with a ruling from the Council of State, which last year deemed the emergency tax to be legal but said it was unconstitutional to cut off taxpayers’ electricity if they did not pay.

The only way of resolving this legal contradiction would be for the Supreme Special Court to convene, which does not happen often. Its 11 members would have to deliver a final opinion on whether the tax is in line with Greece’s constitution or is illegal. If they choose the latter, it still will not mean an immediate payout for the government. Instead, armed with the court’s decision, each taxpayer will have to make a separate appeal for the money they paid in 2011 and 2012 to be returned.

Whatever the outcome, the hasty and improvised manner in which Greek governments have taken decisions to meet the various targets they were set is being exposed. With other civil servant groups already appealing cuts to their wages, the government is likely to have many nervous days ahead as it keeps an eye out for court verdicts.

-----------------------------------------------------------------

Economy - 30/11/2013

Has internal devaluation really helped Greek exports?

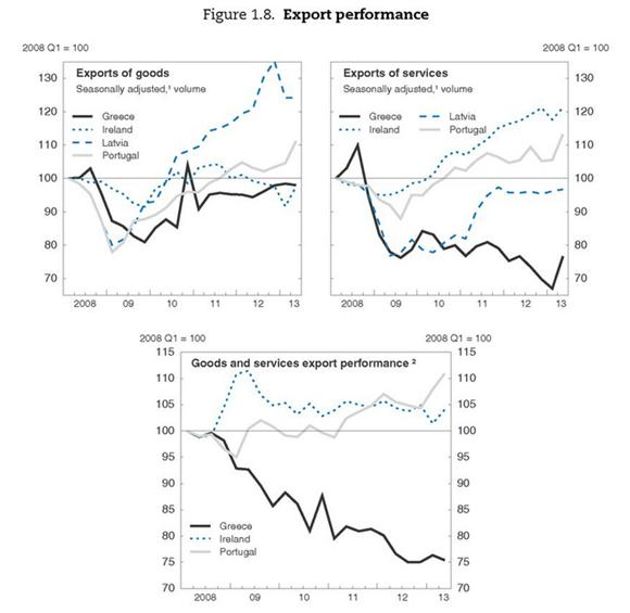

The performance of Greece’s exports has been one of the main disappointments of the troika-led program. One of the pillars of Greece’s adjustment was meant to be internal devaluation, which through a number of reforms that would stimulate growth, absorb the collapse of domestic demand and re-direct production and capital to tradable goods.

In the report it handed to the Greek government earlier this week, the OECD takes a detailed look at the performance of Greek exports and highlights a number of factors that are holding back their growth. Many of these elements are related to the policies pursued by the troika and Greek governments since the crisis erupted.

The Greek share in exports markets has been steadily declining since 2008 and the reforms implemented since 2010 have not had much of an impact in averting this trend. The decline in exports over the last three years is led by the exports of services. For instance, maritime transport exports, where Greece is known to have a competitive advantage have been weak due to the slow pace of global trade and oversupply in the shipping sector since 2010, as the OECD highlights.

Furthermore, tourism revenues were badly damaged by the political uncertainty and repeated statements by European politicians in 2012 putting the country’s euro future in doubt.

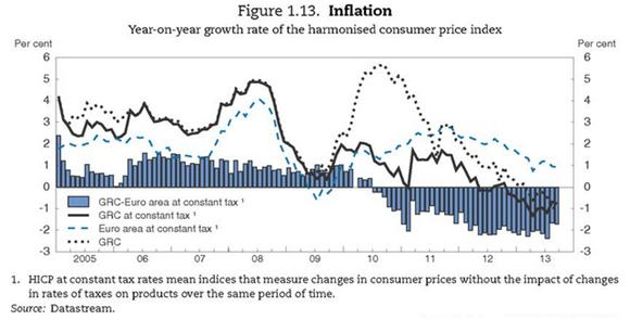

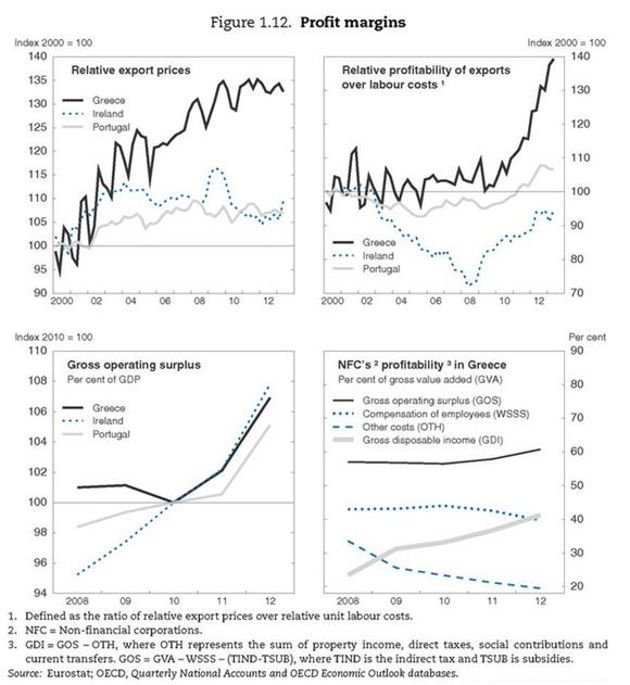

The OECD report stresses that despite the fact the sharp rise in unemployment and the deregulation of the labour market, which has managed to erase in just three years all the labour cost competitiveness lost between 2000-2009, prices have not followed the same path.

According to the Paris-based organisation, price competiveness is of acute importance for Greece as its exports are concentrated at low-tech products. Greece’s high-tech exports account for only 28 percent of exports when the same figure for Portugal is 40 percent and the EU and OECD average is 50 percent.

The lack of price adjustment compared to labour costs partly reflects higher indirect taxes and public service charges as a result of the fiscal consolidation effort that Greece is undertaking. The OECD finds that indirect tax increases pushed the cumulative effect of consumer price inflation by 6 ¼ percentage points between 2010 and 2012. If public service tariffs are also included the cumulative price push up is 9 ½ percentage points.

The lag in adjustment of prices is also a product of the nature of the Greek economy, which is dominated by small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). The report finds that 60 percent of the turnover is in the hands of SMEs, compared to 40 percent for the European average, and Greek SMEs are half the size of the European SMEs. As such, the weight of fixed costs that has been growing in contract to the labour costs since the crisis started is affecting the capacity of small firms to adjust their profit margins as opposed to big firms that have economies of scale.

Given that internal devaluations do not have the automatic effect of reducing relative prices that favour the tradable and exports sectors as a traditional devaluation would do, the OECD stresses that well-functioning products markets are essential for labour cost adjustments to also be reflected in prices.

The OECD stresses that even in sectors that have been liberalised they are forced to operate in very unfavourable macroeconomic conditions. Specifically, the liquidity drain in the economy is impeding the entry of new players that will apply competitive pressures and push prices down.

Additionally, non-labour related costs are on the rise resulting from difficult or expensive access to bank credit, supplier cutback of credit, long waiting times for VAT refunds from the state and delays in payments by customers, in many cases the state itself.

The report concludes that price adjustments are gradually being felt with the decline in prices being more pronounced in services exports sectors where labour costs have a higher share, with prices of tourism services having fallen sharply despite the indirect tax rises.

Overall, the OECD’s findings underline the complexities and challenges of improving competitiveness and performance of exports. They also suggest that the approach adopted during the Greek program, which has focused largely on costs and not so much on the ease of doing business, have been too one-sided and may in some cases been counter-productive.

-----------------------------------------------------------------

Society - 04/08/2014

Greeks living in smaller, older, poorer quality homes during crisis, BoG study shows

A study published in the latest Bank of Greece (BoG) economic bulletin highlighted the deterioration in Greek households’ living and income conditions during the years of crisis (2008-2012).

On the living conditions, the study showed a large increase of households living in houses built before 1960, with the respective share to total houses increasing to 12.3 percent in 2012 from 9.9 percent in 2008.

It is estimated that 1 million houses in Greece were built after 2000 but only 10 percent is inhabited.

The evolution of houses by type showed that the annual growth rate of detached houses eased by 0.2 percent in 2008-2012, apartments grew by 1 percent, while other type posted a double-digit annual growth of 14.4 percent.

Since this specific category includes huts, shacks booths and shops, the BoG study concludes that an increasing number of families are using homes of extremely low quality, while a number of households are living in their shops.

On home ownership, the study displayed that more than 60 percent of households (2.55 million) are homeowners without any mortgage. This is the highest reading among EU countries in 2012, well above the EU and eurozone average of 43.2 and 38.4 percent respectively and only comparable with that of Italy at 58 percent.

The number of own dwellings with mortgages showed a rise of 12.5 percent in 2008-2012. Taking into account that housing loans have been reduced over this period, the BoG study concludes that the positive growth rate concerns old housing loans for which either the payment has been extended or for houses that have been protected against foreclosure.

In addition, there was a growth of 10.2 percent between 2008 and 2012 in the number of homes being rented by owners to others for no fee.

Another interesting finding relates to the area of inhabited houses. Those below 40 square meters (sqm) showed an annual growth rate of 7.3 percent, whilst the respective rate for inhabited houses larger than 100 sqm posted an annual drop of 3.6 percent.

In terms of the number of rooms per person, Greece has the lowest ranking at 1.2, followed by Portugal and Italy, while the respective EU average stood at 1.7 for 2012.

The breakdown of households per income during 2008-2012 showed the dramatic burden on household disposable income from recession and austerity measures.

In 2008, households with monthly income above 3,500 euros enjoyed the highest share at 22.3 percent of total. This almost halved to 12.2 percent in 2012.

Similarly, the next bracket including households with monthly income between 2,800 and 3,500 euros showed a drop of its share from 12.8 percent in 2008 to 8.4 percent in 2012.

In contrast, the lowest share (4.8 percent) in 2008 was registered from households with income less than 750 euros. This more than doubled to 10.6 percent in 2012. The next lowest bracket (751 – 1,100 euros) showed its share rising to 15.4 percent in 2012 from 10.7 percent in 2008.

The BoG study also showed that the average disposable income in Greece fell by 15.8 percent in 2008-2012 to 10,676 euros. Over the same period, the EU-27 and eurozone average posted an increase of 7.1 and 4.3 percent respectively. In addition, the discount of Greece’s figure to the eurozone average widened from 32.8 percent in 2008 to 45.7 percent in 2012.

The study showed that the Greek population decreased, easing by an annual rate of -0.3 percent in 2008-2012 compared to an annual growth of 0.3 percent in the preceding 5 years. In the EU, both rates were positive at 0.2 and 0.4 percent respectively.

In absolute figures, the Greek population reached 11.06 million in 2012 from 11.19 million in 2008.

In Greece, the share of older people (with age higher than 65 years) to the total population rose to 20.1 percent in 2012 from 18.7 percent in 2008, remaining at the high end among EU countries. The EU average showed smaller increase to 18.2 percent in 2012 from 17.3 percent in 2008.

The decline in the size of the Greek population came despite Greece being the third highest in the EU between 2008 and 2012 when it came to the entry of migrants, with 44.8 immigrants per 1,000 inhabitants. This is explained by the fact that over the same period, Greece was ranked first in terms of exit of migrants with 46 immigrants exiting the country per 1,000 inhabitants.

The study showed that Greece and Portugal were the only countries that showed a higher number of immigrants exiting rather than entering the country. The key reason for non-Greek migrants exiting the country was the drop in the construction activity since more than half were employed in this sector.

-----------------------------------------------------------------

The Agora - 12/03/2014

The Greek crisis we don't see - By Nick Malkoutzis

The economic impact of the Greek crisis has been well publicised. A recession that began in 2008 has led to GDP contracting by a quarter, while unemployment has risen above 27 percent. Greece’s fiscal consolidation effort has also received much attention. A general government deficit of 15.6 percent in 2009 was transformed into a small surplus in 2013 – one of the sharpest adjustments the world has ever seen.

What sometimes goes unnoticed, though, is the effect these developments are having on people and their daily lives. The social cost of the crisis is often hidden from visitors and casual observers. It lurks behind the sight of apparently relaxed Athenians sipping coffee in the sunshine or seemingly carefree islanders clinking together their second or third glasses of ouzo.

In fact if one excludes some parts of Athens and other big cities, the signs of the crisis are not always that visible. Perhaps the frequent media images of protesting, rioting and poverty mean that these are the pictures we store in our brains and the standard by which we measure whether people are going through turmoil or not.

There are a number of reasons why the signs of the crisis are elusive. Perhaps the overriding one is that the social impact can rarely be seen on the street, on the beach, in cafes or in restaurants. It is most evident in places that are out of our direct view: Living rooms, offices, factories, hospitals and in the deepest, darkest recesses of people’s minds. In these places, the crisis is very real and very disturbing.

Recession

Greece’s recession, which began in the second half of 2008, has put enormous strain on Greek society. An increasing amount of Greeks are finding themselves socially excluded.

According to the latest figures from the Hellenic Statistical Authority (ELSTAT), 34.6 percent of the population was considered to be living at risk of poverty or social exclusion in 2012. This is the highest proportion in the European Union. This figure stood at 27.7 percent in 2010, when the crisis broke out.

According to ELSTAT, 19.5 percent of Greeks are severely materially deprived. This is by far the highest rate in the eurozone, compared, for example, to 8.6 percent in Portugal, 5.8 percent in Spain and 2.3 percent in the Netherlands.

Greek household disposable income has dropped by more than 30 percent since the crisis began. This has contributed to even the basics becoming a challenge for a lot of Greek families.

A poll carried out for the Small Enterprises’ Institute of the Hellenic Confederation of Professionals, Craftsmen & Merchants (IME-GSEVEE), indicates that about a third of households (34.8 percent) said that they are behind in their payments to the state, banks, social security funds or public utilities due to money shortages. More than 40 percent (41.7) said that they would not be able to meet their commitments for this year.

The Public Power Corporation is disconnecting around 30,000 homes and businesses a month due to unpaid bills.

Unemployment

Unemployment is the biggest concern in Greece at the moment. Over the past four years the number of unemployed Greeks has risen by about 160 percent. As a result, around 3.5 million employed people have to support more than 4.7 million unemployed and inactive. There isn’t an economy or labour force in the world that could sustain this for much time, certainly not without the strains on its society showing.

Unemployment plays a big factor in placing a large number of Greeks at risk of social exclusion (52 percent of men without jobs are at risk of poverty) but even those with jobs are not always secure. More than 27 percent of Greeks with part time work are considered to be at risk of poverty, while the same applies for 13.4 percent of those with full time jobs.

It is also worth considering that roughly one in four Greek workers do not receive their wages on time, some waiting several months to get paid.

For those without work, the lack of comprehensive welfare coverage is a major problem. The jobless only receive monthly benefits of 360 euros for the first 12 months they are not working. As a result, only 15 percent of Greece’s almost 1.4 million unemployed are currently receiving financial assistance from the state.

Also, until now, there has been no safety net for the self-employed, who make up about 25 percent of the local work force. The government has proposed a scheme that will see the self-employed receive 360 euros a month for up to 9 months. To receive unemployment benefit for that long, someone will need 15 years worth of social security credits.

Spending cuts

Public spending cuts have also contributed to more Greeks being left exposed to the effects of the crisis.

Without social transfers, almost half of Greece's population would be living at risk of poverty. However, social spending has been cut considerably over the last few years. Social transfers were reduced by 6.8 percent between 2012 and 2013. They are due to be cut from about 17 billion euros in 2013 to just under 14 billion this year – a reduction of more than 18 percent.

Apart from having limited access to unemployment benefits, Greeks are also being cut off from free or subsidized healthcare which is available to most unemployed Greeks for only two years. In 2011, Greece spent 11.6 percent of its budget on healthcare, compared to an OECD average of 14.5 percent. Per capita healthcare spending was reduced by 11.1 percent between 2009 and 2011 – the largest cut among OECD member states.

During this time, the number of HIV cases, instances of tuberculosis and cases of stillbirths have all risen considerably. Demand for mental health services has increased by more than 100 percent. According to a study by the University of Athens, 12.3 percent of Greeks are suffering from clinical depression at the moment, compared to just 3.3 percent in 2008.

A recent report by researchers from Oxford and Cambridge universities, which was published in the British medical magazine The Lancet, accused the Greek government and its lenders of being in “denial” about the impact that austerity is having on healthcare.

Family and charity

The lack of work and the scaling back of social welfare mean that often the main safety net available to Greeks in difficulty is provided by family.

The IME-GSEVEE survey suggests that for 48.6 percent of families, pensions are the main source of income. The average basic pension in Greece is just under 700 euros per month. It has been reduced by about 25% since 2010 and is due to be halved over the next few years.

Donations and services offered by volunteers have also become vital in helping Greeks who have been pushed to the margins of society.

The Municipality of Athens, for instance, feeds roughly 1,400 people a day, while doctors providing their services for free administer donated medicines to more than 4,000 patients a year who visit them at a volunteer clinic in Elliniko, southern Athens.

There are numerous other individuals and groups running programmes to assist fellow citizens. The safety net that has been unfurled by family members, volunteers and charities is one of the reasons that on the surface Greek society’s difficulties don’t seem too dramatic.

In fact, the awakening of this spirit of solidarity has been a ray of hope amid the social desolation being caused by the Greek crisis. As encouraging as this is though, we should not kid ourselves into thinking it’s more than a bright spot on a social landscape that is much darker than should be acceptable for a developed European country.